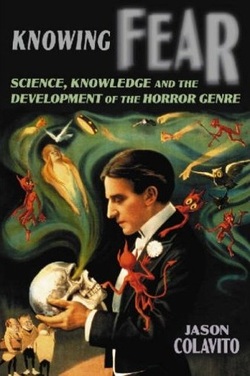

Knowing Fear | EXCERPT |

Introduction:

From Prometheus to Faust

The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.

-- H. P. Lovecraft,

Supernatural Horror in Literature (1927) [n.1]

“How can you read that?”

I can remember nearly every time someone has asked me that when I’ve been caught reading a collection of horror stories, a vampire novel, or any book with a vaguely sinister cover. Substitute “watch” for read and the same question can be heard whenever a new slasher movie, ghost movie, or monster movie opens; for even though horror movies are immensely profitable, they are still not quite respectable. Fear, it seems, is not among the refined emotions critics look for in high art.

But horror is always with us. It lurks in the dark recesses of the soul and the shadows that cut across even the brightest of lights. It is the gnawing fear that the placid surface of our world can and will be shattered by forces beyond our control. For this reason humanity tries, with varying degrees of success, to illuminate the dark places in the world and in our minds, hoping that the light of knowledge can break the power of the unknown evils lying in wait and restore our lives to the imagined happiness of some forgotten past or fantasy future. We study the sciences, psychology, and other fields to make sense of the world and our place in it. And we tell ourselves stories about the horrors that our knowledge helps convince us we have banished. But those things that fade before the light do not stay dead, and knowledge itself is often a source of its own, more exacting terrors. This is the nature of the horror story.

When we think of horror, we often think of monsters: vampires, ghosts, werewolves, witches, and the things that go bump in the night. This is part of horror to be sure, but horror goes beyond simple myths about things that should not be. It is an active essence that captures our fears and crystallizes them into a shape we can understand and set down on paper, on film, or in memory—virtual as well as mental. The monsters of horror can take many shapes, and they can symbolize many things, but one constant remains across time, from the earliest horror stories to the most recent: Knowledge, whether forbidden or achieved, is a primal source of horror.

This goes against most of our instincts, especially for those living in what we call “Western Civilization,” where knowledge is not just the lifeblood of the economy but the way we understand out world: science. For twenty-first century individuals, it is sometimes difficult to imagine a way in which knowledge could be bad, or in fact the source of horror. Instead, when we think about horror at all, we think about it in the terms of Freudian psychoanalysis, positing a range of explanations for the “true” meaning of horror stories, especially psycho-sexual explanations. This is the most popular school of thought about horror, producing works with titles like Walter Evans’s “Monster Movies: A Sexual Theory” (Monsters reflect “two central features of adolescent sexuality, masturbation and menstruation.”), Richard Sanderson’s “Gutting the Maw of Death: Suicide and Procreation in ‘Frankenstein’” (“Victor reveals his fear of female sexual autonomy and his own ambivalent femininity.”), or Joan Copjec’s “Vampires, Breast Feeding, and Anxiety” (“I will argue that the political advocacy of breast-feeding cannot be properly understood unless one sees it for what it is: the precise equivalent of vampire fiction.”), just for example [n.2]. There are many, many more that follow such Freudian views of horror.

Thus do scholars come to interpret Dracula’s fangs as “oral displacement of genital sex, steeped and transformed in nineteenth-century Romanticism” [n.3] Or, more extreme, some begin to see sexual interpretations that aren’t really there, like this one by the horror critic David J. Skal, who felt a little funny when he saw an advertisement for Aurora’s 1960s build-your-own monster models of Dracula, Frankenstein’s Monster, and the Wolf-Man:

Most of the pubescent boys for whom the monster models were intended were no doubt conducting private, one-fisted physical experiments, and, while the official Scout’s handbook frowned upon masturbation, the Boy’s Life ad presented a subliminal tease: Dracula, in his typical mesmeric stance, strokes and pulls at the air; the Frankenstein monster is caught in a startled, “hands-off” pose, and the Wolf Man’s hair-spouting palms hardly require comment. [n.4]

Or maybe they just strike their iconic poses from the famed 1930s and 1940s movies whose scenes the models capture. Somehow, Boris Karloff’s stiff-armed Frankenstein walk never struck me as interrupted masturbation. But while it is beyond dispute that many horror stories deal at some level with sexuality, which after all is one of the basic drives of human life, what Skal and many of the other critics miss is that illicit sexuality is but a subset of a larger horror, one that views knowledge—sexual knowledge included—as the deepest and most profound source of horror a human can know. This horror extends to both forbidden knowledge, which causes horror, and protective knowledge whose loss or corruption creates chaos and pain.

