John Warre Tyndale

The Island of Sardinia

1849

|

NOTE |

In 1843 Oxford-educated barrister John Warre Tyndale (1811-1897) traveled to Italy for reasons of health, in those wonderful days when the wealthy might decamp to a foreign locale for months or years of vacation time. In his travels, his friends impressed upon him the benefits of a jaunt to Sardinia, which he undertook and, after a long delay, described in a volume of observations published in 1849. His chapter on the mysterious megalithic towers called the Nuraghe and the stone tombs known as the sepulchers of giants remained for many years the longest and most detailed available in English. Belief in giants, and that the stone ruins of Bronze Age Sardinia belong to them, remains current on the island today.

|

CHAPTER II.

The Noraghe and the Sepolture de is Gigantes. --

Description and Enquiry into their Origin.

|

Chaos of ruins! who shall trace the void,

O’er the dim fragments cast a lunar light, And say, ‘here was or is,’ where all is douhly night? Childe Harold, Canto iv. 80.

|

As we shall shortly find some Noraghe in our route, it were well to arrest our steps to enquire a little about them. The ancient architectural remains known by the name Noraghe or Nurhag, are the most interesting objects in the island, and the unfathomable mysteries of their origin and purpose having hitherto baffled the learning and ingenuity of historians, archaeologists, and antiquaries, the following observations are merely offered as an analysis of La Marmora’s researches, of information obtained from other sources, as the result of a personal examination of these monuments, and a vague supposition of their origin.

The spelling of the name varies according to different authors, as much as the pronunciation, in the districts where they are found; consequently, Nur-hag, Nuraghe, Noraghe, Nurache, Nuraxi, and Our-ag, Or-ag, omitting the first letter n, are used indiscriminately; but, though Nur-hag may be perhaps more classically correct, Noraghe seems to be most generally adopted, and is of the masculine gender without a difference of termination in the plural.

All are built on natural or artificial mounds, whether in valleys, plains, or on mountains, and some are partially enclosed, at a slight distance, by a low wall of a similar construction to the building.

Their essential architectural feature is a truncated cone or tower, averaging from thirty to sixty feet in height, and from 100 to 300 in circumference at the base. The majority have no basement, but the rest are raised on one extending either in a corresponding or an irregular shape, and of which the perimeter varies from 300 to 653 feet, the largest yet measured.

The inward inclination of the exterior wall of the principal tower, which almost always is the centre of the building, is so well executed as to present in its elevation a perfect and continuously symmetrical line; but sometimes a small portion of the external face of the outer works of the basements, which are not regular, is straight and perpendicular; such instances are, however, very rare.

There is every reason to believe, though without positive proof, for none of the Noraghe are quite perfect, that the cone was originally truncated and formed thereby a platform on its summit.

The material of which they are built being always the natural stone of the locality, we accordingly find them of granite, limestone, basalt, trachitic porphyry, lava, and tufo; the blocks varying in shape and size from three to nine cubic feet, while those forming the architraves of the passages are sometimes twelve feet long, five feet wide, and the same in depth.

The surfaces present that slight irregularity which proves the blocks to have been rudely worked by the hammer, but with sufficient exactness to form regular horizontal layers; with few exceptions the stones are not polygonal, but when so, are without that regularity of form which would indicate the use of the rule; nor is their construction of the Cyclopean and Pelasgic styles; neither have they sculpture, ornamental work, or cement.

The external entrance, invariably between the E.S.E. and S. by W., but generally to the East of South, seldom exceeds five feet high and two feet wide, and is often so small as to necessitate crawling on all fours. The architrave, as previously mentioned, is very large; but, having once passed it, a passage varying from three to six feet high, and two to four wide, leads to the principal domed chamber, the entrance to which is sometimes by another low aperture as small as the first.

The spelling of the name varies according to different authors, as much as the pronunciation, in the districts where they are found; consequently, Nur-hag, Nuraghe, Noraghe, Nurache, Nuraxi, and Our-ag, Or-ag, omitting the first letter n, are used indiscriminately; but, though Nur-hag may be perhaps more classically correct, Noraghe seems to be most generally adopted, and is of the masculine gender without a difference of termination in the plural.

All are built on natural or artificial mounds, whether in valleys, plains, or on mountains, and some are partially enclosed, at a slight distance, by a low wall of a similar construction to the building.

Their essential architectural feature is a truncated cone or tower, averaging from thirty to sixty feet in height, and from 100 to 300 in circumference at the base. The majority have no basement, but the rest are raised on one extending either in a corresponding or an irregular shape, and of which the perimeter varies from 300 to 653 feet, the largest yet measured.

The inward inclination of the exterior wall of the principal tower, which almost always is the centre of the building, is so well executed as to present in its elevation a perfect and continuously symmetrical line; but sometimes a small portion of the external face of the outer works of the basements, which are not regular, is straight and perpendicular; such instances are, however, very rare.

There is every reason to believe, though without positive proof, for none of the Noraghe are quite perfect, that the cone was originally truncated and formed thereby a platform on its summit.

The material of which they are built being always the natural stone of the locality, we accordingly find them of granite, limestone, basalt, trachitic porphyry, lava, and tufo; the blocks varying in shape and size from three to nine cubic feet, while those forming the architraves of the passages are sometimes twelve feet long, five feet wide, and the same in depth.

The surfaces present that slight irregularity which proves the blocks to have been rudely worked by the hammer, but with sufficient exactness to form regular horizontal layers; with few exceptions the stones are not polygonal, but when so, are without that regularity of form which would indicate the use of the rule; nor is their construction of the Cyclopean and Pelasgic styles; neither have they sculpture, ornamental work, or cement.

The external entrance, invariably between the E.S.E. and S. by W., but generally to the East of South, seldom exceeds five feet high and two feet wide, and is often so small as to necessitate crawling on all fours. The architrave, as previously mentioned, is very large; but, having once passed it, a passage varying from three to six feet high, and two to four wide, leads to the principal domed chamber, the entrance to which is sometimes by another low aperture as small as the first.

