Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria

1881

|

NOTE |

CROWN PRINCE RUDOLF OF AUSTRIA (1858-1889) was the ill-fated son of the Emperor of Austria and heir to the imperial and royal thrones of the Habsburg monarchy before his infamous suicide at Mayerling in January 1889. Rudolf was an avid outdoorsman and an amateur naturalist with a keen, if bloodthirsty, interest in ornithology. On February 9, 1881, at the age of 23, he left Vienna on a voyage to the East, spending much of February and March in Egypt, in the company of Viennese illustrator Franz Xaver von Pausinger and the German Egyptologist Heinrich Karl Brugsch (a.k.a. Brugsch-Pasha), the latter of whom he had met at the Vienna World Exposition a few years earlier. In his 1894 autobiography, Brugsch praised Rudolf effusively, noting that the prince was possessed of extraordinary intelligence, a mature demeanor beyond his years, and an insatiable curiosity about all things scientific. Brugsch agreed to prepare some notes about Egypt for Rudolf to include in his volume describing the journey, published in late 1881 as Eine Orientreise (Travels in the East), and translated anonymously into English in 1884. Most importantly, Brugsch, who felt he had been treated badly by the Anglo-French condominium in Egypt, said that Rudolf's book offered "most eloquent evidence, with what kindness and indulgence the amiable Prince understood how to recognize my humble services." The passages below on the pyramids of Egypt, including sections by Brugsch, are condensed from the 300 (!) page discussion of Egypt (primarily focused on hunting and contemporary culture) in Rudolf's Travels.

|

TRAVELS IN THE EAST.

A delightful moment is at hand, when the monotony of the landscape of Lower Egypt draws to an end.

Here and there across the meadows we see, rising to the south-west, the yellow horizon of the Libyan desert; right in front, in the midday haze, as though veiled in orange grey, are the Pyramids of Ghizeh. It is a solemn moment, and unbidden thoughts of grave import fill the mind of the traveller, who sees for the first time with his own eyes these tokens of a civilization which flourished in long-past ages, in this everlasting land of the Pharaohs, which is the corner-stone of the history of the world.

To the south-east the table-like desert mountains of Mokattam rise in masses. Below them are the walls of the citadel and the minarets of the mosque of Mehmet Ali. Between all these, in the hot mist, lies the sea of houses of the chief city of Africa. The nearer we approach to the ancient, much-praised city of the Caliph, the more luxuriant are the gardens beside the railway. Forests of palms and sycamores surround isolated houses, and at length the dark green of the Schubra Avenue opens on our view. In a few minutes the train enters the station.

The Viceroy, surrounded by his officers of state, stood on the steps with most friendly greetings.

The numerous members of the large Austro-Hungarian colony received their countrymen with resounding ovations. We went to the carriages in waiting—handsome thoroughly European equipages—a battalion of infantry playing the National Hymn in our honour. The first sight of life in Cairo is enchanting. We drove through a short street to the bridge which crosses the canal, and into the rich green of the shady Schubra Avenue. One picture follows another, and as in a dream the most bewitching scenes pass before the eye. Crowds of human beings move to and fro; heavy-laden camels, small asses, noisy Orientals in coloured raiment; half-open shops and coffee-houses, customers squatting in front of them; children tumble in the dust; every one shouts and hustles; no one steps aside; terrified fellaheen women in blue skirts, carrying nurslings or water-pots on their heads, escape screaming at the quick approach of the carriages. The runners clear the way for our equipages with blows from their staves. To the right and left I notice neat houses within their own beautiful gardens. In a few moments we turn in through a trellised gate, where, amidst shrubs and thick plantations, stands the Castle of Kasr-en-Nusha. A division of infantry greeted us with a blast of horns.

The charming abode which the Viceroy had with the greatest kindness offered to us is a castle consisting of two square buildings. A gallery with large glazed windows over the entrance gate unites the two blocks; without and within everything is European, but the variety of the decorations, the gay hangings, the Eastern bath-rooms, and innumerable small details remind one at every turn that one is in the East.

We settled ourselves quickly, and were drinking in with delight the first impressions of Oriental life. The arrangement of the apartments, as well as the numerous charming terraces, the perfume of the flower garden, and the soft delicious air, reminded us of all the glories with which Eastern fancy adorns its tales. After a hasty breakfast some of our party went out hunting with Baron Saurma.

The town had to be traversed, and so we came once more across the canal, and drove through the European quarter, with its broad streets and the handsome houses and rich gardens of the wealthy. We saw from afar the entrance of the Arab quarter. The wild confusion of the streets amused us—European carriages, miserable droskies, donkeys for riding and for draft, mules, camels, rich and poor, beggars and gay Eastern folk, genuine Islamites and half-European Levantines; and besides all this the great crowd of Western folk—tourists, and the like. Passing Kasr-en-Nil we soon reached, driving across the bridge, the dykes and avenues which run between all the great gardens opposite to the city.

Near Tussum Pasha's castle, surrounded by canals and water-meadows, are extensive sugar-cane plantations. In one of these we proposed to hunt. Prince Taxis and the brother of Baron Saurma were on the spot waiting for us. The guns were placed and the dogs loosed.

For a long time the dachshunds seemed to find no scent; at last the chase began; a loud yelping approached the border of the field. Unluckily the wolf left his hiding at a spot where no gun was posted, and so we crossed a broad canal to another plantation. The dogs were let loose once more, but we were soon compelled to desist from our sport by the melancholy discovery, made while the dogs were driving the game, that the cutting of the sugar-cane had commenced on one side of the field.

Numerous labourers—very poor and scantily clad fellaheen, though some of them of most striking appearance— were working under the direction of an overseer robed in long full garments, and wielding a scourge made of thongs of rhinoceros hide. This worthy approached me with much dignity, and made a long speech accompanied with much gesticulation. I made out with some difficulty that he desired that I should leave the ground.

Here and there across the meadows we see, rising to the south-west, the yellow horizon of the Libyan desert; right in front, in the midday haze, as though veiled in orange grey, are the Pyramids of Ghizeh. It is a solemn moment, and unbidden thoughts of grave import fill the mind of the traveller, who sees for the first time with his own eyes these tokens of a civilization which flourished in long-past ages, in this everlasting land of the Pharaohs, which is the corner-stone of the history of the world.

To the south-east the table-like desert mountains of Mokattam rise in masses. Below them are the walls of the citadel and the minarets of the mosque of Mehmet Ali. Between all these, in the hot mist, lies the sea of houses of the chief city of Africa. The nearer we approach to the ancient, much-praised city of the Caliph, the more luxuriant are the gardens beside the railway. Forests of palms and sycamores surround isolated houses, and at length the dark green of the Schubra Avenue opens on our view. In a few minutes the train enters the station.

The Viceroy, surrounded by his officers of state, stood on the steps with most friendly greetings.

The numerous members of the large Austro-Hungarian colony received their countrymen with resounding ovations. We went to the carriages in waiting—handsome thoroughly European equipages—a battalion of infantry playing the National Hymn in our honour. The first sight of life in Cairo is enchanting. We drove through a short street to the bridge which crosses the canal, and into the rich green of the shady Schubra Avenue. One picture follows another, and as in a dream the most bewitching scenes pass before the eye. Crowds of human beings move to and fro; heavy-laden camels, small asses, noisy Orientals in coloured raiment; half-open shops and coffee-houses, customers squatting in front of them; children tumble in the dust; every one shouts and hustles; no one steps aside; terrified fellaheen women in blue skirts, carrying nurslings or water-pots on their heads, escape screaming at the quick approach of the carriages. The runners clear the way for our equipages with blows from their staves. To the right and left I notice neat houses within their own beautiful gardens. In a few moments we turn in through a trellised gate, where, amidst shrubs and thick plantations, stands the Castle of Kasr-en-Nusha. A division of infantry greeted us with a blast of horns.

The charming abode which the Viceroy had with the greatest kindness offered to us is a castle consisting of two square buildings. A gallery with large glazed windows over the entrance gate unites the two blocks; without and within everything is European, but the variety of the decorations, the gay hangings, the Eastern bath-rooms, and innumerable small details remind one at every turn that one is in the East.

We settled ourselves quickly, and were drinking in with delight the first impressions of Oriental life. The arrangement of the apartments, as well as the numerous charming terraces, the perfume of the flower garden, and the soft delicious air, reminded us of all the glories with which Eastern fancy adorns its tales. After a hasty breakfast some of our party went out hunting with Baron Saurma.

