Manuel M. Villada and Nicolás León

August 15, 1903

translated by Jason Colavito

2017

|

NOTE |

In 1903, the Mexican government appointed a commission to study reports that the bones of a human giant had been uncovered in northern Mexico, in the state of Coahuilla. The investigation had the expected results: Nicolás León, the director of the Mexican National Museum, determined that the bones belonged to a fossil mammoth or mastodon. However, the story is notable because news of the investigation leaked to the press, and a wildly distorted account ended up published in The New York Herald claiming that León had discovered a lost city buried in the Great Flood and populated with innumerable elephants. From there, the fake version of the story ended up in Theosophical, Mormon, creationist, and fringe literature, without recourse to the original, which I translate here for the first time from the October 1903 Bulletin of the National Museum of Mexico.

|

Bulletin of the National Museum of Mexico

|

REPORT issued by the Subscribing Commission, appointed by the Ministry of Justice and Public Instruction, to study an old natural deposit of alleged human bones, in a place in the State of Coahuila.

|

In the Municipality of Ramos Arispe, District of the Center and State of Coahuila, in a direction to the north of its Capital, is located the ranch of “El Corte,” owned by Mr. Lic. D. Arnulfo R. García. The lands of this estate are encompassed by an extensive valley surrounded by chains of more or less elevated mountains, which are probably related to the last spurs of the Sierra Madre Oriental; the valley has two entrances to the west and northeast; the latter gives access to the railways of the Central, to Tampico and Torreón, and of the International, from Monterrey to Reata.

On the west side of the valley and in the direction of the southeast a deep ravine opens up, through which comes the rainwater from an expanse of 2,000 square kilometers and those of all the slopes that are born from its riverbeds. These waters are already falling in the form of strong torrents or of mighty currents that never fail.

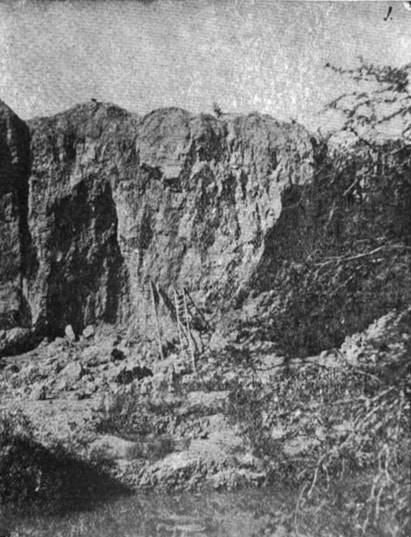

The pronounced slope of the terrain and the abundance of the waters that flow through it have been a sufficient reason for this outlet to have acquired over time a depth of 22 meters and a width somewhat greater than this figure, and it has very little difference, give or take, along its course. But it is to be presumed that its primitive origin was due to the preexistence of some fissure, an accident very common in all lacustrine formations.

In the natural fissure whose two sectional surfaces form the walls of the ravine, and which rise vertically like the walls of a building, (1) a series of overlapping layers of lacustrine sediments appear in rigorously consistent stratification; of variable power and in number up to seven in some places, and in others apparently much more limited; because of its position, in short, noticeably horizontal, there is no disturbance in the layers of its courses. This thick deposit rests, in particular sections, on another haulage layer formed of boulders of medium volume; under these formations there probably extend layers of tuffs and pumice conglomerates, of which there are scarcely any indications.

The material of both formations is entirely lacustrine and alluvial. The first and most important is composed of clay loams and marly clays, exceptionally of sands and carbonaceous particles; usually, very small deposits of liming or travertine are also intercalated. The general color of the sediment is uniformly clear, tending toward dirty white or grayish, with yellowish patches in certain spaces, and of a more or less compact texture in some layers, and in others crumbling.