The interior of the cone consists of one, two, or three domed chambers, placed one above the other and diminishing in size in proportion to the external inclination; the lowest averaging from fifteen to twenty feet in diameter, and from twenty to twenty-five in height. The base of each is almost always circular, but, when otherwise, elliptical; the edges of the stones, where the tiers overlay each other, are worked off, so that the interior assumes a semiovoidal form, or that of which the section would be a parabola; the apex being crowned with a large flat stone resting on the last circular layer, which is reduced to a small diameter. It has been said that in some Noraghe a metal ring is suspended from the apex; but the fact has yet to be proved; and this current belief of the peasants is, as a Sarde author has observed, like that entertained by them as to the existence of spirits in these buildings, “che come gli spettri, si veggono, e non si lascian toccare,” — “one sees them, but they do not let themselves be touched.”

In the interior of the lowest chamber and on a level with the floor, are frequently from two to four cells or niches, formed in the thickness of the masonry without external communication, varying from three to six feet long, two to four wide, and two to five high, and only accessible by very small entrances.

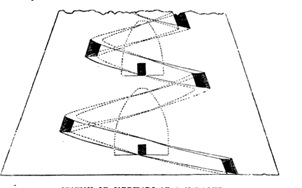

The access to the second and third chambers, as well as to the platform on the top of these Noraghe which have only one chamber, is by a spiral corridor made in the building either as a simple ramp with a gradual ascent, or with rough irregular steps made in the stones.

The corridor varies from three to six feet in height, and from two to four in width, and the outer side either inclines according to the external wall of the cone, and the inner side according to the domed chamber, or resembles in the section a segment of a circle.

The entrance to this spiral corridor is generally in the horizontal passage which leads from the external entrance to the first floor chamber of the cone; though sometimes it is by a small aperture in the chamber, about six or eight feet from the base, and very difficult of entry.

In the interior of the lowest chamber and on a level with the floor, are frequently from two to four cells or niches, formed in the thickness of the masonry without external communication, varying from three to six feet long, two to four wide, and two to five high, and only accessible by very small entrances.

The access to the second and third chambers, as well as to the platform on the top of these Noraghe which have only one chamber, is by a spiral corridor made in the building either as a simple ramp with a gradual ascent, or with rough irregular steps made in the stones.

The corridor varies from three to six feet in height, and from two to four in width, and the outer side either inclines according to the external wall of the cone, and the inner side according to the domed chamber, or resembles in the section a segment of a circle.

The entrance to this spiral corridor is generally in the horizontal passage which leads from the external entrance to the first floor chamber of the cone; though sometimes it is by a small aperture in the chamber, about six or eight feet from the base, and very difficult of entry.

The upper chambers are entered by a small passage at right angles to this corridor, and, opposite to this passage, is often a small aperture in the outer wall, having apparently no regular position, though frequently over the external entrance to the ground floor; while, in some instances, there are several apertures, so made that only the sky or most distant objects in the horizon are visible.

The Padre Angius has subdivided the Noraghe into four categories—the simple cones, the compound, the united, and those having outworks. These subdivisions would, however, be insufficient; for, though in their general characteristics the buildings have the closest affinity to each other, the minor points of difference are so varied and numerous, and the dilapidations have so altered their form and appearance, that any classification might not only be confusing but possibly erroneous.

Though there are upwards of 3000 now in existence, more or less in ruins, it may be fairly assumed that they were formerly more numerous, for though there is not the slightest ground for supposing that any have been built during the last 2500 years, there is evidence to prove that their destruction has been gradual and progressive. Forming a valuable quarry for the people in making their houses, chiudende or enclosures, and roads, every day’s spoliation so alters their appearance, that future travellers may not recognise those described by their predecessors; and another difficulty arises in the variety of names given to the same Noraghe, so that the information from the peasants is constantly though unintentionally incorrect, and productive of incessant mistakes. In general, they are called after some saint or personage, peculiar feature in the building, or proximity to a well known object, such as San Gavinu, ederosu, de tres bias, &c.

La Marmora has given details and admirable plans of several of the principal Noraghe, some of which will be mentioned in the following pages, together with those remarkable for any peculiar feature, selected from upwards of fifty that I measured.

The consideration of their origin and purpose may be prefaced by the abridged opinions of the authors who have hitherto entered upon the subject.

Stephanini believes them to have been trophies of victory; Vidal, the houses of the giants; Madao, the tombs of the antediluvians; Peyron, the tombs of the ancient nomad shepherds. Fara attributes them to an Iberian colony under Norax; Mimaut gives the same origin, and that they were tombs. Petit Radel, imagining them to be tombs, attributes those which have any irregular polygonal masonry to the colony under Iolas and the Thespiadae; and those in which there are only horizontal layers, to the Pelasgi and Tyrrhenians. Inghirami makes them to be funereal monuments with a Tyrrhenian origin; Micali looks to a Phoenician or Carthaginian source, but does not suppose them to be tombs. Arri believes them to be Phoenician, and used in fire worship ;—an opinion entertained also by Miinter and Angius; Manno attributes them to the earliest primitive population,—of Oriental origin, and thinks them tombs of different tribes; Arnim, the places of religious and mystical festivals, and, in later times, burial places. La Marmora reserves his judgment, but implies indirectly that they were of Phoenician origin, and may have served for tombs or temples. Finally, Captain Smyth—the only English author, I believe, who treats of them—and he but slightly, dates their foundation in the obscure ages subsequent to the arrival of the Trojans, after the fall of their city; and supposes “they were designed to answer the double purpose of mausolea for the eminent dead, and asyla for the living.”

It is hardly necessary to notice the utter improbability of the four first opinions, or that they were the residences of families, fortifications, watch-towers, or prisons; for their forms, constructions, and localities are sufficient refutation of such suppositions.

In ascertaining what light is thrown on them directly or indirectly by any ancient authorities, we do not assume the perfect accuracy and veracity of Aristotle, Diodorus Siculus, or Pausanias; but receiving them with a quantum valeat, we will examine their statements.

The words of Aristotle, as the accredited author of the “De Mirabilibus,” are, chapter 104 :--

“It is said that in the island of Sardinia are edifices of the ancients, erected after the Greek manner, and many other beautiful buildings, and tholi (domes or cupolas) finished in excellent proportions. That these were built by Iolaus, the son of Iphicles, when taking the Thespiadae, he sailed to occupy these parts,” &c.

Diodorus Siculus says, lib. iv. chap. 29 and 30:--

“After Iolaus had settled his colony, he sent for Daedalus out of Sicily, and employed him in building many and great works, which remain to this day, and, from the name of the architect, are called Daedalic.”