The town had to be traversed, and so we came once more across the canal, and drove through the European quarter, with its broad streets and the handsome houses and rich gardens of the wealthy. We saw from afar the entrance of the Arab quarter. The wild confusion of the streets amused us—European carriages, miserable droskies, donkeys for riding and for draft, mules, camels, rich and poor, beggars and gay Eastern folk, genuine Islamites and half-European Levantines; and besides all this the great crowd of Western folk—tourists, and the like. Passing Kasr-en-Nil we soon reached, driving across the bridge, the dykes and avenues which run between all the great gardens opposite to the city.

Near Tussum Pasha's castle, surrounded by canals and water-meadows, are extensive sugar-cane plantations. In one of these we proposed to hunt. Prince Taxis and the brother of Baron Saurma were on the spot waiting for us. The guns were placed and the dogs loosed.

For a long time the dachshunds seemed to find no scent; at last the chase began; a loud yelping approached the border of the field. Unluckily the wolf left his hiding at a spot where no gun was posted, and so we crossed a broad canal to another plantation. The dogs were let loose once more, but we were soon compelled to desist from our sport by the melancholy discovery, made while the dogs were driving the game, that the cutting of the sugar-cane had commenced on one side of the field.

Numerous labourers—very poor and scantily clad fellaheen, though some of them of most striking appearance— were working under the direction of an overseer robed in long full garments, and wielding a scourge made of thongs of rhinoceros hide. This worthy approached me with much dignity, and made a long speech accompanied with much gesticulation. I made out with some difficulty that he desired that I should leave the ground.

*

* *

* * *

* *

* * *

In the Muski we hired asses—those little skinny beasts which with the high Arab saddle ply by thousands from one end of Cairo to the other and take the place of cabs. In a quick ambling trot, alternating with a gallop, the unwearied donkey driver running after, we rode down the length of the Muski and through the European quarter, across the Canal-el-Ismailiye, to the Schubra Avenue, and back to the Palace Kasr-en-Nusha.

After a short stay we drove to the Viceroy to pay our first but not yet our official visit. The palace in which the Viceroy passes the working hours of the day lies on the western side of the modern town, and is a large, completely European building, wholly devoid of character or style.

The Viceroy received us in a most friendly manner— according to the Eastern custom, excellent coffee was served in bewitching little Turkish cups, and chibouks were smoked.

The visit was soon over, and we took our further way through the European, and then again through native Arab quarters, to the Mosque Sultan Hassam, which stands near the citadel. It is a large, ancient, but alas! very neglected building—by far the most beautiful mosque, and built in the purest Arab style, of all which I saw in Cairo. The tomb of the Sultan, the bathing cisterns, the praying-places, and the pillared halls are all, sad to say, gone to ruin. On the flags the blood-stains from the days of the first massacre of janissaries in 1351 are still shown.

We drove hence by the shortest way home, to take a hasty breakfast and start once more, this time with four horses and postilions, on an expedition to the Pyramids. […]

At the extensive buildings of Kasr-en-Nil we crossed the holy river and the island of Geziret-Bulak, drove past some vice-regal villas and splendid gardens, and soon reached the dyke on which the high-road, fenced in by trees, leads straight through the cultivated land, between fields and the still half-flooded meadows, past a wretched Arab village to the edge of the desert.

The carriage drove some hundred paces on the yellow sand of the Libyan desert, and stopped at the base of the gigantic structures which have looked down for thousands of years on the history of the world. A peculiar awe overcomes each traveller who gazes for the first time in near proximity on these monuments of a long bygone age, and can touch with his hands the stones which centuries before the days of Abraham were piled on this spot, where they now stand, by the labour and the skill of man.

To describe the Pyramids of Ghizeh would be to repeat a task already done over and over again. They belong to the domain of guide-books and the most beaten tracks of travellers. The tombs of dynasties of hoar antiquity have sunk to the level of a Rigi, and the insignificant names of the Western tourist desecrate the venerable stones.

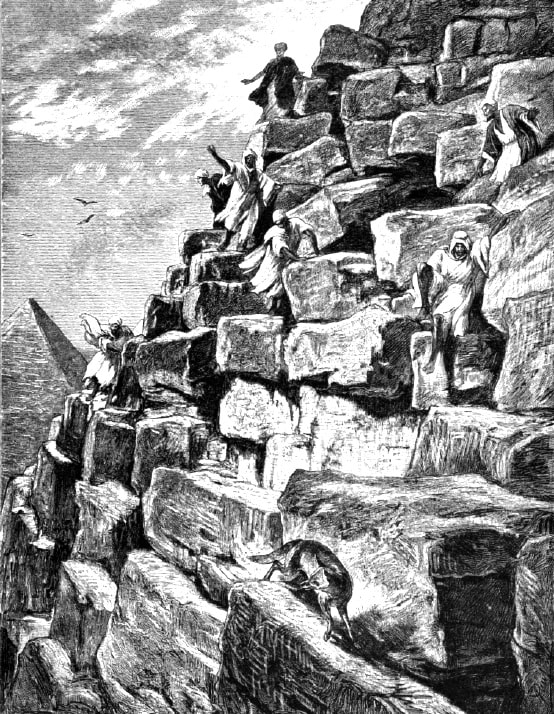

We viewed the Cheops, Chefren, and Menkeri Pyramids, and also the Sphinx with its body half buried by the sands of the desert, and then some Arabs were set to climb the second pyramid, to dislodge the jackals which house there. Unfortunately we were badly placed, and so two jackals escaped unharmed and betook themselves to the boundless desert, intersected by vales and hills. Several shots were fired from below at the beasts as they came down, hopping with extraordinary agility among the stones, but none took effect, as the distance was too great.

The Pyramids gave me, especially when men or animals were climbing upon them, the impression of being great artificially constructed mountains rather than architectural monuments.

After a short stay we drove to the Viceroy to pay our first but not yet our official visit. The palace in which the Viceroy passes the working hours of the day lies on the western side of the modern town, and is a large, completely European building, wholly devoid of character or style.

The Viceroy received us in a most friendly manner— according to the Eastern custom, excellent coffee was served in bewitching little Turkish cups, and chibouks were smoked.

The visit was soon over, and we took our further way through the European, and then again through native Arab quarters, to the Mosque Sultan Hassam, which stands near the citadel. It is a large, ancient, but alas! very neglected building—by far the most beautiful mosque, and built in the purest Arab style, of all which I saw in Cairo. The tomb of the Sultan, the bathing cisterns, the praying-places, and the pillared halls are all, sad to say, gone to ruin. On the flags the blood-stains from the days of the first massacre of janissaries in 1351 are still shown.

We drove hence by the shortest way home, to take a hasty breakfast and start once more, this time with four horses and postilions, on an expedition to the Pyramids. […]

At the extensive buildings of Kasr-en-Nil we crossed the holy river and the island of Geziret-Bulak, drove past some vice-regal villas and splendid gardens, and soon reached the dyke on which the high-road, fenced in by trees, leads straight through the cultivated land, between fields and the still half-flooded meadows, past a wretched Arab village to the edge of the desert.

The carriage drove some hundred paces on the yellow sand of the Libyan desert, and stopped at the base of the gigantic structures which have looked down for thousands of years on the history of the world. A peculiar awe overcomes each traveller who gazes for the first time in near proximity on these monuments of a long bygone age, and can touch with his hands the stones which centuries before the days of Abraham were piled on this spot, where they now stand, by the labour and the skill of man.

To describe the Pyramids of Ghizeh would be to repeat a task already done over and over again. They belong to the domain of guide-books and the most beaten tracks of travellers. The tombs of dynasties of hoar antiquity have sunk to the level of a Rigi, and the insignificant names of the Western tourist desecrate the venerable stones.

We viewed the Cheops, Chefren, and Menkeri Pyramids, and also the Sphinx with its body half buried by the sands of the desert, and then some Arabs were set to climb the second pyramid, to dislodge the jackals which house there. Unfortunately we were badly placed, and so two jackals escaped unharmed and betook themselves to the boundless desert, intersected by vales and hills. Several shots were fired from below at the beasts as they came down, hopping with extraordinary agility among the stones, but none took effect, as the distance was too great.

