Carl Christian Rafn

1839

|

NOTE |

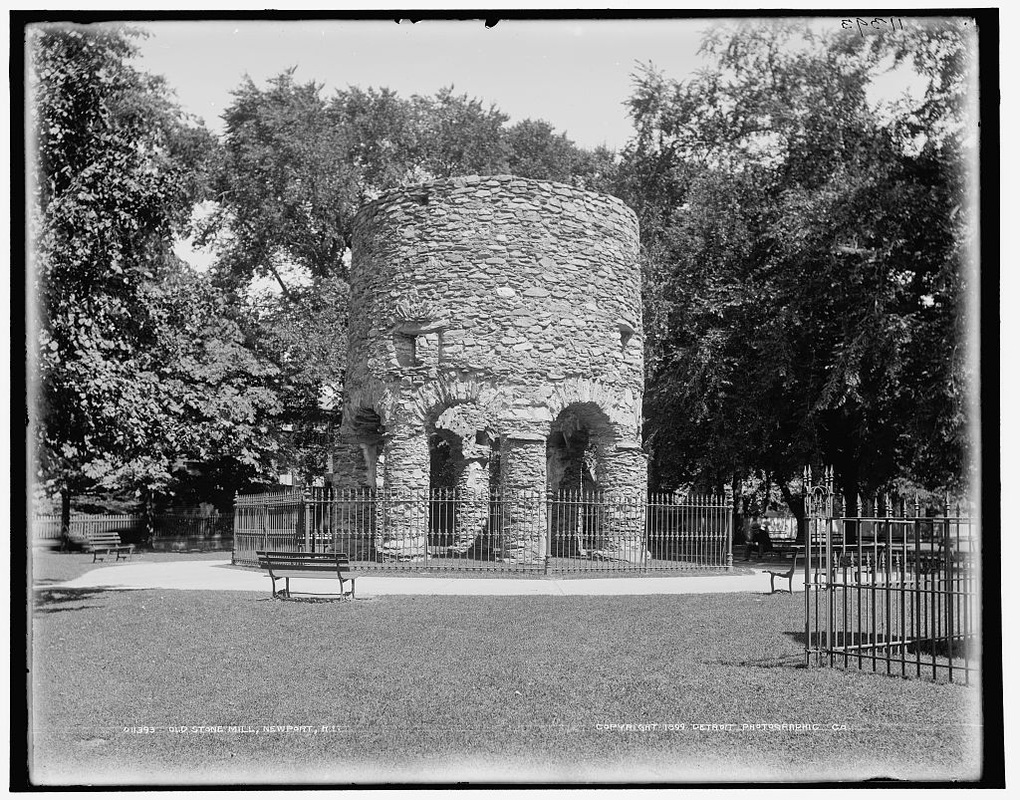

The Newport Tower is a seventeenth century windmill located in Newport, Rhode Island. However, the Tower has been a staple of diffusionist literature for more than 170 years, cited as evidence of trans-oceanic contact in medieval times or earlier. Wild claims about the tower derive ultimately from the work of CARL CHRISTIAN RAFN (1795-1864), a Danish antiquarian who was convinced that the Norse had colonized America based upon his readings of the Norse literature. Rafn correctly deduced (and was the first to do so) that Vinland was in America, but he incorrectly placed it in New England rather than Newfoundland. As a result, when a correspondent sent him romanticized drawings of the Tower, which he never viewed in person, he saw in the site a reflection of twelfth-century Norse architecture. He was the first to make this claim. Compare the rough-hewn tower of the photograph with the smooth, finished-looking tower of Tab. III, and you can see how the drawings misled him.

Later writers have incorrectly stated that Rafn made his claim in his monumental Latin-language work Antiquitates Americanae (1831), but a review of this work finds that the only mention of the Tower is in a lengthy 1839 supplement, which, as far as I can tell, has never been reproduced. I am happy to present this key text for understanding one of alternative history's most persistent claims. This online edition is transcribed from the English language edition of the Supplement to the Antiquitates Amercanae published by the Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries in Copenhagen in 1841, reprinting the version contained in the Memoires de la Societe Royale des Antiquaires du Nord for 1839. |

SUPPLEMENT TO THE ANTIQUITATES AMERICANAE

ACCOUNT OF AN ANCIENT STRUCTURE IN NEWPORT, RHODE-ISLAND, THE VINLAND OF THE SCANDINAVIANS,

communicated by Thomas H. Webb, M. D., in letters to Professor Charles C. Rafn; with remarks annexed by the latter.

communicated by Thomas H. Webb, M. D., in letters to Professor Charles C. Rafn; with remarks annexed by the latter.

Boston May 22, 1839.

In the town of Newport, near the Southern extremity of the island of Rhode-Island, stand the ruins of a structure, bearing an antique appearance, known to the inhabitants and to the numerous visitors, who flock there in the summer season, from various quarters of the Union to enjoy the pure air and the luxury of seabathing, by the homely appellation of the OLD STONE MILL.

It is situated on the west side, (near the summit), of the hill, upon which the upper part, or rear of the town is built, and is so placed as to command a view of the noble harbor, that lies to the West. This has, for a long time, been an object of wonder to beholders, exciting the curiosity of all who visit it, and giving rise to many speculations and conjectures, among both the learned and the unlearned. But nothing entirely satisfactory has ever been decided about it; it still remains shrouded with mystery; and the only reply that can be obtained to any interrogatory, addressed even to the oldest inhabitants, is that “from the time that the memory of man runneth not to the contrary it has been styled the Old Stone Mill.”

Every thing about it, as many think, throws discredit upon the supposition that it was erected for a Mill, although from what we can gather we doubt not but that it may have been at some period used as such. No similar structure built in ancient or in modern times, for any purpose whatever, is to be met with in the vicinity referred to, nor indeed, so far as we have any reason to believe, in any other section of this Country. The State of Rhode-Island was first settled by the whites in Post-Columbian times, (using that expression, by way of distinction from the Ante-Columhian times, as, since the satisfactory evidence that has been adduced of the early visits of the Northmen, it would be manifestly incorrect to speak of the period we are now referring to, as that in which the first white settlers located themselves here,) we repeat, the State of Rhode-Island was first settled by the whites or Europeans, in Post-Columbian times in the year 1636. Providence was founded at that period, and was so named by its founder, Roger Williams, in token of God’s peculiar care of him, when he fled from his brethren in a neighboring Colony, in consequence of persecution for conscience’s sake, and here amid the savages of the wilderness, (who proved themselves friends to him,) proclaimed to all, and maintained for all, entire freedom of opinion in matters of religious concernment. Two years after, viz. in 1638, the island of Rhode-Island, having been purchased of the Indians, was settled; — first at the Northern end, and subsequently at the Southern, that is to say at Newport.

The earliest manuscript record, wherein an allusion is made to the stone structure, is the Will of Governor Benedict Arnold; this was executed in 1678 being but 40 years from the settlement of the place. In this instrument it is alluded to, as his “stone built wind mill”. So that it will be observed, that even then it was denominated the mill as though it had been built, or at least used, for one.

The question may perhaps be asked, — “If this structure were here when the English first located themselves at Newport, would they not have taken particular notice and made especial mention of it?” But on the other hand it may be said, “If it were erected subsequently, is it not reasonable to suppose that such a remarkable transaction would have been duly chronicled?” — The singularity of erecting such a unique piece of architecture, at such a time, would have been noised far and wide throughout the Colonies, and some of the writers, who were taking due note of the events of the day to transmit to the mother country, or for the information of those dwelling in the land of their adoption, would certainly, we should suppose, have penned a line or two in reference to the strange building fancies of the Rhode-Islanders. That the neighboring inhabitants were not ignorant of passing transactions in the Island Colony is abundantly evident, and that they watched with a scrutinizing eye every thing that was there going on, cannot for a moment be doubted, knowing as we do that they entertained a great jealousy towards them. But we will not extend these remarks at present.

In investigations of this description we should, where there is any rational hope of success, examine into possibilities as well as probabilities. I therefore transmit, for your inspection, drawings of the structure, thinking it at least among the possibilities that your investigations relative to the early history of America and your acquaintance with ancient structures in the North may enable you to throw some light upon the matter; at all events in so far as to decide, if this be probably the work of a period more recent than that of the AnteColumbian settlement of this Country, which in fact I am inclined to think is the case, although my mind is not conclusively made up.

The drawings sent may be relied upon as accurate in all essential particulars, being copies from some taken expressly for me, by my friend F. Catherwood, architect, who is familiar with the relicks of bygone times, having spent years in wandering among the ruins of the East and in making researches in the Holy Land.

