W. B. Scott

1887

|

Georges Cuvier was one of the first to propose that Classical and medieval references to the discovery of giants' bones were mistaken identifications of the fossils of extinct elephants and other prehistoric mammals. Later writers expanded on his insight, offering new and interesting details about the fossil origins of fabulous beings from myth and legend.

Much cited by never reprinted, paleontologist William Berryman Scott's (1858-1947) "American Elephant Myths" from Scribner's magazine (April 1887) is one of the most famous attempts to link myths and legends to the influence of fossil remains of prehistoric creatures, specifically attempting to trace the influence of the mammoth and the mastodon on Native American lore. Although portions of his analysis are quite wrong, especially the fanciful reconstruction of Maya art as "elephants" (an unintentional boon to alternative history speculators like Graham Hancock), in the main Scott provided a solid foundation for understanding how Native Americans imagined fossils. |

American Elephant Myths

Although it is now a well-known fact that the earth was formerly inhabited by many races of animals which have entirely disappeared, it is only within the last century that the notion of extinct animals has been accepted even by scientific men. The attempts which before that were made to explain the presence of huge bones and teeth in the soil of Europe, America, and Northern Asia, seem very amusing when read by the light of our present knowledge. The range of conjecture was, however, a limited one, and it is interesting to observe the strong likeness of the theories constructed by the sages of Greece and Rome, India and China, mediaeval and modern Europe, to the myths and traditions found among the savages of Siberia and the two Americas. The giants, dragons, and griffins and other monsters which abound in the folk-lore of all nations, may often be distinctly traced to conjectures as to the bones of extinct elephants.

|

The attention of Greek and Roman naturalists was early drawn to the tusks and bones of fossil elephants, which are so abundant in the soil of Europe, from which they constructed vast giants. Thus we have the bones of Orestes dug up at Tegea by the Spartans, the skeleton of Antaeus in Mauritania, that of Ajax in Asia Minor, a giant forty-six cubits high found in Crete, and a host of others. Herodotus, Strabo, Pliny, and Philostratus give much space to descriptions of these monsters. Even the Christian fathers did not disdain to make use of these tales. St. Augustine, in proof of the greater stature of the Antediluvians, says: "I myself, along with some others, saw on the shore at Utica a man's molar tooth of such a size that, if it were cut down into teeth such as we have, a hundred, I fancy, could have been made out of it."

Mediaeval literature abounds in giants. A monstrous one was found in England in 1171; the bones of Polyphemus were dug up in Sicily, and from time to time such remains were discovered all over Europe, and as the finders always knew the particular individual to whom the bones belonged, many duly labelled were hung up in the churches. Thus an elephant's shoulder-blade did duty for St. Christopher in a Venetian church, and the bones of Teutobocchus, king of the Teutons (now known to be a mastodon's skeleton), were, according to Mazuya, found in a brick tomb bearing the inscription, "Teutobocchus rex." Felix Plater's famous giant, which still figures in the arms of Lucerne, arose from some elephant remains found in 1577. A large elephant's tooth was sent from Constantinople to Vienna and offered to the emperor for two thousand thalers. The discoverers pretended to have found it in a subterranean chamber at Jerusalem which bore the Chaldean inscription: "Here lies the giant Og." But this was too great a strain on the faith of a very credulous age, and the emperor declined to purchase because, as Lambecius quaintly says, "The whole thing looked very like an imposition." |

Mediaeval literature abounds in giants. A monstrous one was found in England in 1171; the bones of Polyphemus were dug up in Sicily, and from time to time such remains were discovered all over Europe, and as the finders always knew the particular individual to whom the bones belonged, many duly labelled were hung up in the churches. Thus an elephant's shoulder-blade did duty for St. Christopher in a Venetian church, and the bones of Teutobocchus, king of the Teutons (now known to be a mastodon's skeleton), were, according to Mazuya, found in a brick tomb bearing the inscription, "Teutobocchus rex." Felix Plater's famous giant, which still figures in the arms of Lucerne, arose from some elephant remains found in 1577. A large elephant's tooth was sent from Constantinople to Vienna and offered to the emperor for two thousand thalers. The discoverers pretended to have found it in a subterranean chamber at Jerusalem which bore the Chaldean inscription: "Here lies the giant Og." But this was too great a strain on the faith of a very credulous age, and the emperor declined to purchase because, as Lambecius quaintly says, "The whole thing looked very like an imposition."

Don Quixote supported his chivalrous beliefs with similar evidence. "In the island of Sicily," he says, "there have been found long bones, and shoulderbones so huge that their size manifests their owners to have been giants, and as big as great towers; for this truth geometry sets beyond doubt." But the catalogue of mediaeval giants would fill a volume, and a very considerable literature on "gigantology" dates from that time. The learned, however, did not always accept these myths. One favorite way of escaping the difficulty was to declare fossil bones and teeth to be mere sports of nature generated in the earth by the "tumultuous movements of terrestrial exhalations," as was held by the famous anatomist of Padua, Falloppio (1550), who even went so far as to consider the remains of Roman art mere natural impressions stamped on the soil. Father Kircher (1680) adopts the same notion, and ridicules the idea of such monstrous giants, adding that he had himself seen these teeth in all stages of manufacture. Swift satirizes this school, whose professors "have invented this wonderful solution of all difficulties, to the unspeakable advancement of human knowledge."

By this time anatomists began to recognize the fact that these great bones and teeth belonged to elephants, and at once a new crop of theories sprang up to account for the new marvel . A prevalent view was that these were the remains of military elephants of the Romans, or of Hannibal, or Alexander the Great. This theory found an ardent advocate in Peter the Great; but, nevertheless, it was found to be insufficient, and that other wonderful solution of all difficulties, Noah's deluge, was called in to account for the anomaly.