The Pyramids gave me, especially when men or animals were climbing upon them, the impression of being great artificially constructed mountains rather than architectural monuments.

The sun went down and the landscape floated in a sea of the most glorious light, the grey stones of the Pyramids glowed like gold, and the Valley of the Nile, the mass of houses of Cairo, the citadel, and the towering Mokattam mountains beyond were dyed in crimson hues. We had to hasten home, and drove quickly back by the road by which we had come. […]

Next morning we drove through great part of the European city on our way to the Bulak Museum, on the southern point of the island of Bulak.

The museum is one of the richest and most famous collections of Egyptian antiquities, and in the spacious-well, arranged buildings are stored the priceless treasures of the ancient times of the Pharaohs. A Frenchman is director, the successor of the well-known but lately deceased Mariette Pasha. The brother of the great Egyptologist, Brugsch Pasha, has also a post here, and pointed out to us the most interesting parts of the collection. To describe the Museum of Bulak would demand, on the one hand, extensive scientific acquirements, and on the other it has already been treated of piece by piece in numerous special treatises.

We looked at everything carefully in the rooms, as well as in the little garden. Some Christian mummies from the early days of Christendom interested me very much, as, until I saw them, I had no idea that mummies of this kind existed. They recall, with their bright, richly decorated apparel and black faces, Byzantine Madonnas. After a lengthened visit we left the museum, and drove home.

We had barely time to get ourselves into our Court dresses, when a Pasha who holds the office of Court Marshal under the Khedive appeared, to escort us on our ceremonial visit to his sovereign.

Next morning we drove through great part of the European city on our way to the Bulak Museum, on the southern point of the island of Bulak.

The museum is one of the richest and most famous collections of Egyptian antiquities, and in the spacious-well, arranged buildings are stored the priceless treasures of the ancient times of the Pharaohs. A Frenchman is director, the successor of the well-known but lately deceased Mariette Pasha. The brother of the great Egyptologist, Brugsch Pasha, has also a post here, and pointed out to us the most interesting parts of the collection. To describe the Museum of Bulak would demand, on the one hand, extensive scientific acquirements, and on the other it has already been treated of piece by piece in numerous special treatises.

We looked at everything carefully in the rooms, as well as in the little garden. Some Christian mummies from the early days of Christendom interested me very much, as, until I saw them, I had no idea that mummies of this kind existed. They recall, with their bright, richly decorated apparel and black faces, Byzantine Madonnas. After a lengthened visit we left the museum, and drove home.

We had barely time to get ourselves into our Court dresses, when a Pasha who holds the office of Court Marshal under the Khedive appeared, to escort us on our ceremonial visit to his sovereign.

*

* *

* * *

* *

* * *

Early on the morning of the 23rd February the whole travelling party gathered in the station of that southern line of railway which leads, not only to Siut, but also has a branch into the province of Fayum. Besides ourselves, the two brothers Saurma also put in an appearance.

Herr Zimmerman had again the goodness to conduct our train, and to accompany us to the last station, Abuskar. Prince Taxis had started the day before, with a dragoman, for the lake of Birket-el-Karun, to pitch our tents and arrange the hunting days.

The line lay at first beside the narrow strip of tilled land which stretches along between the western bank of the river Nile and the desert. The thorough character of Egyptian cultivation was very apparent here—high-pressure tillage confined to a narrow space. Simple fellaheen villages alternated with palm forests, larger than those of Lower Egypt. Townships, one might almost say, of circular dovecotes, built in Arab mode, struck us. Doves are here provided with shelter and protection only for the sake of the valuable guano they afford. Occasionally their eggs and down are made use of. These birds never acquire a domesticated character. In colour and size they are true rock pigeons, and are quite untamed in habits.

The line often approaches the Nile, always on the left bank. To the east the desert mountains advance close to the stream; to the west, on the other hand, lies the wave-like, moving, almost flat, Libyan desert.

The railway passes all the Pyramids, and, in fact, near enough to see them well. At first, the grey heads of Ghizeh appear, the proudest of their race. Next come to view the smaller members, of the family, those of Sakkara. We Europeans are accustomed to see a solitary palm in a hothouse, or on the southern coast of our scantily portioned quarter of the globe. Only in the rustling, far-spreading palm forest has this tree its full significance as the symbol of sunny Africa.

At ten in the morning our train turned from the main line, which follows the course of the Nile to Siut, and took us along a branch-line westward into the bare and barren desert. A railway journey in such a region, so grand and magnificent in its loneliness, is a wonderful thing. […]

We reached Siut very early in the morning while it was still quite dark. Unpleasantly roused from sweet slumbers, we left the carriages, and went on foot, preceded by torch-bearers, down a road very well lighted and tastefully decorated, to the landing-stage of the Nile steamers. Our consular agent, a rich Coptic merchant, had made all these preparations and received us most cordially.

The steamer Feruz, kindly lent to us by the Khedive, lay close to the shore, and an old Egyptian admiral who commanded her awaited the travelling party on the bridge.

We all grew extremely fond of our active and able commander, a pure dark-brown African. Unfortunately, he only spoke a few words of English, in addition to Eastern languages, and so our conversations were often very comic, between the aid of the interpreters and our own well-devised signs.

Brugsch Pasha, the renowned Egyptologist, accompanied us likewise on our voyage up the Nile, and stood, together with Herr Rath (the consular assistant and Eastern scholar to whom we were so much indebted in all our wanderings in the East), on the deck of the large and most comfortably equipped yacht of the Viceroy.

The several cabins were very snug. The last, a large room, was assigned to me; above, on the deck, was a spacious dining-room, in which we also passed our forenoons and hours of study.

Above the deck was a platform covered with canvas, from which one obtained an extensive view. Up there we placed the numerous skins of the beasts and birds we had captured, and there, too, we rigged up a workshop for the skin-dresser and his affairs.

On this charming vessel we were to pass a succession of glorious never-to-be-forgotten days. On the yellow waters of the old historic stream, we traversed the land on which rests the magic charm of a thousand years of ancient civilization—where, amidst scenes of the utmost beauty, lofty mountains, majestic deserts, and luxuriant gardens, the most ancient monuments of the world's history lift their grey indestructible summits.

A voyage on the Nile is indisputably one of the most beautiful which can be undertaken, and the richest in picturesque, historic, and ethnographic interest and acquisition. If the Pyramids of Ghizeh and the Egyptian antiquities in the neighbourhood of Cairo enchant the traveller and stimulate inquiry, they are but a foretaste of the rich treasures which Upper Egypt offers.

In the vast halls of the temples, the mysterious crypts, and labyrinthine tombs stretching into the rocks, we look upon the records of the social and political existence of a people who flourished thousands of years ago, attaining power and true culture. Yonder walls are adorned with the hieroglyphical inscriptions which unfold the tale of the days of the Pharaohs. […] In a chamber, formerly carefully closed, in the tomb of Seti I. (circa 1350 B.C.) we saw the likeness of the so-called cow of heaven. Beside it is a long and highly important hieroglyphical inscription, relating to the annihilation of the race of man and the reconstruction of a new order of the world, which supplies the key to a right understanding of the ancient Egyptian theogony.

The translation of this mysterious record is as follows: “There was a king of Upper and Lower Egypt, the Light-god Ra, the god who is Being itself. Whilst he reigned as king men and gods were united. And men began to devise wiles against the Light-god Ra, in order to be rid of him. For his royal majesty had grown old. His bones were of silver, his flesh of gold, his hair of pure sapphire. And his royal majesty saw how he was mocked of men. And his royal majesty spoke to those who were his servants: ‘Call hither to me my eye and the Cloud-god Shu, the Rain-goddess Tafnut, the Earth-god Keb, the Sky-goddess Nut, and at the same time the father and mother who were united with me at such time as I found myself in the primordial waters, and likewise also him who bore my godhead in himself, the god of the primordial water, Nun. Let him bring his retinue with him. Say unto him, “Bring them hither, and tarry not. Look not at the men, and turn not their souls away. Come to the Palace of Heliopolis, together with the gods, who gave their consent that I should betake myself from the water-source to the place which I now occupy.”‘ And the gods were brought. And the gods cast themselves on either side of him to the ground, to do their homage to his majesty, that he might say his sayings before the father of the oldest gods, who had made men and begotten the nobles. And they spake thus to his majesty: ‘Speak to us that we may understand.’