Again, lib. v. chap. 15, he says, when speaking of the Iolesi:--

“Their captain, Iolaus, possessed himself of the island, and built in it several famous cities, and dividing the country by lot, called the people from himself, Ioleians. He likewise built public schools, and temples of the gods, and everything for the benefit of mankind, of which the remains exist even to these times.”

Pausanias says, lib. x. chap. 17:--

“The first colony was of Libyans under the Libyan Hercules; that they built no towns but lived in huts and caves, being ignorant of the art as the Sardes themselves;” that “a Greek colony under Aristoeus then came, but did not build any city;” that “a colony of Iberians under Norax, the next in succession, built Nora, the first city and that “the fourth colony under Iolaus, composed of Thespians from Attica, built the city of Olbia.”

In reference to Daedalus having been sent for out of Sicily by Iolaus, Pausanias denies it, and makes it to be an anachronism; and in regard to the discrepancy in the different account of the colonies, and origin of the Norax colony, an explanation is elsewhere mentioned; but in endeavouring to collect any thing from the foregoing statements relative to the Noraghe, it is necessary to enter into a further examination of Aristotle’s words, “θολούς” tholus, and “περισσοῖς τοῖς ρυθμοῖς κατεξεσμένους” rhythmis innumeris exornati, “finished in excellent proportions,”—for on them various arguments and conclusions have been formed.

The following is a translation of Meister’s commentary on the words. (Vide Beckman’s edition of Aristotle, Göttingen, 1786, 4to.) :--

“By ‘tholus’ we mean those chambers or roofs, whether hemispherical, circular, elliptical, or angular, which are called by the Italians, Cupole, and by us Kugelgewölbe, Helmgewolbe. The word also appears to apply to other shaped chambers, conically roofed as it were. Some suppose that it was primarily used for only the apex—(de solo summo cuneo)—supporting, binding, and containing the whole arch, afterward for the roof itself, and lastly for the whole building with the roof.

“That round buildings covered with domes were rare in Greece is collected from Pausanias, who mentions only six; under which name it is remarkable that tholus should be applied to those in Sardinia.

“But I do not take these terms to apply simply to the roofs, but to the whole roofed building, and ‘after the manner of the Greeks,’ is placed according to the order of the columns.”

“By ‘rhythmis innumeris exornati,’ I understand worked out in excellent proportions, free from all restrictions, and beautifully finished (perpoliti).”

Beckman says, “that the tholus was that place in the temple from which offerings and trophies were suspended,” quoting Statius, Theb. ii. 734, and the commentary of Lactantius Placidus; and that “rhythmis” were the votive “inscriptions for the recovery of illness, escape from danger,” &c.

Heyne’s opinion is, “From the nature of the text, I think that ‘tholus’ can only be roofs or chambers excellently finished in their proportions.”

Wilkins, in his edition of Vitruvius, page 280, says, “ that the word ‘ tholus’ is generically applied to all buildings of a circular form; and that Vitruvius, iv. 7, and vii. 5, uses it also to signify the roof of a circular edifice. Thus the building at Athens where the Prytanes assembled, the Choragic monument of Lysicrates, a temple at Epidaurus, in which were inscriptions, —rhythmi—referring to the cures performed by Esculapius, and the laconium of a bath, were indiscriminately called ‘tholi.’ But the earliest usage of the word is in Homer, where it appears three times consecutively: ‘Odyssey’ xxii. 442, 459, and 466, in the description of the palace of Ulysses, and means a round building on pillars to keep provisions and kitchen utensils—a vaulted kitchen according to Voss.”

With these various significations and examples, it is impossible to say in what sense Aristotle uses the word; certainly none of them are applicable to a Noraghe, except in the general characteristic of being a round building, and having a dome-roofed chamber. But as this passage of Aristotle has been brought forward so strongly by Radel and other authorities to strengthen their Pelasgic theories, and to confirm their opinions that the Noraghe are of that architecture, it may be observed that Aristotle speaks distinctly of three kinds of buildings, those “of the ancients,” “and many others beautiful,” and “domes and that the grammatical construction in the Greek will hardly admit of the expression “after the Greek manner” being applied to any of them except those “of the ancients.”

But though it is true that in reference to the domes he specifically states them to have been built by Iolaus, and that Diodorus Siculus says that personage built “temples of the gods,” is this sufficient evidence to conclude that the Noraghe were built by the Greeks?

The following objections may be raised to the assumption:—None of these buildings are “finished in excellent proportions,” or have any marks of having had inscriptions, if “ rhythmus” may be so translated. The Pelasgic, Cyclopean, Grecian, and Etruscan buildings are essentially different in their form and arrangement, and except in the latter the cone is little known, still less is it the prominent feature. Those nations have no where left the Sepolture de is Gigantes,—the constant concomitant of the Noraghe. If, according to Pausanias, there were only six domed buildings in Greece, is it probable there would be more than 3,000 built by Grecians in Sardinia?—that with three or four exceptions they should all have been destroyed in the one, and so many have survived in the other country?

It may be safely asserted that no ancient author, except Aristotle, speaks of them, or of any similar to them in other countries.

The researches of Winckelman, Thiersch, Niebuhr, Miinter, Visconti, Botta, Micali, Champollion, Quatremere de Quincey, Drummond, Leake, Gell, Hamilton, Dodwell, Stuart, Hamilton Gray, and Fellows, by their descriptions and explanations of the various ancient architectural remains as extant or restored, instead of throwing any light on these Sarde monuments by analogy, tend to prove their entire difference and dissimilarity.

The controverted points of distinction or identity of the Cyclopean and Pelasgic architecture, will in no way militate against their respective differences from that of the Noraghe; but as the latter have been frequently supposed to be of that date, style, and construction, we may merely refer to the best authenticated specimens of the Cyclopean, namely, Tiryns and Mycene, to refute the supposition.

Their peculiar characteristics are so well known as to require no notice beyond the circumstance of the polygonal style found in them being of a later date than the rest of the building; whereas there are no evidences of different styles of construction in the Noraghe, except in one or two instances, where something of the Cyclopean character exists, from the material of which they are built being so hard as to have evidently defied the few implements used in their construction, and consequently to have produced a slight irregularity in their shape and position. No other remains in Greece, not even the Treasury of Minyas at Orchomenos, nor those structures in Italy and the western coast of Asia Minor, usually called Cyclopean, and to which a Pelasgic origin has been assigned, have any affinity.