The abundance of elephant remains in Siberia had long been known in Europe, as fossil ivory formed an important article of commerce. Isbrand Ides, in his travels from Moscow to China (1692), examined into the matter, and his account is worth quoting: "The heathens of Jakuti, Tungusi, and Ostiaki say that they [the mammoths] continually, or at least by reason of the very hard frost, mostly live under ground, where they go backwards and forward. . . . They further believe that if this animal comes so near the surface as to smell or discern the air, he immediately dies, which, they say, is the reason why so many of them are found on the high banks where they come out of the ground. This is the opinion of the infidels concerning these beasts, which are never seen." Ides states that the Russians, on the other hand, consider the mammoths to be elephants which were drowned in the flood, and Lawrence Lang adds that some believed these to be the behemoth of Job, "the description whereof, they pretend, fits the nature of this beast; . . . those supposed words in particular, he is caught with his own eyes, agreeing with the Siberian tradition that the maman beast dies on coming to the light."

The Siberian myths even penetrated to China, as Von Olfers has shown. A Chinese account of a journey to the Caspian in 1712 says: "In the coldest parts of this northern land there is a sort of animal which burrows under the earth, and which dies as soon as it is brought to light or the air. It is of great size, and weighs thirteen thousand pounds. It is by nature not a strong animal, and is therefore not very fierce or dangerous. It is usually found in the mud on the banks of rivers. The Russians usually collect the bones, in order to make cups, dishes, and other small wares of them. The flesh of the animal is of a very cooling sort, and is used as a remedy for fever." Other Chinese versions of the same story are known, and one of the sages, in commenting upon it, remarks that earthquakes are no longer an insoluble problem; the burrowing of the mammoth explains the matter most satisfactorily. In China itself the fossil bones masquerade as the familiar dragon, and some of the dragon bones and teeth figured in Chinese works are plainly the remains of elephants.

Don Quixote supported his chivalrous beliefs with similar evidence. "In the island of Sicily," he says, "there have been found long bones, and shoulderbones so huge that their size manifests their owners to have been giants, and as big as great towers; for this truth geometry sets beyond doubt." But the catalogue of mediaeval giants would fill a volume, and a very considerable literature on "gigantology" dates from that time. The learned, however, did not always accept these myths. One favorite way of escaping the difficulty was to declare fossil bones and teeth to be mere sports of nature generated in the earth by the "tumultuous movements of terrestrial exhalations," as was held by the famous anatomist of Padua, Falloppio (1550), who even went so far as to consider the remains of Roman art mere natural impressions stamped on the soil. Father Kircher (1680) adopts the same notion, and ridicules the idea of such monstrous giants, adding that he had himself seen these teeth in all stages of manufacture. Swift satirizes this school, whose professors "have invented this wonderful solution of all difficulties, to the unspeakable advancement of human knowledge."

By this time anatomists began to recognize the fact that these great bones and teeth belonged to elephants, and at once a new crop of theories sprang up to account for the new marvel . A prevalent view was that these were the remains of military elephants of the Romans, or of Hannibal, or Alexander the Great. This theory found an ardent advocate in Peter the Great; but, nevertheless, it was found to be insufficient, and that other wonderful solution of all difficulties, Noah's deluge, was called in to account for the anomaly.

The abundance of elephant remains in Siberia had long been known in Europe, as fossil ivory formed an important article of commerce. Isbrand Ides, in his travels from Moscow to China (1692), examined into the matter, and his account is worth quoting: "The heathens of Jakuti, Tungusi, and Ostiaki say that they [the mammoths] continually, or at least by reason of the very hard frost, mostly live under ground, where they go backwards and forward. . . . They further believe that if this animal comes so near the surface as to smell or discern the air, he immediately dies, which, they say, is the reason why so many of them are found on the high banks where they come out of the ground. This is the opinion of the infidels concerning these beasts, which are never seen." Ides states that the Russians, on the other hand, consider the mammoths to be elephants which were drowned in the flood, and Lawrence Lang adds that some believed these to be the behemoth of Job, "the description whereof, they pretend, fits the nature of this beast; . . . those supposed words in particular, he is caught with his own eyes, agreeing with the Siberian tradition that the maman beast dies on coming to the light."

The Siberian myths even penetrated to China, as Von Olfers has shown. A Chinese account of a journey to the Caspian in 1712 says: "In the coldest parts of this northern land there is a sort of animal which burrows under the earth, and which dies as soon as it is brought to light or the air. It is of great size, and weighs thirteen thousand pounds. It is by nature not a strong animal, and is therefore not very fierce or dangerous. It is usually found in the mud on the banks of rivers. The Russians usually collect the bones, in order to make cups, dishes, and other small wares of them. The flesh of the animal is of a very cooling sort, and is used as a remedy for fever." Other Chinese versions of the same story are known, and one of the sages, in commenting upon it, remarks that earthquakes are no longer an insoluble problem; the burrowing of the mammoth explains the matter most satisfactorily. In China itself the fossil bones masquerade as the familiar dragon, and some of the dragon bones and teeth figured in Chinese works are plainly the remains of elephants.

|

Curiously enough, the earliest mention of any American elephant is from the pen of "smattering, chattering, would-be college-president, Cotton Mather" (as Holmes calls him). This is a letter published in the "Philosophical Transactions" for 1714 The great witch-catcher confirms the scriptural account of antediluvian giants, just as St. Augustine had done before him, by describing elephants' bones and teeth, particularly by a tooth brought to New York in 1705, with a thigh-bone seventeen feet long. "There was another [tooth], near a pound heavier, found near the banks of Hudson's River, about fifty leagues from the sea, a great way below the surface of the earth, where the ground is of a different color and substance from the other ground for seventy-five feet long, which they supposed to be from the rotting of the body to which these bones and teeth did, as he supposes, once belong." Governor Dudley, of Massachusetts, wrote of these same bones to Cotton Mather, that he was "perfectly of opinion that the tooth will agree only to a human body, for whom the flood only could prepare a funeral; and, without doubt, he waded as long as he could keep his head above the clouds, but must, at length, be confounded with all other creatures."

