Various Authors

1911

|

NOTE |

German scholar Leo Frobenius could not believe that Black Africans were capable of civilization, so he proposed that African culture was the faded remnants of a high white civilization originating in Atlantis, which they crudely imitated. He supported his hypothesis with a multi-volume book, translated into English in 1913. Below are the first reports of his African Atlantis theory, as recorded in the New York Times, the Burlington Magazine, and the American Antiquary in 1911.

|

THE NEW YORK TIMES, January 30, 1911

GERMAN DISCOVERS ATLANTIS IN AFRICA

Leo Frobenius Says Find of Bronze Poseidon Fixes Lost Continent's Place;

NEAR GULF OF GUINEA

Leader of German Expedition into Togo Hinterland Declares Famous Region of Greek Legend Is There.

|

Special Cable to THE NEW YORK TIMES.

BERLIN, Jan. 29. -- Leo Frobenius, author, leader of the German Inner-African exploring expedition, sends word from the hinterland of Togo, according to information reaching THE NEW YORK TIMES correspondent, that he has discovered indisputable proofs of the existence of Plato's legendary continent of Atlantis.

He places Atlantis, which he declares was not an island, in the northwestern section of Africa, in territory lying close to the equator.

The explorer bases his assertions principally on the discovery of an ancient bronze, the head of a man. It is a work of high artistic merit, he says, and dates back to the period ages before the day of Solon, when tradition peopled the legendary continent with a mighty nation which only the Athenians could conquer.

The bronze bears the insignia of Poseidon, the Greek equivalent of Neptune, and this fact is thought by the discoverer to bear out the tradition of an invasion of Atlantis by Athenians. Besides this Poseidon was by legend connected with the founding of the state.

The head of the bronze is hollow, and this construction helps establish the period of the work. It is entirely devoid of Negro characteristics and there is no doubt that it cannot have been of local casting. The features are faultless mold, finely traced, and of slightly Mongolian type.

Frobenius asserts that there is other evidences sufficient, to justify his claim that this age has discovered the lost continent of Atlantis, which the Athenian Solon is said by later writers to have believed existed 9,000 years before his time.

Leo Frobenius has been known as an ethnologist, and the expedition which he led into Africa has had for one of its main objects the study of race types and origins. He is a son-of Hermann Theodor Wilhelm Frobenius, a retired Lieutenant Colonel of the German Army, who is also an author. He has collaborated with his father on several occasions. The lost continent of Atlantis, some times believed to contain the Elysian Fields, and always called an island, has been the subject of some dispute. Some students of Greek have believed it to be an authentic tradition handed down through the pens of Greek writers, while others think it a creation of fancy on the part of writers themselves.

Plato is the first writer to mention it and tell its history. He gives its story as told to Solon, the Athenian lawyer, by an Egyptian priest, who had found it in records that went back further than anything the Athenians had. He mentions it in the “Timoeus,” and in the “Critias” indulges in a description of it, wherein it is certain that he at least added to the story from his own imagination.

Nothing has been brought forward in the way of historical substantiation of its existence. As much as has been definitely told of the legend is given in the “Timoeus.”

“The most famous of all Athenian exploits,” Solon is represented as having been told, “was the overthrow of the island Atlantis. This was a continent lying over the Pillars of Hercules, in greater extent than Libya and Asia Minor put together, and was the passage to other islands and to another continent, of which the Mediterranean Sea was only the harbor; and within the pillars the Empire of Atlantis reached to Egypt and Tyrrhenia. This mighty power was arrayed against Egypt and the Hellas and all the countries bordering the Mediterranean. Then did your city bravely, and won renown over the whole earth. For at the peril of her existence, and when the other Hellenes had deserted her, she repelled the invader, and of her own accord gave liberty to all the nations within the Pillars. A little while afterward there was a great earthquake, and your warrior race all sank into the earth, and the great island of Atlantis also disappeared into the sea. This is the explanation of the shallows which are found in that part of the Atlantic Ocean.”

In spite of the apparent limitations as to the possible spots to seek for the lost continent, as they are indicated by the descriptions of Greek literature, there has never been any one location assigned that would suit all the Greek scholars. There have been many attempts to fix the location of the mythical land, the Canary Islands, the Scandinavian Peninsula, the Azores, and even the continent of America having been said to be the land meant by the ancient writers. Archaeologists and Greek scholars in this city were unwilling yesterday to discuss Frobenius’s story. They said that it was impossible to judge or express an opinion on the small data that had been received here, and pointed out that the matter was so obscured by myth and legend that it would be almost impossible to prove anything about it.