The Etruscan buildings, by the description of those no longer existing, as well as from the sepulchres and chambers now known, offer no assistance in the elucidation of the subject, though a few bronze articles have been discovered in them, analogous, though not similar to some relics found in Sardinia and the Balearic Islands; and the existence of the cone has been advanced as an affinity; but the conical tumuli, such as those on Monte Nerone, Cervetri, and in other places, are raised on a narrow stone base, and in every respect differ from the Noraghe.

The observations of Mrs. Hamilton Gray on Etruscan, Pelasgic, and Cyclopean styles, are here very applicable:—“Etruscan architecture is known by very large hewn stones in the form of an oblong square, being joined together with or without cement, and every alternate row meeting in the centre of those below it; or otherwise one row of stones lying lengthways, and the next edgeways, which produces nearly the same effect. Pelasgic, if I understand the term aright, consists of huge hewn blocks cemented or adhering together, but not always quadrilateral or rectangular, whilst the stones of Cyclopean architecture are of all sizes unhewn, and are fitted into each other without cement; being masses of all shapes built together, and adhering by their own weight.”

The form, style, and characteristics of the Indian, Assyrian, and Egyptian architectural remains shew still less resemblance to the Noraghe than either the Cyclopean, Pelasgic, or Etruscan; and the recent discoveries at Nineveh, by Botta, Layard, and Rawlinson, confirm the differences. Nor do the Topes in the Jellalabad country, as described by Masson in Wilson’s “Ariana Antiqua,” assist our enquiries.

On the supposition that the Celtic monuments bear a relation to the Sepolture de is Gigantes, and that the latter are connected with the Noraghe, some relation might be found between the first and last-mentioned remains; but the first premiss is an assumption on which we shall have occasion to offer some remarks.

No buildings are extant in the country known as the ancient Phoenicia, from which any information can be obtained on the style of architecture prevalent there among that people; but we may follow them in their migrations. Among the ruins of Carthage there is not even a vestige analogous to a Noraghe.

Without referring to the Phoenician coins and articles of ornament and use found in Malta, to confirm the statement of Diodorus Siculus, “This island is a colony of the Phoenicians, who, trading to the western ocean, used it as a place of refuge,” (a period assigned by chronologists between 1519 and 1270 b.c), we may mention the Torre del Gigante, in Gozo, attributed by general assent to that people, though its style of masonry has been sometimes considered Cyclopean. The sole resemblance to a Noraghe is in its external form, but the internal and various minutiae indicate a different style and era.

Vide Badger’s description of Malta and Gozo, p. 309; Memoire sur le Temple de Gozo, in the “Nouvelles Annales de la section Francaise de Tlnstitut Archseologique (Premier cahier: Paris, 1828),” “Histoire de Malte, par M. Miège, Bruxelles,” 4 vols. 8vo. Vol. ii. p. 73.

The Balearic Islands, colonised by the Phoenicians, have the Talayots—the only known buildings of a cognate character to those of Sardinia. I much regret having been unable to visit them while at Minorca some years since, being there but a very short time; but the reader is referred to the description given by La Marmora of the few he partially examined; to “Las Antiguedades Celticas de la Isla de Minorca desde los tiempos mas remotos hasta el Siglo IV. de la era Cristiana:—Por el Dn. Dn. Juan Ramis y Ramis, &c., &c., Mahon, 1818;” to “Armstrong’s History of Minorca;” and to the “Voyage aux Isles Baléares, par M. Gresset de Saint Sauveur.”

The Talayots—a diminutive of Atalaya, meaning the Giants’ Burrow—differ from the Noraghe, in that they have only one principal chamber or floor; that the minor lateral coned chambers are unconnected with each other; the style of masonry is more Cyclopean, and that many of them are surrounded with circles of stones and supposed altars, scarcely ever met with in Sardinia, though it is possible they may have existed and are demolished.

On the exterior of one of the Talayots is a ramp ascending to the summit, presumed to have been originally part of the spiral corridor, like that in the Noraghe, but that the outer wall of the building has been destroyed. Armstrong, on the contrary, considering the ramp to have been originally thus built, says that the commodious way by which it was so easily ascended on the outside is a strong argument in favour of the opinion that these structures were used to discover the approach of an enemy, and to warn the natives of their impending danger;—and on this supposition he calls them speculse or watchmounts, as well as repositories of the illustrious dead, for which purpose, he concludes, they were essentially constructed.

Not far from Ciudadela, in the Dels Tudons district, in Minorca, is a building called Nao, from its supposed resemblance to a ship, and considered, with some exceptions, homogeneous with the Sepolture de is Gigantes.

Nearly 200 of these Talayots are extant, but upwards of one-third are in complete ruins.

Independently of bronze ornaments and utensils, apparently of an Etruscan origin, several have been discovered rather similar to those found in Sardinia and Gozo.

Notwithstanding the well-authenticated visits of the “merchants of the sea” to Tarshish, the Spanish coast, their altar at Gades, and temples at Tartessus, Spain possesses no memorial of a Noraghic character. We will next see the supposed affinity to the Round Towers in Ireland, but without examining the contested points of their founders and purposes,—whether Phoenician, Danish, Pagan, or Christian, or used as beacons, belfries, penitentiaries, anchorite towers, repositories of church utensils, minarets for calling to prayer, monuments of the principal establishers of Christianity, episcopal indices to point out the cathedrals, Pagan sepulchral monuments, or temples of the fire worshippers,—according to the several opinions entertained by different authors.

Their number has been variously stated from eighty-three to 118; the supposed points of similarity are, that they are round, divided into stories, have a conical arched roof of mason work, that articles of metallurgy and bodies have been found in them, and finally that their vernacular name, Cill-gagh or Golcagh, is said to mean fire and divinity.

But in these very peculiarities it must be observed respectively of them that they are not more than from eight to fifteen feet in diameter; the stories are generally marked off with exterior bands or beltings; the roof is invariably formed of overlaying stones, in the manner of inverted steps; that the articles found are peculiar in themselves; and that the bodies were discovered under the floorings;—all points of dissimilarity to those of the Sarde buildings. The interpretation of the name as connected with fire, to which the word Nor-aghe is also said to refer, is the only coincidence of any importance. The points of positive dissimilarity are, that independently of being only from eight to fifteen feet in diameter, they are from 70 feet to 130 high; that they have a circular projecting base with a plinth, the stones are elaborately cut, joined with, though sometimes without, cement; and that, though closely fitting to each other, they are not in regular horizontal layers. The door is from six to fifteen feet above the ground, varies in position, is broad at base, narrow at top, or semicircular or lancet arched; and is usually ornamented with bands on the external face of the architrave; there is no spiral ramp or ascent; each floor is lighted by a window, and the upper story by four or six windows, facing the cardinal points; sculpture is found in parts, and also ornaments, as chevron work over the doorways; and, in regard to position, they are almost always found near churches.

