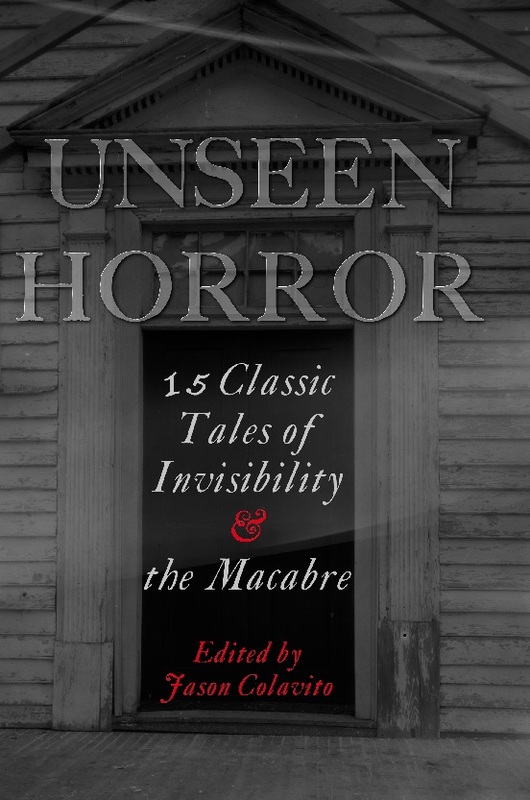

Unseen Horror | EXCERPT |

I was born and reared in a region full of adventure and excitement. My paternal grandfather was one of the pioneers of Kentucky, the romantic history of which is still fresh in many memories. My father inherited from him not only a good farm in a fully settled district, but a large quantity of wild land in a region where the white man, at that period, had scarcely ever ventured save as a hunter.

The love of adventure which had induced my grandfather to become a pioneer, descended to his son; and this, together with a natural desire to improve his property, prompted my father to rent his farm in the “settlements,” and remove to the wilderness very shortly after his marriage.

My mother, herself the daughter of a genuine backwoodsman, cheerfully accompanied him, and delightedly shared his hardships as well as the prosperity which gradually rewarded his toils. In the second year of their sojourn in the forest I was born, and until my eighteenth year I was never actually put of the woods.

Up to that time my education was necessarily scanty, consisting mainly of a tolerable knowledge of the groundwork of the “three R’s,” “Reading, ’Riting, and ’Rithmetic,” imparted to me by my parents in the intervals of their labors, and a thorough professorship in the science of woodcraft, acquired by my own exertions.

In fifteen years, however, my father had so improved his estate, and the country near us had become so much developed, that he found himself one of the most wealthy landholders in the western part of the State, and was suddenly awakened to the consideration of my future. As his only child, and the heir of his vast estate, it seemed proper to both my parents that I should be fitted for the prominent station I was one day to occupy in society, by receiving a suitable education; and within a month subsequent to my seventeenth birthday, I was on my way to Shelbyville to enter the academy at that place.

When I returned home at the age of twenty-one, my friends and neighbors could not comprehend the change in me, and I confess that the majority of them soon heartily despised me. All my old love for hunting and woodcraft was pone, and in its place they found poetry and metaphysics, which made them consider me little better than an idiot. They could not understand how a man with thews and sinews such as mine should shrink from encountering hardship and peril—things which they had sought for, rather than avoided, from their youth—and content himself with writing verses and reading books, which, to their untutored minds, were arrant nonsense. One by one, as I declined their invitations to join them in their during forest sports, those of my own age dropped away from me, and ere long I had acquired among them and their elders the unenviable reputation of a coward.

Alice Campbell was the daughter—the only child—of a rough backwoodsman, whose ruggedness, both of mind and manner, was alone relieved by his strong affection for her. His sole redeeming quality, aside from this affection, was indomitable courage, which he had proved in a hundred perils, and the want of which in any other man he despised beyond all failings.

Alice was, indeed, worthy of his fondness. It seemed to me one of nature’s most singular freaks that she should be the child of that uncouth old hunter—as awkward and ugly as one of the bears he hunted. But the anomaly was in part explained when I came to know his history. In his youth, Ralph Campbell, though never handsome, was well-formed and manly. During the Indian troubles of 1812, he had had the good fortune to rescue a gentleman and his daughter from the savages, just as they were about to be tortured. The heroism he then displayed won the young lady’s heart, and her beauty woke in his a passion that was invincible. In spite of the wealthy father’s opposition they married, and she accompanied her husband to the wilderness, never seeing any of her family again until she lay on her deathbed, ten years afterward.