The Mythic Origins of Knowledge-Horror

The tradition of horror stories has deep roots, which stretch back to the earliest human stories and fables. These roots reach directly to the mind itself, for what is horror if not the experience of terror, dread, fear, and unease? These are biological responses to works of art—the horror stories—and they arise from our deepest, most primal reactions. In fact, of all the literary and film genres, perhaps only horror and romance trigger instinctive and physical responses. There is nothing natural or biological about the western, the family comedy, or police procedural. But almost every animal experiences fear since it is a useful instinct for avoiding predators and keeping out of danger, and humans have the imagination to visualize fears yet to come or fears that they may never encounter but dread anyway. That is horror, and it is intrinsic to human nature.

Anatomically modern humans arose sometime around 100,000 to 200,000 years ago, evolving from earlier species like Homo erectus; but only during the upper Paleolithic period (35,000-10,000 BCE) do we see archaeological evidence for language, art, and religion—the precursors of modern humanity and therefore modern horror. These first humans are believed to have lived in small, family groups, sustaining themselves by foraging and hunting. During this age, the wandering bands of hunter-gatherers viewed the world through a prism of supernaturalism, wonder, and awe—a situation that hardly changed when they settled down to farm. Nevertheless, the wild was a terrifying place, full of powerful animals, violent weather, and irrational happenings of all kinds. The early humans who painted animals on the walls of caves, like those at Lascaux, and their successors who set up stones, like those at Stonehenge, all across the Neolithic (8,000 BCE to 3,000 BCE) landscape did so to cast in a permanent way the mythologies that sustained them. They wanted to give form to the shadows in their minds. Scholars like Dolf Zillman and Rhonda Gibson see in these ancient people the origins of horror fiction, people who told stories about gods, demons, and wild animals—the source of fear. But they dismiss the potent horror of the ancient world as something less than real, deliberate lies that were “products of the human imagination, driven by fear and narcissism.” Our ancestors, they speculate, “exaggerated” the world’s horrors because tales of monsters and demons were useful for “controlling believers,” a process of manipulation and control that continues to this very day [n.5]. This is, however, a cynical and reductive approach.

According to David Lewis-Williams and David Pearce, the neurological structure of our brains leads us to understand the cosmos as a set of stacked layers, roughly equivalent to the Christian view of hell, earth, and heaven. Humans live somewhere in the middle of this great stack of planes of existence, with the levels of heaven, light, and the gods usually located above the plane of the earth; and the levels of the underworld, darkness, and demons usually located in the planes below earth. For our purposes, we are most concerned with the malevolent hell dimensions envisioned as existing beneath our very feet.

This multi-level depiction of the universe is consistent across the world and through the ages, from our Paleolithic ancestors to today. It derived from the essential characteristics of the evolving human mind. Lewis-Williams and Pearce further argue that our biochemistry induces us to experience “neurologically generated mystical states” [n.6] as a realm of the supernatural, whose basic manifestations—vast caverns of geometric shapes, vortices, animals, and monsters—remain consistent across space and time, though the way they are experienced is governed by cultural expectations. This, they argue, is most apparent during altered states of consciousness brought about by sensory deprivation, trances, hallucinogenic drugs, or a number of other causes. It is during these conditions that humans experience the supernatural, the infernal, and the divine. But when in this state, what one culture may experience as a benign animal guide or an angel another may view as a hideous chimera grotesquely mingling human and animal, or even a demon or devil. The same process occurs during periods of transition between wake and sleep, periods when the ancients saw incubi and succubae and very modern people experience the supernatural in the form of alien abductions; that is, space monsters in an intergalactic spirit realm.

In ancient cultures, and in some traditional cultures today, there was a guide to the strange and frightening realm of the supernatural—the shaman, popularly known as the “witch-doctor” or “medicine man.” Shamanism was humanity’s first religious belief system, and it involved the understanding that chosen individuals could transcend this world to interact with the spirit world on behalf of others. To become a shaman, an individual had to be equipped with knowledge, sanctified and handed down from time immemorial, that allowed the shaman to enter the world of the supernatural, interact with the beings found therein, and therefore influence the course of events on earth. The shaman had the power to venture from plane to plane—between heaven, earth, and hell. So too did he have the power to change shapes and to take on animal form. But the transition from this world to the netherworld was not without its cost, and the shaman experienced great pain and stress in his travels. Further, there was always the chance that the shaman would not return to this world: “The danger is present, too, in the malevolence of certain spirits, and the shaman may have to do battle with inimical forces which have stolen the souls of the sick.” [n.7]

Here, then, in the first spiritual system devised by humankind do we see the same dark forces that would haunt human dreams for millennia to come. The shaman alone could stand against the horror because of the special knowledge he and his ancestors had gathered, and it was this sacred knowledge that was his protector against the darkness, a protector against the monsters.