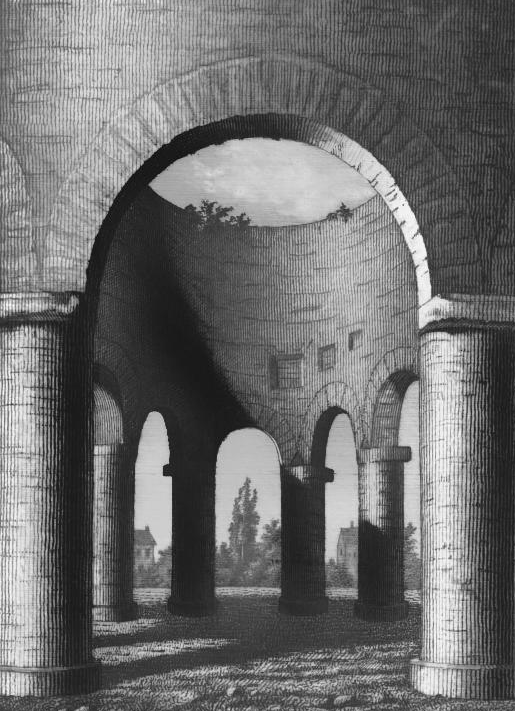

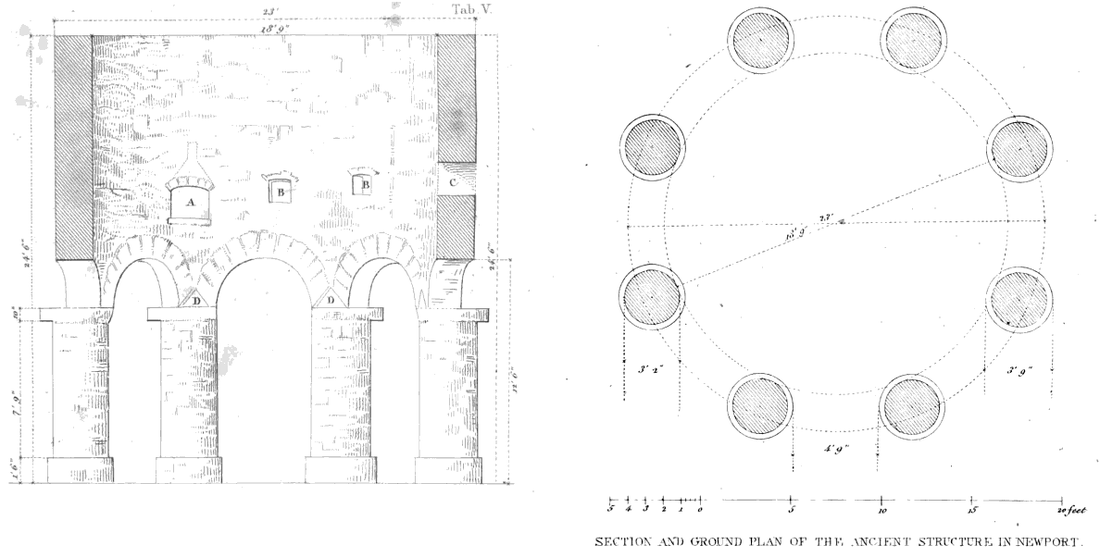

The drawings are four in number. The first (Tab. III) is an exterior view, and will convey a correct idea of the ruin as it now is. The second (Tab. IV) is a view of the interior. It is hardly necessary to observe that this is not strictly accurate, as regards relative proportions of the columns in the front and back ground, but it fully answers the purpose for which it was drawn. No. 3 is a section and No. 4 a ground plan of the structure. Both of these (Tab. V) are drawn from actual measurements and laid down upon a scale of English feet as marked on No. 4. In No. 3 A represents a fire place; B,B, recesses or cupboards; C, the section of a window; (of which there are three; viz. one towards the North, one to the South, and one to the West;) D,D are hollow places above the columns, in which we presume originally rested the ends of the timbers that sustained the floor. If so, however, there must have been two stories, in order to have made the recesses available. The space below, encircled by the columns, seems to have been entirely left open, and there does not appear to have been any rampart, ditch, or enclosure around the structure. [1]

The building is constructed of rough stone, (gray wacke, which abounds here,) laid in courses, and strongly cemented together by a mortar, composed of sand and gravel, which must have been of a most excellent quality, as it has become almost as hard as the stone itself. It looks as if once partially or entirely covered with cement, of a similar character with the mortar. Its height is 24 feet 6 inches, and was, we should think, originally somewhat greater. Its outer diameter is 23 feet, its inner is 18 feet 9 inches. It is built upon arches which rest upon eight columns. Its height from the ground to the centre of the arch is 12 feet 6 inches. The entire height of the columns is 10 feet l inch; viz: the base one foot 6 inches, the shaft 7 feet 9 inches, and the capital 10 inches; diameter at the base 3 feet 9 inches, above the base 3 feet 2 inches. The foundation extends under the columns to the depth of between 4 and 5 feet, from the surface of the ground.

There is nothing but the bare walls standing; neither rooting nor any portion of the interior fitting up remaining.

It is situated on the west side, (near the summit), of the hill, upon which the upper part, or rear of the town is built, and is so placed as to command a view of the noble harbor, that lies to the West. This has, for a long time, been an object of wonder to beholders, exciting the curiosity of all who visit it, and giving rise to many speculations and conjectures, among both the learned and the unlearned. But nothing entirely satisfactory has ever been decided about it; it still remains shrouded with mystery; and the only reply that can be obtained to any interrogatory, addressed even to the oldest inhabitants, is that “from the time that the memory of man runneth not to the contrary it has been styled the Old Stone Mill.”

Every thing about it, as many think, throws discredit upon the supposition that it was erected for a Mill, although from what we can gather we doubt not but that it may have been at some period used as such. No similar structure built in ancient or in modern times, for any purpose whatever, is to be met with in the vicinity referred to, nor indeed, so far as we have any reason to believe, in any other section of this Country. The State of Rhode-Island was first settled by the whites in Post-Columbian times, (using that expression, by way of distinction from the Ante-Columhian times, as, since the satisfactory evidence that has been adduced of the early visits of the Northmen, it would be manifestly incorrect to speak of the period we are now referring to, as that in which the first white settlers located themselves here,) we repeat, the State of Rhode-Island was first settled by the whites or Europeans, in Post-Columbian times in the year 1636. Providence was founded at that period, and was so named by its founder, Roger Williams, in token of God’s peculiar care of him, when he fled from his brethren in a neighboring Colony, in consequence of persecution for conscience’s sake, and here amid the savages of the wilderness, (who proved themselves friends to him,) proclaimed to all, and maintained for all, entire freedom of opinion in matters of religious concernment. Two years after, viz. in 1638, the island of Rhode-Island, having been purchased of the Indians, was settled; — first at the Northern end, and subsequently at the Southern, that is to say at Newport.

The earliest manuscript record, wherein an allusion is made to the stone structure, is the Will of Governor Benedict Arnold; this was executed in 1678 being but 40 years from the settlement of the place. In this instrument it is alluded to, as his “stone built wind mill”. So that it will be observed, that even then it was denominated the mill as though it had been built, or at least used, for one.

The question may perhaps be asked, — “If this structure were here when the English first located themselves at Newport, would they not have taken particular notice and made especial mention of it?” But on the other hand it may be said, “If it were erected subsequently, is it not reasonable to suppose that such a remarkable transaction would have been duly chronicled?” — The singularity of erecting such a unique piece of architecture, at such a time, would have been noised far and wide throughout the Colonies, and some of the writers, who were taking due note of the events of the day to transmit to the mother country, or for the information of those dwelling in the land of their adoption, would certainly, we should suppose, have penned a line or two in reference to the strange building fancies of the Rhode-Islanders. That the neighboring inhabitants were not ignorant of passing transactions in the Island Colony is abundantly evident, and that they watched with a scrutinizing eye every thing that was there going on, cannot for a moment be doubted, knowing as we do that they entertained a great jealousy towards them. But we will not extend these remarks at present.

In investigations of this description we should, where there is any rational hope of success, examine into possibilities as well as probabilities. I therefore transmit, for your inspection, drawings of the structure, thinking it at least among the possibilities that your investigations relative to the early history of America and your acquaintance with ancient structures in the North may enable you to throw some light upon the matter; at all events in so far as to decide, if this be probably the work of a period more recent than that of the AnteColumbian settlement of this Country, which in fact I am inclined to think is the case, although my mind is not conclusively made up.

The drawings sent may be relied upon as accurate in all essential particulars, being copies from some taken expressly for me, by my friend F. Catherwood, architect, who is familiar with the relicks of bygone times, having spent years in wandering among the ruins of the East and in making researches in the Holy Land.

The drawings are four in number. The first (Tab. III) is an exterior view, and will convey a correct idea of the ruin as it now is. The second (Tab. IV) is a view of the interior. It is hardly necessary to observe that this is not strictly accurate, as regards relative proportions of the columns in the front and back ground, but it fully answers the purpose for which it was drawn. No. 3 is a section and No. 4 a ground plan of the structure. Both of these (Tab. V) are drawn from actual measurements and laid down upon a scale of English feet as marked on No. 4. In No. 3 A represents a fire place; B,B, recesses or cupboards; C, the section of a window; (of which there are three; viz. one towards the North, one to the South, and one to the West;) D,D are hollow places above the columns, in which we presume originally rested the ends of the timbers that sustained the floor. If so, however, there must have been two stories, in order to have made the recesses available. The space below, encircled by the columns, seems to have been entirely left open, and there does not appear to have been any rampart, ditch, or enclosure around the structure. [1]

The building is constructed of rough stone, (gray wacke, which abounds here,) laid in courses, and strongly cemented together by a mortar, composed of sand and gravel, which must have been of a most excellent quality, as it has become almost as hard as the stone itself. It looks as if once partially or entirely covered with cement, of a similar character with the mortar. Its height is 24 feet 6 inches, and was, we should think, originally somewhat greater. Its outer diameter is 23 feet, its inner is 18 feet 9 inches. It is built upon arches which rest upon eight columns. Its height from the ground to the centre of the arch is 12 feet 6 inches. The entire height of the columns is 10 feet l inch; viz: the base one foot 6 inches, the shaft 7 feet 9 inches, and the capital 10 inches; diameter at the base 3 feet 9 inches, above the base 3 feet 2 inches. The foundation extends under the columns to the depth of between 4 and 5 feet, from the surface of the ground.