“And the Light-god Ra spoke to the god of the primordial water, Nun, ‘Thou eldest god, out of whom I became, and ye primordial godheads, hear ye now. The men who were made out of my eye, they speak against me. Say—what would ye do? Verily, I will wait, and will not destroy them until I have heard your saying about it.’

“And the majesty of the primordial water, Nun, spake and said, ‘My son, thou Light-god Ra, thou god who art higher than him that is thy father, and greater than him who begat thee, where abide the men who speak such words against thee? For great will be the terror of those who devise wiles against thee, being beside thee, because thine eye is turned upon them.’

“And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said, ‘Go to, they have fled to the mountain, because their soul was full of dread because of my nearness.’

“And the other godheads spake to his majesty: ‘Send out thine eye. Let it. strike for thee those who have devised wiles after the manner of evil-doers, and have not gone out up the stream thither whither thou wouldest.’

“And the Light-god Ra sent forth his eye, and it descended in the form of the goddess Hathor; and this goddess returned after she had destroyed the men upon the mountains.

“And the majesty of this god spake: ‘Be welcome, for thou hast accomplished that which had to be accomplished. The men are fallen to destruction.’

“And this goddess spake and said, ‘I swear by thee that I have executed judgment on the men, and that it was good to my soul.’

“And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said, ‘I will execute judgment on men through thee in the future in that I make them miserable.’

“This is the origin of the name of the Goddess of Violence, Sokhet. The changing night rolled on, and they trod on the blood-streams of the men of the town of Herakleopolis, who had been destroyed. And the majesty of this god spake and said, ‘Call me hither messengers quick and swift; shadows with bodies.’ And when the messengers were forthwith brought unto him, the majesty of this god said that they should go to the town of Elephantine and bring him the fruit of the mandrake in great abundance.

“And the fruits of mandrakes were brought unto him, and they were delivered to the miller who abides in the town of On, that he might grind the fruits of the mandrake. And behold, maidens also were there, who spread out the corn for the preparing of beer, and there were the fruits of the mandrake in the pitchers shaken in and mixed with the blood of men, and seven thousand pitchers of beer were prepared from it.

“And then came the king’s majesty of Upper and Lower Egypt, the Light-god Ra, in company of the other divinities, to look at the beer. And behold the earth was bright, and none of the men had been destroyed by the goddess, who had gone up the stream at the appointed time. And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said, ‘These are the good. I will therefore be the protector of these men.’ And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said, ‘Bear with the hand those pitchers to the place where the goddess has made a massacre among the men.’

“And the majesty of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, the Light-god Ra, gave light during a whole night, to let those beer pitchers be poured out. And the fields in all the four quarters of heaven were flooded with the moisture, according to the will of the majesty of this god.

“And the goddess went out in the early morning. And when she found the fields overflowed her countenance was glad. She drank, and her soul rejoiced; but she did not know that the drink was the blood of men.

“And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said to this goddess, ‘Welcome thou Palm’ (hence the origin of the merry maidens in the Palm city, i.e. Marea at the lake of the name near Alexandria).

“And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said to this goddess, ‘ There should be consecrated to her, at the new year, pitchers to the number of the maidens’ (who had brewed the beer). This is the origin of the consecration of the beer pitchers according to the number of the maids at the feast of Hathor, which is celebrated by all men on the first of the year.

“And the majesty of the Light-god Ra spake to this goddess, ‘Does not sickness arise through the hot breath of a sick person?’ This is the origin of the saying, ‘the sick man has renewed his youth’ (i.e. has infected another).

“And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said, ‘As I live my soul is weary of being with men. I have destroyed them, and there is none that remains. Not short, but long has been my arm.’

“And the divinities who were in his train said, ‘ Go not hence because of thy weariness, for thou hast the power to do as pleaseth thee.’

“And the majesty of this god spake to the majesty of the god of the primordial water, Nun,’ My body will increase in weakness which has now begun, unless I go where none other can reach to me.’

“And the majesty of the primordial water, Nun, said, ‘The son of the Cloud-god Shu shall be a stay to his father through his labours ; and the daughter, the Sky-goddess Nut, shall go to the heights to bear her father.’

“And the Sky-goddess Nut said, ‘How shall that be, O thou my father, and thou god of the primordial water, Nun?’

“Thus the Sky-goddess Nut spake before her father to the god of the primordial water, Nun. Then was the Sky-goddess Nut changed into a great cow, on the back of which the majesty of the Light-god Ra might be carried.

“After the men who had gone up the stream knew what had happened, they stood and looked at him as he sat on the back of the cow.

“And the men spake and said to him, ‘Thou Light-god Ra, forsake us not; we will slay thine enemies which have devised wiles against thee. They shall be slain.’

“His majesty went in into his palace, but those who followed him remained with the men so long as the earth lay in darkness. But when the earth grew light and morning rose, the men came forth armed with bows and lances, and shot at the adversaries of the god. And the majesty of this god said, ‘Your sins are forgiven, the victims are slaughtered.’ (This is the origin of the slaughter-sacrifice.) And this god spake to the heavenly goddess Nut, ‘I have laid myself on my back, raise me up.’ She understood the meaning, and the heavenly goddess Nut stretched herself out. This is the origin of the phrase, ‘lay thyself on thy back, stretch thyself.’

“And the majesty of this god said, ‘Now have I departed from men. I have gone up and held my survey.’

“And the majesty of this god held his survey from within outwards. And he said, ‘Seek for me strong bearers in the form of a mass of men.’ This is the origin of the phrase ‘mass of men.’

“And his royal majesty said, ‘How peacefully does a broad field spread out.’ This is the origin of the name ‘field of peace.’ ‘I will pluck herbs in it;’ hence the origin of the name ‘Pluckfield.’ ‘I will provide the inhabitants with all things.’ This is the origin of the name of ‘the thing-star’ among the stars.

“And the heavenly goddess Nut trembled because she was so high up. And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said, ‘I have devised bearers to support her;’ hence the origin of supporting bearers (i.e. Karyatides).

“And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said, ‘My son, thou Cloud-god Ra, place thyself beneath my daughter, the Sky-goddess Nut. Be to me the guardian of the supporting bearers who dwell in darkness.

Take thou the heavenly goddess on thy head and be her guardian.’ This is the origin of the tendance of a daughter’s son, and the origin of the custom of a father putting his son on his head.”

The following statement has been communicated respecting the cow, i.e. a description of the picture: the supporting bearers, “the mass of men,” stand before her shoulder-blade, supporting bearers upon her back, which is painted over in all directions with bright colours.

On the belly are nine stars. The figure of the god Set is behind — another image of the same beside the legs. The Cloud-god Shu stands under the belly, made of strong stone. His two arms bear the stars. The inscription containing his name between the arms is—"The Cloud-god Shu himself.”

A ship stands there. Oars and a small temple are in it, and above it the disc of the sun. The Light-god Ra stands in it in front of the Cloud god Shu, and by his hand; another reading is, “behind him beside his hand.”

The udders of the cow are placed in the middle by its left leg.

The surfaces of the cow are covered with inscriptions; those towards the middle of the hind leg are—” The outer heavens,” and “ I am where I am,” and “I do not let her turn back.” The inscription below the ship, which stands in front, is, “Rest not, my son.”

Those which are written in the opposite direction run, “Thy bearing is life-like;” another, “The eternal is expressed therein,” and “Thy son is yonder;” another, “Life, happiness, and health be granted to these thy nostrils.”

The inscription behind the Cloud-god Shu, by his arms, is, “Her guardian;” that which is behind him, by his feet, and written in the opposite direction, is, “The truth;” another, “They enter in;” and another, “I am the daily protector.”

The inscription which is under the arm of the figure which stands beneath and behind the left leg runs, “The closer up of all things.”

That which stands over the head of the figure at the hind quarters of the cow and near its legs is, “Guardian of her going out.”

That which is behind the two figures who stand at the cow’s leg, and is written above their heads, runs, “The old man who sings praises at his going out,” and “The old man who adores at his coming in.”

The inscriptions over the heads of the two figures which stand between the fore legs of the cow are “Listener,” “Hearer,” and “Sceptre of the heavenly height.”

“And the majesty of this god said to the god Thot (god of understanding), ‘Call me hither the majesty of the Earth-god Keb with the words, “Come and set forth at once.”

