William D. Matthew

1909

|

NOTE |

William D. Matthew (1871-1930) was a paleontologist who had the misfortune to be wrong on many major issues. He believed that humans evolved in Asia, that Tibet was the fountainhead of evolution, and that climate change rather than continental drift was responsible for the differences between Old World and New World species. Nevertheless, his opening chapter to volume 6 of the Science-History of the Universe (1909), on the relationship between myth and zoology, contains many useful insights into the entwined but oppositional relationship between mythology and science.

|

Fabulous Zoölogy

The beginnings of Zoölogy lie in the region of fable. In the earliest traditions and myths of primitive races the world is peopled with men and animals, some real, some half-real, some entirely fabulous. Natural and supernatural are mingled together and a religious or superstitious significance attaches to both real and unreal beings seen or imagined by primitive man. His ready imagination and uncritical belief made the creations of his fancy seem as real as those of his observation and experience. With the increase of knowledge of the real, the unreal became more and more relegated to the domain of folklore and fable. Some of it has been preserved in the traditions and myths of different races, some crystallized in the fanciful animals of decorative sculptures, paintings and heraldry. Most of it has been forgotten.

It has been well observed that the imagination of man does not really enable him to create anything new, but only to recombine or rearrange what he has seen. He may combine the body of a reptile with the wings of an eagle; he may combine the head and shoulders of a man with the body and legs of a horse or attach to a human form the white wings of a swan. He may in fancy enlarge a mouse to the size of an elephant or conceive of a serpent large enough to encircle the whole world; he may support the universe upon the back of an elephant of appropriate size. But all these are not new creations; they are objects known to his experience, but recombined or altered in proportions. It is only as he comes to realize with wider knowledge that certain combinations of parts, certain relations of size do not occur in nature, that these imaginary beings become improbable or impossible. He is accustomed to supply the missing parts of half-seen animals from his previous observations. He sees the head of a deer projecting from the leafy wall of the forest and all unconsciously pictures the rest of the quadruped from what he has seen before; he sees a distant eagle perched upon a crag and knows well enough that when it starts to fly it will stretch out a pair of broad wings now closely folded against the body and invisible in the distance. If then he sees dimly outlined in the clouds a human form, what more natural than to supply it with the long feathered wings that belong to the birds of the air, or if at night with the wings of the bats that infest his cave dwelling? Nearly all of the fabulous monsters of zoölogy belong to this early period. They have been handed down conventionalized in form and degenerated into fable, but originally they were just as real as the rest of the half-seen, half-imagined world in which primitive man existed. Perhaps the most familiar and universally known of these fabulous animals is the dragon. It appears in all the older myths of the Western nations in serpent form, usually winged, often with fiery or pestilential breath, the deadly enemy and scourge of man. It is equally prominent among the Eastern peoples, and probably received from them its conventional form, the long hind legs, the great eagle claws, the body covered with glittering armor scales, the writhing tail and bat-like wings. Among the Mediterranean nations it appears first as a sea monster and comes up out of the sea; wings were a later addition. In the Northern myths it is at first a "worm"--i.e., a serpent of gigantic size—and the conventional form is borrowed later from the East.

The fabulous Dragon had a real counterpart, singularly close in some respects, in the extinct carnivorous Dinosaurs of the Age of Reptiles. These gigantic reptiles were not winged, indeed, but in the proportions of body, limbs and tail, in the huge head and sharp teeth, the enormous, sharp, eagle-like claws, possibly even in the glittering scaly armor, some of them at all events might have sat for a very tolerable portrait of the dragon of mythology. It is a tempting explanation to suppose that some tradition of these real monsters, handed down from primitive ancestors, was the basis of the dragon legends so widely scattered among all races of men. But this theory must be regretfully abandoned when the perspective of the geologic record is examined. The last of the Dinosaurs became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous Period, some three million years ago at a moderate estimate, before the evolution of the various races of modern quadrupeds had begun, long before monkeys and apes had evolved out of the primitive lemur-like animals from which they are derived and long, long before the evolution of man. The remote ancestors of the human race in the days of the Dinosaurs were tiny shrew-like animals, inferior in intelligence to almost any living quadrupeds, and millions of years were to elapse before they slowly evolved a higher intelligence and finally became capable of articulate speech. So it is utterly impossible that a tradition could have been handed down from the time when Dinosaurs really existed.