There is nothing but the bare walls standing; neither rooting nor any portion of the interior fitting up remaining.

Boston Dec. 29, 1839.

Upon comparing the drawings sent before, with the original, which I had a hasty opportunity of doing, the past summer, whilst on a brief business visit to Newport, I find that they have a more finished appearance than what they should have. The columns have no regular capitals; the upper layer of stone projects a little beyond the others composing the shafts, and the columns stand out somewhat beyond the structure raised thereon. To give you a better idea of this, I send you a corrected copy [2] of No. 1.

The projection you will perceive is found only on the outer half of the columns, thus making, as it were, rude semicapitals; upon the inner side, the shaft of each from the base to the spring of the arch is a straight line. The window on No. 1 has slanting sides inclined towards each other, from without, inwards, thus giving it the appearance of an embrasure. It may have been thus constructed the better to admit light.

I have little to add to what has already been communicated to you respecting this ruin. It was heretofore stated that ever since it first attracted special notice, it has been called the “Old Stone Mill”. It was also mentioned that the earliest record we have of it, occurs in the Will of Governor Benedict Arnold which bears date A. D. 1678. The following are extracts from said Will.

“My body I desire & appoint to be buried at ye North East corner of a parcel of ground containing three rod square being of & lying in my land in or near the line or path from my dwelling house leading to my stone built wind mill in ye town of Newport above mentioned”. — Again: “I give & bequeath” &c. “ye other & greater parcel of ye tract of land above said upon which standeth my dwelling or Mansion House & other buildings thereto adjoining or belonging as also my stone built wind mill in ye said” &c.

These allusions certainly favor the idea that the building was erected for a mill, although to be sure they do not conclusively prove it. The structure might have been found here, and by Governor Arnold converted into a mill, as for such a purpose a moveable wooden top like that of a modern wind mill could easily have been raised upon it. Indeed some aged inhabitants of Newport who were living 8 or 10 years since spoke of its having been thus used in their early days.

It was also at one period called the Powder Mill; not however as we presume from gunpowder having been manufactured, but deposited, there, for safe keeping; in other words from having been used as a powder magazine. We subjoin the copy of a deposition relating to this and another point, recently furnished us.

“Mr. Joseph Mumford now residing at Halifax in the British Province of Nova Scotia, aged about eighty years, formerly of Newport, in the State of Rhode-Island, states that his father was born in the year 1699 in said Newport and that his father always spoke of the Stone Mill in this town as the Powder Mill, and that when he was a boy his father used it as a haymow — that there was a circular roof on it at that time and a floor above the arches — that he has himself when a boy repeatedly found powder in the crevices sometimes to the amount of two or three pounds, and has likewise known other boys to find quantities of it.”

Dated Nov. 17, 1834. Signed “Joseph Mumford”.

The period here alluded to was anterior to the Revolutionary war which commenced in 1775. This I mention, as some writers have erroneously stated that the structure was used as a magazine during the last war (1812).

It seems from the aforegoing deposition, that the hollow places D,D above the columns on No. 3, may have been made at the time this structure was used as a hay-mow, in order perhaps to place a flooring or platform as low as possible and thus obtain more storage room. So that the apparent want of wisdom in placing the recesses B,B (No. 3) so high, is removed, as the reasonable supposition now is, that the original flooring was elevated some feet above the centre of the arches.

Among the first settlers of Newport was Peter Easton, who was in the practice of noting down important events and transactions in the Colony. Under date of 1663 he writes:

“This year we built the first windmill”. As he enters into no particulars, it is evident to me that the first windmill by him alluded to, was a mere temporary building, and not the stone structure. The latter therefore, if originally a windmill, must have been erected at a later date. As formerly remarked by me, if found standing here, when Newport was first settled, it is singular that a man like Peter Easton should not have made mention of it; whilst on the other hand, if constructed afterwards, but yet in the early times of the Colony, as in that case it must have been, it is as singular considering the strifes and contentions of the times, and the animosities which prevailed between that and the neighboring Colonies, that the raising of such an unique pile did not attract the attention, excite the fears and call forth the animadversions of some writer of the period. View the subject as we may, difficulties will still meet us. It has perhaps occupied more of my time, and your attention than it really deserves. It was natural however, considering the doubts that exist, for me to direct your notice to it; as I reasonably conjectured, if there were any similarity between this structure and any in the North of Europe, supposed to have been erected about the time of the Scandinavian voyages, you would readily recognize it. The settling of the question, however it may be decided, will be advantageous, inasmuch as it will either advance us one step farther in our investigations, or by removing an obstacle aid in preparing the way for such advancement.

The projection you will perceive is found only on the outer half of the columns, thus making, as it were, rude semicapitals; upon the inner side, the shaft of each from the base to the spring of the arch is a straight line. The window on No. 1 has slanting sides inclined towards each other, from without, inwards, thus giving it the appearance of an embrasure. It may have been thus constructed the better to admit light.

I have little to add to what has already been communicated to you respecting this ruin. It was heretofore stated that ever since it first attracted special notice, it has been called the “Old Stone Mill”. It was also mentioned that the earliest record we have of it, occurs in the Will of Governor Benedict Arnold which bears date A. D. 1678. The following are extracts from said Will.

“My body I desire & appoint to be buried at ye North East corner of a parcel of ground containing three rod square being of & lying in my land in or near the line or path from my dwelling house leading to my stone built wind mill in ye town of Newport above mentioned”. — Again: “I give & bequeath” &c. “ye other & greater parcel of ye tract of land above said upon which standeth my dwelling or Mansion House & other buildings thereto adjoining or belonging as also my stone built wind mill in ye said” &c.

These allusions certainly favor the idea that the building was erected for a mill, although to be sure they do not conclusively prove it. The structure might have been found here, and by Governor Arnold converted into a mill, as for such a purpose a moveable wooden top like that of a modern wind mill could easily have been raised upon it. Indeed some aged inhabitants of Newport who were living 8 or 10 years since spoke of its having been thus used in their early days.

It was also at one period called the Powder Mill; not however as we presume from gunpowder having been manufactured, but deposited, there, for safe keeping; in other words from having been used as a powder magazine. We subjoin the copy of a deposition relating to this and another point, recently furnished us.

“Mr. Joseph Mumford now residing at Halifax in the British Province of Nova Scotia, aged about eighty years, formerly of Newport, in the State of Rhode-Island, states that his father was born in the year 1699 in said Newport and that his father always spoke of the Stone Mill in this town as the Powder Mill, and that when he was a boy his father used it as a haymow — that there was a circular roof on it at that time and a floor above the arches — that he has himself when a boy repeatedly found powder in the crevices sometimes to the amount of two or three pounds, and has likewise known other boys to find quantities of it.”

Dated Nov. 17, 1834. Signed “Joseph Mumford”.

The period here alluded to was anterior to the Revolutionary war which commenced in 1775. This I mention, as some writers have erroneously stated that the structure was used as a magazine during the last war (1812).

It seems from the aforegoing deposition, that the hollow places D,D above the columns on No. 3, may have been made at the time this structure was used as a hay-mow, in order perhaps to place a flooring or platform as low as possible and thus obtain more storage room. So that the apparent want of wisdom in placing the recesses B,B (No. 3) so high, is removed, as the reasonable supposition now is, that the original flooring was elevated some feet above the centre of the arches.

Among the first settlers of Newport was Peter Easton, who was in the practice of noting down important events and transactions in the Colony. Under date of 1663 he writes:

“This year we built the first windmill”. As he enters into no particulars, it is evident to me that the first windmill by him alluded to, was a mere temporary building, and not the stone structure. The latter therefore, if originally a windmill, must have been erected at a later date. As formerly remarked by me, if found standing here, when Newport was first settled, it is singular that a man like Peter Easton should not have made mention of it; whilst on the other hand, if constructed afterwards, but yet in the early times of the Colony, as in that case it must have been, it is as singular considering the strifes and contentions of the times, and the animosities which prevailed between that and the neighboring Colonies, that the raising of such an unique pile did not attract the attention, excite the fears and call forth the animadversions of some writer of the period. View the subject as we may, difficulties will still meet us. It has perhaps occupied more of my time, and your attention than it really deserves. It was natural however, considering the doubts that exist, for me to direct your notice to it; as I reasonably conjectured, if there were any similarity between this structure and any in the North of Europe, supposed to have been erected about the time of the Scandinavian voyages, you would readily recognize it. The settling of the question, however it may be decided, will be advantageous, inasmuch as it will either advance us one step farther in our investigations, or by removing an obstacle aid in preparing the way for such advancement.

_________

SUPPLEMENT TO THE ANTIQUITATES AMERICANÆ, by Charles C. Rafn.

(Translated by John M‘Caul, M.A. Oxford.)

(Translated by John M‘Caul, M.A. Oxford.)