“And the majesty of the Earth-god Keb came, and the majesty of the Light-god Ra said, ‘There has been a battle because of thy worms (i.e. of men) which tarry for thee. It will be for their weal that they fear me as long as I exist. Thereby shalt thou know their virtue. Make thee ready and go where my father the god of the primordial water, Nun, abides. Say to him--

“‘“Preserve the worms on the earth and in the water.” Make forthwith writings for every zone in which thy worms dwell, saying, “Your keeper is he who embraces all things.” If they shall know that I have gone far away, it is for their weal that I should rise upon them as the light of the sun. A healing is needful. It is the father whom they need. Be thou the father on this ever-during earth.

“‘Also they shall be shielded because of their wise thoughts, and the judgment of their mouth shall be to their salvation, for my own wisdom is contained therein as salvation. Who has acknowledged them shall be safe, for my protection will be given to none because of the greatness which has been given him before me.

“I will unite them to thy son Osiris, and will preserve their children (to the astonishment of their princes), whose virtues are such that they have acted according to their love to the whole world, and according to the wise thoughts which dwelt within them.’

“And the majesty of this god said, ‘Call me the god Thot’ (of understanding), and he was called. And the majesty of this god said to Thot, ‘Behold! great is the distance from heaven, where I have set up my throne, and where I must dwell to dispense the light of the sun. Thou glorious god, in the deep, and in the world of tombs, where thou art scribe, and punishest those who dwell there, and whose acts and deeds have been of sin, thereby that thou keepest far from me those who followed evil—which fills my heart with shame — be thou in my place, my representative, or wherefore art thou called Thot, the representative of the sun? I will bid thee send the princes (in thy name).” This is the origin of Ibis, i.e. the messenger bird of Thot. ‘I will let thee stretch thine hand to the face of the ancient gods, who are greater than thou. It will be well if thou stillest my thirst.’ This is the origin of the water-bird of Thot. ‘I will let thee embrace heaven and earth with thy glory, as a beam of light;’ hence the name of the ‘enfolder’ for the moon. ‘I will let thee drive back all the barbarians;’ hence the name of ‘ the expeller,’ for the dog-headed ape; and this the origin of his office as leader of armies. ‘Be thou, therefore, my representative for all visible things that through thee may be manifested, and all men shall praise thee as God.’

“If any one says this decree to himself, let him rub himself first with oils and ointments, and let him raise the perfuming pan in his hands, backwards, to both his ears.

“Let him wash his mouth with holy soap. Let him put on clean garments.

“Let him cleanse himself with water of the flood. Let his feet be clothed in shining white sandals. An image of the goddess of Truth, painted green, shall lie upon his tongue.

“If it shall please him to say it (the decree) to the god Thot, let him purify himself in a nine-fold purification, three days long.

“In like manner shall the priests and others do. If any man will repeat it, let him observe the following instructions in the use of this piece of writing:--

“Let him take his stand in a circle which separates him from that which is without.

“Let him set his eye upon it and turn all his limbs towards it, and let his feet not go forward. If a man shall so say it, he shall be as the Light-god Ra, on the day of his birth. His goods shall not be minished. Nothing shall go out his house, but shall endure in the right way a million-fold.”

Thus ends the exact description of the heavenly cow and all the mottoes which surround it.

The mystic strain which runs through the dogmas of this religion of thousands of ages past is very interesting, and the gorgeous wealth of description marks these doctrines as belonging to a southern, and especially an Oriental cultus.

Herr Zimmerman had again the goodness to conduct our train, and to accompany us to the last station, Abuskar. Prince Taxis had started the day before, with a dragoman, for the lake of Birket-el-Karun, to pitch our tents and arrange the hunting days.

The line lay at first beside the narrow strip of tilled land which stretches along between the western bank of the river Nile and the desert. The thorough character of Egyptian cultivation was very apparent here—high-pressure tillage confined to a narrow space. Simple fellaheen villages alternated with palm forests, larger than those of Lower Egypt. Townships, one might almost say, of circular dovecotes, built in Arab mode, struck us. Doves are here provided with shelter and protection only for the sake of the valuable guano they afford. Occasionally their eggs and down are made use of. These birds never acquire a domesticated character. In colour and size they are true rock pigeons, and are quite untamed in habits.

The line often approaches the Nile, always on the left bank. To the east the desert mountains advance close to the stream; to the west, on the other hand, lies the wave-like, moving, almost flat, Libyan desert.

The railway passes all the Pyramids, and, in fact, near enough to see them well. At first, the grey heads of Ghizeh appear, the proudest of their race. Next come to view the smaller members, of the family, those of Sakkara. We Europeans are accustomed to see a solitary palm in a hothouse, or on the southern coast of our scantily portioned quarter of the globe. Only in the rustling, far-spreading palm forest has this tree its full significance as the symbol of sunny Africa.

At ten in the morning our train turned from the main line, which follows the course of the Nile to Siut, and took us along a branch-line westward into the bare and barren desert. A railway journey in such a region, so grand and magnificent in its loneliness, is a wonderful thing. […]

We reached Siut very early in the morning while it was still quite dark. Unpleasantly roused from sweet slumbers, we left the carriages, and went on foot, preceded by torch-bearers, down a road very well lighted and tastefully decorated, to the landing-stage of the Nile steamers. Our consular agent, a rich Coptic merchant, had made all these preparations and received us most cordially.

The steamer Feruz, kindly lent to us by the Khedive, lay close to the shore, and an old Egyptian admiral who commanded her awaited the travelling party on the bridge.

We all grew extremely fond of our active and able commander, a pure dark-brown African. Unfortunately, he only spoke a few words of English, in addition to Eastern languages, and so our conversations were often very comic, between the aid of the interpreters and our own well-devised signs.

Brugsch Pasha, the renowned Egyptologist, accompanied us likewise on our voyage up the Nile, and stood, together with Herr Rath (the consular assistant and Eastern scholar to whom we were so much indebted in all our wanderings in the East), on the deck of the large and most comfortably equipped yacht of the Viceroy.

The several cabins were very snug. The last, a large room, was assigned to me; above, on the deck, was a spacious dining-room, in which we also passed our forenoons and hours of study.

Above the deck was a platform covered with canvas, from which one obtained an extensive view. Up there we placed the numerous skins of the beasts and birds we had captured, and there, too, we rigged up a workshop for the skin-dresser and his affairs.

On this charming vessel we were to pass a succession of glorious never-to-be-forgotten days. On the yellow waters of the old historic stream, we traversed the land on which rests the magic charm of a thousand years of ancient civilization—where, amidst scenes of the utmost beauty, lofty mountains, majestic deserts, and luxuriant gardens, the most ancient monuments of the world's history lift their grey indestructible summits.

A voyage on the Nile is indisputably one of the most beautiful which can be undertaken, and the richest in picturesque, historic, and ethnographic interest and acquisition. If the Pyramids of Ghizeh and the Egyptian antiquities in the neighbourhood of Cairo enchant the traveller and stimulate inquiry, they are but a foretaste of the rich treasures which Upper Egypt offers.

In the vast halls of the temples, the mysterious crypts, and labyrinthine tombs stretching into the rocks, we look upon the records of the social and political existence of a people who flourished thousands of years ago, attaining power and true culture. Yonder walls are adorned with the hieroglyphical inscriptions which unfold the tale of the days of the Pharaohs. […] In a chamber, formerly carefully closed, in the tomb of Seti I. (circa 1350 B.C.) we saw the likeness of the so-called cow of heaven. Beside it is a long and highly important hieroglyphical inscription, relating to the annihilation of the race of man and the reconstruction of a new order of the world, which supplies the key to a right understanding of the ancient Egyptian theogony.

The translation of this mysterious record is as follows: “There was a king of Upper and Lower Egypt, the Light-god Ra, the god who is Being itself. Whilst he reigned as king men and gods were united. And men began to devise wiles against the Light-god Ra, in order to be rid of him. For his royal majesty had grown old. His bones were of silver, his flesh of gold, his hair of pure sapphire. And his royal majesty saw how he was mocked of men. And his royal majesty spoke to those who were his servants: ‘Call hither to me my eye and the Cloud-god Shu, the Rain-goddess Tafnut, the Earth-god Keb, the Sky-goddess Nut, and at the same time the father and mother who were united with me at such time as I found myself in the primordial waters, and likewise also him who bore my godhead in himself, the god of the primordial water, Nun. Let him bring his retinue with him. Say unto him, “Bring them hither, and tarry not. Look not at the men, and turn not their souls away. Come to the Palace of Heliopolis, together with the gods, who gave their consent that I should betake myself from the water-source to the place which I now occupy.”‘ And the gods were brought. And the gods cast themselves on either side of him to the ground, to do their homage to his majesty, that he might say his sayings before the father of the oldest gods, who had made men and begotten the nobles. And they spake thus to his majesty: ‘Speak to us that we may understand.’