Nor is it to be supposed that the dragon myths are based upon discovery of their fossil remains, for in the millions of years that have elapsed since their time the sand and mud in which their remains were buried have been converted into hard sandstone and shale and the bones so thoroly petrified that they appear much like the rock itself. They would not easily be recognised as bones at all, and it would be quite out of the question for primitive man to get any correct notion of the kind of animals they represented if they happened to come across a few fragments unearthed out of the rock. Dinosaur bones might conceivably pass for bones of giants, but the concept of the dragon could not possibly be founded upon them. There remains a third explanation, that in some region of the world Dinosaurs might have survived until more recent times and have been seen by primitive men. But from what is known of the geological history of life, this supposition is so exceedingly improbable as to amount to an utter impossibility. One is obliged to conclude that the dragon is wholly a creation of the imagination of man, its source being probably among the races of Eastern Asia. How and why it came to assume its present conventional form would require a broad knowledge of the early history and mythology of these races to discern.

In the traditions of the Northern races the dragon legends are engrafted upon the myth of the giant serpent, the "Worm," which in the old Norse story encircles the earth, lying at the bottom of the surrounding ocean. This same myth, in another form, is handed down as the Sea Serpent. Sea serpents, however, are easier to credit than dragons, partly because less is known about the inhabitants of the sea than those of the land, partly because among the multitudinous forms of ocean life there are many that correspond more or less with the preconceived idea of what a sea serpent ought to be like. So that while the dragon is confined to legend and no one professes to have really seen one, there be many, down to the passengers on modern ocean liners, who have testified to seeing a sea serpent of approved type. Sometimes it may be one of the large sea snakes, sometimes a ribbon fish or a school of porpoises following one another as they leap out of the water so as to give the impression of the rolling coils of a great serpent. Sometimes a long streamer or tangle of seaweed may look like the giant serpent with its maned neck which all expect to see. Possibly among the unknown inhabitants of the great deep some such animal may really exist. But until it is captured and its remains deposited in some museum of natural history it must be ranked among fabulous monsters.

The Unicorn of classical writers was a real animal; the great one-horned Rhinoceros of India, well known to Eastern writers and not unfamiliar to the patrons of the Greek or Roman circuses. In medieval Europe it suffered a curious transformation. The Northern artist had never seen a rhinoceros nor talked with any one who had. He knew that it was a great four-legged beast with a long horn on its forehead and the traditional foe of the lion. So he grafted the twisted tusk of a narwhal on the forehead of a horse and in this form it was conventionalized in heraldry, its source not recognised when, centuries later, the rhinoceros was reintroduced to the knowledge of Western nations.