|

The remains of mastodons and elephants are scattered so abundantly over the United States that they very soon attracted the general attention of the settlers, as they had already done in the case of the Indians. The early accounts deal much with the marvellous, the giant theory of Mather and Dudley Wing the favorite, though the Indian traditions found acceptance with many. The French anatomist, Daubenton, first showed that these were elephants’ bones, but William Hunter (in 1767) advanced a theory which has shown an astonishing vitality. Wing repeated with variations down to a comparatively recent period. Hunter showed to his own complete satisfaction that the mastodon (and he supposed the mammoth to be the same) was not an elephant at all, but a huge carnivorous animal, and concludes: "And if this animal was indeed carnivorous, which I believe cannot be doubted, though we may as philosophers regret it, as men we cannot but thank heaven that its whole generation is probably extinct."

Washington and Jefferson, little us we are accustomed to think of them as men of Science, both allowed considerable interest in the subject of these curious bones. Robert Annan had a collection of such remains at his house in Central New York, and writes: "His Excellency, General Washington, came to my house to see these relics. He told me he had in his house a grinder, which was found on the Ohio, much mumbling these." Jefferson, on the other hand, wrote voluminously on the subject. In his "Notes on Virginia" he breaks a lance with Buffon, who had ventured to cast aspersions on the size of American animals. In speaking of the mastodon, which, like all the writers of his time, he confounds with the mammoth, he says: "That it was not an elephant, I think ascertained by proofs equally decisive. I will not avail myself of the authority of the celebrated anatomist who, from an examination of the form and structure of the tusks, has declared they were essentially different from those of the elephant, because another anatomist, equally celebrated, has declared, on a like examination, that they are precisely the same. But (1) the skeleton of the mammoth bespeaks an animal of five or six times the cubic volume of the elephant, as M. de Buffon has admitted. (2) The grinders are five times as large, are square, and the grinding surface studded with five or six rows of blunt points, whereas those of the elephant are broad and thin, and the grinding surface flat. (3) I have never heard of an instance, and suppose there has been none, of the grinder of an elephant being found in America. (4) From the known temperature and constitution of the elephant, he could never have existed in those regions where the remains of the mammoth have been found. . . . The centre of the frozen zone may have been their acme of vigor, as that of the torrid is of the elephant. Thus nature seems to have drawn a belt of separation between these two tremendous animals. . . . When the Creator has therefore separated their nature so far as the extent of the scale of animal life will permit, it seems perverse to declare it the same from a partial resemblance of their tusks and bones. . . .

"It may be asked why I insert the mammoth as if it still existed. I ask in return why I should omit it as if it did not exist. Such is the economy of nature that no instance can be produced of her having permitted any one race of her animals to become extinct, of her having formed any link in her great chain so weak as to be broken. . . .

"The northern and western parts of America still remain in their aboriginal state, unexplored by us or by others for us; he may as well exist there now as he did formerly where we find his bones."

This doctrine of the indestructibility of species was an accepted scientific dogma of Jefferson's time, but it pushed him to great extremities when he came later to describe his Megalonyx, which he believed to be a gigantic lion, but which in reality was a huge sloth. To prove that this dreadful creature was still alive, he had recourse to hunters' tales about vast animals whose roarings shook the earth, and which carried off horses like so many sheep. "The movements of nature," he argues, "are in a never-ending circle. The animal species which has once been put into a train of motion is still probably moving in that train. For, if one link in nature's chain might be lost, another and another might be lost, till this whole system of things should evanish by piecemeal."

Amusing and even absurd as all this may seem to us now, it is but justice to say that Jefferson rendered distinguished services to science, by the stimulus which he gave to inquiry and discussion of scientific problems; and the collections of fossil bones which, as President of the United States, he caused to be made in the West, have proved to be of very great value and importance.

It would be tedious to enumerate half the writers who followed Jefferson in discussing the nature of the mammoth. Nearly all of them regarded the creature as a gigantic flesh-eater, and exhausted all the adjectives of the language to describe his fierceness and blood-thirstiness. Some of these savants, not content with nature's handiwork, concocted the most gruesome monsters by putting together bones of many different animals, and then lashed themselves into a frenzy over their own creations. A few specimens will give a sufficient idea of the writings of this school, which make up quite a literature of their own.

"Now, may we not infer from these facts that nature had allotted to the mammoth the beasts of the forest for his food? How can we otherwise account for the numerous fractures which everywhere mark these strata of bones? May it not be inferred, too, that as the largest and swiftest quadrupeds were appointed for his food, he necessarily was endowed with great strength and activity? That as the immense volume of the creature would unfit him for coursing after his prey through thickets and woods, nature had furnished him with the power of taking it by a mighty leap? That this power of springing to a great distance was requisite to the more effectual concealment of his great bulk, while lying in wait for his prey? The Author of existence is wise and just in all his works; he never confers an appetite without the power to gratify it" (George Turner, 1797).