“And the Light-god Ra spoke to the god of the primordial water, Nun, ‘Thou eldest god, out of whom I became, and ye primordial godheads, hear ye now. The men who were made out of my eye, they speak against me. Say—what would ye do? Verily, I will wait, and will not destroy them until I have heard your saying about it.’

“And the majesty of the primordial water, Nun, spake and said, ‘My son, thou Light-god Ra, thou god who art higher than him that is thy father, and greater than him who begat thee, where abide the men who speak such words against thee? For great will be the terror of those who devise wiles against thee, being beside thee, because thine eye is turned upon them.’

“And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said, ‘Go to, they have fled to the mountain, because their soul was full of dread because of my nearness.’

“And the other godheads spake to his majesty: ‘Send out thine eye. Let it. strike for thee those who have devised wiles after the manner of evil-doers, and have not gone out up the stream thither whither thou wouldest.’

“And the Light-god Ra sent forth his eye, and it descended in the form of the goddess Hathor; and this goddess returned after she had destroyed the men upon the mountains.

“And the majesty of this god spake: ‘Be welcome, for thou hast accomplished that which had to be accomplished. The men are fallen to destruction.’

“And this goddess spake and said, ‘I swear by thee that I have executed judgment on the men, and that it was good to my soul.’

“And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said, ‘I will execute judgment on men through thee in the future in that I make them miserable.’

“This is the origin of the name of the Goddess of Violence, Sokhet. The changing night rolled on, and they trod on the blood-streams of the men of the town of Herakleopolis, who had been destroyed. And the majesty of this god spake and said, ‘Call me hither messengers quick and swift; shadows with bodies.’ And when the messengers were forthwith brought unto him, the majesty of this god said that they should go to the town of Elephantine and bring him the fruit of the mandrake in great abundance.

“And the fruits of mandrakes were brought unto him, and they were delivered to the miller who abides in the town of On, that he might grind the fruits of the mandrake. And behold, maidens also were there, who spread out the corn for the preparing of beer, and there were the fruits of the mandrake in the pitchers shaken in and mixed with the blood of men, and seven thousand pitchers of beer were prepared from it.

“And then came the king’s majesty of Upper and Lower Egypt, the Light-god Ra, in company of the other divinities, to look at the beer. And behold the earth was bright, and none of the men had been destroyed by the goddess, who had gone up the stream at the appointed time. And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said, ‘These are the good. I will therefore be the protector of these men.’ And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said, ‘Bear with the hand those pitchers to the place where the goddess has made a massacre among the men.’

“And the majesty of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, the Light-god Ra, gave light during a whole night, to let those beer pitchers be poured out. And the fields in all the four quarters of heaven were flooded with the moisture, according to the will of the majesty of this god.

“And the goddess went out in the early morning. And when she found the fields overflowed her countenance was glad. She drank, and her soul rejoiced; but she did not know that the drink was the blood of men.

“And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said to this goddess, ‘Welcome thou Palm’ (hence the origin of the merry maidens in the Palm city, i.e. Marea at the lake of the name near Alexandria).

“And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said to this goddess, ‘ There should be consecrated to her, at the new year, pitchers to the number of the maidens’ (who had brewed the beer). This is the origin of the consecration of the beer pitchers according to the number of the maids at the feast of Hathor, which is celebrated by all men on the first of the year.

“And the majesty of the Light-god Ra spake to this goddess, ‘Does not sickness arise through the hot breath of a sick person?’ This is the origin of the saying, ‘the sick man has renewed his youth’ (i.e. has infected another).

“And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said, ‘As I live my soul is weary of being with men. I have destroyed them, and there is none that remains. Not short, but long has been my arm.’

“And the divinities who were in his train said, ‘ Go not hence because of thy weariness, for thou hast the power to do as pleaseth thee.’

“And the majesty of this god spake to the majesty of the god of the primordial water, Nun,’ My body will increase in weakness which has now begun, unless I go where none other can reach to me.’

“And the majesty of the primordial water, Nun, said, ‘The son of the Cloud-god Shu shall be a stay to his father through his labours ; and the daughter, the Sky-goddess Nut, shall go to the heights to bear her father.’

“And the Sky-goddess Nut said, ‘How shall that be, O thou my father, and thou god of the primordial water, Nun?’

“Thus the Sky-goddess Nut spake before her father to the god of the primordial water, Nun. Then was the Sky-goddess Nut changed into a great cow, on the back of which the majesty of the Light-god Ra might be carried.

“After the men who had gone up the stream knew what had happened, they stood and looked at him as he sat on the back of the cow.

“And the men spake and said to him, ‘Thou Light-god Ra, forsake us not; we will slay thine enemies which have devised wiles against thee. They shall be slain.’

“His majesty went in into his palace, but those who followed him remained with the men so long as the earth lay in darkness. But when the earth grew light and morning rose, the men came forth armed with bows and lances, and shot at the adversaries of the god. And the majesty of this god said, ‘Your sins are forgiven, the victims are slaughtered.’ (This is the origin of the slaughter-sacrifice.) And this god spake to the heavenly goddess Nut, ‘I have laid myself on my back, raise me up.’ She understood the meaning, and the heavenly goddess Nut stretched herself out. This is the origin of the phrase, ‘lay thyself on thy back, stretch thyself.’

“And the majesty of this god said, ‘Now have I departed from men. I have gone up and held my survey.’

“And the majesty of this god held his survey from within outwards. And he said, ‘Seek for me strong bearers in the form of a mass of men.’ This is the origin of the phrase ‘mass of men.’

“And his royal majesty said, ‘How peacefully does a broad field spread out.’ This is the origin of the name ‘field of peace.’ ‘I will pluck herbs in it;’ hence the origin of the name ‘Pluckfield.’ ‘I will provide the inhabitants with all things.’ This is the origin of the name of ‘the thing-star’ among the stars.

“And the heavenly goddess Nut trembled because she was so high up. And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said, ‘I have devised bearers to support her;’ hence the origin of supporting bearers (i.e. Karyatides).

“And the majesty of the Light-god Ra said, ‘My son, thou Cloud-god Ra, place thyself beneath my daughter, the Sky-goddess Nut. Be to me the guardian of the supporting bearers who dwell in darkness.

Take thou the heavenly goddess on thy head and be her guardian.’ This is the origin of the tendance of a daughter’s son, and the origin of the custom of a father putting his son on his head.”

The following statement has been communicated respecting the cow, i.e. a description of the picture: the supporting bearers, “the mass of men,” stand before her shoulder-blade, supporting bearers upon her back, which is painted over in all directions with bright colours.

On the belly are nine stars. The figure of the god Set is behind — another image of the same beside the legs. The Cloud-god Shu stands under the belly, made of strong stone. His two arms bear the stars. The inscription containing his name between the arms is—"The Cloud-god Shu himself.”

A ship stands there. Oars and a small temple are in it, and above it the disc of the sun. The Light-god Ra stands in it in front of the Cloud god Shu, and by his hand; another reading is, “behind him beside his hand.”

The udders of the cow are placed in the middle by its left leg.

The surfaces of the cow are covered with inscriptions; those towards the middle of the hind leg are—” The outer heavens,” and “ I am where I am,” and “I do not let her turn back.” The inscription below the ship, which stands in front, is, “Rest not, my son.”

Those which are written in the opposite direction run, “Thy bearing is life-like;” another, “The eternal is expressed therein,” and “Thy son is yonder;” another, “Life, happiness, and health be granted to these thy nostrils.”

The inscription behind the Cloud-god Shu, by his arms, is, “Her guardian;” that which is behind him, by his feet, and written in the opposite direction, is, “The truth;” another, “They enter in;” and another, “I am the daily protector.”

The inscription which is under the arm of the figure which stands beneath and behind the left leg runs, “The closer up of all things.”