The Boens in Kerry have a certain affinity, but too remote to assist us.

The tumulus of New Grange, on the banks of the Boyne, between Drogheda and Slane, County Meath, should not be left unmentioned. It was discovered in 1699 under a mound covering nearly two acres in extent, and made of stone, with a slight coating of earth. A long, narrow passage, not more than one foot six inches high and two feet broad, led to a chamber,—thus described by Mr. Petrie:--

“It is about twenty-two feet in diameter, covered with a dome of a bee-hive form, constructed of massive stones laid horizontally, and projecting one beyond the other till they approximate, and are finally capped with a single one; the height of the dome is about twenty feet, the chamber has three quadrangular recesses forming a cross, one facing the entrance gallery and one on each side. In each of these recesses is placed a stone urn or sarcophagus, of a simple bowl form, two of which remain. Of these recesses, the east and west are about eight feet square, the north is somewhat deeper. The entire length of the cavern, from the entrance of the gallery to the end of the recess, is eighty-one feet eight inches.” The building has various marks of sculpture—some of even refined workmanship—but none of the Ogham character.

No notice need be made of the numberless cromlechs in Ireland, beyond their existence and disconnection with the Round Towers; nor of the many relics discovered and attributed to a Phoenician origin.

The Scottish Dunes are circular towers, but the internal arrangements are entirely different; and their comparatively modern date and purposes are generally conceded.

The Dune of Dornadilla, in the parish of Duirnes, on Lord Reay’s estate at Strathmore, at first presents a Noraghic appearance; but the description by the Rev. Alexander Pope, in a letter to George Peton, dispels the expected similitude.

It has been assumed that the remnant of the Tyrians, who were to be saved according to the prophecy of Isaiah (chaps, xxiii. and xxiv.), migrated on the fall of Tyre, B.C. 332; and that, according to the other prophecy (Isaiah xxiii. 7) : — “ Her own feet shall carry her afar off to sojourn,” they reached Central America, and there founded the cities of Copan, Uxmel, Palanque, and Santa Cruz del Quiche; but it is perfectly evident, from the works of Lord Kingsborough and Mr. Stephens, that those wonderful remains, whether of Tyrian origin or not, have no characteristics to identify them with the genus and style of the Noraghe. The only points requiring notice are the records and description of a large altar called El Sacrificatorio, having been used for sacrifices similar to those of the Phoenicians, and of the Israelitish and Canaanitish origin of the people.

We must give the words of Mr. Stephens:—” El Sacrificatorio, or the Place of Sacrifice, is a quadrangular stone structure, sixty-six feet on each side at the base, and rising in a pyramidal form to the height, in its present condition, of thirty-three feet. On three sides there is a range of steps in the middle, each step seventeen inches high, and but eight inches on the upper surface, which makes the range so steep that in descending some caution is necessary. At the corners are four buttresses of cut stone, diminishing in size from the line of the square, and apparently extended to support the structure. On the side facing the west there are no steps, but the surface is smooth and covered with stucco, gray from long exposure. By breaking a little off the corners we saw that there were different layers of stucco, doubtless put on at different times, and all had been ornamented with painted figures. In one place we made out part of the body of a leopard, well drawn and coloured. The top of the Sacrificatorio is broken and ruined, but there is no doubt that it once supported an altar for those sacrifices of human victims which struck even the Spaniards with horror. It was barely large enough for the altar and officiating priests, and the idol to whom the sacrifice was offered. The whole was in full view of the people at the foot.”

Without entering into the records of the Toltecas, or into Mr. Jones’ theories in his “ History of Ancient America,” that in the North American Indians may be found one of the lost tribes of Israel, and that the Tyrians were the early inhabitants of Central America, it may be mentioned that many of the paintings and portions of sculpture found on the walls and among the ruins of the ancient cities, are said to represent the human sacrifices made to Moloch and Baal; but, whether rightly or wrongly interpreted, they bear an analogy to the Sarde idols, though the Sacrificatorio in its form and style, has none to the Noraghe; and it is on account of the former curious coincidence that the details of the latter have been here extracted from Mr. Stephens’ work.

Having hitherto endeavoured to shew by negatives what these Sarde remains are unlike, and to find where and in what respect any buildings in other countries are most analogous to them, we can only arrive at the full belief of the non-existence of their exact counterparts elsewhere, and that the Talayots in the Balearic Islands have the nearest affinity.

Devoid of any positive light as to their origin or purpose, the results of speculation and conjecture have hitherto been most unsatisfactory; for, in all the researches and investigations, some points of difference, discrepancy, and refutation, have arisen to nullify the various hypotheses which have been formed from the existence of certain facts, from the combination of peculiar circumstances, from intrinsic characteristics, and from extrinsic evidence and analogy.

We may reduce the enquiry to the simple questions, Were the Noraghe built by the autochthones of the island, of whom we have no knowledge, or by the earliest colonists, of whom we have but little information; and, in either case, for what purpose did they serve?

That they may have been the religious or sepulchral monuments of the autochthones is certainly the safest supposition, for it can meet with but little refutation, owing to the paucity of argument to prove them any thing else.

But without asserting either from negative arguments or from baseless fabrics of archaeological hypotheses, a probability may be shewn of their very ancient eastern origin. Their wonderful strength and solidity, uniformity of design, though difference in size, the peculiar direction and smallness of the entrance, the narrow winding passages, domed chambers, position on a natural or artificial elevation, whether on hills or in valleys, the small aperture for the admission of light, and the circumstances of the Sepoltura de is Gigantes being concomitant remains, are peculiarities which evidently indicate a religious or sepulchral purpose. Comparatively but very few are so constructed as to permit the supposition of their having been merely sepulchres; but there is nothing in their shape to render it impossible that they may have been altars or temples for the worship of the heavenly bodies, or for the earliest sacrifices and idolatries recorded in the Old Testament.

