Many cities have been imagined to exist somewhere just beyond the known world. Some of the original texts related to these lost cities are reproduced below.

THE WHITE CITY OF HONDURAS

Hernando Cortés, fifth letter to Charles V (Sept. 3, 1526)

…I hear of large and rich provinces and great lords who live in them in much state and magnificence; especially of one, called Hueitapalan, and, in another dialect, Xucutaco, of which I have heard for six years past, and during the whole of my journey have made inquiries about it and ascertained that it lies some eight or ten days’ march from Trujillo, which would be between fifty and sixty leagues. There are such wonderful reports about it that they excite my admiration, for, even if two-thirds of them should be untrue, it would nevertheless exceed Mexico in wealth and equal it in the grandeur of its towns, the multitude of its population, and its political organisation.

Translated by F. A. MacNutt.

Translated by F. A. MacNutt.

Eduard Conzemius, “Los Indios Payas de Honduras,” Journal de la Société des Américanistes 19 (1927)

White City.

In this part of Honduras it is believed that on the bank of the Rio Platano, in its upper course, there are important ruins which were discovered by a hulero (rubber tapper) about 20-25 years ago, when he was lost on the mountain between the rivers Plátano and Paulaya. He left this name and a fantastical description of what he saw there. It was the ruins of a very important city with white buildings of a stone similar to marble, surrounded by a large wall of the same material. Shortly afterward, this Ladino disappeared in La Mosquitia, and nobody knows what became of him. An old Paya (Pech) saurín (shaman) then said that the devil had killed him for daring to contemplate this forbidden place, which this Indian knew from his ancestor.

By dint of the white buildings, this place was known by the name “White City.” After a few years, a mulatto, who went exploring in the small tributaries left of the Rio Platano, claimed to have found the ruins, but after a few days of making this report, he drowned in the river and the Indians attributed his death to the anger of the devil.

Despite the great measures that the Ladinos and foreigners have undertaken in order to obtain a guide, they have never found a Paya to lead them to these ruins. All the Indians say that they do not know of it and that it is all a myth, but the other residents of the coast affirm that they do not want to show these ruins to others for fear that then they would die.

Translated by Jason Colavito.

In this part of Honduras it is believed that on the bank of the Rio Platano, in its upper course, there are important ruins which were discovered by a hulero (rubber tapper) about 20-25 years ago, when he was lost on the mountain between the rivers Plátano and Paulaya. He left this name and a fantastical description of what he saw there. It was the ruins of a very important city with white buildings of a stone similar to marble, surrounded by a large wall of the same material. Shortly afterward, this Ladino disappeared in La Mosquitia, and nobody knows what became of him. An old Paya (Pech) saurín (shaman) then said that the devil had killed him for daring to contemplate this forbidden place, which this Indian knew from his ancestor.

By dint of the white buildings, this place was known by the name “White City.” After a few years, a mulatto, who went exploring in the small tributaries left of the Rio Platano, claimed to have found the ruins, but after a few days of making this report, he drowned in the river and the Indians attributed his death to the anger of the devil.

Despite the great measures that the Ladinos and foreigners have undertaken in order to obtain a guide, they have never found a Paya to lead them to these ruins. All the Indians say that they do not know of it and that it is all a myth, but the other residents of the coast affirm that they do not want to show these ruins to others for fear that then they would die.

Translated by Jason Colavito.

NORUMBEGA

Jehann Allefonsce (João Afonso), Cosmographie (Ms.) (1545)

The River is more than forty leagues wide at its entrance, and retains its width some thirty or forty leagues. It is full of Islands, which stretch some ten or twelve leagues into the sea, and are very dangerous on account of rocks and shoals. The said river is in 42 N. L. Fifteen leagues within this river there is a town called Norombega, with clever inhabitants, who trade in furs of all sorts; the towns folk are dressed in furs, wearing sable. I question whether the said river enters the Hochelaga. For more than forty leagues it is salt water, at least so the town folk say. The people use many words which sound like Latin. They worship the sun. They are tall and handsome in form. The land of Norombega lies high and is well situated.

Translated by Benjamin Franklin DeCosta

Translated by Benjamin Franklin DeCosta

THE CITY OF THE CAESARS

Pedro Cieza de Léon, Wars of Chupas 85 (c. 1553)

There were highly promising reports of the provinces extending to the west [sic!], where the very large and powerful river of La Plata flows, so broad that when it enters the Ocean it appears more like some arm of the sea than a river. In former times, when its mouth was discovered, certain Spaniards who ascended this river recounted great things; but the fame of such stories always exceeds the reality. It was said that there was so vast a quantity of gold and silver that the Indians held it for nought, and that there were emeralds there as well.