But not all monsters existed in the human mind. Early humans encountered gigantic animals, such as the wooly mammoth or Gigantopithecus, the ten-foot-tall gorilla-like creature, both of which died out at the end of the last Ice Age, around ten thousand years ago. Memories of these monsters filtered down through the ages, and the bones of these beasts, and even the long-extinct dinosaurs, may well have given rise to mythology’s early monsters [n.8]. Dragons, for example, bear an uncanny resemblance to the skeletons of dinosaurs; and wooly mammoth bones resemble human bones enough to be confused for the remains of giants—so much so that the Romans used to set them up in their temples as relics of the lost race of giants. In a world before science, there was no way to know whether the skeletons of “dragons” and “giants” were not indicative of still greater horrors lurking in the forests beyond civilization, and knowledge of these creatures—however mythological or spurious—was a precious and protective commodity. This extended to the monsters presumed to live in the diabolical realms beyond the earth.

As Lewis-Williams and Pearce discuss, early mythologies show how the knowledge of the spirit realm, and how to win its rewards and avoid its terrors, became the possession of a sacred priesthood who monopolized this valuable wisdom. In the ancient Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, the title hero Gilgamesh, for instance, was said to have journeyed across the known world for knowledge of how to live forever, though he failed in his quest. In the world of Gilgamesh, religion, “founded on access to other realms,” had already become institutionalized, the sacred knowledge of light and dark already restricted to an elite who alone could mediate between humanity and the Others [n.9].

The ancient Greeks, too, knew all about this mixture of darkness and light, the way knowledge can hold back the shadows but ultimately destroys the very souls who wield its power. They expressed this eloquently in the myth of Prometheus, the Titan who in Greek cosmology created humanity in the earliest days of the earth. Prometheus—whose name itself means “foresight”—endowed his creation with the ability to think, to reason, and to know. He went still further and taught the first men the arts of civilization, imparting to them the wisdom of the gods themselves. Impudently, Prometheus carried himself to the heights of Mount Olympus, the home of the gods, and seized fire from the divine sanctuary, bringing the precious flame of life and light, forevermore a symbol of knowledge, to the cold and hungry humans cowering in the darkness below.

Prometheus gave humanity knowledge, but in so doing he trespassed on the will of Zeus, king of all the gods, who undertook to punish the Titan for his sins. Worst of all, Prometheus had still more knowledge, the possession of which would destroy the very fabric of the universal order, for Prometheus knew which of Zeus’s paramours would bare him a son powerful enough to overthrow his father and establish a new cosmological order. But Prometheus refused to tell, and Zeus had Prometheus chained to a rock on Mount Caucasus, where each day a vulture (though some say an eagle) swept down from the sky to eat his liver. As a god, Prometheus could not die, and his liver grew back as soon as the bird finished its unwholesome meal. Nevertheless, Prometheus was made to suffer endlessly until such a day as a descendent of Io would free him from his torments. Thus was knowledge the cause of pain, but its endurance made Prometheus a hero, as the poet Aeschylus made the god say in Prometheus Bound:

Known to me, known was the message that he

Hath proclaimed, and for none is it shameful to bear

At the hands of his enemies evil and wrong.

So now let him cast, if it please him, the two-

Edged curl of his lightning, and shatter the sky

With his thundering frenzy of furious winds;

Let the earth be uptorn from her roots by the storm

Of his anger, and Ocean with turbulent tides

Pile up, till engulfed are the paths of the stars;

Down to the bottomless blackness of Tartarus

Let my body be cast, caught in the whirling

Waters of Destiny:

For with death I shall not be stricken! [n.10]

Such is the essence of the Greek tragic hero, for whom the depths of misery is the possession of unsanctioned knowledge. Prometheus was not alone in the tragedy of knowing too much. The Greeks told also of Tereisias, the blind prophet who prophesied too well, revealing what the gods wished to remain hidden. For this he was tormented by Harpies, who fouled his food and menaced him until Jason and the Argonauts released him from his fate. Oedipus had the opposite problem, for his lack of knowledge led him to fulfill a prophecy that he would kill his father and take his mother for a wife. When he learned the truth, the knowledge was too much for him, and he blinded himself.