Her father was then summoned, became reconciled to her, and after her death took his grandchild, Alice, to his home in Virginia. The old man spared no pains or money in her education, and she resided with him until his death, which occurred in her seventeenth year. She then returned to her father, who had given up his roving life, and settled upon a farm some ten miles from my own house.

Though so long separated, the tenderest affection existed between them, and for more than a year before I met her, she had been the light of the old man’s dwelling, her own loveliness and refinement being all the more striking hum the strong contrast which everything surrounding her presented.

My parents had soon perceived my inclinations, and were well content to receive my darling as their daughter—for no one who knew her could help loving Alice. It only remained, therefore, to obtain her father’s consent; and in the evening of the day on which she had made the sweet confession that her heart was mine, I rode over to find him, and formally ask that consent.

I found Ralph Campbell, surrounded by several of his cronies as rough as himself, in what might be called the “forum” of the village—for it was the place where everybody met to discuss the important questions of the day—the store of the principal trader. I was well-known to most of them; and, though I knew that for some time past they had not been friendly toward me—a feeling which I had set down to envy—I had no hesitation in mingling with the group, and saluting them politely. They received me very coldly, and, as soon as an opportunity offered, I requested Mr. Campbell to grant me a private interview.

Without moving from his seat, he rudely surveyed me from top to toe, and then turned most contemptuously away, as if I was not worthy of an answer. My neat and somewhat fashionable attire certainly afforded a striking contrast to the buckskin and homespun suits of those about me, and this might naturally excite scorn in a backwoodsman, if he had been a stranger to me. Bat I felt at once that Ralph Campbell’s contempt had another source, though I could not divine its nature.

To quarrel with him, however, was, of course, the most remote thing from my desire, and curbing my resentment as well as I could, I civilly reiterated my request.

“I’ve no secrets from any of my friends, young man,” said he, rudely. “If you’ve got anything to say to me, spit it out here.”

Astonished at his demeanor, so utterly unexpected, I replied, with much embarrassment, that the subject on which I wished to converse with him was not calculated for public discussion.

“I don’t agree with you,” said be, still more rudely, “for l know what you want of me. You’ve come to ask me for Alice; but let me tell you, once for all, that no one of your breed shall have Rough Ralph’s daughter while he’s on top o’ the earth to say nay!”

Thunderstruck at these words, at first I could do nothing but stare at him stupidly, in silence. Asnickering laugh that ran round the circle restored my self-possession by rousing my anger; but there was too much at stake for me to give way to wrath yet, and, with a powerful effort to control myself, I managed to ask him plainly what his objection to me was.

The answer was much more unexpected thin aught that had gone before, and a hundred times more astounding.

“You’re a sneaking coward!” said he, with an expression of withering scorn; “and if that’s not objection enough for any father in Old Kalmuck, I don’t know what is!”

The blood rushed to my head in a torrent—my brain was in a whirl! Foran instant I thought to strike the old man to my feet; but the sweet face of his daughter rose up before me, and I drew back. Again the sneering laugh ran round the circle, and afforded me another vent for my consuming rage.

Like a wounded lion watching a chance to spring upon his assailants, I faced the ribald crew.

“Ralph Campbell,” I said, slowly, “you are her father, and, therefore, sacred from me. But if any other man dare say such words to me——”

The words bad scarcely passed my lips when a youth—a rough churl whom I had long suspected, but disdained, as a rival—stepped before the crowd, and interrupted me.

“I’m your man, Frank Atherton!” cried he, insolently. “I’m Ben Burton, of Snake Creek, Everybody knows me—and I say you’re a sneaking coward!”

Instantly the fury which I had so violently suppressed flamed up, and I gathered myself together to spring upon him. But at that moment my evil fortune culminated.

In the very act of rushing at my foe, I fell prostrate at his feet—blood gushing from my mouth and nostrils, and the sneering laugh of the bystanders once more ringing in my ears as I sank into complete insensibility.

The crowd supposed—and, afterward, I could scarcely blame them, for fainting was something unknown to their rugged natures—that I had actually been frightened into a fit by the near prospect of a fight.

When I recovered my senses, they had all departed—probably deeming me unworthy even of pity—and I was alone with the trader who owned the store. The first words of his which I understood brought back the recollection of all I had endured, and, wild with shame and wrath, I rushed from the building, mounted my horse, and rode madly away into the forest, intent only on pursuing the slanderer, and washing out the insult in his heart’s blood.