Washington and Jefferson, little us we are accustomed to think of them as men of Science, both allowed considerable interest in the subject of these curious bones. Robert Annan had a collection of such remains at his house in Central New York, and writes: "His Excellency, General Washington, came to my house to see these relics. He told me he had in his house a grinder, which was found on the Ohio, much mumbling these." Jefferson, on the other hand, wrote voluminously on the subject. In his "Notes on Virginia" he breaks a lance with Buffon, who had ventured to cast aspersions on the size of American animals. In speaking of the mastodon, which, like all the writers of his time, he confounds with the mammoth, he says: "That it was not an elephant, I think ascertained by proofs equally decisive. I will not avail myself of the authority of the celebrated anatomist who, from an examination of the form and structure of the tusks, has declared they were essentially different from those of the elephant, because another anatomist, equally celebrated, has declared, on a like examination, that they are precisely the same. But (1) the skeleton of the mammoth bespeaks an animal of five or six times the cubic volume of the elephant, as M. de Buffon has admitted. (2) The grinders are five times as large, are square, and the grinding surface studded with five or six rows of blunt points, whereas those of the elephant are broad and thin, and the grinding surface flat. (3) I have never heard of an instance, and suppose there has been none, of the grinder of an elephant being found in America. (4) From the known temperature and constitution of the elephant, he could never have existed in those regions where the remains of the mammoth have been found. . . . The centre of the frozen zone may have been their acme of vigor, as that of the torrid is of the elephant. Thus nature seems to have drawn a belt of separation between these two tremendous animals. . . . When the Creator has therefore separated their nature so far as the extent of the scale of animal life will permit, it seems perverse to declare it the same from a partial resemblance of their tusks and bones. . . .

"It may be asked why I insert the mammoth as if it still existed. I ask in return why I should omit it as if it did not exist. Such is the economy of nature that no instance can be produced of her having permitted any one race of her animals to become extinct, of her having formed any link in her great chain so weak as to be broken. . . .

"The northern and western parts of America still remain in their aboriginal state, unexplored by us or by others for us; he may as well exist there now as he did formerly where we find his bones."

This doctrine of the indestructibility of species was an accepted scientific dogma of Jefferson's time, but it pushed him to great extremities when he came later to describe his Megalonyx, which he believed to be a gigantic lion, but which in reality was a huge sloth. To prove that this dreadful creature was still alive, he had recourse to hunters' tales about vast animals whose roarings shook the earth, and which carried off horses like so many sheep. "The movements of nature," he argues, "are in a never-ending circle. The animal species which has once been put into a train of motion is still probably moving in that train. For, if one link in nature's chain might be lost, another and another might be lost, till this whole system of things should evanish by piecemeal."

Amusing and even absurd as all this may seem to us now, it is but justice to say that Jefferson rendered distinguished services to science, by the stimulus which he gave to inquiry and discussion of scientific problems; and the collections of fossil bones which, as President of the United States, he caused to be made in the West, have proved to be of very great value and importance.

It would be tedious to enumerate half the writers who followed Jefferson in discussing the nature of the mammoth. Nearly all of them regarded the creature as a gigantic flesh-eater, and exhausted all the adjectives of the language to describe his fierceness and blood-thirstiness. Some of these savants, not content with nature's handiwork, concocted the most gruesome monsters by putting together bones of many different animals, and then lashed themselves into a frenzy over their own creations. A few specimens will give a sufficient idea of the writings of this school, which make up quite a literature of their own.

"Now, may we not infer from these facts that nature had allotted to the mammoth the beasts of the forest for his food? How can we otherwise account for the numerous fractures which everywhere mark these strata of bones? May it not be inferred, too, that as the largest and swiftest quadrupeds were appointed for his food, he necessarily was endowed with great strength and activity? That as the immense volume of the creature would unfit him for coursing after his prey through thickets and woods, nature had furnished him with the power of taking it by a mighty leap? That this power of springing to a great distance was requisite to the more effectual concealment of his great bulk, while lying in wait for his prey? The Author of existence is wise and just in all his works; he never confers an appetite without the power to gratify it" (George Turner, 1797).

|

"With the agility and ferocity of the tiger, with a body of unequalled magnitude and strength, this monster must have been the terror of the forest and of man. ... In fine, 'huge as the frowning precipice, cruel as the bloody panther, swift as the descending eagle, and terrible as the angel of night' must hare been this tremendous animal when clothed with flesh and animated with principles of life. . . . From this rapid review of these majestic remains it must appear that the creature to whom they belonged was nearly sixty feet long and twenty-five feet high" (Thomas Ashe, 1801).

|

But all this fine rhetoric was ruthlessly dashed by Cuvier, who early in the present century showed that the dire destroyer was only an extinct elephant. The great lesson which Cuvier taught the world was, that many races of animals were entirely extinct, and that nature's chain of existence had not one, but many missing links. From his recognition of that fact the science of palaeontology may be said to date. But the carnivorous nature of the mastodon was too fascinating an absurdity to be so easily killed, and it continued to appear at intervals. As late as 1835 we find a New England medical professor writing as if it were an unquestionable fact. The giant theory lingered still longer, and even yet cannot be considered entirely extinct among the unlearned. The dictum that the superstitions of one age are but the science of preceding ages receives ample confirmation in the history of this subject. Not longer ago than 1846 a mastodon skeleton was exhibited in New Orleans as that of a giant. The cranium was made of raw hide, fantastic wooden teeth were fitted in the jaws, all missing parts were restored after the human model, and the whole raised upon the hind legs. It certainly conveyed the notion of "a hideous, diabolical giant," and was no doubt responsible for many nightmares. As a sad commentary on the state of the medical profession in the Southwest at that time, it may be added that the exhibitor was perfectly honest in his belief, and to support his faith he had a trunk full of physicians' certificates that these were human bones.

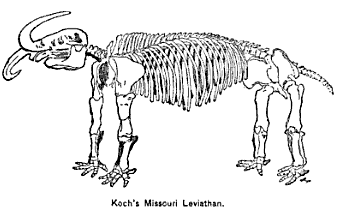

In 1840 "Dr." Koch, a German charlatan, created a great sensation by announcing the discovery of the leviathan of Job, which he called the Missourium, from the State where it was found. It turned out, however, to be nothing but a mastodon preposterously mounted. Koch had added an extra dozen or more joints to the back-bone and ribs to the chest, turned the tusks outward into a semicircle, and converted the animal into an aquatic monster which anchored itself to trees by means of its sickle-shaped tusks and then peacefully slumbered on the bosom of the waves. Like the Siberians, he found interesting confirmations of his views in the book of Job, that refuge of perplexed monster-makers. Koch took his leviathan to London, where it was purchased by the British Museum, and reconverted into a mastodon by Professor Owen, who at once recognized its true nature.