I knew Francisco de César, who was a captain in the province of Cartagena, which is situated on the coast of the Ocean, and one Francisco Hogaçon, who was also one of the first conquerors of that province, and I have often heard them talk, and affirm with an oath that they saw much treasure and great flocks of the cattle we call here Peruvian sheep, and that the Indians were well dressed and of good mien. They said many other things that I need not write of. Afterwards Don Pedro de Mendoza went out as Governor to that country, and events took place which I will relate in the account of the last war and the coming of the President Pedro de la Gasca.

As the fame of that rich country spread far and wide many desired to be in it. When the captain Pedro Anzures went to explore the Chunchos, he got reports of that river. It was supposed that it had its source in the lake of Bombon; and that the principal affluents of this river of La Plata were the Apurimac and the Jauja. Felipe Gutierrez and the captain Diego de Rojas, desirous of making some conquest which would be memorable and give satisfaction to his Majesty, asked the Governor Vaca de Castro to entrust them with the leadership of an expedition; and as he was anxious to see the soldiers dispersed, the back country opened up and thoroughly explored, and the name of Christ made known in all parts, he was glad of their proposal and very willingly favoured all who wished to take part in the adventure, by furnishing them with arms and horses and money. So he nominated Felipe Gutiérrez as Captain-general, Diego de Rojas as Chief Judge, and Nicolas de Heredia as Camp-master, with the necessary powers and commissions, in the name of our lord the King. In default of Gutiérrez through illness, or being killed by the Indians, Diego de Rojas was to succeed to the chief command; and if, in his turn, Rojas should fail, Heredia was to take over charge. When the soldiers learnt that Diego de Rojas was going to be a leader in the expedition, many, holding him to be a good captain, prepared to follow him.

Translated by Clements Markham. (Brackets are by Markham.)

I knew Francisco de César, who was a captain in the province of Cartagena, which is situated on the coast of the Ocean, and one Francisco Hogaçon, who was also one of the first conquerors of that province, and I have often heard them talk, and affirm with an oath that they saw much treasure and great flocks of the cattle we call here Peruvian sheep, and that the Indians were well dressed and of good mien. They said many other things that I need not write of. Afterwards Don Pedro de Mendoza went out as Governor to that country, and events took place which I will relate in the account of the last war and the coming of the President Pedro de la Gasca.

As the fame of that rich country spread far and wide many desired to be in it. When the captain Pedro Anzures went to explore the Chunchos, he got reports of that river. It was supposed that it had its source in the lake of Bombon; and that the principal affluents of this river of La Plata were the Apurimac and the Jauja. Felipe Gutierrez and the captain Diego de Rojas, desirous of making some conquest which would be memorable and give satisfaction to his Majesty, asked the Governor Vaca de Castro to entrust them with the leadership of an expedition; and as he was anxious to see the soldiers dispersed, the back country opened up and thoroughly explored, and the name of Christ made known in all parts, he was glad of their proposal and very willingly favoured all who wished to take part in the adventure, by furnishing them with arms and horses and money. So he nominated Felipe Gutiérrez as Captain-general, Diego de Rojas as Chief Judge, and Nicolas de Heredia as Camp-master, with the necessary powers and commissions, in the name of our lord the King. In default of Gutiérrez through illness, or being killed by the Indians, Diego de Rojas was to succeed to the chief command; and if, in his turn, Rojas should fail, Heredia was to take over charge. When the soldiers learnt that Diego de Rojas was going to be a leader in the expedition, many, holding him to be a good captain, prepared to follow him.

Translated by Clements Markham. (Brackets are by Markham.)