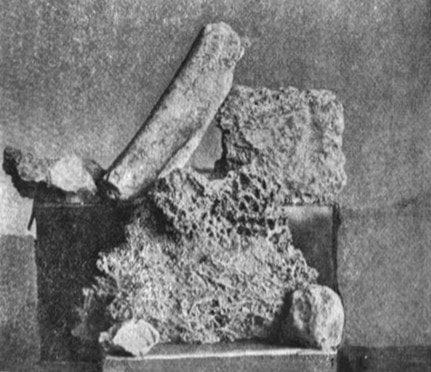

The collapse of a portion of the wall of the ravine that faces north-west revealed parts of a gigantic skeleton supposed to be human, but the only object that led the Commission to explore this land opened by an act of nature was precisely the resolution of this problem. Indeed, in the indicated place could be seen two large bones solidly embedded in the sediment of that wall; each one placed parallel in a vertical position, maintaining a distance of 40 centimeters between one another; they had been mistaken for two humerus bones that presented only their back faces; they were located about 8 meters above the water and 14 meters below the bank or edge of the ravine. It was sufficient for the Commission to make a brief examination to ascertain that they were two perfectly fossilized tusks or defenses of elephants of regular size, according to what was visible, with the base of implantation directed upwards, the free extremity downwards and the anterior face and part of the body protruding from the sediment; the one on the left, or the right of the animal, supposing they remain in their true position, had the tip destroyed, and in what remained of it was the characteristic formation of the dentine in concentric layers; the visible portion of these two tusks was about 60 centimeters. For fear of a collapse, which could be dangerous, their extraction was not arranged, leaving them untouched in the same place; but some photographs were taken by the second undersigned author, and these accompany this report. Around the tusks there were no indications of the existence of other parts of the skeleton; however, immediately below and outside of one of them there was a small excavation from which a fragment of a long bone had been extracted, and at the foot of the cliff there was another quite large one, from which other smaller bones of the same type had been disinterred: We noticed that some of these had all the appearance of the petrified brain mass, to which was attached the small hammer bone, or one of those that form the network that runs through the eardrum, and which was quite notable for its large size. The subsequent examination of this piece did not confirm such an assumption. Notwithstanding that the aforementioned remains seemed to be a simple haulage deposit, it is possible that deep within the skeleton of the same animal could be found more or less complete; but its extraction would have been difficult because of the hardness of that sediment.

Having cleared up the question of the problem that had to be solved, the work of the Commission was finished. But with the hope that the results of the exploration would be somewhat more fruitful, the first undersigned author collected other data on the locality, although of a different nature, and these are reported below as an accessory part of this report.

[There follows a lengthy report on regional geology.]

On the west side of the valley and in the direction of the southeast a deep ravine opens up, through which comes the rainwater from an expanse of 2,000 square kilometers and those of all the slopes that are born from its riverbeds. These waters are already falling in the form of strong torrents or of mighty currents that never fail.

The pronounced slope of the terrain and the abundance of the waters that flow through it have been a sufficient reason for this outlet to have acquired over time a depth of 22 meters and a width somewhat greater than this figure, and it has very little difference, give or take, along its course. But it is to be presumed that its primitive origin was due to the preexistence of some fissure, an accident very common in all lacustrine formations.

In the natural fissure whose two sectional surfaces form the walls of the ravine, and which rise vertically like the walls of a building, (1) a series of overlapping layers of lacustrine sediments appear in rigorously consistent stratification; of variable power and in number up to seven in some places, and in others apparently much more limited; because of its position, in short, noticeably horizontal, there is no disturbance in the layers of its courses. This thick deposit rests, in particular sections, on another haulage layer formed of boulders of medium volume; under these formations there probably extend layers of tuffs and pumice conglomerates, of which there are scarcely any indications.

The material of both formations is entirely lacustrine and alluvial. The first and most important is composed of clay loams and marly clays, exceptionally of sands and carbonaceous particles; usually, very small deposits of liming or travertine are also intercalated. The general color of the sediment is uniformly clear, tending toward dirty white or grayish, with yellowish patches in certain spaces, and of a more or less compact texture in some layers, and in others crumbling.

The collapse of a portion of the wall of the ravine that faces north-west revealed parts of a gigantic skeleton supposed to be human, but the only object that led the Commission to explore this land opened by an act of nature was precisely the resolution of this problem. Indeed, in the indicated place could be seen two large bones solidly embedded in the sediment of that wall; each one placed parallel in a vertical position, maintaining a distance of 40 centimeters between one another; they had been mistaken for two humerus bones that presented only their back faces; they were located about 8 meters above the water and 14 meters below the bank or edge of the ravine. It was sufficient for the Commission to make a brief examination to ascertain that they were two perfectly fossilized tusks or defenses of elephants of regular size, according to what was visible, with the base of implantation directed upwards, the free extremity downwards and the anterior face and part of the body protruding from the sediment; the one on the left, or the right of the animal, supposing they remain in their true position, had the tip destroyed, and in what remained of it was the characteristic formation of the dentine in concentric layers; the visible portion of these two tusks was about 60 centimeters. For fear of a collapse, which could be dangerous, their extraction was not arranged, leaving them untouched in the same place; but some photographs were taken by the second undersigned author, and these accompany this report. Around the tusks there were no indications of the existence of other parts of the skeleton; however, immediately below and outside of one of them there was a small excavation from which a fragment of a long bone had been extracted, and at the foot of the cliff there was another quite large one, from which other smaller bones of the same type had been disinterred: We noticed that some of these had all the appearance of the petrified brain mass, to which was attached the small hammer bone, or one of those that form the network that runs through the eardrum, and which was quite notable for its large size. The subsequent examination of this piece did not confirm such an assumption. Notwithstanding that the aforementioned remains seemed to be a simple haulage deposit, it is possible that deep within the skeleton of the same animal could be found more or less complete; but its extraction would have been difficult because of the hardness of that sediment.

Having cleared up the question of the problem that had to be solved, the work of the Commission was finished. But with the hope that the results of the exploration would be somewhat more fruitful, the first undersigned author collected other data on the locality, although of a different nature, and these are reported below as an accessory part of this report.

[There follows a lengthy report on regional geology.]

National Museum, August 15, 1903

Manuel M. Villada and N. León

Manuel M. Villada and N. León

Source: Boletín del Museo National de Mexico (2nd series) 1, no. 4 (October 1903): 169-172.