In 1840 "Dr." Koch, a German charlatan, created a great sensation by announcing the discovery of the leviathan of Job, which he called the Missourium, from the State where it was found. It turned out, however, to be nothing but a mastodon preposterously mounted. Koch had added an extra dozen or more joints to the back-bone and ribs to the chest, turned the tusks outward into a semicircle, and converted the animal into an aquatic monster which anchored itself to trees by means of its sickle-shaped tusks and then peacefully slumbered on the bosom of the waves. Like the Siberians, he found interesting confirmations of his views in the book of Job, that refuge of perplexed monster-makers. Koch took his leviathan to London, where it was purchased by the British Museum, and reconverted into a mastodon by Professor Owen, who at once recognized its true nature.

|

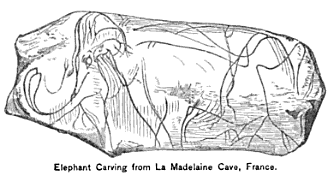

From this time on, discoveries of mastodon bones were so frequently announced that popular interest in the matter gradually died away until it was revived by evidence that these elephants had become extinct since the appearance of man on the continent. This evidence is threefold—geological, traditional, and the proof derived from works of art. In Europe the evidence has been submitted to the most searching examination, and there is no possible room for doubt that, on that continent, the mammoth or hairy elephant coexisted with prehistoric man. Not only are the bones of these animals found in the same caves and deposits with human bones and implements of human workmanship, but we have a number of unmistakable portraits of the mammoth engraved on ivory and stone. One of these on ivory, from the Madelaine cave in France, is an exceedingly spirited and accurate drawing. The prehistoric artist who drew that figure must have been very familiar with the living animal.

|

In America the evidence was long doubtful, but cannot be considered so any longer. Mastodon bones occur in this country in much more recent deposits than they do in Europe, often covered by only a few inches of soil or peat, and in such a state of preservation as to make it difficult to believe that they are more than a few centuries old. In California human bones and stone implements have been found in the gold-bearing gravels associated with the remains of mastodons, mammoths, and other extinct animals. In Oregon the mastodon bones so abundant near Silver Lake are commingled with flint arrow- and spear-heads; and very recently a human skeleton has been discovered in Mexico embedded in a calcareous deposit which also contained elephant bones. These facts remove all reasonable doubt that man had appeared in America before the disappearance of the elephants. A much more difficult question is to decide what race of men they were. The discoveries in California point to a very high antiquity, as the gold-bearing gravels are covered over with great beds of hard lava which have been completely cut through into canons by the action of the streams, and the topography of the country materially changed. These processes are slow, and indicate a great lapse of time. In the East there is reason to believe that the antiquity is not so high. In this connection the Indian traditions are of importance.

Longueil, the French traveller, who saw the great skeletons at Big-bone Lick in 1739, mentions the reverence in which the Indians held these, and states that they never removed or disturbed them. Jefferson gives the following tradition of the Delawares, about the "big buffalo:" "That in ancient times, a herd of these tremendous animals came to the Bigbone Licks, and commenced a universal destruction of the bear, deer, elks, buffaloes, and other animals which had been created for the use of the Indians; that the Great Man above, looking down and seeing this, became so enraged that he seized his lightning, descended on the earth, seated himself on a neighboring mountain on a rock, on which his seat and the prints of his feet are still to be seen, and hurled his bolts among them till the whole were slaughtered, except the big bull, who, presenting his forehead to the shafts, shook them off as they fell, but missing one at length, it wounded him in the side; whereupon, springing round, he bounded over the Ohio, over the Wabash, the Illinois, and finally over the great lakes, where he is living to this day." Jefferson also quotes the narrative of a Mr. Stanley who was captured by the Indians near the mouth of the Tennessee River and carried westward beyond the Missouri to a place where these great bones were abundant. The Indians declared that the animal to which they belonged was still living in the north, and from their descriptions Stanley inferred it to be an elephant.

Pere Charlevoix, a Jesuit missionary, mentions in his history of New France an Indian tradition of a great elk, "beside whom others seem like ants. He has, they say, legs so high that eight feet of snow do not embarrass him; his skin is proof against all sorts of weapons, and he has a sort of arm which comes out of his shoulder, and which he uses as we do ours." As Tyler has remarked, this tradition seems to point to a remembrance of some elephant-like animal, for nothing but observation of the living form could give a savage a notion of the use of an elephant's trunk. Even the perfectly preserved frozen carcasses of Siberia did not give the natives any idea of it, and their myths make no mention of such an organ. An old Sioux who had seen an elephant in a menagerie described it to his friends at home as a beast with two tails, which would certainly be the view suggested to an Indian by the carcass of such an animal.

Still more explicit is a tradition given by Mather of some Ohio Indians, which seems to refer to the mastodon, and according to which these animals were abundant; they fed on the boughs of a species of lime-tree; they did not lie down, but leaned against a tree to sleep. The Indians of Louisiana named one of the streams Carrion-crow Creek, because in the time of their fathers a huge animal had died near this creek, and great numbers of crows flocked to the carcass; a mastodon skeleton was found near the spot indicated by the Indians.

Traditions of a similar import are recorded from the Iroquois, Wyandots, Tuscaroras, and other tribes, and perhaps most interesting of all is a widely spread legend among the tribes of the Northwest British provinces, that their ancestors had built lake-dwellings on piles like those of Switzerland, "to protect themselves against an animal which ravaged the country long, long ago. This, from description, was no doubt the mastodon. I find the tradition identical among the Indians of the Suogualami and Peace Rivers, who have no connection with each other; but in both localities remains of that animal are found abundantly." So suggestive were these Indian tales that on some of the early maps of North America the mammoth is given as an inhabitant of Labrador.