“If Leo Frobenius says he has discovered Atlantis,” said Prof. James Rignall Wheeler, Professor of Greek Archaeology and Art at Columbia University, “I suppose that he believes that he has. But it would seem difficult to prove anything one way or other about his find. The finding of Atlantis has become a common occupation, and they look everywhere for it, the Azores Islands being the latest favorite. You cannot, however, give a scientific opinion on the meager data contained in a press dispatch.”

Togo or Togoland, where the expedition led by Frobenius was operating, lies between Dahomey and Ashanti on the gold coast of the Gulf of Guinea. It is a German possession with an area of about 33,000 square miles. The surface consists mainly of a hilly region, but the coast is low, sandy and unhealthful. Agriculture is largely followed by the natives, the chief products being maize, yams, ginger, tapioca, and bananas. The population is estimated at 2,500,000.

He places Atlantis, which he declares was not an island, in the northwestern section of Africa, in territory lying close to the equator.

The explorer bases his assertions principally on the discovery of an ancient bronze, the head of a man. It is a work of high artistic merit, he says, and dates back to the period ages before the day of Solon, when tradition peopled the legendary continent with a mighty nation which only the Athenians could conquer.

The bronze bears the insignia of Poseidon, the Greek equivalent of Neptune, and this fact is thought by the discoverer to bear out the tradition of an invasion of Atlantis by Athenians. Besides this Poseidon was by legend connected with the founding of the state.

The head of the bronze is hollow, and this construction helps establish the period of the work. It is entirely devoid of Negro characteristics and there is no doubt that it cannot have been of local casting. The features are faultless mold, finely traced, and of slightly Mongolian type.

Frobenius asserts that there is other evidences sufficient, to justify his claim that this age has discovered the lost continent of Atlantis, which the Athenian Solon is said by later writers to have believed existed 9,000 years before his time.

Leo Frobenius has been known as an ethnologist, and the expedition which he led into Africa has had for one of its main objects the study of race types and origins. He is a son-of Hermann Theodor Wilhelm Frobenius, a retired Lieutenant Colonel of the German Army, who is also an author. He has collaborated with his father on several occasions. The lost continent of Atlantis, some times believed to contain the Elysian Fields, and always called an island, has been the subject of some dispute. Some students of Greek have believed it to be an authentic tradition handed down through the pens of Greek writers, while others think it a creation of fancy on the part of writers themselves.

Plato is the first writer to mention it and tell its history. He gives its story as told to Solon, the Athenian lawyer, by an Egyptian priest, who had found it in records that went back further than anything the Athenians had. He mentions it in the “Timoeus,” and in the “Critias” indulges in a description of it, wherein it is certain that he at least added to the story from his own imagination.

Nothing has been brought forward in the way of historical substantiation of its existence. As much as has been definitely told of the legend is given in the “Timoeus.”

“The most famous of all Athenian exploits,” Solon is represented as having been told, “was the overthrow of the island Atlantis. This was a continent lying over the Pillars of Hercules, in greater extent than Libya and Asia Minor put together, and was the passage to other islands and to another continent, of which the Mediterranean Sea was only the harbor; and within the pillars the Empire of Atlantis reached to Egypt and Tyrrhenia. This mighty power was arrayed against Egypt and the Hellas and all the countries bordering the Mediterranean. Then did your city bravely, and won renown over the whole earth. For at the peril of her existence, and when the other Hellenes had deserted her, she repelled the invader, and of her own accord gave liberty to all the nations within the Pillars. A little while afterward there was a great earthquake, and your warrior race all sank into the earth, and the great island of Atlantis also disappeared into the sea. This is the explanation of the shallows which are found in that part of the Atlantic Ocean.”

In spite of the apparent limitations as to the possible spots to seek for the lost continent, as they are indicated by the descriptions of Greek literature, there has never been any one location assigned that would suit all the Greek scholars. There have been many attempts to fix the location of the mythical land, the Canary Islands, the Scandinavian Peninsula, the Azores, and even the continent of America having been said to be the land meant by the ancient writers. Archaeologists and Greek scholars in this city were unwilling yesterday to discuss Frobenius’s story. They said that it was impossible to judge or express an opinion on the small data that had been received here, and pointed out that the matter was so obscured by myth and legend that it would be almost impossible to prove anything about it.