So, too, is the Judeo-Christian tale of Adam and Eve another example of the dangerous consequences of knowing too much. In Eden God set up trees to provide the first humans with food, but God also created a serpent who tempted Eve with the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge:

Now the serpent was more subtil than any beast of the field which the LORD God had made. And he said unto the woman, Yea, hath God said, Ye shall not eat of every tree of the garden? And the woman said unto the serpent, We may eat of the fruit of the trees of the garden: But of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of the garden, God hath said, Ye shall not eat of it, neither shall ye touch it, lest ye die. And the serpent said unto the woman, Ye shall not surely die: For God doth know that in the day ye eat thereof, then your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil. And when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was pleasant to the eyes, and a tree to be desired to make one wise, she took of the fruit thereof, and did eat, and gave also unto her husband with her; and he did eat. And the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together, and made themselves aprons. (Genesis 3:1-6)

This forbidden fruit of the Tree of Knowledge—the act of knowing—caused the Fall of Man, and God was none too happy with his creation’s discovery of knowledge that God had intended to let rot on the vine:

Unto the woman he said, I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee. And unto Adam he said, Because thou hast hearkened unto the voice of thy wife, and hast eaten of the tree, of which I commanded thee, saying, Thou shalt not eat of it: cursed is the ground for thy sake; in sorrow shalt thou eat of it all the days of thy life; Thorns also and thistles shall it bring forth to thee; and thou shalt eat the herb of the field; In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground; for out of it wast thou taken: for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return. … And the LORD God said, Behold, the man is become as one of us, to know good and evil: and now, lest he put forth his hand, and take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live for ever: Therefore the LORD God sent him forth from the garden of Eden, to till the ground from whence he was taken. So he drove out the man; and he placed at the east of the garden of Eden Cherubims, and a flaming sword which turned every way, to keep the way of the tree of life. (Genesis 3: 16-24)

Exiled from Eden, the price of knowledge was eternal toil and the sorrow and tragedy—yes, the horror—that darkens human life. Surely there is a poignancy in God’s lament that Adam has “become as one of us,” a recognition that the burden of knowledge is not one to be lightly shared. However, this tale is not a true horror story in our sense of the word, since this passage evokes only feelings of sadness, loss, and despair. It is closer to what we mean by horror than Prometheus was, but its purpose was not to frighten or terrify.

Nevertheless, the two tales of Prometheus and Eden laid the mythological foundation for what would become the Western tradition of the horror story, our modern mythology and a genre tied uniquely to a single source of ultimate horror, the very act of knowing, itself the defining characteristic of being human. However, the ancient world never developed horror tales in our sense of them; that had to wait for another more modern time. But before we explore this, we must first ask what we mean when we talk about “horror stories.”

What is Horror?

The horror story as we know it today is a unique product of Western culture and a sort of ersatz mythology, one whose rise came in tandem with the development of the West’s major contribution to world culture: modern science. Every society has its tales of supernatural menace, but it was in the West at the end of the eighteenth century that the horror story found its voice and flourished as a unique metaphor for the displacement from the past, from tradition, and from culture that modern science ushered in with its rapid development and promotion of change. Though this particular mood would spread outside the West, perhaps most prominently in Japan, it was Western civilization that gave birth to the horror genre in its modern form.

Literature responded to scientific progress in two ways: Science fiction represented our hopes and aspirations, the Golden Age that Progress was to bring. But if science fiction represented our dreams, horror art in all its myriad forms crystallized our nightmares, the dark fears that fester beneath the surface. Even science fiction concealed a quiet undercurrent of horror, often disguised under the name “fantastic literature,” or later, “the weird tale.” It was the soot on the shining citadel of Progress. Many science fiction scholars claim that sci-fi is a cognitive and philosophical genre while horror is purely emotional, with the implication that this is a lesser state [n.11]. This view is only half true, for it is the feeling of fear that most clearly defines what we mean when we talk of “horror” stories. But horror has its own philosophy and cognitive pleasures, as we shall see.