In Mexico and South America we meet with a series of myths which form a curious parallel to those of the Old World. Bernal Diaz del Castillo reports among the Mexicans at the time of the Spanish conquest the existence of legends of giants, founded upon the occurrence of huge bones. The following is related of Tlascalla: "The tradition was also handed down from their forefathers that in ancient times there lived here a race of men and women of immense stature, with heavy bones, and were a very bad and evil-disposed people, whom they had for the most part exterminated by continual war, and the few that were left gradually died away. In order to give us a notion of the huge frame of these people they dragged forth a thigh-bone of one of these giants, which was very strong, and measured the length of a man of good stature. This bone was still entire from the knee to the hip-joint. I measured it by my own person, and found it to be of my own length, although I am a man of considerable height. They showed us many similar pieces of bones, but they were all worm-eaten and decayed; we, however, did not doubt for an instant that this country was once inhabited by giants. Cortes observed that we ought to forward these bones to his Majesty in Spain by the very first opportunity." He also found similar bones placed as offerings in the temple at Cojohuacan, near Mexico.

Humboldt collected similar legends in South America. In Guayaquil the tale of a colony of giants grew out of the mastodon bones which are found there. The finding of such bones near Bogota produced speculations which are a curious repetition of mediaeval philosophy. "The Indians imagined that these were giants' bones, while the half-learned sages of the country, who assume the right of explaining everything, gravely asserted that they were mere sports of nature and little worthy of attention."

The natives who guided Darwin to some mastodon skeletons on the Parana River had a tradition which is very important as showing how the same myths can arise independently in very widely separated localities. As these bones occurred in the bluffs of the river, the conclusion was reached that the mastodon was a burrowing animal, exactly as the Siberians had inferred from similar evidence in the case of the mammoth. In the pampas, on the other hand, the ever-recurring myth of giants prevails, and such local names as the Field of the Giants, Hill of the Giant, require no comment.

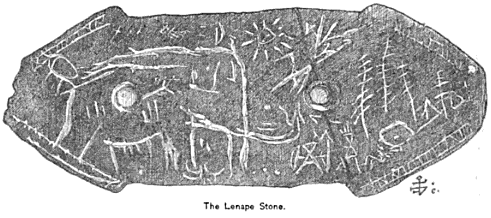

Remains of aboriginal art which point to a knowledge of living elephants are not numerous. None is certainly known of Indian workmanship, as the famous Lenape stone is altogether too questionable to be allowed any weight in the argument. Nor do the Mound Builders seem to have made use of the elephant's form in their pottery or sculptures.

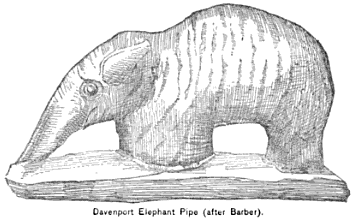

The Davenport elephant pipes would seem to remove this difficulty, but very grave doubts have been cast upon their authenticity. There is, however, in Grant County, Wis., a large mound, the shape of which is very suggestive of an elephant, but even here the latest surveys tend to cast doubt upon the elephant theory.

Pere Charlevoix, a Jesuit missionary, mentions in his history of New France an Indian tradition of a great elk, "beside whom others seem like ants. He has, they say, legs so high that eight feet of snow do not embarrass him; his skin is proof against all sorts of weapons, and he has a sort of arm which comes out of his shoulder, and which he uses as we do ours." As Tyler has remarked, this tradition seems to point to a remembrance of some elephant-like animal, for nothing but observation of the living form could give a savage a notion of the use of an elephant's trunk. Even the perfectly preserved frozen carcasses of Siberia did not give the natives any idea of it, and their myths make no mention of such an organ. An old Sioux who had seen an elephant in a menagerie described it to his friends at home as a beast with two tails, which would certainly be the view suggested to an Indian by the carcass of such an animal.

Still more explicit is a tradition given by Mather of some Ohio Indians, which seems to refer to the mastodon, and according to which these animals were abundant; they fed on the boughs of a species of lime-tree; they did not lie down, but leaned against a tree to sleep. The Indians of Louisiana named one of the streams Carrion-crow Creek, because in the time of their fathers a huge animal had died near this creek, and great numbers of crows flocked to the carcass; a mastodon skeleton was found near the spot indicated by the Indians.

Traditions of a similar import are recorded from the Iroquois, Wyandots, Tuscaroras, and other tribes, and perhaps most interesting of all is a widely spread legend among the tribes of the Northwest British provinces, that their ancestors had built lake-dwellings on piles like those of Switzerland, "to protect themselves against an animal which ravaged the country long, long ago. This, from description, was no doubt the mastodon. I find the tradition identical among the Indians of the Suogualami and Peace Rivers, who have no connection with each other; but in both localities remains of that animal are found abundantly." So suggestive were these Indian tales that on some of the early maps of North America the mammoth is given as an inhabitant of Labrador.

In Mexico and South America we meet with a series of myths which form a curious parallel to those of the Old World. Bernal Diaz del Castillo reports among the Mexicans at the time of the Spanish conquest the existence of legends of giants, founded upon the occurrence of huge bones. The following is related of Tlascalla: "The tradition was also handed down from their forefathers that in ancient times there lived here a race of men and women of immense stature, with heavy bones, and were a very bad and evil-disposed people, whom they had for the most part exterminated by continual war, and the few that were left gradually died away. In order to give us a notion of the huge frame of these people they dragged forth a thigh-bone of one of these giants, which was very strong, and measured the length of a man of good stature. This bone was still entire from the knee to the hip-joint. I measured it by my own person, and found it to be of my own length, although I am a man of considerable height. They showed us many similar pieces of bones, but they were all worm-eaten and decayed; we, however, did not doubt for an instant that this country was once inhabited by giants. Cortes observed that we ought to forward these bones to his Majesty in Spain by the very first opportunity." He also found similar bones placed as offerings in the temple at Cojohuacan, near Mexico.