In the Disquisitions, wherewith in the ANTIQUITATES AMERICANÆ I accompanied my edition of the Old Northern MSS relating to the Ante-Columbian history of America, I endeavoured to assign the position of those regions in that country, which were discovered by the Scandinavians in the 10th century, and of the places mentioned in the ancient accounts as having been frequented by them in the times immediately following the discovery. The situation of KIALARNES and FURDUSTRANDIR, as also of the VÍNLAND of the Northmen, is, as far as I can observe, no longer considered as doubtful. But having ventured to suggest as a probable conjecture, that the ancient Northmen not only made a settlement in those parts, but also continued to reside there during a considerable period — for several generations — it has been found difficult to reconcile this conjecture with the circumstance, that in the district in question there never has been found any building of a remote antiquity, “not a stone which appears to have been laid upon another stone, according to the principles of European Art”. This has appeared inexplicable, inasmuch as the very same people erected in Greenland edifices, of which numerous ruins to this day bear Witness of the race by whom they were constructed. To this it must, however, be observed that Greenland was entirely without woods, and consequently quite destitute of timber fit for the purpose of building. The ancient MSS inform us that the inhabitants used to procure drift timber from the North of Baffin’s Bay, and it would even seem from Lancaster Sound [3]. But the quantity so obtained must have fallen very short of what they required. They were obliged, therefore, to import this material partly from Norway, and in part also, as we find expressly stated, from Vinland [4]. From places so remote did the European inhabitants of Greenland fetch their building timber in the 11th century. Their increased acquaintance with America would doubtless at a subsequent period render it more easy for them to procure their supplies of this material, inasmuch as they could fetch it from countries situated nearer to their own, as for example, from Markland (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick or Lower Canada [5]) as is reported in the Annals of 1347. Still the supply obtained from these sources, must, from the difficulties attending its importation, have been very inadequate for the erection of the buildings themselves, and must have been nearly exclusively employed in the fitting up of the interior of their houses. Buildings, public as well as private, were therefore in Greenland erected of stone, necessity compelling the inhabitants to make use of the more accessible material, even although the working and employment of it required a greater degree of toilsome labour. Thus the church in Kakortok is built of stone obtained from the adjacent cliffs, as is still clearly perceptible in comparing those with the walls of that structure [6]. The same inference is confirmed by the rest of the ruins in Greenland. In Iceland on the other hand, where building timber was more easy to be procured, as also in Scandinavia itself, by far the greater part of the buildings were constructed of wood, and only a very few of stone, cathedral churches and a few castles forming almost the only exceptions. The employment of wood instead of stone, even in the erection of public buildings, has been adhered to in many parts of Norway down to the latest times, and even in our own days we find in many, if not in а great majority of instances, the country churches in Norway built of wood.

The earliest settlement in Vinland occurs in the 11th century, when wooden edifices were far more general than in the subsequent centuries [7]. The country abounded with building timber, which the Northmen exported thence to Greenland. It is natural, therefore, to conclude that also in Vinland itself they made use of this material in the construction of their dwelling houses, as is likewise confirmed by the Sagas, which expressly call the great houses (mikil hús) erected by Leif and Thortinn Karlsefne búðir, i. e. wooden houses [8]. Wood is a substance very subject to decay. The wooden buildings which were erected in Vinland in the 11th and 12th centuries must have long ago perished. After the 13th century it seems probable that the Northmen gradually intermixed with the Aborigines of the country, as was the case in a somewhat later period in Greenland. They accordingly more and more lost their original civilization, and as the connexion with the mother country in the subsequent centuries ceased to be upheld, they gradually degenerated into a state of savagism, no longer erecting such buildings, nor feeling any interest in -the maintenance of those, which they had inherited from their ancestors. It will accordingly be perceived that the circumstance of no remains of stone buildings being hitherto found in those regions affords no proof whatever against their having been in days of yore inhabited by a civilized European nation. Here, however, an opportunity presents itself of calling in question the correctness of the assertion, that in the Vinland of the Scandinavians no remains are to be found of stone buildings from the Ante-Columbian period. The ancient structure in Newport, respecting which Dr. Webb has given us the preceding account, merits a more attentive consideration.

There is no mistaking in this instance the style in which the more ancient stone edifices of the North were constructed, the style which belongs to the Roman or Ante-Gothic architecture, and which, especially after the time of Charlemagne, diffused itself from Italy over the whole of the West and North of Europe, where it continued to predominate until the close of the 12th century; that style which some authors have from one of its most striking characteristics called the round arch style, the same which in England is denominated Saxon and some times Norman architecture.

On the ancient structure in Newport there are no ornaments remaining, which might possibly have served to guide us in assigning the probable date of its erection. That no vestige whatever is found of the pointed arch, nor any approximation to it, is indicative of an earlier rather than of a later period. From such characteristics as remain, however, we can scarcely form any other inference than one, in which I am persuaded that all who are familiar with Old Northern architecture will concur, THAT THIS BUILDING WAS ERECTED AT A PERIOD DECIDEDLY NOT LATER THAN THE 12TH CENTURY. This remark applies, of course, to the original building only, and not to the alterations that it subsequently received; for there are several such alterations in the upper part of the building which cannot be mistaken, and which were most likely occasioned by its being adapted in modern times to various uses, for example as the substructure of a windmill, and latterly as a hay magazine. To the same times may be referred the windows, the fire place, and the apertures made above the columns. That this building could not have been erected for a windmill, is what an architect will easily discern.

The monopteral temples of ancient Greece form perhaps the prototype of such structures of which the early ecclesiastical architecture can doubtless furnish other specimens, particularly in the countries of the South [9]. As a building of this kind We may mention the church of Santa Maria della Pinta in Palermo, which had not close walls, but only ranges of pillars connected together by arches [10].

The history of art in the ancient countries of the North, more especially as regards architecture, has been as yet but very little explored. There remain, besides, very few structures of the 11th and 12th centuries in such a state as to enable us to trace the original style of building. But as these structures merit by means of delineations and descriptions to be rendered accessible to a greater number of investigators, the Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries intend, in their Annals of next year, to commence a series of communications on some of the more important architectural remains of the olden time of the North, for which purpose one of our ablest artistical historians [11] has promised his assistance. Referring to the more detailed descriptions to be given in the Annals, I shall at present confine myself to exhibiting, for the purpose of being compared with the ancient structure in Newport, three buildings in Denmark, belonging to the remote epoch in question.

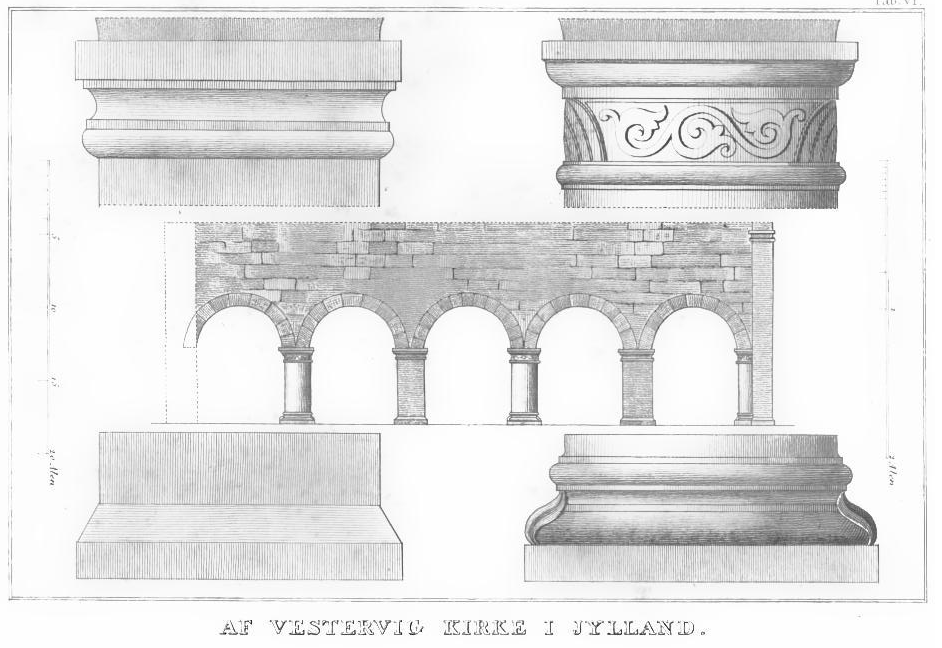

VESTERVIG CHURCH IN JUTLAND situated near the western inlet of Lümfiord. This church, Ecclesia Scti Theodgari, belonged originally to the Augustine Monastery of this place, and was founded about the year 1110 in honor of St. Thöger, St. Theodgarus, who lived in the 11th century, is said to have been born in Thüringen, went from thence first to England, from whence he repaired to Norway and was made chaplain to St. Olave, but came after the fall of that monarch to Denmark. The church was not finished till towards the end of the century (1197). This church is an oblong building: the side walls of its nave, whereof one is represented in Tab. VI, are constructed of blocks of hewn granite, and each of them is supported on five semicircular arches, the pillars of which are alternately round and square. The walls rest on the low shafted pillars alone, without being supported by buttresses. This edifice, which has so much in common with the ancient structure in Newport, and, like it, recommends itself to us by its architectural simplicity, has for its model the early style of the Christian Roman Basilica.

The earliest settlement in Vinland occurs in the 11th century, when wooden edifices were far more general than in the subsequent centuries [7]. The country abounded with building timber, which the Northmen exported thence to Greenland. It is natural, therefore, to conclude that also in Vinland itself they made use of this material in the construction of their dwelling houses, as is likewise confirmed by the Sagas, which expressly call the great houses (mikil hús) erected by Leif and Thortinn Karlsefne búðir, i. e. wooden houses [8]. Wood is a substance very subject to decay. The wooden buildings which were erected in Vinland in the 11th and 12th centuries must have long ago perished. After the 13th century it seems probable that the Northmen gradually intermixed with the Aborigines of the country, as was the case in a somewhat later period in Greenland. They accordingly more and more lost their original civilization, and as the connexion with the mother country in the subsequent centuries ceased to be upheld, they gradually degenerated into a state of savagism, no longer erecting such buildings, nor feeling any interest in -the maintenance of those, which they had inherited from their ancestors. It will accordingly be perceived that the circumstance of no remains of stone buildings being hitherto found in those regions affords no proof whatever against their having been in days of yore inhabited by a civilized European nation. Here, however, an opportunity presents itself of calling in question the correctness of the assertion, that in the Vinland of the Scandinavians no remains are to be found of stone buildings from the Ante-Columbian period. The ancient structure in Newport, respecting which Dr. Webb has given us the preceding account, merits a more attentive consideration.