“If Leo Frobenius says he has discovered Atlantis,” said Prof. James Rignall Wheeler, Professor of Greek Archaeology and Art at Columbia University, “I suppose that he believes that he has. But it would seem difficult to prove anything one way or other about his find. The finding of Atlantis has become a common occupation, and they look everywhere for it, the Azores Islands being the latest favorite. You cannot, however, give a scientific opinion on the meager data contained in a press dispatch.”

Togo or Togoland, where the expedition led by Frobenius was operating, lies between Dahomey and Ashanti on the gold coast of the Gulf of Guinea. It is a German possession with an area of about 33,000 square miles. The surface consists mainly of a hilly region, but the coast is low, sandy and unhealthful. Agriculture is largely followed by the natives, the chief products being maize, yams, ginger, tapioca, and bananas. The population is estimated at 2,500,000.

THE AMERICAN ANTIQUARY January-March 1911

ARCHAEOLOGICAL NOTES

Leo Frobenius, leader of the German Inner-African exploring expedition, sends word from the hinterland of Togo, that he has discovered indisputable proofs of the existence of Plato’s legendary continent of Atlantis. He places Atlantis, which he declares was not an island, but in the northwestern section of Africa, in territory lying close to the equator. The explorer bases his assertions principally on the discovery of an ancient bronze, the head of a man. It is a work of high artistic merit, he says, and dates back to the period ages before the day of Solon, when tradition peoples the legendary continent with a mighty nation which only the Athenians could conquer. The bronze bears the insignia of Poseidon, the Greek equivalent of Neptune, and this fact is thought by the discoverer to bear out the tradition of an invasion of Atlantis by the Athenians. Besides this Poseidon was by legend connected with the founding of the state. The head of the bronze is hollow, and this construction helped to establish the period of the work. It is entirely devoid of negro characteristics, and there is no doubt that it cannot have been of local casting. The features are of faultless mold, finely traced, and of slightly Mongolian type. Frobenius asserts that there are other evidence sufficient to justify his claim that this age has discovered the lost continent of Atlantis, which the Athenian Solon is said by later writers to have believed existed nine thousand years before his time. Leo Frobenius has been known as an ethnologist, and the expedition which he led into Africa has for one of its main objects the study of race types and origins. Togo or Togoland, where the expedition led by Frobenius was operating, lies between Dahomey and Ashantee on the gold coast of the Gulf of Guiena. It is a German possession with an area of about 33,000 square miles. The population is estimated at two million five hundred thousand. It is impossible to give a scientific opinion on the meagre data thus far received, and it is difficult to prove anything one way or the other until we have more particulars. As Prof. Wheeler, Professor of Greek Archaeology at Columbia University says, “I suppose if Frobenius says he has discovered Atlantis, I suppose that he believes he has.”

THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE, March 1911

PLATO’S ‘ATLANTIS’ RE-DISCOVERED IN AFRICA

By C. H. READ, Ph.D.

The announcement that the lost Atlantis, so circumstantially described by Plato in the ‘Timaeus,’ had been recently discovered by one Dr. Frobenius, a German traveller, would not in itself command much attention. Theworld is now so well trodden that travellers’ tales must possess some literary merit to enable them to pass muster among the highly spiced meats that form the daily fare of the modern reader. Nor, indeed, would such a discovery fitly be recorded in the pages of an artistic periodical. But in the blare of trumpets with which the traveller has described his marvellous find, he lays particular stress on a number of works of art to confirm his theory, and his description excites the imagination to such flights that the creations of Praxiteles or Scopas fall into a secondary plane. By a fortunate chance it is possible for me to enable the readers of THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE to judge for themselves on what kind of foundation these high artistic claims rest.