Humboldt collected similar legends in South America. In Guayaquil the tale of a colony of giants grew out of the mastodon bones which are found there. The finding of such bones near Bogota produced speculations which are a curious repetition of mediaeval philosophy. "The Indians imagined that these were giants' bones, while the half-learned sages of the country, who assume the right of explaining everything, gravely asserted that they were mere sports of nature and little worthy of attention."

The natives who guided Darwin to some mastodon skeletons on the Parana River had a tradition which is very important as showing how the same myths can arise independently in very widely separated localities. As these bones occurred in the bluffs of the river, the conclusion was reached that the mastodon was a burrowing animal, exactly as the Siberians had inferred from similar evidence in the case of the mammoth. In the pampas, on the other hand, the ever-recurring myth of giants prevails, and such local names as the Field of the Giants, Hill of the Giant, require no comment.

Remains of aboriginal art which point to a knowledge of living elephants are not numerous. None is certainly known of Indian workmanship, as the famous Lenape stone is altogether too questionable to be allowed any weight in the argument. Nor do the Mound Builders seem to have made use of the elephant's form in their pottery or sculptures.

The Davenport elephant pipes would seem to remove this difficulty, but very grave doubts have been cast upon their authenticity. There is, however, in Grant County, Wis., a large mound, the shape of which is very suggestive of an elephant, but even here the latest surveys tend to cast doubt upon the elephant theory.

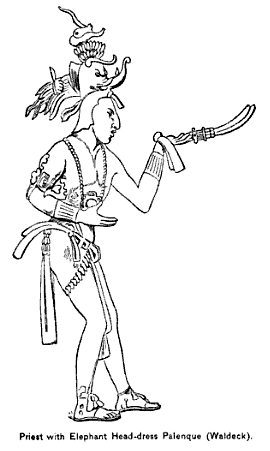

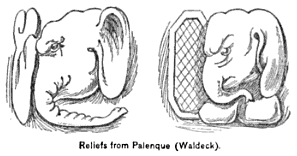

In Mexico there are many indications that elephants were known to the ancient inhabitants. Some of the bas-reliefs of Palenque figured by Waldeck are very strikingly like elephants, and the resemblance can hardly be the result of accident or coincidence. Close to an ancient causeway near Tezcuco, in what may have been the ditch of the road, an entire mastodon skeleton was found, which "bore every appearance of having been coeval with the period when the road was used." Humboldt reproduces a figure from a Mexican manuscript representing a human sacrifice, and says of it: "The disguise of the sacrificing priest presents a remarkable and apparently not accidental resemblance to the Hindoo Ganesa [the elephant-headed god]. . . . Had the peoples of Aztlan derived from Asia some vague notions of the elephant, or, as seems to me much less probable, did their traditions reach back to the time when America was still inhabited by these gigantic animals, whose petrified skeletons are found buried in the marly ground on the very ridge of the Mexican Cordilleras?"

Taken altogether, the evidence from tradition and art is strongly in favor of the view that the ancestors of existing American races knew these monstrous animals familiarly. Undoubtedly there is much of fable and absurdity in their legends, but there is something in these tales that is very like truth. The traditions of Europe, Siberia, and South America are plainly derived only from the finding of the bones, and in all the elaborate and often-repeated stories of giants and subterranean monsters we may search in vain for any knowledge of the living animal. The myths of the North American Indians, on the contrary, are irresistibly suggestive of elephants, and, as we have already seen, they convinced some of the early settlers that these animals were still to be found in the north. Traditions from other regions—the burrowers of Siberia, the dragons of China, and the giants of nearly all countries—are plainly nothing but attempts to account for the large bones which occur in the ground; but the Indian legends can be explained in no such way. Other Indian traditions, such as that of the "naked bear," seem to point clearly to the gigantic extinct sloths; and the fact that the mythical animals can be distinguished apart, and referred to appropriate originals in the extinct animals of the continent, speaks strongly for the accuracy of the stories.

The Mexican sculptures are of less value in this discussion, as there are so many striking correspondences between the ancient Mexican civilization and that of certain Asiatic tribes that, as Humboldt suggests, the form of the elephant may have been derived from Asia. But from the geological evidence this is unlikely. At all events the existence of the giant-myth in Mexico is no argument against a traditional knowledge of the living animals, as the oral tradition of the latter may well coexist with the conjectures about huge bones, resulting in tales of giants. Elephants are certainly familiar enough objects in India, and yet even there the petrified elephant bones of the Sivalik Hills are called by the natives giants' bones, belonging to the slain Rakis, the gigantic Rakshasas of Hindoo mythology.

Altogether, then, the testimony—geological, archaeological, and traditional—goes to show that not very many centuries ago elephants were an important element in American life.

Taken altogether, the evidence from tradition and art is strongly in favor of the view that the ancestors of existing American races knew these monstrous animals familiarly. Undoubtedly there is much of fable and absurdity in their legends, but there is something in these tales that is very like truth. The traditions of Europe, Siberia, and South America are plainly derived only from the finding of the bones, and in all the elaborate and often-repeated stories of giants and subterranean monsters we may search in vain for any knowledge of the living animal. The myths of the North American Indians, on the contrary, are irresistibly suggestive of elephants, and, as we have already seen, they convinced some of the early settlers that these animals were still to be found in the north. Traditions from other regions—the burrowers of Siberia, the dragons of China, and the giants of nearly all countries—are plainly nothing but attempts to account for the large bones which occur in the ground; but the Indian legends can be explained in no such way. Other Indian traditions, such as that of the "naked bear," seem to point clearly to the gigantic extinct sloths; and the fact that the mythical animals can be distinguished apart, and referred to appropriate originals in the extinct animals of the continent, speaks strongly for the accuracy of the stories.