There is no mistaking in this instance the style in which the more ancient stone edifices of the North were constructed, the style which belongs to the Roman or Ante-Gothic architecture, and which, especially after the time of Charlemagne, diffused itself from Italy over the whole of the West and North of Europe, where it continued to predominate until the close of the 12th century; that style which some authors have from one of its most striking characteristics called the round arch style, the same which in England is denominated Saxon and some times Norman architecture.

On the ancient structure in Newport there are no ornaments remaining, which might possibly have served to guide us in assigning the probable date of its erection. That no vestige whatever is found of the pointed arch, nor any approximation to it, is indicative of an earlier rather than of a later period. From such characteristics as remain, however, we can scarcely form any other inference than one, in which I am persuaded that all who are familiar with Old Northern architecture will concur, THAT THIS BUILDING WAS ERECTED AT A PERIOD DECIDEDLY NOT LATER THAN THE 12TH CENTURY. This remark applies, of course, to the original building only, and not to the alterations that it subsequently received; for there are several such alterations in the upper part of the building which cannot be mistaken, and which were most likely occasioned by its being adapted in modern times to various uses, for example as the substructure of a windmill, and latterly as a hay magazine. To the same times may be referred the windows, the fire place, and the apertures made above the columns. That this building could not have been erected for a windmill, is what an architect will easily discern.

The monopteral temples of ancient Greece form perhaps the prototype of such structures of which the early ecclesiastical architecture can doubtless furnish other specimens, particularly in the countries of the South [9]. As a building of this kind We may mention the church of Santa Maria della Pinta in Palermo, which had not close walls, but only ranges of pillars connected together by arches [10].

The history of art in the ancient countries of the North, more especially as regards architecture, has been as yet but very little explored. There remain, besides, very few structures of the 11th and 12th centuries in such a state as to enable us to trace the original style of building. But as these structures merit by means of delineations and descriptions to be rendered accessible to a greater number of investigators, the Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries intend, in their Annals of next year, to commence a series of communications on some of the more important architectural remains of the olden time of the North, for which purpose one of our ablest artistical historians [11] has promised his assistance. Referring to the more detailed descriptions to be given in the Annals, I shall at present confine myself to exhibiting, for the purpose of being compared with the ancient structure in Newport, three buildings in Denmark, belonging to the remote epoch in question.

VESTERVIG CHURCH IN JUTLAND situated near the western inlet of Lümfiord. This church, Ecclesia Scti Theodgari, belonged originally to the Augustine Monastery of this place, and was founded about the year 1110 in honor of St. Thöger, St. Theodgarus, who lived in the 11th century, is said to have been born in Thüringen, went from thence first to England, from whence he repaired to Norway and was made chaplain to St. Olave, but came after the fall of that monarch to Denmark. The church was not finished till towards the end of the century (1197). This church is an oblong building: the side walls of its nave, whereof one is represented in Tab. VI, are constructed of blocks of hewn granite, and each of them is supported on five semicircular arches, the pillars of which are alternately round and square. The walls rest on the low shafted pillars alone, without being supported by buttresses. This edifice, which has so much in common with the ancient structure in Newport, and, like it, recommends itself to us by its architectural simplicity, has for its model the early style of the Christian Roman Basilica.

What is also characteristical in the ancient structure at Newport, is the lo\v shafted columns which support the superstructure; they are of unusual thickness both in proportion to their distance from one another and to their height. The intervals between the pillars are equal to about 1 1/2 of their diameter, and the columns, including the base and capital, are little more than three diameters of the column in height.

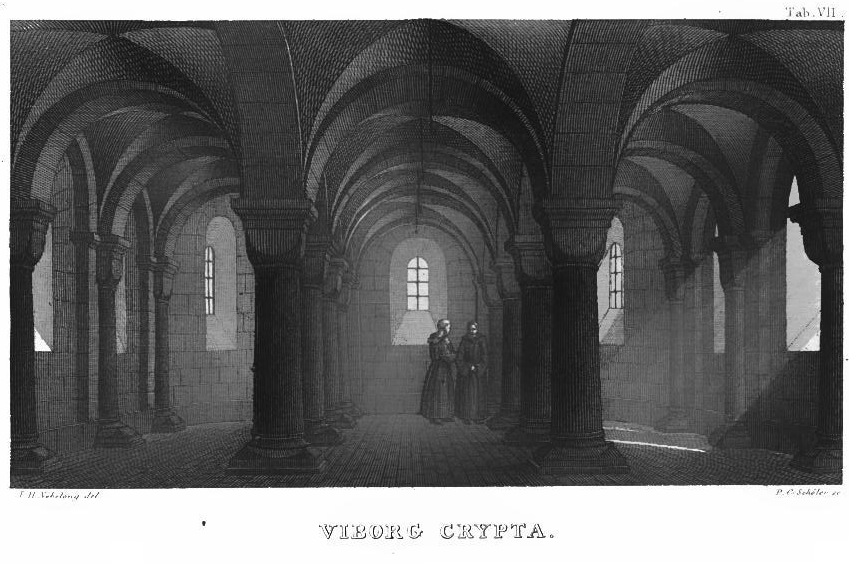

THE CRYPT AT VIBORG in Jutland (Tab. VII) under the Cathedral Church of that place, formerly called Есclesia Cathedralis beatæ Mariæ Virginis. This church is said to have been originally built in the 11th century during the reign of Canute the Great, or of his immediate successors; but, being found too small, it was during the reign of King Nicolas, about the year 1128, rebuilt from the foundation on a much larger scale. It was not, however, finished till about the year 1169. Meanwhile the Crypt may be referred to the commencement of the 12th century, like that under the Cathedral Church of Lund in Scania to which it bears so great a resemblance [12].

THE CRYPT AT VIBORG in Jutland (Tab. VII) under the Cathedral Church of that place, formerly called Есclesia Cathedralis beatæ Mariæ Virginis. This church is said to have been originally built in the 11th century during the reign of Canute the Great, or of his immediate successors; but, being found too small, it was during the reign of King Nicolas, about the year 1128, rebuilt from the foundation on a much larger scale. It was not, however, finished till about the year 1169. Meanwhile the Crypt may be referred to the commencement of the 12th century, like that under the Cathedral Church of Lund in Scania to which it bears so great a resemblance [12].

|

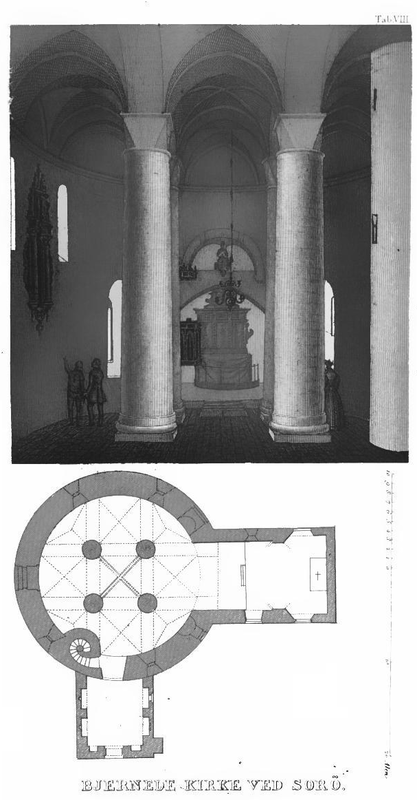

BIERNEDE CHURCH NEAR SORÖ in Seeland, first erected about the middle of the 12th century by Ebbe, a son of Skialm White and brother of Archbishop Absalon’s father Asker Ryg [13]; and it was rebuilt of stone by Ebbe’s son Sune, the hero celebrated in the Knytlinga Saga, who during the expedition against Rügen in 1168 was sent by King Waldemar the I to the castle of Arcona to break down the idol of Swantevit. Of this church, which is a round: building, the Society has had a drawing made for the purpose of inserting it here; Tab. VIII. It will subsequently appear in the Annals with a detailed description. In the round building, at equidistant intervals of 7 1/2 feet from each other, are four columns which, including their bases and capitals, are 24 feet in height. From these columns spring semicircular arches, which serve both to connect the columns with each other and also with the outer wall of the building. Here in Denmark there are still other round buildings to be met with from that early period. Of these I may mention Thorsager Church in Jutland, which from its description appears to resemble that at Biernede; and four in Bornholm, viz. St. Laurence’s, St. Nicolas’s, St. Olave’s, and All Saints’ or New Church. Of these St. Laurence’s or, as it is now called, Öster Lars Church may perhaps be the most deserving of our attention here, on account of an inner round building in the same; but respecting the construction of which I am for the present unable to give a detailed account for want of correct drawings [14].