It has been well observed that the imagination of man does not really enable him to create anything new, but only to recombine or rearrange what he has seen. He may combine the body of a reptile with the wings of an eagle; he may combine the head and shoulders of a man with the body and legs of a horse or attach to a human form the white wings of a swan. He may in fancy enlarge a mouse to the size of an elephant or conceive of a serpent large enough to encircle the whole world; he may support the universe upon the back of an elephant of appropriate size. But all these are not new creations; they are objects known to his experience, but recombined or altered in proportions. It is only as he comes to realize with wider knowledge that certain combinations of parts, certain relations of size do not occur in nature, that these imaginary beings become improbable or impossible. He is accustomed to supply the missing parts of half-seen animals from his previous observations. He sees the head of a deer projecting from the leafy wall of the forest and all unconsciously pictures the rest of the quadruped from what he has seen before; he sees a distant eagle perched upon a crag and knows well enough that when it starts to fly it will stretch out a pair of broad wings now closely folded against the body and invisible in the distance. If then he sees dimly outlined in the clouds a human form, what more natural than to supply it with the long feathered wings that belong to the birds of the air, or if at night with the wings of the bats that infest his cave dwelling? Nearly all of the fabulous monsters of zoölogy belong to this early period. They have been handed down conventionalized in form and degenerated into fable, but originally they were just as real as the rest of the half-seen, half-imagined world in which primitive man existed. Perhaps the most familiar and universally known of these fabulous animals is the dragon. It appears in all the older myths of the Western nations in serpent form, usually winged, often with fiery or pestilential breath, the deadly enemy and scourge of man. It is equally prominent among the Eastern peoples, and probably received from them its conventional form, the long hind legs, the great eagle claws, the body covered with glittering armor scales, the writhing tail and bat-like wings. Among the Mediterranean nations it appears first as a sea monster and comes up out of the sea; wings were a later addition. In the Northern myths it is at first a "worm"--i.e., a serpent of gigantic size—and the conventional form is borrowed later from the East.

The fabulous Dragon had a real counterpart, singularly close in some respects, in the extinct carnivorous Dinosaurs of the Age of Reptiles. These gigantic reptiles were not winged, indeed, but in the proportions of body, limbs and tail, in the huge head and sharp teeth, the enormous, sharp, eagle-like claws, possibly even in the glittering scaly armor, some of them at all events might have sat for a very tolerable portrait of the dragon of mythology. It is a tempting explanation to suppose that some tradition of these real monsters, handed down from primitive ancestors, was the basis of the dragon legends so widely scattered among all races of men. But this theory must be regretfully abandoned when the perspective of the geologic record is examined. The last of the Dinosaurs became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous Period, some three million years ago at a moderate estimate, before the evolution of the various races of modern quadrupeds had begun, long before monkeys and apes had evolved out of the primitive lemur-like animals from which they are derived and long, long before the evolution of man. The remote ancestors of the human race in the days of the Dinosaurs were tiny shrew-like animals, inferior in intelligence to almost any living quadrupeds, and millions of years were to elapse before they slowly evolved a higher intelligence and finally became capable of articulate speech. So it is utterly impossible that a tradition could have been handed down from the time when Dinosaurs really existed.

Nor is it to be supposed that the dragon myths are based upon discovery of their fossil remains, for in the millions of years that have elapsed since their time the sand and mud in which their remains were buried have been converted into hard sandstone and shale and the bones so thoroly petrified that they appear much like the rock itself. They would not easily be recognised as bones at all, and it would be quite out of the question for primitive man to get any correct notion of the kind of animals they represented if they happened to come across a few fragments unearthed out of the rock. Dinosaur bones might conceivably pass for bones of giants, but the concept of the dragon could not possibly be founded upon them. There remains a third explanation, that in some region of the world Dinosaurs might have survived until more recent times and have been seen by primitive men. But from what is known of the geological history of life, this supposition is so exceedingly improbable as to amount to an utter impossibility. One is obliged to conclude that the dragon is wholly a creation of the imagination of man, its source being probably among the races of Eastern Asia. How and why it came to assume its present conventional form would require a broad knowledge of the early history and mythology of these races to discern.