The story put forward by Dr. Frobenius is that he, a scientific explorer, came to Ifé, which may be called the sacred capital of the Yoruba country, in the English colony of Southern Nigeria; that he there ‘found’ the works of art, and that, having become legally possessed of them, the British Commissioner intervened, and improperly deprived him of the greater part of his treasures. The District Commissioner is Mr. Charles Partridge, F.S.A., author of ‘The Cross River Natives,’ an accomplished and competent official, thoroughly acquainted with the natives and with their traditions and religion. From his account, the objects secured by Frobenius were sacred; they were deposited in the sacred groves of Ifé, and the native chiefs and priests had certainly no desire and hardly even the power to part with them. The methods adopted by the ‘scientific expedition’ to become possessed of the articles need not be described here; they will probably appear in due course, but they hardly included that straightforward frankness that is the white man’s best weapon in dealing with the black race.

The story put forward by Dr. Frobenius is that he, a scientific explorer, came to Ifé, which may be called the sacred capital of the Yoruba country, in the English colony of Southern Nigeria; that he there ‘found’ the works of art, and that, having become legally possessed of them, the British Commissioner intervened, and improperly deprived him of the greater part of his treasures. The District Commissioner is Mr. Charles Partridge, F.S.A., author of ‘The Cross River Natives,’ an accomplished and competent official, thoroughly acquainted with the natives and with their traditions and religion. From his account, the objects secured by Frobenius were sacred; they were deposited in the sacred groves of Ifé, and the native chiefs and priests had certainly no desire and hardly even the power to part with them. The methods adopted by the ‘scientific expedition’ to become possessed of the articles need not be described here; they will probably appear in due course, but they hardly included that straightforward frankness that is the white man’s best weapon in dealing with the black race.