But how could these have reached Sardinia? When was there a migration of any of the earliest people westward, by which such customs could have been imported into the island?

Though there is no express mention of their having reached Sardinia, there is sufficient collateral evidence to warrant the assumption.

Among the various migrations mentioned in the Old Testament, it is now clearly understood that the Philistines, when the very early eastern tide of population pressed on them, quitted the mainland for the islands; and that they inhabited Crete and subsequently returned to their native land before the date of Moses.

The Hebrew word Philistine meaning wanderer, in the Septuagint, is translated by “men of another tribe.” God says, (Amos ix. 7,) “Have I not brought the Philistines from Caphtor?” In Jeremiah (xlvii. 4), they are called “the remnant of the country (or isle) of Caphtor;” but for evidence of the identity of the Caphtorim and Philistim, that the island of Crete was peopled by them, and for the supposition that Caphtor was Crete, vide the condensed and learned authorities in Kitto’s Cyclopaedia of Biblical literature.

It should be remembered, moreover, that the religion of the Philistines was very analogous to that of the Phoenicians.

That Cyprus was peopled by the very early Phoenician colonies is indisputably proved; and that it was previously occupied by the Chittim,—the descendants of Javan, the son of Japhet (Genesis x. 4), is almost equally certain. The word Chittim has been considered by some commentators to have been applied in some passages of holy writ to the islands of the Mediterranean collectively, but there are specific occasions in which it evidently means Cyprus; and it is recorded by various writers that the town of Citium—the modern Chitti—was built by the Chittim. The well-known Phoenician inscriptions found there, offer no elucidation of the subject before us, beyond the mention of a temple of Astarte, (vide Gesenius lib. ii. ch. 3. Inscriptions Citienses) and some other deities of that nation.

In regard to Sicily, it is specifically stated by Thucydides, lib. vi., to have been occupied by the Phoenicians; and the names of many towns and places, not a vestige of which remains, indicate that origin. But it was at an early period; and the same causes of destruction which have swept them away, have left but few of the Greek and Roman monuments erected by those nations during their dominion in the island.

But how is it that neither Noraghe nor Sepolture de is Gigantes are found in Corsica—apparently the sister island of Sardinia? Was it unknown to the Canaanites and Phoenicians? It certainly is not mentioned by either sacred or profane writers till a comparatively late period; and Bochart observes, “It is doubtful whether the Phoenicians occupied Corsica, nor do the ancients inform us in sufficiently express terms.” (Lib. i. ch. 32.) The earliest mention is by Herodotus, who says a colony from Phocsea in Asia Minor founded Alalia, about 564 B.c.; and Polybius in speaking of the Carthaginians merely says they obtained possession of the islands in the Sardinian and Tyrrhenian seas; but previous to these dates there is no evidence of a Phoenician, still less of an earlier people having occupied it.

The Phoenician, a branch of the great Semitic or Aramsean nations, originally dwelt, according to Herodotus, on the shores of the Erythrean sea; but Strabo says there were two islands in the Persian Gulf, Tyrus or Tylus and Aradus on which were found temples, similar to those of the Phoenicians, and inhabitants who affirmed that the Phoenicians went out from them as colonists, though the period is unknown, but it must have been very early, as Sidon was a great city in the time of Joshua, 1444 B.c.

It is clearly ascertained, too, that the original inhabitants of Tyre and Sidon had been expelled from their cities before the time of Joshua, and that the occupants in his time were a distinct people from the Canaanites.

In either case the expulsion and migration of those people did occur, and there is no reason to doubt that the religion of both the Canaanites and Phoenicians was of a similarly pagan and idolatrous character.

Besides the seven tribes of the Canaanites specifically mentioned to be dispossessed wholly or partially by the Israelites, many living to the north of the promised land were also exterminated either by sword or expulsion. There is no positive mention of the countries to which they fled on the approach of Moses, but that among their migrations some went to Africa on the approach of Joshua is known by historical evidence and tradition. Procopius states that there were at Tigisis-Tingis, in Mauritania, two columns on which were inscribed in Phoenician characters, “We are those who fled from the face of Joshua the robber, the son of Naue.”

St. Augustin—1900 years after a migration of the Phoenicians into Libya, states that the people about Carthage and Hippo still called themselves Canaanites; and Eusebius mentions that Tripoli was colonised by the Canaanites, whom the Israelites drove out of their country.

Though the Phoenicians have left no memorials at Tartessus, it may be here repeated that, on their arrival on the Spanish coast, they found a town of that name already existing, and that it is considered to have been founded by the migrating descendants of Tarshish, the grandson of Japhet (Gen. x. 4), as Cyprus has been shewn to have been peopled by a race from his brother Chittim. From this Tartessus is said to have proceeded the so called Iberian colony, under Norax to Sardinia. “By these were the isles of the Gentiles divided.” Genesis x. 5.

The direction of the Canaanitish emigrations might also be assumed from the probability that the Phoenicians may have followed their example and footsteps; and as the expression of Diodorus Siculus, lib. v., relative to Phoenician colonies migrating, “ some to Sicily and the neighbouring islands, some to Libya and Sardinia and Iberia,” is proved by Phoenician coins, inscriptions, and other remains found in those places, it may be an additional ground of presumption of their previous occupation by some Canaanitish colony.

But neither the sacred nor profane writers of antiquity give any account of the form of the temples of the early Canaanitish and Phoenician nations; and those mentioned in later times, such as the temple of Astarte at Ascalon, destroyed by the Scythians 630 B.C., might naturally be very different to those erected at an earlier period, as the religions of the Aramsan families were changed and diversified from their primitive simplicity to the various forms in which they were found in subsequent periods in different countries.

Jahn observes, that “every nation and city had its own gods, which at first acquired some celebrity by the worship of some particular family merely, but were at length worshipped by the other families of that city or nation, yet each family had its separate household or tutelary gods.” The erection therefore of temples by colonists in a new country would differ according to their peculiar legends and worship of a chief or deity, and be dependent on the nature of the soil, climate, and a variety of circumstances. It may be argued that no positive similarity between the Noraghe and the idolatrous temples of the colonies from the Canaanitish and Phoenician nations can be proved by history, or by any extant remains; but it may be answered, that it is rather by the non-existence of such buildings in those countries which were ravaged and destroyed, and whose inhabitants were expatriated according to prophecy,—by the sole existence of them in a direction to which those inhabitants migrated,—and by the knowledge that other nations adopted and have left monuments and records of a dissimilar style and character, that the hypothesis of the Canaanitish origin of the Noraghe may be strengthened.