That which stands over the head of the figure at the hind quarters of the cow and near its legs is, “Guardian of her going out.”

That which is behind the two figures who stand at the cow’s leg, and is written above their heads, runs, “The old man who sings praises at his going out,” and “The old man who adores at his coming in.”

The inscriptions over the heads of the two figures which stand between the fore legs of the cow are “Listener,” “Hearer,” and “Sceptre of the heavenly height.”

“And the majesty of this god said to the god Thot (god of understanding), ‘Call me hither the majesty of the Earth-god Keb with the words, “Come and set forth at once.”

“And the majesty of the Earth-god Keb came, and the majesty of the Light-god Ra said, ‘There has been a battle because of thy worms (i.e. of men) which tarry for thee. It will be for their weal that they fear me as long as I exist. Thereby shalt thou know their virtue. Make thee ready and go where my father the god of the primordial water, Nun, abides. Say to him--

“‘“Preserve the worms on the earth and in the water.” Make forthwith writings for every zone in which thy worms dwell, saying, “Your keeper is he who embraces all things.” If they shall know that I have gone far away, it is for their weal that I should rise upon them as the light of the sun. A healing is needful. It is the father whom they need. Be thou the father on this ever-during earth.

“‘Also they shall be shielded because of their wise thoughts, and the judgment of their mouth shall be to their salvation, for my own wisdom is contained therein as salvation. Who has acknowledged them shall be safe, for my protection will be given to none because of the greatness which has been given him before me.

“I will unite them to thy son Osiris, and will preserve their children (to the astonishment of their princes), whose virtues are such that they have acted according to their love to the whole world, and according to the wise thoughts which dwelt within them.’

“And the majesty of this god said, ‘Call me the god Thot’ (of understanding), and he was called. And the majesty of this god said to Thot, ‘Behold! great is the distance from heaven, where I have set up my throne, and where I must dwell to dispense the light of the sun. Thou glorious god, in the deep, and in the world of tombs, where thou art scribe, and punishest those who dwell there, and whose acts and deeds have been of sin, thereby that thou keepest far from me those who followed evil—which fills my heart with shame — be thou in my place, my representative, or wherefore art thou called Thot, the representative of the sun? I will bid thee send the princes (in thy name).” This is the origin of Ibis, i.e. the messenger bird of Thot. ‘I will let thee stretch thine hand to the face of the ancient gods, who are greater than thou. It will be well if thou stillest my thirst.’ This is the origin of the water-bird of Thot. ‘I will let thee embrace heaven and earth with thy glory, as a beam of light;’ hence the name of the ‘enfolder’ for the moon. ‘I will let thee drive back all the barbarians;’ hence the name of ‘ the expeller,’ for the dog-headed ape; and this the origin of his office as leader of armies. ‘Be thou, therefore, my representative for all visible things that through thee may be manifested, and all men shall praise thee as God.’

“If any one says this decree to himself, let him rub himself first with oils and ointments, and let him raise the perfuming pan in his hands, backwards, to both his ears.

“Let him wash his mouth with holy soap. Let him put on clean garments.

“Let him cleanse himself with water of the flood. Let his feet be clothed in shining white sandals. An image of the goddess of Truth, painted green, shall lie upon his tongue.

“If it shall please him to say it (the decree) to the god Thot, let him purify himself in a nine-fold purification, three days long.

“In like manner shall the priests and others do. If any man will repeat it, let him observe the following instructions in the use of this piece of writing:--

“Let him take his stand in a circle which separates him from that which is without.

“Let him set his eye upon it and turn all his limbs towards it, and let his feet not go forward. If a man shall so say it, he shall be as the Light-god Ra, on the day of his birth. His goods shall not be minished. Nothing shall go out his house, but shall endure in the right way a million-fold.”

Thus ends the exact description of the heavenly cow and all the mottoes which surround it.

The mystic strain which runs through the dogmas of this religion of thousands of ages past is very interesting, and the gorgeous wealth of description marks these doctrines as belonging to a southern, and especially an Oriental cultus.

*

* *

* * *

* *

* * *

We rode from Memphis, beyond the cultivated land, up into the great Libyan desert, to the Pyramids of Sakkara, and past Mariette’s house to the Apis tombs.

The country here has exactly the same character as that at the Pyramids of Ghizeh. These Pyramids can be seen from those of Sakkara, as well as Cairo, its citadel, and the terraced forms of the Mokattam mountains.

We penetrated, provided with torches, into the subterranean labyrinth of passages of the Apis tombs. They seemed interminable, and the air was dry and oppressive. “In the most brilliant period of Egyptian history, as also later, under the foreign Ptolemean princes, the bulls were placed in gigantic sarcophagi of the hardest stone, and laid in separate compartments of the underground galleries. They are placed in chronological order one after the other, each grave having its own inscription. The Apis tombs of Memphis, which are now made accessible to strangers in the most convenient way, contain twenty-four of these colossal sarcophagi. The series of bulls buried here began with the middle of the sixteenth century B.C., and closed at the time of the Emperor Augustus.

“The animals which lived before that period found resting-places after death in the terraced Pyramid of Sakkara. In its interior there is a large vaulted space with separate passages and niches. The bones of bulls which remain in them distinctly indicate the purpose of this Pyramid.”

We breakfasted in the small house near the Apis tombs which had been built for purposes of study by the famous Egyptologist, Mariette, lately deceased; and then went to the curious low-terraced Pyramid to hunt jackals. The Arabs had scarcely begun to climb the stones when down came a jackal in full flight and was shot by me. After this little sporting interlude we visited the other Pyramids in the neighbourhood, and the small recently opened one of King Pepi I.

Permit me here to quote some notes about Pyramids in general, those of Memphis and Ghizeh, and also about the Sphinx, for which I am indebted to my friend Brugsch.

“The old national god of Memphis, Ptah, in his special capacity of king of the dead and protector of the departed, bore the name of Sokar. In this capacity he was absolutely identical with the god Osiris of the whole country. A sanctuary dedicated to him on the site of the present village of Sakkara bore the old Egyptian designation ‘house of Sokar,’ from which the Arabic name of the village Sakkara is directly derived. The graves of the Memphites, which are grouped round the Pyramids in regular order, and the oldest of which belong to the period of the Memphite kings, were under the protection of this king of the dead. A whole city of the dead arose on the soil of the desert. Long rows of funeral chapels built in stone, the so-called ‘houses of eternity,’ formed by their continuity the streets of the city. Underneath them, in deep shafts, were the actual chambers in which the departed rested in their wooden or stone coffins. The best-preserved mausoleum of the times of the Memphite kings is that of a certain distinguished Egyptian named Thi. He lived in the middle of the fourth century B.C., and prepared a chapel for himself in the vicinity of the Pyramids of those kings under whose sway he had held his post of officer of state.

“The richly coloured, delicate, and carefully executed pictures on the walls of this mortuary have a high value from the multitude of the scenes from life which they place before our eyes in the most vivid way—the agriculture and industries, as well as the sacrificial rites, of these remotest periods of human history.

“These pictures owe their existence to the belief that in the world beyond, the earthly goods of a wealthy and distinguished landowner would still belong to the departed. Navigation, cattle-breeding, agriculture, the overflow of the Nile, the handicrafts from the cobbler to the joiner, painting and sculpture, and, to crown all, administration down to the humblest clerk; nothing is forgotten to give to the pictures the impress of the most life-like exactitude. The wife and children take a prominent place in these scenes. The first is especially favoured with the most flattering qualities, which culminate in the expression, ‘ Her beauty was proverbial, and sweet was her gentleness to her husband.’”

In the cities of the dead of Memphis, which extend in unbroken succession from Abu-roash to Fayum, the old graves of the Memphite kings rose visible from afar at the edge of the desert plateau. These kings ruled in Egypt from B.C. 4000 to B.C. 2500. Although a large number of these tombs have ere now been levelled to the ground, those that remain are amply sufficient to enable us to form a correct judgment as to their style of building, and the mode of its execution. The grave-chamber has mostly a pointed roof formed by two limestone monoliths, which lean against each other, sloping upwards. This must be regarded as the essential point of every pyramid. The covering of limestone blocks piled over it takes the form of a pyramid. The angles of a pyramid were called in old Egyptian Pir-am-us; hence the Greek name Pyramis.