The Mexican sculptures are of less value in this discussion, as there are so many striking correspondences between the ancient Mexican civilization and that of certain Asiatic tribes that, as Humboldt suggests, the form of the elephant may have been derived from Asia. But from the geological evidence this is unlikely. At all events the existence of the giant-myth in Mexico is no argument against a traditional knowledge of the living animals, as the oral tradition of the latter may well coexist with the conjectures about huge bones, resulting in tales of giants. Elephants are certainly familiar enough objects in India, and yet even there the petrified elephant bones of the Sivalik Hills are called by the natives giants' bones, belonging to the slain Rakis, the gigantic Rakshasas of Hindoo mythology.

Altogether, then, the testimony—geological, archaeological, and traditional—goes to show that not very many centuries ago elephants were an important element in American life.

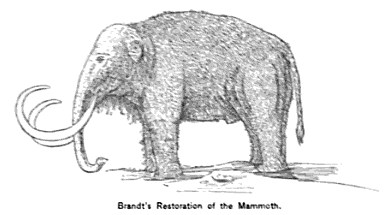

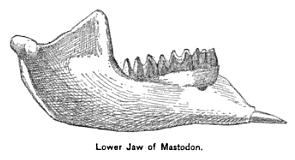

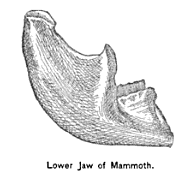

Now, what manner of beasts were these American elephants? At least two species, the mammoth and the mastodon, and perhaps others, occurred on this continent after the ice of the glacial period had melted and a more temperate climate again prevailed. The mastodon differed from other elephants in the shape and structure of the grinding teeth, and in the fact that the males possessed a small tusk in the lower jaw. The animal was of a comparatively low stature, averaging less than that of the living species of India; but the body was long and the limbs very massive; there may have been a hairy coat, but this is very uncertain. The mammoth (whose name is a Siberian word of probably Finnish origin) was a very different type of elephant from the mastodon or either of the existing species, though most like the Indian form. It was of vast size, reaching, in some cases, a height of sixteen feet; the tusks were very long, and spirally curved outward and backward, and the body was thickly covered with hair, which formed three distinct coats. The outer coat was long and coarse; beneath this was a layer of finer fur, and under this again a dense mass of soft, brownish wool. Both of these animals were adapted to a cold climate, and ranged far beyond the Arctic Circle, though the mastodon is rare in the far north; their food, as we may learn from the still preserved contents of the stomach, was chiefly the tender shoots and cones of the pine and fir.

The frozen carcasses of Siberia are in such a wonderful state of preservation that the mammoth is the best known of all extinct mammals, and the following description, by a Russian engineer who had the good fortune to see one of these giants disentombed by a flood, will serve to give a vivid conception of what the creature was like: "Picture to yourself an elephant, with a body covered with thick fur, about thirteen feet in height and fifteen in length, with tusks eight feet long, colossal limbs, and a tail naked up to the end, which was covered with thick, tufty hair. . . . The whole appearance of the animal was fearfully strange and wild; it had not the shape of our present elephants. . . . Our elephant is an awkward animal; but compared with this mammoth it is an Arabian steed to a coarse, ugly dray-horse. ... I had the stomach separated and brought on one side. It was well filled, and the contents well preserved and instructive. The principal were the young shoots of the fir and pine; a quantity of young fir-cones, also in a chewed state, were mixed with the moss."

It is very difficult to explain why these gigantic animals should have so completely vanished from the New World within (geologically speaking) such recent times. The agency of primeval man may have had something to do with it, but this cause alone is insufficient. Some unfavorable change, of which we do not yet know the nature, swept away a great population of large American mammals, leaving behind them but sparse and pigmy representatives. The strangest, hugest, and fiercest of these forms have entirely disappeared; a fact over which we may well rejoice, as, from our point of view, the world is a much pleasanter place without them, and we can heartily re-echo Hunter's pious ejaculation, and "thank heaven that the whole generation is extinct."

The frozen carcasses of Siberia are in such a wonderful state of preservation that the mammoth is the best known of all extinct mammals, and the following description, by a Russian engineer who had the good fortune to see one of these giants disentombed by a flood, will serve to give a vivid conception of what the creature was like: "Picture to yourself an elephant, with a body covered with thick fur, about thirteen feet in height and fifteen in length, with tusks eight feet long, colossal limbs, and a tail naked up to the end, which was covered with thick, tufty hair. . . . The whole appearance of the animal was fearfully strange and wild; it had not the shape of our present elephants. . . . Our elephant is an awkward animal; but compared with this mammoth it is an Arabian steed to a coarse, ugly dray-horse. ... I had the stomach separated and brought on one side. It was well filled, and the contents well preserved and instructive. The principal were the young shoots of the fir and pine; a quantity of young fir-cones, also in a chewed state, were mixed with the moss."

It is very difficult to explain why these gigantic animals should have so completely vanished from the New World within (geologically speaking) such recent times. The agency of primeval man may have had something to do with it, but this cause alone is insufficient. Some unfavorable change, of which we do not yet know the nature, swept away a great population of large American mammals, leaving behind them but sparse and pigmy representatives. The strangest, hugest, and fiercest of these forms have entirely disappeared; a fact over which we may well rejoice, as, from our point of view, the world is a much pleasanter place without them, and we can heartily re-echo Hunter's pious ejaculation, and "thank heaven that the whole generation is extinct."

Source: W. B. Scott, "American Elephant Myths," Scribner's, vol. 1 (April 1887): 469-478.