The Carthaginian occupation of the island, and the “a Poenis admixto Afrorum genere Sardi” need here only be mentioned in reference to their custom of sacrificing children to Saturn.

Justinian states, that ambassadors went to the Carthaginians from Darius, circa 500 B.C., with an edict to prevent the immolation of human beings; and that a cessation of such practices formed part of the terms of peace between them and Gelon, circa 480 B.C. Sardinia was at this period previously occupied by them, and if the Noraghe were at all connected with these sacrifices, their disuse and decay might have then commenced.

These customs were undoubtedly inherited from the Phoenicians; and as those “merchants of many isles” and the Japhetian nations had analogous principles of idolatry in their religions, a descent and affinity may be traced through and between the Carthaginian, Phoenician, Canaanitish, and Japhetian forms of worship.

In regard to this Saturn, Jahn says, “he devoured his own offspring, a circumstance of which indeed we have an imitation in the custom of offering children to him in sacrifice, which existed among the Canaanites, Phoenicians, and Carthaginians, by whom he was known under the various names of Moloc, Molec, Malcom, and Milcom.

The cruel and intolerant creed of the Carthaginians, as we know by their recorded destruction of crops and prohibition of the renewal beyond a certain quantity in Sardinia, would not probably have spared the temples and religion of the inhabitants had they been dissimilar to their own; so that their non-destruction of them may be a presumptive evidence of the similarity, if not identity of worship, and that they possibly used the Noraghe for the same or cognate ceremonies, which had been introduced centuries previously by their progenitors and predecessors.

On the Roman conquest of the island, and expulsion of the Carthaginians, we may fairly suppose these buildings to have been no longer used for religious purposes; and an evidence of it is found at a Noraghe at Pula, where an aqueduct was built by the Romans on its ruins.

In speaking of those extraordinary antiquities, known as the Sarde Idols, we shall attempt to shew that the greater part of them were of Canaanitish worship—the miniature representation of some of the large and original gods which those nations adored—especially of Moloch, Baal, Astarte or Astaroth, Adonis or Tammuz; the very objects of that idolatry so frequently and emphatically denounced in the Old Testament. Distinct and peculiar in their character, their counterparts are no more to be met with out of Sardinia, than the Noraghe themselves; and this circumstance, in conjunction with the fact that many of them have been found in, and the greater part near those buildings, may suggest a further proof that they may have been directly or indirectly connected with each other, in either a religious, sepulchral, or united character.

The few other articles hitherto discovered are of common pottery, apparently Carthaginian and Roman; some pieces of porphyry, of a wedge shape, like a stonebreaker’s hammer; and others of the same material which were probably sharpening stones. They reminded me of those in the Icelandic collection in the Museum at Copenhagen, the natives of which island used them before the introduction of metal implements.

The Sepolture de is Gigantes—the tombs of the giants—another of the antiquities of the island, may also be alluded to, though the subject is fully mentioned presently.

If a Canaanitish race migrated here, nothing is more probable than that the tradition and worship of the Giants would be also imported; nay, it is even possible that some of the actual gigantic races of Rephaim, Anakim, Philistines, Emim, or Zamzummim might have actually arrived in Sardinia.

Though Sarde traditions sanction such a belief, it is evident that the Giants and Noraghe were not directly connected, because they never could have entered them, but on the supposition that a Canaanitish colony may have erected tombs as monuments to the memory of a chief or hero, characteristic of and proportionate to the reality or legend of his size, the Noraghe and Sepolture might be connected with each other as buildings erected by the same people.

On these last grounds an affinity may also be traced to the Perdas Fittas and Conical Stones, both assumed to have an eastern origin.

The etymology of the word Noraghe or Nurhag may strengthen the supposition of their ancient and eastern origin, and religious purpose. The Abbé Arri consi ders it a Phoenician or Carthaginian word, and of which the Hebrew or rather Chaldee [HEBREW CHARACTERS] fire, is the root.

If pronounced without the n, Our-ag, or Ur-ag, it might indicate a similar allusion to fire or light; and the words of Nimrod, though referring to a very different subject, may be quoted as explanatory:—“The appearance of fire and solar light is like that of gold, which metal did by its colour and brightness obtain the name of ‘aour’—the or of France, oro of Spain and Italy, aurum of the Latins, and ouron of the Greeks; the word aour, our, ur, meaning light or fire—the urim of the Lord—the ouranon of the Greeks—the urere of the Latins.”

By some the words νεοραχις, “a new rock,” and νεῦρα ἐχεῖν, “having strength” (loosely translated), and by others Norax the founder of an Iberian colony, have been also given as derivations.

Without entering into Gesenius’s observations on 2 Kings xxiii. 5, it is allowed that the Canaanr Hish and Phoenician god, Baal, was the sun, as Astaroth was the moon, and was worshipped as the first principle,—the heat and light of life,—before Moses entered those countries; and as such, the names Nurhag and Our-ag might possibly have descended from some Phoenician or Aramaean word, indicative of the worship and attributes of the deity, or in some way referable to the buildings. They could not have been applied to the worship of the element itself in later periods, as the Persians and other fire-worshippers never used buildings or idols. Vide Herod: i. 131.

The name of several Noraghe, “Adoni,” reminds one of Adonis, the Osiris of the Egyptians, the Tammuz of the Canaanites, that deity whose idolatrous festival is mentioned by Ezekiel (viii. 14); besides its usage and signification in other places in the Old Testament.

These circumstances have not been adduced as proofs, but merely as etymological coincidences and arguments.

The last point of consideration is how far these buildings are adapted for such idolatrous and sacrificial purposes; and little can be gained by the enquiry.

Various kinds of altars are spoken of in the Old Testament; some, low on the ground, others in high places, and on the tops of buildings. Vide 1 Kings xviii. 26; Jeremiah xix. 5, and xxxii. 29; Zephaniah i. 5.

The Noraghe, as previously mentioned, are all built on a raised base; they are high, and the platform on their summit might be well adapted for sacrifice; but it would be mere fanciful speculation to attempt any explanation of the domed chambers, passages, and parts of the building, as there is no standard by which any test or comparison could be applied.