The pyramid was added to according to the length of the reign of the Pharaoh who built it, so that with his advancing age the pyramid grew likewise. The different heights of the Pyramids represent, therefore, the length of the reigns of their royal founders, while their local arrangement following each other from north to south presents to the eye of the spectator their chronological order also.

The entrance to the Pyramids is always turned to the north. The door is blocked by a drop-stone of granite; an oblique and then a level passage terminates in the grave-chamber itself, in which the mummies of the Pharaohs lie on the western side in a sarcophagus which is usually of granite. The stair-like shelves of the Pyramids were filled with stone blocks polished on the outside, and when fitted together appeared as a smooth surface, which presented itself in triangular form from the base to the point as a complete whole.

The greater number of the Pyramids had been opened in early time by treasure-seekers. The Persians under Cambyses, the Romans, the Arabian Caliphs, have all sought for buried treasure. In our days the attempt has been made anew to penetrate the interior of the Pyramids of Sakkara.”

According to Brugsch Pasha we were the first Europeans who had visited the Pyramid of King Pepi since it had been opened.

Even in classical times the three great Pyramids of Ghizeh were reckoned among the wonders of the world, and they still excite the admiration of our own blasé contemporaries. The enormous mass of stone employed in their construction, and its even distribution as provided for in the execution of these gigantic monuments, has not its equal anywhere else. The largest of the three Pyramids was once four hundred and fifty-one feet in height. Its cubic contents are estimated at not less than seventy-five millions of cubic feet. It has been calculated that the stone employed in building it would suffice to put a wall six feet high all round France. The inscriptions name King Chufu, i.e. the Cheops of classical authors, who ruled in Egypt 3700 B.C., as its builder. The Pyramid which his son and successor, Chafra (King Chephres of Greek traditions), erected in a south-westerly direction from that of his predecessor retains its old coating in the upper part.

At its foot there existed a special sanctuary, in form like a temple, and built of blocks of limestone, granite, and alabaster, and which was connected, by a long road leading to the east, with the so-called Temple of the Sphinx. The remains of this road are in almost entire preservation, and have been lately cleared from the sand of the desert. The grounds of the Temple of the Sphinx, in which, at the bottom of a now filled-up well, several statues of King Chafra were discovered, is a point of special attraction to European travellers. But no inscription adorns the granite and alabaster walls of this gigantic structure, and its purpose remains an unsolved riddle. […]

The Sphinx lies with its lower part hidden deep in the sand. The inscriptions give the figure the name of Hu, and describe it as a symbolic embodiment of the Sun-god under his name of Hormachu, i.e. Horus, in the realms of light. The features of the figure, which are unfortunately much damaged, represented those of its royal author.

A long inscription between the outstretched fore feet of the lion's body, now covered in the sand, records a wonderful dream of one of the later Pharaohs of Egyptian history. The last, by name Thutmes IV. (buried circa 1530 B.C.), causes what follows to be related of himself.

“See, he was wont to hunt for his pleasure on the territory of the province of Memphis, southward and northward, where he fired with brazen arrows at the mark, and hunted the lions of the valley of Gazelles. He came here in his chariot, whose horses were fleeter than the wind. With him were two of his servants, and no man knew who they were.

“And behold when the time of rest was come which he granted to his servants, then he employed it to decorate the figure of the Sphinx of the god Hormachu, beside the temple of the god Sohar, at the city of the dead, and the goddess Ranuti by sacrificial gifts of corn and flowers, and to pray to Isis, to her who commands the wall of the north and the wall of the south, and to the goddess Sochet of Xois, and to the god Sutek. For a mighty spell rests from ages past on this venerable spot, and even to the regions which the divinities of Babylon (Old Cairo) inhabit, and where lies the sacred way of the gods, to the west side from Heliopolis. For behold the Sphinx form of the great and lofty god Cheper rests upon this place, and the greatest of the spirits and the most mighty god tarries here. To him all the dwellers in Memphis, and those in all the cities which are in its dominion, lift their hands to worship before his face and to bring him sacrifices.

“One day it befel that Prince Thutmes came here on his journey about the time of midday. And after he had laid himself down in the shadow of this god, sleep laid hold of him. Dreaming in his sleep at the moment that the sun stood in the zenith, it seemed to him as though the majesty of this mighty god spoke to him with his own mouth, as a father speaks with his son while he spake thus: ‘Behold me, and consider me well, thou my son Thutmes. I am thy father Hormachu, the god Cheper-Ra-Tum. The kingdom shall be given to thee; thou shalt wear the crown of Egypt on the throne of the god of the earth Keb ; the whole earth shall belong to thee, in its breadth and length, lighted by the beaming eye of the Lord of all. The riches from the interior of the land, and many tributes from all people, shall belong to thee, and thou shalt rejoice in length of life for many years. The best shall be thy portion, for my face is turned to thee, and my heart belongs to thee. The sand of the desert on which I have my being has covered me up. Answer me, that thou wilt do that which is my wish. Then shall I know that thou art my son and defender. Come nearer, let me be united to thee.’

“Upon this the prince awoke, and what he had just heard was repeated. He understood the word of this god, and kept it to himself in his heart while he thus spake: ‘In very deed I see the dwellers in the temples of the town of Memphis, how they bring sacrifices to this god without doing anything to protect from the sands the work o/ King Chafra, the image which he has set up to the god Tum-Hormachu. ...”

The text is injured here, and has become illegible. The conclusion is nevertheless easy to guess. Thutmes has the Sphinx cleared of sand, and is in consequence crowned King of Egypt. The fact is of small historic value, but all the more interesting is the deduction that even in the sixteenth century B.C. the body of the Sphinx lay as now, half buried in deep sand. […]

After we had scrambled into the Pyramid of King Pepi I. with some pains and difficulty, we left the desert and its ancient monuments and rode back into the cultivated land.

The country here has exactly the same character as that at the Pyramids of Ghizeh. These Pyramids can be seen from those of Sakkara, as well as Cairo, its citadel, and the terraced forms of the Mokattam mountains.

We penetrated, provided with torches, into the subterranean labyrinth of passages of the Apis tombs. They seemed interminable, and the air was dry and oppressive. “In the most brilliant period of Egyptian history, as also later, under the foreign Ptolemean princes, the bulls were placed in gigantic sarcophagi of the hardest stone, and laid in separate compartments of the underground galleries. They are placed in chronological order one after the other, each grave having its own inscription. The Apis tombs of Memphis, which are now made accessible to strangers in the most convenient way, contain twenty-four of these colossal sarcophagi. The series of bulls buried here began with the middle of the sixteenth century B.C., and closed at the time of the Emperor Augustus.

“The animals which lived before that period found resting-places after death in the terraced Pyramid of Sakkara. In its interior there is a large vaulted space with separate passages and niches. The bones of bulls which remain in them distinctly indicate the purpose of this Pyramid.”

We breakfasted in the small house near the Apis tombs which had been built for purposes of study by the famous Egyptologist, Mariette, lately deceased; and then went to the curious low-terraced Pyramid to hunt jackals. The Arabs had scarcely begun to climb the stones when down came a jackal in full flight and was shot by me. After this little sporting interlude we visited the other Pyramids in the neighbourhood, and the small recently opened one of King Pepi I.

Permit me here to quote some notes about Pyramids in general, those of Memphis and Ghizeh, and also about the Sphinx, for which I am indebted to my friend Brugsch.

“The old national god of Memphis, Ptah, in his special capacity of king of the dead and protector of the departed, bore the name of Sokar. In this capacity he was absolutely identical with the god Osiris of the whole country. A sanctuary dedicated to him on the site of the present village of Sakkara bore the old Egyptian designation ‘house of Sokar,’ from which the Arabic name of the village Sakkara is directly derived. The graves of the Memphites, which are grouped round the Pyramids in regular order, and the oldest of which belong to the period of the Memphite kings, were under the protection of this king of the dead. A whole city of the dead arose on the soil of the desert. Long rows of funeral chapels built in stone, the so-called ‘houses of eternity,’ formed by their continuity the streets of the city. Underneath them, in deep shafts, were the actual chambers in which the departed rested in their wooden or stone coffins. The best-preserved mausoleum of the times of the Memphite kings is that of a certain distinguished Egyptian named Thi. He lived in the middle of the fourth century B.C., and prepared a chapel for himself in the vicinity of the Pyramids of those kings under whose sway he had held his post of officer of state.