“For what use was this Ante-Columbian building originally intended?” is a question naturally suggested by the first view of it, That the primary and principal object of its being erected was to serve as a watch tower, is what I cannot admit [15], although very possibly it may have been occasionally used as a station from whence to keep a look out over the adjacent sea. On the contrary I am more inclined to believe that it had a sacred destination, and that it belonged to some monastery or Christian place of worship of one of the chief parishes in Vinland. In GREENLAND there are still to be found ruins of several round buildings in the vicinity of the churches. One of this description, the diameter of which is about 26 feet, is situate at the distance of 300 feet to the eastward of the great church in Igalikko; another of 44 feet in diameter at the distance of 440 feet to the eastward of the church in Kakortok; this is constructed of rough stones of from 2 to 5 feet in height; a third of 32 feet in diameter among the ruins of 111 buildings at Kanikitsok or Iglorsoït in the firth of Sermelik. These lie on an area of about 600 feet in length, which is, as it were, sown with prostrate ruins, now so completely over grown that their original plan cannot with any certainty be discerned. The most discernible is the circular building in the southeastern corner of the area. Very close to it is a ruin about 20 feet long and 16 feet broad, respecting which it is difficult to say whether it was formerly connected with the other or not. These round buildings have been most likely Baptisteries; for it was the practice in elder times to erect separate buildings as Baptisteries, distinct from the churches near them [16], it being the received opinion that no one could enter the sacred edifice of the church, until he had first been initiated by the rite of baptism. As a separate Baptistery we may mention the Constantine Baptistery near the Lateran Basilica in Roule; and similar ones are also found in other of the considerable towns of Italy, for example, in Florence, Ravenna, Parma, Pisa [17] |

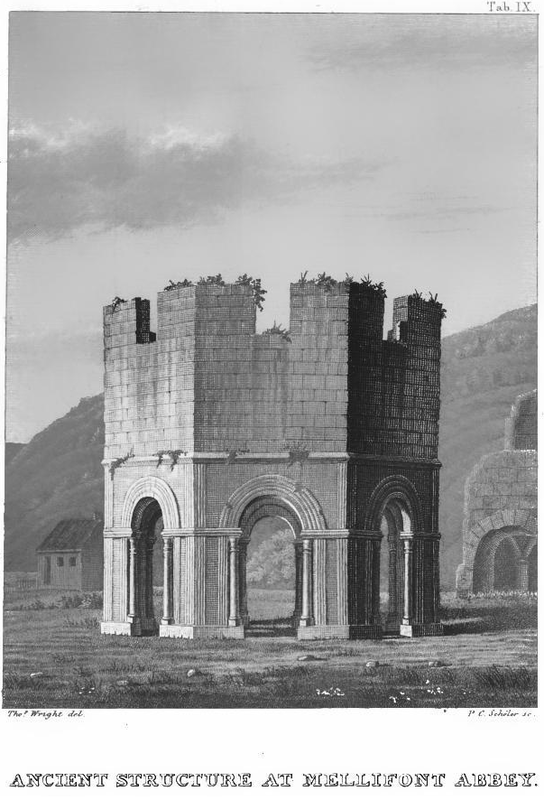

Among the ruins of MELLIFONT ABBEY in the county of Louth in Ireland, there is found, close to the Chapel of St. Bernard, an octagonal structure in the Roman style of the 12th century, probably coeval with the foundation of the Monastery [18] A. D. 1141. Of this structure there is a representation [19] given in Tab. IX. Each side is perforated by an arched doorway, and the exterior angles are formed by pilasters, on which the whole structure rests. The inhabitants of the neighbourhood call it a bath; but it seems more probable, and this is also the conjecture of the Irish Antiquarians, that it was а Baptistery. The ornaments were all of blue marble, both within and without, and when perfect it must have been master piece of its kind. A structure, on which so much pains had been bestowed, may doubtless seem to have been intended for a nobler destination than to serve as a bath.

The Ante-Columbian structure in Newport bears so much resemblance to this octagonal building [20] that it must appear probable, that it was intended for a similar Christian use‚ and has possibly belonged to a church, or a monastery founded in Vinland by the ancient Northmen.

The idea which I have formed from the scanty information of the 12th century respecting the relations with America the epoch in question, I shall now proceed to lay before my readers, leaving to a more fortunate futurity, which will doubtless he possessed of much additional light, to clear up, correct, or confirm the views, which, guided merely by the feeble glimpses of the present moment I have been able to discern.

At the commencement of the century in question the population of Greenland had considerably increased, churches had been built in many of the firths both in the eastern and western settlement, or Bygð. Colonies had been settled in Vinland, to which country many were allured by the superior mildness of the climate and more abundant supply of the means of subsistence. The same was probably also the ease with respect to Markland. The feeling of independence in the hold and freeminded people, the insulated situation of the settlements in so many firths, many of them widely separated from each other, and where navigation during a great part of the year was so hazardous, the difficulty or rather the impossibility of any of the Bishops of Iceland exercising an inspection over the ecclesiastical affairs of the people — all these united circumstances awakened in the inhabitants of Greenland the desire of having a Bishop of their own. They probably under these circumstances applied to Gissur Isleifson, formerly Bishop of all Iceland, but then only Bishop of Skalholt; for in 1106 a separate Bishopric had been erected at Holum. Most likely in consequence of mutual consultation with Sæmund Frode at Odde [21], with Thorlak Runolfson and other confidential. friends of Gissur, ERIC GNUPSON was selected for discharging in the mean time the functions of a Bishop in Greenland — а man of distinguished lineage, descended through the Christian settler (landnámsmann) Örlyg of Esiuherg from the ancient Hersers of Sogn in Norway, and through the district governor (goði) Grimkel of Blaskogum from Biorn Gullhere at Gullberastad, who at the first occupation of Iceland took possession of the southern part of Reykiardal [22]. After having this charge committed to him, but without as yet being regularly appointed or consecrated by the Pope or Archbishop, Eric accordingly repaired to Greenland [23] in 1112 or 1113. There under the name of Bishop [24] he superintended the church for several years; and accounts having arrived from Vinland of the distressed state of the church in that colony situate so remote from the mother country, he was induced to make a voyage thither with a view of confirming in their faith such of the settlers as were Christian, and of converting to Christianity such as still remained heathen. He subsequently returned to Iceland, probably in the year 1120. Thorlak Runolfson was then Bishop of Skalholt, having been elevated to that chair two years previously. To this worthy prelate, his equal in age and possibly his former fellow student, he accordingly adressed himself, — to the grandson of Snorre Thorfinson, who was born in America in the year 1008, who himself preserved and doubtless committed to writing the valuable accounts which we have of the voyage of his great-grandfather Thorfinn Karlsefne, and of Gudrid to America. Confirmed by his advice in his resolution of repairing to Vinland, and furnished by him with a letter of recommendation, he then went to Denmark, and in the beginning of the year 1121 he was consecrated to his sacred office by Archbishop Adzer in Lund [25]. He then either went immediately from Denmark to Vinland, or, what seems more probable, he in the spring returned to Iceland in order during the same summer to repair to his new destination accompanied by several clergymen and new colonists. As consecrated Bishop of Greenland, he would begin his functions by taking under his protection the ecclesiastical affairs of the colony which had emanated from thence, and his first intention was doubtless to return to Greenland as soon as he got these affairs brought into a secure train. But after having arrived at Vinland he came to the resolution of fixing his residence there.

Accounts of Bishop Eric's arrival in Vinland, and of his abdication of the bishopric of Gardar might as early as 1122 have reached Greenland. Greenland was thus .again without a Bishop. One of that country’s most distinguished men at that time was Sokke Thorerson, who, like Eric the Red (from whom he was most probably descended) resided at Brattalid in Ericsfiord. In 1123 this man caused the people to be convened to a general public meeting, where he made known to them whis advice and his wish that the country should be no longer without a Bishop [26], but that a permanent bishopric should be erected. On this being agreed to, he desired his son Einar to proceed on this errand to Norway, where at that time Sigurd, surnamed Jorsalafare, was King. To him Einar repaired, and requested his assistance; whereupon the King persuaded an able clerk of the name of Arnald to undertake this onerous charge, and sent him to Denmark, where in the year 1124 he was consecrated by Archbishop Adzer in Lund. In company with Einar Arnald then first went back to Norway, and from thence repaired in 1125 to Iceland, where he spent the following winter at Odde as the guest of Sæmund Frode, who, on hearing of his arrival at Holtavatsos, had repaired thither to invite him to his house. Having in 1126 attended the general public meeting in Iceland, he in the same year went with Einar to Greenland, where he took up his residence at Gardar [27] as Bishop. From that time Greenland had permanent Bishops.

In different expressions, so that we cannot suppose the one to have copied from the other, the best annal codices make mention of Bishop Eric’s voyage to Vinland [28]. But about his proceedings in Vinland such ancient records as we have in our possession make no mention. We must therefore leave to future investigations and researches, whether a more clear light may be discerned in this obscure part of the Ante-Columbian history of America. Haply they may lead to a more certain decision as to whether the ancient Tholus in Newport [29], of which the erection appears to be coeval with the time of Bishop Eric, did really belong to a Scandinavian church or monastery, where in alternation with Latin masses the old Danish tongue was heard seven hundred years ago.

The idea which I have formed from the scanty information of the 12th century respecting the relations with America the epoch in question, I shall now proceed to lay before my readers, leaving to a more fortunate futurity, which will doubtless he possessed of much additional light, to clear up, correct, or confirm the views, which, guided merely by the feeble glimpses of the present moment I have been able to discern.