The emotion of horror is a combination of fear and revulsion, and it is related closely to terror, a feeling of fear and anxiety. When we speak of “horror” as a genre, we are often referring to the whole range of feelings related to the emotion of horror, as well as dread, discomfort, revulsion, fear, and terror. Of course this is not the same fear one feels when faced with a real-life fright, but the same emotional working we feel when we cry at a tragedy or laugh at a comedy. In the case of horror that artistic emotion is fear.

Many scholars do not recognize horror as a distinct genre but prefer to see it as a subset of the fantasy and science fiction genres (though, in its Gothic form, it predates and inspired both), or to call all three areas “speculative fiction.” Others, like Noël Carroll, define the horror genre as a body of stories that revolve around a “monster” that must be evaluated and which does not conform to current scientific beliefs. Carroll, for example, rejects stories of psychological horror, creepiness, or cruelty as falling outside horror’s true intent: monsters that challenge scientific understanding [n.12]. On the other hand, the noted critic Edmund Wilson believed that only psychological horror represented truly worthy horror fiction, while horror focused on the existence of monsters and ghosts was merely childish.

I believe that the horror genre can reasonably be expanded to include the entirety, from the unknown to monsters to well—known terrors like serial killers or mental illness—and that all are related to the knowledge and science. While it is true that horror does not have a more or less uniform set of trappings like sci-fi or westerns do, I believe it is a genre unto itself, one whose animating feature is neither setting nor plot nor even the presence of an indescribable monster but instead the feeling of fear.

Stephen King proposed that “horror” exists on three levels: The greatest horror stories aim for terror, a purely mental state of anticipatory fear at an unknown or unseen evil; lower down falls “horror,” a combination of mental fear and physical revulsion at a known evil; at the bottom of the heap is pure revulsion at a disgusting or otherwise distasteful occurrence [n.13]. Horror fiction—in whatever medium—explores these feelings of fear, revulsion, and dread. But delineating exactly where the boundaries for horror fiction fall is a notoriously tricky business, and one that requires a little bit of explanation and discussion. Let us begin by suggesting an outline for some of the major categories of horror:

Supernatural Horror

The most common type of traditional horror story (and the one Noël Carroll had in mind) involves a supernatural menace, such as a ghost, a vampire, or some other monster. The horror of the story derives from the fear and revulsion the protagonist feels upon encountering the supernatural. This is the realm of the witch, the werewolf, the ghost, and the vampire. Celebrated works in this arena include Bram Stoker’s Dracula (vampire) and Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House (ghost).

Weird Tale

The weird tale is a particular subset of horror fiction that draws from supernatural horror and dark fantasy (see below) but hints at greater terrors. The horror of the story derives from the realization by the protagonist or the reader that natural law has been violated and that powers beyond our comprehension are at work. As the celebrated writer of weird tales, H. P. Lovecraft, explained: “A certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; and there must be a hint, expressed with a seriousness and portentousness becoming its subject, of that most terrible conception of the human brain—a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space” [n.14]. Other writers of weird tales include Algernon Blackwood, Arthur Machen, and Ramsey Campbell.

Contes Cruelles

Contes cruelles are straightforward tales of suffering, cruelty, and physical pain, fear, and torture. They do not include supernatural elements but instead derive their horrors from the gruesomeness of the punishments they visit on their characters, often at the hands of serial killers or psychopaths, and the psychological impact on both victim and audience. Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Pit and the Pendulum” is an example of this, as are the various iterations of the Saw and Hostel movie franchises.

Psychological Horror

Similar to the contes cruelles, psychological horror frequently dispenses with supernaturalism to concentrate on horrors grounded in the real world. Unlike the contes cruelles, however, psychological horror locates the source of horror in the mind of the psychopath, serial killer, or other villain. It is the villain’s motivation for causing suffering that provokes the fear response. The prototype of this school of horror was Robert Bloch’s Psycho and its Hitchcock film counterpart.

Dark Fantasy

The term “dark fantasy” is sometimes used as a synonym for supernatural horror and at other times refers to horror stories set in sword-and-sorcery realms usually associated with Lord of the Rings-style fantasy literature. Dark fantasy is a nebulous term that currently describes works straddling the border between supernatural horror, science fiction, and high fantasy. It draws elements from all these genres and can include mythological landscapes and creatures. H. P. Lovecraft is often included in this genre, as is The Vampire Chronicles’ Anne Rice and Poppi Z. Brite.

Science Fiction

Horror is often found in dark works of science fiction, and science fiction trappings are often used in horror stories. As a result the line dividing sci-fi from horror is a blurry one, and works like John Campbell’s “Who Goes There?” (made into the two film versions of The Thing) or Philip K. Dick’s darker writings could sit in either category. The film Alien is a horror story even though it is set in outer space.