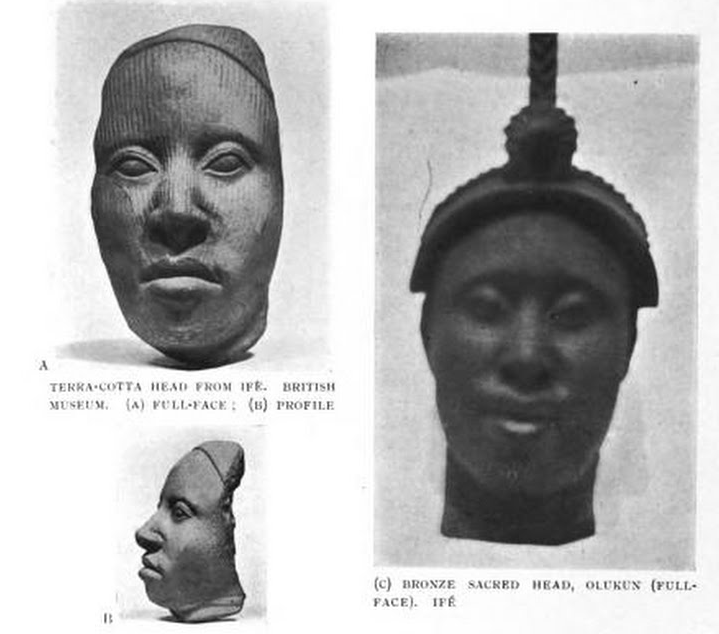

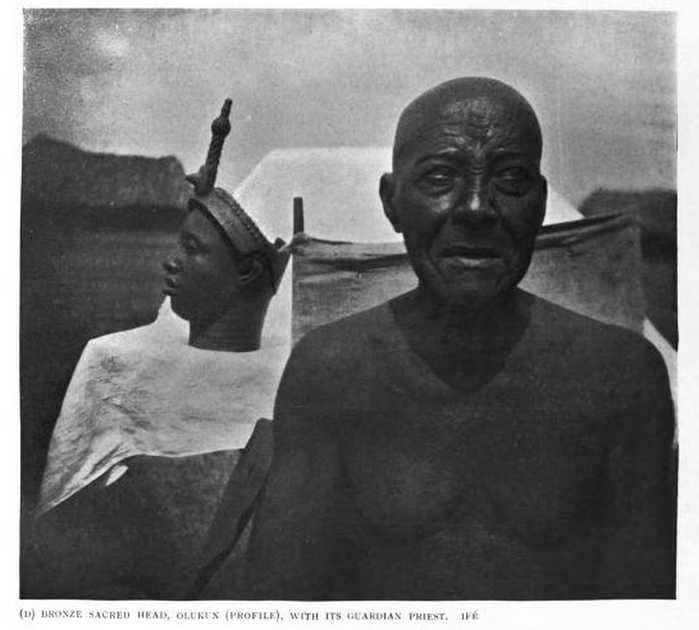

The principal treasure that was disgorged by Frobenius was the bronze head shown in the PLATE [C and D] and to one unaccustomed to the high possibilities of negro art, it doubtless would appear that it belonged to another civilization. Its size can be fairly estimated by comparing it with the figure of the old priest who was its guardian D]. This head was kept in a grove outside the town walls of Ifé and was an object greatly reverenced by the people, to whom it is known by the name of Olokun. As a piece of modelling it reveals an artistic sense and a technical capacity that certainly is unexpected in the heart of West Africa, and a more competent critic than Dr. Frobenius might be forgiven if he were for the moment led astray into wild speculations. It is hardly necessary, however, for us to look beyond its own country for the production of this head, though from what side, or at what date, the inspiration came which made it possible in Yorubaland, is another and a wider question. It will, however, be readily noted that the profile gives a much better impression than the full face view. The head dress is peculiar, and it is also remarkable that the upper part of the head above it is empty, as if for the insertion of a cap of some other material. By a curious coincidence there is in the British Museum a cast of a portion of a face, the original being in terra cotta, that is identical with the bronze just described. This cast is also shown in the PLATE [A and B] ; it is much smaller than the bronze being only 5½ inches in length, but there can be no doubt that it represents the same individual. This terra cotta also comes from Ifé, though details are wanting. Here, however, so far as one may judge from what remains, the artist made a greater success of the front view, and there is a peculiar tenderness in the lines of the mouth, which entirely lacks both the crude convention of the ordinary negro sculptor, and has also little more than a suggestion of the negro lips. No single view, however, can do justice to the subtlety of treatment in the planes of the face, which can only be the work of a most competent artist, and, one would be tempted to think, with a long tradition. One peculiarity of the treatment is not easy to explain—viz., the fact that the whole face is delicately ribbed with diagonal lines, both on the bronze head and on the terra cotta. Tribal marks formed by facial cicatrices are common in West Africa, but they hardly assume this form.

Nigeria is full of monuments of vanished cults, and remains are constantly being unearthed of which the natives profess entire ignorance. lfé is a town of great importance in its modern polity; the Oni of that city having the right of crowning all the rulers of the various Yoruba kingdoms, among them the King of Benin, as a kind of Pope. Here, therefore, if anywhere might be found the art treasures of old times. Mr. Partridge is to be commended and England congratulated on his prompt action in preventing the sacred places of natives under our rule from being pillaged.

Nigeria is full of monuments of vanished cults, and remains are constantly being unearthed of which the natives profess entire ignorance. lfé is a town of great importance in its modern polity; the Oni of that city having the right of crowning all the rulers of the various Yoruba kingdoms, among them the King of Benin, as a kind of Pope. Here, therefore, if anywhere might be found the art treasures of old times. Mr. Partridge is to be commended and England congratulated on his prompt action in preventing the sacred places of natives under our rule from being pillaged.

THE AMERICAN ANTIQUARY, April-June 1911

ARCHAEOLOGICAL NOTES

In a recent number of the Antiquarian we called attention to the declaration recently made by Dr. Frobenius, a German traveler, that he had discovered the site of the lost Atlantis, referred to by Plato in his “Timaeus.” In life, the sacred capital of the Yoruba country in the British colony of Southern Nigeria, Dr. Frobenius found a bronze head and some other works of art which he declared to be evidence of the lost civilization. There has, by the way, been a dispute over the ownership of these objects, the doctor saying that he became legally possessed of them, while the British Commissioner of the district has intervened, asserting that the objects are sacred and not to be touched. Dr. Frobenius’s theory is discredited in an article by the President of the Society of Antiquaries, C. H. Read, in the March issue of the Burlington Magazine. Mr. Read speaks of the high possibilities of negro art, and points out that Nigeria is full of monuments of vanished cults, remains being constantly unearthed of which the natives profess entire ignorance.

Note: I have corrected a printer’s error that transposed parts of two sentences.

Note: I have corrected a printer’s error that transposed parts of two sentences.

Sources: "German Discovers Atlantis in Africa," New York Times, January 30, 1911; Charles H. S. Davis, "Archaeological Notes," The American Antiquary (January-March 1911), 47-48; (April-June 1911), 53-54; C. H. Read, "Plato's 'Atlantis' Re-Discovered in Africa," Burlington Magazine, March 1911, 330-335.