At the commencement of the century in question the population of Greenland had considerably increased, churches had been built in many of the firths both in the eastern and western settlement, or Bygð. Colonies had been settled in Vinland, to which country many were allured by the superior mildness of the climate and more abundant supply of the means of subsistence. The same was probably also the ease with respect to Markland. The feeling of independence in the hold and freeminded people, the insulated situation of the settlements in so many firths, many of them widely separated from each other, and where navigation during a great part of the year was so hazardous, the difficulty or rather the impossibility of any of the Bishops of Iceland exercising an inspection over the ecclesiastical affairs of the people — all these united circumstances awakened in the inhabitants of Greenland the desire of having a Bishop of their own. They probably under these circumstances applied to Gissur Isleifson, formerly Bishop of all Iceland, but then only Bishop of Skalholt; for in 1106 a separate Bishopric had been erected at Holum. Most likely in consequence of mutual consultation with Sæmund Frode at Odde [21], with Thorlak Runolfson and other confidential. friends of Gissur, ERIC GNUPSON was selected for discharging in the mean time the functions of a Bishop in Greenland — а man of distinguished lineage, descended through the Christian settler (landnámsmann) Örlyg of Esiuherg from the ancient Hersers of Sogn in Norway, and through the district governor (goði) Grimkel of Blaskogum from Biorn Gullhere at Gullberastad, who at the first occupation of Iceland took possession of the southern part of Reykiardal [22]. After having this charge committed to him, but without as yet being regularly appointed or consecrated by the Pope or Archbishop, Eric accordingly repaired to Greenland [23] in 1112 or 1113. There under the name of Bishop [24] he superintended the church for several years; and accounts having arrived from Vinland of the distressed state of the church in that colony situate so remote from the mother country, he was induced to make a voyage thither with a view of confirming in their faith such of the settlers as were Christian, and of converting to Christianity such as still remained heathen. He subsequently returned to Iceland, probably in the year 1120. Thorlak Runolfson was then Bishop of Skalholt, having been elevated to that chair two years previously. To this worthy prelate, his equal in age and possibly his former fellow student, he accordingly adressed himself, — to the grandson of Snorre Thorfinson, who was born in America in the year 1008, who himself preserved and doubtless committed to writing the valuable accounts which we have of the voyage of his great-grandfather Thorfinn Karlsefne, and of Gudrid to America. Confirmed by his advice in his resolution of repairing to Vinland, and furnished by him with a letter of recommendation, he then went to Denmark, and in the beginning of the year 1121 he was consecrated to his sacred office by Archbishop Adzer in Lund [25]. He then either went immediately from Denmark to Vinland, or, what seems more probable, he in the spring returned to Iceland in order during the same summer to repair to his new destination accompanied by several clergymen and new colonists. As consecrated Bishop of Greenland, he would begin his functions by taking under his protection the ecclesiastical affairs of the colony which had emanated from thence, and his first intention was doubtless to return to Greenland as soon as he got these affairs brought into a secure train. But after having arrived at Vinland he came to the resolution of fixing his residence there.

Accounts of Bishop Eric's arrival in Vinland, and of his abdication of the bishopric of Gardar might as early as 1122 have reached Greenland. Greenland was thus .again without a Bishop. One of that country’s most distinguished men at that time was Sokke Thorerson, who, like Eric the Red (from whom he was most probably descended) resided at Brattalid in Ericsfiord. In 1123 this man caused the people to be convened to a general public meeting, where he made known to them whis advice and his wish that the country should be no longer without a Bishop [26], but that a permanent bishopric should be erected. On this being agreed to, he desired his son Einar to proceed on this errand to Norway, where at that time Sigurd, surnamed Jorsalafare, was King. To him Einar repaired, and requested his assistance; whereupon the King persuaded an able clerk of the name of Arnald to undertake this onerous charge, and sent him to Denmark, where in the year 1124 he was consecrated by Archbishop Adzer in Lund. In company with Einar Arnald then first went back to Norway, and from thence repaired in 1125 to Iceland, where he spent the following winter at Odde as the guest of Sæmund Frode, who, on hearing of his arrival at Holtavatsos, had repaired thither to invite him to his house. Having in 1126 attended the general public meeting in Iceland, he in the same year went with Einar to Greenland, where he took up his residence at Gardar [27] as Bishop. From that time Greenland had permanent Bishops.

In different expressions, so that we cannot suppose the one to have copied from the other, the best annal codices make mention of Bishop Eric’s voyage to Vinland [28]. But about his proceedings in Vinland such ancient records as we have in our possession make no mention. We must therefore leave to future investigations and researches, whether a more clear light may be discerned in this obscure part of the Ante-Columbian history of America. Haply they may lead to a more certain decision as to whether the ancient Tholus in Newport [29], of which the erection appears to be coeval with the time of Bishop Eric, did really belong to a Scandinavian church or monastery, where in alternation with Latin masses the old Danish tongue was heard seven hundred years ago.

Notes

[1] To preserve the ruin from mischievous injury a fence has in later times been constructed around it; but this as being modern is omitted in the engraving.

[2] This drawing forms the ground work of the accompanying steel engraving (Tab. III). It is to be remarked however that the ruin is in many places still more dilapidated than appears in the delineation, which was sent to us in the form of an outline without being tilled up.

[3] See Ant. Amer. p. 273, 275, 276, 294.

[4] Ant. Am. p. 36, 40, 58, 67, 118.

[5] Ant. Am. p. 264-65, cf. p. 453.

[6] Ant. Am. p. 315.

[7] Of this and the succeeding century are the wooden churches delineated and described in J. C. C. Dahl’s admirable work, “Denkmale einer schr ausgebildeten Holzbeukunst aus den frühesten Jahrhunderten in den innern Landschaften Norwegens, Dresden 1837”.

[8] Ant. Am. 32, 40, 57, 66, 155.

[9] That a similar style of architecture was also known very early in the countries of the North is what we may infer from the accounts given in the elder Edda (Grimnismál l5, 23, 24) of the ideas, which the ancient Scandinavians entertained of the abodes of the gods, particularly of Thor’s hall Bilskírnir. Agreeably to these accounts we must suppose that such a temple was supported by pillars (studdr), which were connected together by rounded arches (með bugum), the intermediate spaces forming many gate ways (dуr). It is however difficult to form any positive opinion on this subject; for at the introduction of Christianity into our northern countries all the pagan temples were entirely destroyed.

[10] The length of the nave was about 30 paces, and its breadth about 7 1/2 paces. It was one of the finest churches which the Greeks built in Sicily. According to Simon of Leontino, who was Bishop of Syracuse in the 13th century, it is said to have been erected by Belisarius in gratitude for a. victory which he obtained over the Goths in 535. The account of this remarkable building, which was recommended to my attention by Professor Höyen, is to be found in Invige’s Palermo Sacro, Parte II p. 424, according to a MS of 1581. Its northern facade fronted the main street of Palermo, called Cassaro: having sustained injury in consequence of the formation of this street in 1564, it was in the year 1618 entirely pulled down.

[11] Professor Höyen to whom I am also indebted for the following account of Vestervig Church, which he inspected some years ago.

[12] See C. G. Brunius’s meritorious work “Nordens äldsta Metropolitankyrka eller historiek och architectonisk Beskrifning öfver Lunds Domkyrka. Lund 1836.

[13] By this family were erected several other buildings, some of which are still extant, such as the Conventual church of the Bernardines in Sorö, the churches of Fienncslöv and at Calundborg.

[14] ISome of the round churches in Great Britain are deserving of mention here, such as, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Cambridge built about 1122; see Archæologia Vol. Vl p. 173.

[15] Any such watch tower must have been defended by a rampart raised round about it (vígi or virki) consisting of an earthen mound or of several rows of pallisades, the intermediate space between which was filled up with stones, clods, or liveturf; but of such we find no trace. A skiðgarðr, or wooden paling, would scarcely have sufficed, although Thorfinn Karlsefne in the year 1008, when he apprehended an attack of the Skrælings (Esquimaux), contented himself with raising such a fence about his house in Vinland (læír gera skiðgarð ramligan um bæ sinn, ok bjuggust um).

[16] See Eusebius Lib. X hist. eccles. cap. IV.

[17] The Baptistery belonging to the Basilica in Pisa, which was built between the years 1152 and 1160 by the architect Deotisalvi, deserves to be mentioned here as а round building of about the same epoch, but on which however a much greater degree of magnificence has been bestowed; See Theatrum Basilicæ Pisanæ, cura et studio Josephi Martini, Romæ 1728.

[18] See Cisterciensium Annalium autore Angelo` Manrique T. I, p. 403-404.

[19] From Louthiana, or an Introduction to the Antiquities of Ireland by Thomas Wright, London 1758. From a publication received several years ago from the learned Irish Antiquary George Petrie, the following account of this monastery is extracted: “The Abbey of Mellifont was originally one of the most important and magnificent monastic edifices ever erected in Ireland. It was founded, or endowed, by Donough M‘Corvoill, or O’Carriol, prince of Oirgiallach, the present Oriel, А. D. 1141, at the solicitation of St. Malachy, the pious and learned Archbishop of Armagh, and was the first Cistercian Abbey erected in Ireland. The monks by whom it was first inhabited were sent over from the parent Monastery of Clairvaux in Champagne, by St. Bernard, and four of them were Irishmen, who had been educated there for the purpose. On the occasion of the consecration of the Church of Mellifont in 1157, a remarkable Synod was held here, which was attended by the primate Gelasius, Christian Bishop of Lismore and apostolic legate, seventeen other bishops, and innumerable clergymen of inferior ranks. There were present also Murchertach, or Murtogh O’Loghlin, King of Ireland, O’Eochadha, prince of Ulidia, Tiernan O’Ruaire, prince of Breiffny, and O’Kerbhaill, or O’Carroll, prince of Ergall, or Oriel. Of this important monastic foundation but trifling remains are low to he found, but these are sufficient evidence of its ancient beauty and splendor. They consist of the ruins of a beautiful little chapel, dedicated to Saint Bernard, which in its perfect state was an exquisite specimen of the Gothic, or pointed architecture of the thirteenth century. This chapel is partly imbedded in the rock, the floor being considerably lower than the outer surface, and consists of а crypt and an upper apartment. Besides this, there is the octagonal building, the style of which indicates an earlier age; and the lofty abbey gateway.