Other Genres

Other genres not normally associated with the supernatural or science fiction can include elements of horror as well; in fact, horror can occur in almost any type of art. The Lifetime network, for example, has developed an entire category of women-in-peril television movies that draw on elements of horror even as they cleave to the structures of the domestic drama. Harlequin Books, too, has a line of horror-romances in which one or both partners in a relationship is a supernatural creature. Even Scooby-Doo manages to include horror elements while taking the form of a Saturday-morning cartoon comedy.

Of course, these categories overlap with each other and cross-fertilize at will. It is often difficult to assign a work to one category or another, and some cut across all of them. For example, where should Frankenstein fall? Is it supernatural because it features a monster, a weird tale because it violates natural law, or science fiction due to its medical trappings? Perhaps it is dark fantasy or even primarily psychological, since both book and film attempt to rationalize the monster and make him a sympathetic figure. I have chosen to view “horror” broadly rather than categorize too carefully, and I will view all of the above as aspects of “horror.”

For our purposes, I will use the term “horror” to cover stories in a variety of media and genres whose primary aim is to elicit feelings of fear, terror, revulsion, or dread. Although I will focus primarily on supernatural horror, the weird tale, and psychological horror, I will discuss fantasy, science fiction, and other genres when they stray into the territory of horror. I will also focus primarily on Anglo-American horror fiction, with occasional examples from other cultural horror traditions, mostly because this is the story of horror in the Western tradition and partially because the majority of horror can be found in English-speaking countries. Lastly, to keep things simple, I will use the term “horror” to refer to horror tales in a variety of media, rather than the more pretentious term “horror art” which is often used to discuss horror fiction, cinema, comics, television, gaming, etc. all together. I think that sticking with “horror” is a simpler and more effective term, and when clarification is needed we always have the medium-specific names (e.g. “horror comics”) to fall back on.

I will also propose a loose framework for understanding the phases of horror as the genre grew and developed over time, beginning with the creation of the horror genre with the Gothic writers of the late eighteenth century. (Prior to this date, while there were scary stories, there was no genre of horror.) These periods are dominated by themes reflecting the concerns of the eras of their creation, and these themes are related to the intellectual developments of the age. The periods are not discrete, however, so while one theme may dominate in a certain time period, it often emerges before its period of dominance and fades away while another theme rises in its place. For example, by my count, in the 1890s one could find examples of evolutionary, spiritualist, and cosmic horror all at the same time. Therefore, the dates I propose here are overlapping and only approximations. Gothic fiction, for example, still has its advocates even two centuries after its dominance of the horror genre faded.

Gothic Horror (c. 1750 – c. 1845)

This period covers the early history of horror at the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth, a time when horror looked back to an imagined past of castles and monsters. Including landmarks of the genre ranging from the Gothic masters (Walpole, Radcliffe, etc.) to Edgar Allan Poe, this period was dominated by the Romantic reaction to Enlightenment materialism and rationalism, as horror literature attempted to explore the negative consequences of Enlightenment values.

Biological Horror (c. 1815 – c. 1900)

Nineteenth century “biological” horror begins with Shelley’s Frankenstein and includes horror classics like Stoker’s Dracula, Stevenson’s Jekyll and Hyde, and Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau. Nineteenth century horror reacted to the development of the life sciences, especially the theory of evolution and the invention of psychoanalysis. The period’s horror literature presaged, digested, and metamorphosed scientific developments to produce the most important period in horror.

Spiritualist Horror (c. 1865 – c. 1920)

The rapid technological development and concurrent development of pseudoscience before the First World War was reflected in horror’s preoccupation with ghosts and hauntings—a particular theme reflecting a discontent with scientific progress and the negative consequences of uncovering “forbidden” and “unnatural” knowledge. Photography and spiritualism contributed to the development of horror in this era as the genre incorporated and colonized the new sciences to produce its unique art.

Cosmic Horror (c. 1895 – c. 1945)

The development of “cosmic horror” occurred in reaction to the changing scientific understanding of the universe in the wake of Einstein’s theory of relativity, as exemplified in H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos and H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. Victorian supernatural horror transformed into extraterrestrial and transdimensional cosmic horror, positing alien invasions and powers outside material space, which helped to create a nightmare vocabulary with which to explore the results of a relativistic and atheistic cosmos.