Ruy Díaz de Guzmán, La Argentina 1.9 (1612)

In the sixth chapter of this book I told how Sebastian Cabot had dispatched men to discover the southern and western lands that could be found on that side (of the Rio de la Plata), following the opinion born of his understanding and cosmography, for it seemed to him that this was the easiest and shortest way to enter the rich kingdom of Peru and its confines, for which I said he had sent (Francisco) César and his companions. To this end, from the fortress of Sancti Spiritus, where they began to their journey, they went by some Indian villages, and crossing a ridge that comes from the coast of the sea, and running to the west and north, it joins together with the general and high mountains of Peru and Chile, making between the two some very large and spacious valleys full of many Indians of various nations; and they passed through these, encountering many populations of Indians who entertained them and gave them passage. They continued their journey back to the south, where they entered a province of great size and with many people, rich in gold and silver, who had together a large number of cattle and sheep of the land (llamas), whose wool they made into a great amount of tightly woven clothing. These natives obey a lord who rules over them, and for greater safety the Spaniards sought his protection and determined to go where he was. They arrived in his presence, and with reverence and respect they gave their embassy, in the best way possible to them, giving him redress for their coming, and asking friendship on behalf of His Majesty, who was a powerful prince who had his kingdom and dominion on the other side of the sea, not because he needed to acquire new lands and estates, nor for any other interest than to have him as a friend, and to preserve their friendship, as he does with many other princes and kings, and for his zeal to let him know the true God. In this particular the Spaniards, with great modesty, did not fall afoul of that gentleman, who received them kindly and treated them well, really enjoying the conversation and manners of the Spaniards; and there they tarried for many days, until César and his companions asked him permission to return, which the lord gave them, liberally presenting them with many pieces of gold and silver, and loading them down with as much clothing as they could carry, and he gave them Indians to accompany and serve them; and traveling through the land, they came through this course back to the fortress from which they had departed, but which they found deserted and desolate, after the unfortunate incident of Don Nuño de Lara, and the others who with 61 died. Seeing this, César returned with his company back to this province, where after a few days they determined to leave the land and move forward, passing through many regions and districts of Indians of different languages and customs; and climbing a high and rough mountain, they were able to see the hemisphere formed from a part of the sea to the North and the other to the South: although this does not persuade me of the distance from one sea to another; for, taking it for so narrow, there may be in the corner of the Strait of Magellan, there, a passage from a part of the North to the other sea of the South, more than a hundred leagues, but from what I understand they were deceived by some large lakes known to fall from this other part of the North, and looking at them from above made them seem to be a part of the same sea. Walking from this place along the South coast for many leagues, they went to Atacama, land of the Olipes, and leaving the Charcas by the right, they were in reach of Cuzco. They entered the kingdom at the time when Francisco Pizarro had just imprisoned Atahualpa in the Tambo in Cajamarca, as stated in his history. So, with this event, whose name is commonly called the conquest of the Caesars, César had crossed the whole land, as certified to me by the captain Gonzalo Sáenz Garzón, a resident of Tucuman, an old conqueror of Peru, who told me that he knew and communicated with this César in the city of the Kings, and from whom I have taken the relation and discourse referred to in this chapter.

Translated by Jason Colavito.

Translated by Jason Colavito.

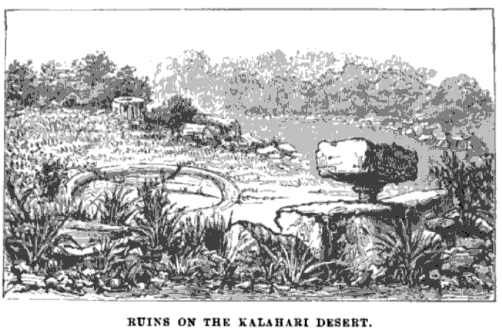

THE LOST CITY OF THE KALAHARI

G. A. Farini, Through the Kalahari Desert, chapter 21 (1886)

Going further south, the trees became more and more scanty. On the second day we sighted a high mountain, which Jan thought was the Ki Ki Mountain on the Nosob River. But we were not far enough south for that, and on reaching the foot of it, it turned out to be one that nobody seemed to have ever seen or heard of. We camped near the foot of it, beside a long line of stone which looked like the Chinese Wall after an earthquake, and which, on examination, proved to be the ruins of quite an extensive structure, in some places buried beneath the sand, but in others fully exposed to view. We traced the remains for nearly a mile, mostly a heap of huge stones, but all flat-sided, and here and there with the cement perfect and plainly visible between the layers. The top row of stones were worn away by the weather and the drifting sands, some of the uppermost ones curiously rubbed on the underside and standing out like a centre-table on one short leg.