[20] In Scandinavia at the introduction of' the Reformation the Monasteries were abolished, und almost every trace of them in their original state is lost. We have it not in our power, therefore, to shew any similar building. If we may judge from some hewn stones, which originally formed part of one of’ the buildings belonging to the Monastery of Vestervig in Jutland, but now pulled down, the said building must have been of an octagonal shape, probably a Baptistery, like that at Mellifout Abbey, detached from the Monastery. The stones in question have since been made use of to enclose a well; and in order to employ them without rehewing them, it has been necessary to give the enclosure an octagonal form.

[21] The advice of Sæmund Sigfusson was asked and followed on many important occasions. This learned priest had in his younger years visited Germany and France with the view of there prosecuting his studies. For several years he frequented the school at Paris, where he would have remained, had it not been for his relation Jon Ögmundson, afterwards Bishop of llolum, who also travelled in France and who persuaded him to return to his native country. After his return in 1076 he fixed his residence at his paternal estate Odde in the southern quarter of Iceland. There he opened a school, which Eric Gnupson, whose family resided in that neighbourhood, most likely attended.

[22] Landnáma 1, 13, 19; collate the Genealogical Table VI in Ant. Amer.

[23] All that as stated on this subject in the Flatey-Annals under A. D. 1113, and in Lügmanns Annals under A. D. 1112, is “Ferð Eríks biskups, Bishop Eric’s voyage”. As both these annals make mention under A. D. 1121 of Bishop Eric’s voyage to Vinland, it is probable that they here allude to his voyage to Greenland.

[24] He is styled “Bishop” not only in the Annals but also in the Landnáma, where he is called Grælendinga biskup. Rimbegla, p. 321 gives the List of Bishops of Gardar in Greenland, thus: þessir hafa biskupar verit á Grænlandi í Görðum: Eirekr, Haraldr (Arnaldr), Jón knútr (knari), Jón smirill, Helgi Nicolás, Ólafr, Bokki, Árni, Álfr.

[25] The Oddo-Annals, whereof the first part is ascribed to Bishop Eric’s contemporary, the celebrated historian and antiquarian, Sæmund, surnamed Frode, i. e. the Learned, and who resided et Odde, have under A. D. 1121 “Vgðr Eiríkr Grænlendinga biskup fyrrsir, Eric consecrated, first Bishop of the Greenlanders.” It is not mentioned, to be sure, where this consecration took place, but the contemporary Bishops of Iceland are expressly said to have been consecrated by Archbishop Adzer in Lund in Denmark, whose Archbishopric extended over the whole of the North; thus Jon Ögmundson of Holum in 1106, Thorlak Runolfson of Skalholt in 1118, Ketil Thorsteinson of Holum in 1122, and Magnus Einarson of Skalholt in 1134. It may accordingly, I presume, be considered indubitable that Bishop Eric was also consecrated in Lund.

[26] at landit væri eigi lengr biskupslaust, see the detailed account of this in the chronicle of Einar Sokkason in Grönlands historiske Mindesmærker II p. 669-742.

[27] Biskup setti stól sinn í Görðum, ok rèðst þángat til.

[28] See Ant. Amer. p. 261-262.

[29] This ancient building certainly merits a still more accurate investigation, and excavations ought to be made in the immediate vicinity of the same.

[2] This drawing forms the ground work of the accompanying steel engraving (Tab. III). It is to be remarked however that the ruin is in many places still more dilapidated than appears in the delineation, which was sent to us in the form of an outline without being tilled up.

[3] See Ant. Amer. p. 273, 275, 276, 294.

[4] Ant. Am. p. 36, 40, 58, 67, 118.

[5] Ant. Am. p. 264-65, cf. p. 453.

[6] Ant. Am. p. 315.

[7] Of this and the succeeding century are the wooden churches delineated and described in J. C. C. Dahl’s admirable work, “Denkmale einer schr ausgebildeten Holzbeukunst aus den frühesten Jahrhunderten in den innern Landschaften Norwegens, Dresden 1837”.

[8] Ant. Am. 32, 40, 57, 66, 155.

[9] That a similar style of architecture was also known very early in the countries of the North is what we may infer from the accounts given in the elder Edda (Grimnismál l5, 23, 24) of the ideas, which the ancient Scandinavians entertained of the abodes of the gods, particularly of Thor’s hall Bilskírnir. Agreeably to these accounts we must suppose that such a temple was supported by pillars (studdr), which were connected together by rounded arches (með bugum), the intermediate spaces forming many gate ways (dуr). It is however difficult to form any positive opinion on this subject; for at the introduction of Christianity into our northern countries all the pagan temples were entirely destroyed.

[10] The length of the nave was about 30 paces, and its breadth about 7 1/2 paces. It was one of the finest churches which the Greeks built in Sicily. According to Simon of Leontino, who was Bishop of Syracuse in the 13th century, it is said to have been erected by Belisarius in gratitude for a. victory which he obtained over the Goths in 535. The account of this remarkable building, which was recommended to my attention by Professor Höyen, is to be found in Invige’s Palermo Sacro, Parte II p. 424, according to a MS of 1581. Its northern facade fronted the main street of Palermo, called Cassaro: having sustained injury in consequence of the formation of this street in 1564, it was in the year 1618 entirely pulled down.

[11] Professor Höyen to whom I am also indebted for the following account of Vestervig Church, which he inspected some years ago.

[12] See C. G. Brunius’s meritorious work “Nordens äldsta Metropolitankyrka eller historiek och architectonisk Beskrifning öfver Lunds Domkyrka. Lund 1836.

[13] By this family were erected several other buildings, some of which are still extant, such as the Conventual church of the Bernardines in Sorö, the churches of Fienncslöv and at Calundborg.

[14] ISome of the round churches in Great Britain are deserving of mention here, such as, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Cambridge built about 1122; see Archæologia Vol. Vl p. 173.

[15] Any such watch tower must have been defended by a rampart raised round about it (vígi or virki) consisting of an earthen mound or of several rows of pallisades, the intermediate space between which was filled up with stones, clods, or liveturf; but of such we find no trace. A skiðgarðr, or wooden paling, would scarcely have sufficed, although Thorfinn Karlsefne in the year 1008, when he apprehended an attack of the Skrælings (Esquimaux), contented himself with raising such a fence about his house in Vinland (læír gera skiðgarð ramligan um bæ sinn, ok bjuggust um).

[16] See Eusebius Lib. X hist. eccles. cap. IV.

[17] The Baptistery belonging to the Basilica in Pisa, which was built between the years 1152 and 1160 by the architect Deotisalvi, deserves to be mentioned here as а round building of about the same epoch, but on which however a much greater degree of magnificence has been bestowed; See Theatrum Basilicæ Pisanæ, cura et studio Josephi Martini, Romæ 1728.

[18] See Cisterciensium Annalium autore Angelo` Manrique T. I, p. 403-404.

[19] From Louthiana, or an Introduction to the Antiquities of Ireland by Thomas Wright, London 1758. From a publication received several years ago from the learned Irish Antiquary George Petrie, the following account of this monastery is extracted: “The Abbey of Mellifont was originally one of the most important and magnificent monastic edifices ever erected in Ireland. It was founded, or endowed, by Donough M‘Corvoill, or O’Carriol, prince of Oirgiallach, the present Oriel, А. D. 1141, at the solicitation of St. Malachy, the pious and learned Archbishop of Armagh, and was the first Cistercian Abbey erected in Ireland. The monks by whom it was first inhabited were sent over from the parent Monastery of Clairvaux in Champagne, by St. Bernard, and four of them were Irishmen, who had been educated there for the purpose. On the occasion of the consecration of the Church of Mellifont in 1157, a remarkable Synod was held here, which was attended by the primate Gelasius, Christian Bishop of Lismore and apostolic legate, seventeen other bishops, and innumerable clergymen of inferior ranks. There were present also Murchertach, or Murtogh O’Loghlin, King of Ireland, O’Eochadha, prince of Ulidia, Tiernan O’Ruaire, prince of Breiffny, and O’Kerbhaill, or O’Carroll, prince of Ergall, or Oriel. Of this important monastic foundation but trifling remains are low to he found, but these are sufficient evidence of its ancient beauty and splendor. They consist of the ruins of a beautiful little chapel, dedicated to Saint Bernard, which in its perfect state was an exquisite specimen of the Gothic, or pointed architecture of the thirteenth century. This chapel is partly imbedded in the rock, the floor being considerably lower than the outer surface, and consists of а crypt and an upper apartment. Besides this, there is the octagonal building, the style of which indicates an earlier age; and the lofty abbey gateway.

[20] In Scandinavia at the introduction of' the Reformation the Monasteries were abolished, und almost every trace of them in their original state is lost. We have it not in our power, therefore, to shew any similar building. If we may judge from some hewn stones, which originally formed part of one of’ the buildings belonging to the Monastery of Vestervig in Jutland, but now pulled down, the said building must have been of an octagonal shape, probably a Baptistery, like that at Mellifout Abbey, detached from the Monastery. The stones in question have since been made use of to enclose a well; and in order to employ them without rehewing them, it has been necessary to give the enclosure an octagonal form.