Psycho-Atomic Horror (c. 1940 – c. 1975)

Following World War II science became institutionalized and gradually infiltrated most aspects of life, and horror—now represented by cinema and television as well as the written word and comic books—reflected the increasingly science-based society in which it thrived. This resulted in a rash of 1950s mutant monster movies, the invasion of extraterrestrials into the public consciousness, and the psychologizing tendency of horror like Robert Bloch’s (and Hitchcock’s) Psycho that sought to explain horror through the tools of modern science. It was, in short, the application of reason to rationalize irrational horror.

Body Horror (c. 1965 – c. 2000)

The period following the 1960s was an era defined by increasing reproductive freedom, biotechnological advances, and an increased turn toward “body horror”—the ritual mutilation of the human body (e.g. “slasher” films, vampires, splatterpunk). This development correlated with scientific discoveries in contraception, infertility treatments, medicine, and biotechnology in which the body became the source of horror. Highlights of the era include The Omen, The Exorcist, Alien, the 1980s slasher films, and the emergence of horror online and in the gaming world.

Horror of Helplessness (c. 1990 – present)

As the twentieth century Cold War order broke down into a postmodern, fractured, and violent aftermath, horror’s focus shifted away from institutional science toward a different form of knowledge, the revelation of hidden truths and the breakdown of absolute truth. Horror also reflected the uncertain fate of free will in a time when science reduced the human mind and soul to a series of genetic and neurological imperatives over which humans had little control. In works like Buffy the Vampire Slayer or Elizabeth Kostova’s The Historian, knowledge has become a weapon wielded in defense of one’s beliefs. In Saw and its ilk, fatalism turned to graphic and extreme violence.

This book will examine each of these period sequentially by looking at the scientific and cultural background of the period, its expression in literature, and its expression in the visual and performing arts. Doing so will allow us to trace the impact of developments in science and philosophy on the horror genre and demonstrate the way horror uniquely reflected the role of knowledge in a changing Western world.

Entering the World of Horror

Let us take for our guide in our exploration of horror and knowledge a man for whom knowing became the last and greatest horror, a certain Dr. Faust, late of Germany and Hell, a man whose intertwining themes of knowledge and damnation shall follow us through our journey into the heart of horror. An early sixteenth century vagabond necromancer, magician, and juggler going by Dr. Johann Faust of Heidelberg provided the outline for the legendary character that would bear his name, an amalgamation of a number of medieval necromancers remade into a new character, a man who sold his soul to the Devil for the price of knowledge [n.15]. The original Faust was more charlatan than sorcerer, an accomplished liar and trickster who claimed communion with demons as a way of making a living. As the English playwright Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593) put it in his Tragical History of Doctor Faustus* (1604):

falling to a devilish exercise,

And glutted now with learning's golden gifts,

He surfeits upon cursed necromancy [n.16]

The Faust (or the Latinate Faustus) legend originates at the end of the sixteenth century with a 1587 “biography” (the Faustbuch) published in Frankfurt which combines a number of medieval folk tales about wizards and Satan-worshippers retold as Faust tales. Translated into English in 1592, it was read by Marlowe, who based his famous play on it. In the play Marlowe invests Faust with the trappings of classical tragedy, giving shape and form to the legends that circulated throughout the Continent, some of which are still told today. He also includes a great deal of religious imagery and appeals to Christ and to God, typical of the piety of Elizabethan England, and a fair amount of blood, typical of the violent and graphic Elizabethan and Jacobean stages.

In Marlowe’s telling, full of hubris, John Faustus exhausts his studies of earthly knowledge, mastering medicine, philosophy, and astrology. A keen intellect, he wishes for more. He wants the very power of the gods, accessible through the forbidden knowledge of the necromancers:

These metaphysics of magicians

And necromantic books are heavenly;

Lines, circles, scenes, letters, and characters,

Ay, these are those that Faustus most desires.

O what a world of profit and delight,

Of power, of honour, of omnipotence

Is promis’d to the studious artisan! [n.17]

For Faustus, knowledge is power, and he is willing to do anything to obtain this knowledge. He summons a demon from hell to do his bidding. This is Mephistopheles, servant to Lucifer himself. Faustus and Mephistopheles make a deal whereby the demon agrees to serve Faustus for twenty-four years and provide him with all the knowledge he could desire in exchange for Faustus’ eternal soul. Faustus forces the demon to tell him the secrets of astronomy and astrology, and he learns the dark arts of calling up the shades of the dead to seize their lost secrets. Even Lucifer himself arrives to present Faustus with a book of demoniac knowledge.