The general outline of this wall was in the form of an arc, inside which lay at intervals of about forty feet apart a series of heaps of masonry in the shape of an oval or an obtuse ellipse, about a foot and a half deep, and with a flat bottom, but hollowed out at the sides for about a foot from the edge. Some of these heaps were cut out of solid rock, others were formed of more than one piece of stone, fitted together very accurately. As they were all more or less buried beneath the sand, we made the men help to uncover the largest of them with the shovels—a kind of work they did not much like—and found that where the sand had protected the joints they were quite perfect. This took nearly all one day, greatly to Jan's disgust: he could not understand wasting time uncovering old stones; to him it was labour thrown away. I told him that here must have been either a city or a place of worship, or the burial-ground of a great nation, perhaps thousands of years ago.

The general outline of this wall was in the form of an arc, inside which lay at intervals of about forty feet apart a series of heaps of masonry in the shape of an oval or an obtuse ellipse, about a foot and a half deep, and with a flat bottom, but hollowed out at the sides for about a foot from the edge. Some of these heaps were cut out of solid rock, others were formed of more than one piece of stone, fitted together very accurately. As they were all more or less buried beneath the sand, we made the men help to uncover the largest of them with the shovels—a kind of work they did not much like—and found that where the sand had protected the joints they were quite perfect. This took nearly all one day, greatly to Jan's disgust: he could not understand wasting time uncovering old stones; to him it was labour thrown away. I told him that here must have been either a city or a place of worship, or the burial-ground of a great nation, perhaps thousands of years ago.

“Yah! Sieur, that may be; but it’s no good to us; we cannot carry the stones with us, and could not sell them if we could. Besides, we want to get home to our wives.” Virtuous Bastards! their wives were of more interest to them than antiquities; and now that they had once started they were anxious to get home, especially as, having plenty of meat and skins, they would be received with open arms. When we told Jan that we would remain another day or two to explore the place, he said he knew his people would not dig any more, and doubted if they would even stay.

But when he found out that we did not care whether he and his people went or not, and that, as for the digging, we were independent—we could do that ourselves, much better and quicker—he said if we were foolish enough to dig after a lot of old rocks, he could not prevent us; but, while we were wasting our strength, he would go hunting.

So the next day we had it all to ourselves, and the discoveries we made amply repaid us for our labours. On digging down nearly in the middle of the arc, we came upon a pavement about twenty feet wide, made of large stones. The outer stones were long ones, and lay at right angles to the inner ones. This pavement was intersected by another similar one at right angles, forming a Maltese cross, in the centre of which at one time must have stood an altar, column, or some sort of monument, for the base was quite distinct, composed of loose pieces of fluted masonry. Having searched for hieroglyphics or inscriptions, and finding none, Lulu took several photographs and sketches, from which I must leave others more learned on the subject than I to judge as to when and by whom this place was occupied. For myself, I have ventured to sum up my conclusions on the subject in the following verses:--

A half-buried ruin—a huge wreck of stones

On a lone and desolate spot;

A temple—or a tomb for human bones

Left by man to decay and rot.

Rude sculptured blocks from the red sand project,

And shapeless uncouth stones appear,

Some great man’s ashes designed to protect,

Buried many a thousand year.

A relic, may be, of a glorious past,

A city once grand and sublime,

Destroyed by earthquake, defaced by the blast,

Swept away by the hand of time.

But when he found out that we did not care whether he and his people went or not, and that, as for the digging, we were independent—we could do that ourselves, much better and quicker—he said if we were foolish enough to dig after a lot of old rocks, he could not prevent us; but, while we were wasting our strength, he would go hunting.

So the next day we had it all to ourselves, and the discoveries we made amply repaid us for our labours. On digging down nearly in the middle of the arc, we came upon a pavement about twenty feet wide, made of large stones. The outer stones were long ones, and lay at right angles to the inner ones. This pavement was intersected by another similar one at right angles, forming a Maltese cross, in the centre of which at one time must have stood an altar, column, or some sort of monument, for the base was quite distinct, composed of loose pieces of fluted masonry. Having searched for hieroglyphics or inscriptions, and finding none, Lulu took several photographs and sketches, from which I must leave others more learned on the subject than I to judge as to when and by whom this place was occupied. For myself, I have ventured to sum up my conclusions on the subject in the following verses:--

A half-buried ruin—a huge wreck of stones

On a lone and desolate spot;

A temple—or a tomb for human bones

Left by man to decay and rot.

Rude sculptured blocks from the red sand project,

And shapeless uncouth stones appear,

Some great man’s ashes designed to protect,

Buried many a thousand year.

A relic, may be, of a glorious past,

A city once grand and sublime,

Destroyed by earthquake, defaced by the blast,

Swept away by the hand of time.