In the traditions of the Northern races the dragon legends are engrafted upon the myth of the giant serpent, the "Worm," which in the old Norse story encircles the earth, lying at the bottom of the surrounding ocean. This same myth, in another form, is handed down as the Sea Serpent. Sea serpents, however, are easier to credit than dragons, partly because less is known about the inhabitants of the sea than those of the land, partly because among the multitudinous forms of ocean life there are many that correspond more or less with the preconceived idea of what a sea serpent ought to be like. So that while the dragon is confined to legend and no one professes to have really seen one, there be many, down to the passengers on modern ocean liners, who have testified to seeing a sea serpent of approved type. Sometimes it may be one of the large sea snakes, sometimes a ribbon fish or a school of porpoises following one another as they leap out of the water so as to give the impression of the rolling coils of a great serpent. Sometimes a long streamer or tangle of seaweed may look like the giant serpent with its maned neck which all expect to see. Possibly among the unknown inhabitants of the great deep some such animal may really exist. But until it is captured and its remains deposited in some museum of natural history it must be ranked among fabulous monsters.

The Unicorn of classical writers was a real animal; the great one-horned Rhinoceros of India, well known to Eastern writers and not unfamiliar to the patrons of the Greek or Roman circuses. In medieval Europe it suffered a curious transformation. The Northern artist had never seen a rhinoceros nor talked with any one who had. He knew that it was a great four-legged beast with a long horn on its forehead and the traditional foe of the lion. So he grafted the twisted tusk of a narwhal on the forehead of a horse and in this form it was conventionalized in heraldry, its source not recognised when, centuries later, the rhinoceros was reintroduced to the knowledge of Western nations.

|

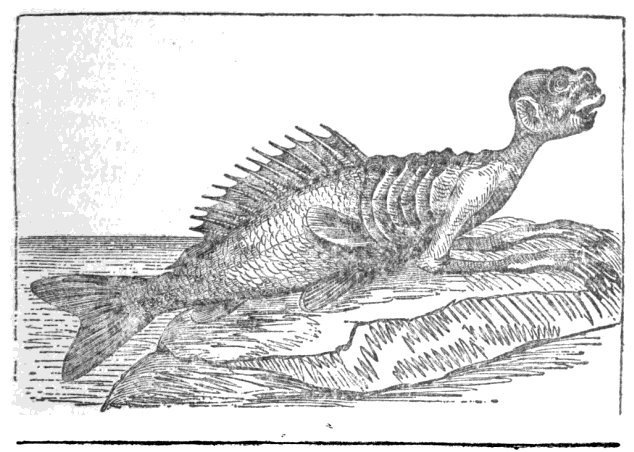

The various composite monsters of the mythology of different races—the Centaurs and Sirens of the Greeks, the Mermaids and Swan-maidens of Western Europe, the winged bulls of Assyria or the eagle-headed gods of Egypt—have all a more or less definite religious significance and are theological rather than zoölogical myths. Some of them have survived in zoölogical lore, supported, like the sea-serpent, by the occasional sight of animals more or less resembling what the observer expected to see and their described appearance colored by the traditional description. Mermaids appear every now and then in the accounts of medieval writers; some of the stories may well have been based on the manatee or dugong, while in more recent years actual specimens of stuffed mermaids, manufactured by the ingenious Japanese from the fore part of a monkey and the tail of a fish, have often been exhibited. |

To another class of zoölogical myths belong the innumerable fanciful stories told of the characters and habits of real animals; of the transmutation of men into animals and vice versa, and of the transformation of one species of animal into another. Real metamorphosis of form, as of the tadpole into the frog or of the larva into the perfect insect, is well known to modern natural history, but however much or little a primitive ancestry may have known about it, there seems to be no good reason to believe that the enchantment-transformations of mythology originated in any real observations of metamorphosis in nature. Dream experiences imperfectly separated from the recollections of waking hours had probably much to do with their conception. Hence it would seem that while Natural History possesses relations which may throw its beginnings to the fabulous monsters of ancient times, the same cannot be said for the Science of Zoölogy, which as a science requires evidence, and having classified that evidence is loth to admit therein such mythical creatures who are undoubted aliens.

|

Source: William D. Matthew, "Zoölogy," in The Science-History of the Universe, ed. Francis Rolt-Wheeler, vol. VI: Zoology and Botany (New York: The Current Literature Publishing Company, 1910), 1-6.

|