After many adventures, Faustus’ hour comes, and the Devil and his minions arrive to take Faustus down to Hell:

My God! My God! look not so fierce on me!

Adders and serpents, let me breathe awhile!

Ugly hell, gape not! come not, Lucifer!

I'll burn my books!—Ah, Mephistophilis! [n.18]

Faustus, though, cannot bring himself to renounce his learning in favor of complete submission to God and his revealed truths, so Hell swallows him after a number of soliloquies in which Faustus wrestles with himself over his inability to forgo science in favor of faith. The Chorus sums up the lesson we are meant to take from the over-learned Faustus’ damnation:

Cut is the branch that might have grown full straight,

And burned is Apollo’s laurel bough,

That sometimes grew within this learned man.

Faustus is gone; regard his hellish fall,

Whose fiendful fortune may exhort the wise,

Only to wonder at unlawful things,

Whose deepness doth entice such forward wits

To practice more than heavenly power permits. [n.19]

Or, in other words, knowing too much is deadly; and like God exiling Adam and Eve or Zeus smiting Prometheus, there are things the divine does not wish for humanity to know.

Keeping mindful of Faustus’ fate, let us venture forth and explore the world that followed Faustus, a world whose deep superstitions and emerging scientific world-view created the conditions that yielded the first true works of what we would consider pure horror. It was the era of Renaissance and Reformation, giving way to Enlightenment, to reason, and (of course), to horror: A world where witches lived side-by-side with scientists, and superstition and science were not yet separate.

Notes

1. H. P. Lovecraft, The Annotated Supernatural Horror in Literature (New York: Hippocampus, 2000), 21.

2. Walter Evans, “Monster Movies: A Sexual Theory,” Journal of Popular Film 2, no. 4 (1973): 353-365; Richard K. Sanderson, “Glutting the Maw of Death: Suicide and Procreation in ‘Frankenstein’,” South Central Review 9, no. 2 (Summer 1992): 49-64;Joan Copjec, “Vampires, Breast Feeding, and Anxiety,” October, 58 (Autumn 1991): 24-43.

3. David J. Skal, The Monster Show, rev. ed. (New York: Faber and Faber, 2001), 339.

4. Ibid., 277.

5. Dolf Zillmann and Rhonda Gibson, “Evolution of the Horror Genre,” in Horror Films: Current Research on Audience Preference and Reactions, edited by James B. Weaver III and Ron Tamborini (Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1996), 15-16.

6. David Lewis-Williams and David Pearce, Inside the Neolithic Mind (London: Thames & Hudson, 2005), 26.

7. Miranda and Stephen Aldhouse-Green, The Quest for the Shaman (London: Thames & Hudson, 2005), 12.

8. Adrienne Mayor, The First Fossil Hunters (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001); Adrienne Mayor, Fossil Legends of the First Americans (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005).

9. Lewis-Williams and Pearce, Inside the Neolithic Mind, 159.

10. Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound, trans. George Thomson (New York: Dover, 1995), 45-46.

11. Barry Keith Grant, “‘Sensuous Elaboration: Reason and the Visible in the Science Fiction Film,” in Alien Zone II: The Spaces of Science Fiction Cinema, ed. Annette Kuhn(London: Verso, 1999), 17.

12. Noël Carroll, The Philosophy of Horror; or, Paradoxes of the Heart (New York: Routledge, 1990), 15.

13. Stephen King, “Some Defining Elements of Horror,” Danse Macabre, in Horror, ed. Michael Stuprich (San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 2001), 34-45.

14. Lovecraft, Supernatural Horror in Literature, 23.

15. Kuno Franke, “The Faust Legend,” in Lectures on the Harvard Classics, ed. William Allan Neilson et al., vol. 51 of Harvard Classics, ed. Charles W. Eliot(New York: P. F. Collier & Son, 1909-1914), Bartelby.com, 2001, <http://www.bartleby.com/60/204.html> (15 October 2006).

16. Christopher Marlowe, Doctor Faustus (New York: Dover, 1995), 1.

17. Ibid., 4-5.

18. Ibid., 56.

19. Ibid.

"Introduction" is excerpted from Knowing Fear: Science, Knowledge, and the Development of the Horror Genre by

Jason Colavito (McFarland, 2008). This work is copyright © 2008 Jason

Colavito. All rights reserved. Reproduction is prohibited without the

express written permission of the author and McFarland.