If I had found Burton that night, my soul would doubtless hare been stained with murder, or I should have been slain. But he was not at his home—whither I rode—or expected there for some days; and when I returned to the village, thinking to find him there, I learned that be had gone to another town some thirty miles away.

It was too late to follow him that night, and too late to return to my own home. Wearied in body, and terribly depressed in mind, I, therefore, sought the little tavern of the village; and, having seen my horse provided for, retired to the bedroom to which the landlord conducted me.

Exhausted with the torrent of emotion which for the last four hours had convulsed me, I extinguished the light, and threw myself upon the bed without undressing. To sleep, however, was impossible.

One by one the noises in the house died away as its inmates retired to rest, and, at last, all “was profoundly silent; but the stillness brought me no repose.

The time went slowly by, and had reached that hour just before the dawn which is, proverbially, the darkest, when suddenly a fearful shriek burst on my ears!

Broad awake, and sitting upright on the instant, I stared into the black darkness as if my eyeballs would start from their sockets. That horrid scream still rang in the air, dying away among discordant echoes that repeated and prolonged it as if they would carry it to heaven’s very gates; and just before me—so near that I could almost touch them, and on a level with my own face—I saw four shining points that I instantly knew to be eyes, though no human eyes ever flashed so like to flame!

Again that horrid yell awoke the dismal echoes, and so terrible was the shock that it conveyed to my nerves that I bounded from the bed to the floor without knowing that I did so. Scarcely had I gained my feet when my outstretched hands encountered a smooth surface that seemed covered with hair, and the next instant I was down upon the floor, clasped in the deadly embrace of an invisible monster, whose teeth and talons pierced and tore my flesh in a dozen different places at once, with a sharp, fiery pang, as of red-hot irons!

For a few moments I was less frightened than astonished, but as I struggled with my unseen assailant, I suddenly discovered that it had two heads, and more than four limbs, with but a tingle body!

Idid not cease to struggle, though the effort was entirely mechanical, and was not in any way the result of will.

The sharp, burning talons of the fiend continued to rend my flesh; his hot breath and venom poured upon my face, apparently searing it to the bone; but still my hands grasped his dual throat, and still my quivering muscles strove to tear him off, and cast him from me!

The effort, tremendous as it was, proved vain. And now the grey light of the dawn came stealing in at the casement, making plainly visible the white ceiling above me, and faintly revealing the furniture of the chamber.

Oh, God, most merciful I banish from my mind the memory of that moment, supreme in horror!

My hands still grasped the hairy throats, the myriad claws still rent and tore me, the four gleaming eyes still glared into mine, but, beyond those eyes, no vestige of a form was visible!

The fiend who so palpably clutched my agonised body, and who seemed intent on dragging my soul forth, to bear it to his infernal home, was viewless, though tangible—a solid, moving, breathing form, utterly invisible, save the four blazing eves that seemed to flame with the fires of Gehenna!

With or lust effort of profound despair, I wrenched the unseen monster from its deadly hold, and, staggering to my feet, fell down again, with a shock that shook the house, once more perfectly insensible!

* * * * *

“Where am I? Was not that Ralph Campbell’s voice?”

I was lying on the bed in the same chamber, my body and head swathed in voluminous bandages, and Alice herself was bathing my brow with a cooling lotion. Rough Ralph stood at her side, his rugged face beaming joyously, and his brawny band clasping mine as if he never meant to let go of it.

“It’s me, my boy, and no mistake!” cried he, exultingly; “and here’s Alice, too, who may marry you to-morrow, if she likes! A man who can fight two halt-starved, full-grown wildcats in the dark, without a we’pon—and kill ’em, too— hasn’t got much coward about him, I’m blessed if he has!”

Courteous reader, that was the simple, unvarnished truth. The landlord of the tavern had lately caught a pair of wildcats, a male and a female, and had them confined in a wooden cage, which he had placed in a loft over the room I occupied. They had broken out of their cage, and made their way into my apartment through a trap-door, having first entangled themselves in a fishing-net, which bound them together, and caused their bodies to seem like one to me—probably, also, preventing them from clawing me quite to death in our struggle.

As to their invisibility, everybody who has hunted such beasts knows that their peculiar, dusky color renders it almost impossible to distinguish them amid the trees, even in broad day. The grey light of dawn would exactly match their hue, and this, together with the dimness of my sight, from the straining it had undergone, fully explains why they were indiscernible to me.

In due time my darling Alice became my wife, and Ben Burton, of Snake Creek, was my “best man” on that interesting occasion. He and his comrades were thereafter quite satisfied that the man was no dastard who, in their expressive Western phrase, could “whip his weight in wildcats!”