The various articles discovered in them tend to prove a sacrificial and religious, rather than a sepulchral, character of building; and in regard to the cells and recesses in the chambers, it should be observed that a large portion of the Noraghe have none, and those which exist are so irregular in size and shape that they convey no idea of graves or burial places. Some might certainly have served, but others are not large enough for that purpose.

The human remains occasionally found in them, have not had any indication of embalment, or any other process by which they could have existed between 3000 and 4000 years.

In concluding this subject it must be repeated, in answer to the natural question which may arise, why are there no traces of similar remains in those countries where the Canaanitish and Phoenician nations dwelt? that the fulfilment of the express law of God and the prophecies would account for these monuments having been swept off the face of those countries, no less than for the expulsion of the inhabitants; and the fact that scarcely any are found in the countries whither they emigrated, may be accounted for by the circumstance that these nations have all been subjected to the fire, sword, and destruction of invaders and enemies, to a degree in comparison to which Sardinia has suffered but little in ancient times.

We have now endeavored to arrive at the conclusion that these extraordinary monuments were probably temples of sacrifice and worship, built by the very early Canaanites, in their migration when expelled from their country; and that as such they may have been occasionally used as a depository of the idols, or remains of the immolated victims, or even of some exalted personages connected with their worship and rites.

These deductions, made from hypotheses, open to refutation, and from inferences worked by a negative process, remain to be disproved by positive facts and clear evidence of what the buildings are.

The author has only to remark, that having seen many of the antiquities in Asia Minor, and the greater part of those in the different countries in Europe, he can safely recommend the Noraghe to the attention of antiquaries and travellers, feeling confident that though Assyrian, Babylonian, Egyptian, Cyclopean, Pelasgic, Etrurian, Greek, and Roman remains are so far superior in extent, workmanship, ornament, and historical associations, none of them have that charm of mystery which, as a halo, emanates from, and enshrouds those of Sardinia.

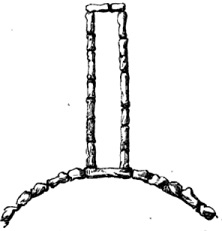

The Sepolture de is Gigantes, to which we shall have occasion to allude, now demand a brief but general explanation, though the minor details and differences are mentioned in their respective localities.

The Padre Angius has subdivided the Noraghe into four categories—the simple cones, the compound, the united, and those having outworks. These subdivisions would, however, be insufficient; for, though in their general characteristics the buildings have the closest affinity to each other, the minor points of difference are so varied and numerous, and the dilapidations have so altered their form and appearance, that any classification might not only be confusing but possibly erroneous.

Though there are upwards of 3000 now in existence, more or less in ruins, it may be fairly assumed that they were formerly more numerous, for though there is not the slightest ground for supposing that any have been built during the last 2500 years, there is evidence to prove that their destruction has been gradual and progressive. Forming a valuable quarry for the people in making their houses, chiudende or enclosures, and roads, every day’s spoliation so alters their appearance, that future travellers may not recognise those described by their predecessors; and another difficulty arises in the variety of names given to the same Noraghe, so that the information from the peasants is constantly though unintentionally incorrect, and productive of incessant mistakes. In general, they are called after some saint or personage, peculiar feature in the building, or proximity to a well known object, such as San Gavinu, ederosu, de tres bias, &c.

La Marmora has given details and admirable plans of several of the principal Noraghe, some of which will be mentioned in the following pages, together with those remarkable for any peculiar feature, selected from upwards of fifty that I measured.

The consideration of their origin and purpose may be prefaced by the abridged opinions of the authors who have hitherto entered upon the subject.

Stephanini believes them to have been trophies of victory; Vidal, the houses of the giants; Madao, the tombs of the antediluvians; Peyron, the tombs of the ancient nomad shepherds. Fara attributes them to an Iberian colony under Norax; Mimaut gives the same origin, and that they were tombs. Petit Radel, imagining them to be tombs, attributes those which have any irregular polygonal masonry to the colony under Iolas and the Thespiadae; and those in which there are only horizontal layers, to the Pelasgi and Tyrrhenians. Inghirami makes them to be funereal monuments with a Tyrrhenian origin; Micali looks to a Phoenician or Carthaginian source, but does not suppose them to be tombs. Arri believes them to be Phoenician, and used in fire worship ;—an opinion entertained also by Miinter and Angius; Manno attributes them to the earliest primitive population,—of Oriental origin, and thinks them tombs of different tribes; Arnim, the places of religious and mystical festivals, and, in later times, burial places. La Marmora reserves his judgment, but implies indirectly that they were of Phoenician origin, and may have served for tombs or temples. Finally, Captain Smyth—the only English author, I believe, who treats of them—and he but slightly, dates their foundation in the obscure ages subsequent to the arrival of the Trojans, after the fall of their city; and supposes “they were designed to answer the double purpose of mausolea for the eminent dead, and asyla for the living.”

It is hardly necessary to notice the utter improbability of the four first opinions, or that they were the residences of families, fortifications, watch-towers, or prisons; for their forms, constructions, and localities are sufficient refutation of such suppositions.

In ascertaining what light is thrown on them directly or indirectly by any ancient authorities, we do not assume the perfect accuracy and veracity of Aristotle, Diodorus Siculus, or Pausanias; but receiving them with a quantum valeat, we will examine their statements.

The words of Aristotle, as the accredited author of the “De Mirabilibus,” are, chapter 104 :--

“It is said that in the island of Sardinia are edifices of the ancients, erected after the Greek manner, and many other beautiful buildings, and tholi (domes or cupolas) finished in excellent proportions. That these were built by Iolaus, the son of Iphicles, when taking the Thespiadae, he sailed to occupy these parts,” &c.

Diodorus Siculus says, lib. iv. chap. 29 and 30:--

“After Iolaus had settled his colony, he sent for Daedalus out of Sicily, and employed him in building many and great works, which remain to this day, and, from the name of the architect, are called Daedalic.”

Again, lib. v. chap. 15, he says, when speaking of the Iolesi:--

“Their captain, Iolaus, possessed himself of the island, and built in it several famous cities, and dividing the country by lot, called the people from himself, Ioleians. He likewise built public schools, and temples of the gods, and everything for the benefit of mankind, of which the remains exist even to these times.”

Pausanias says, lib. x. chap. 17:--

“The first colony was of Libyans under the Libyan Hercules; that they built no towns but lived in huts and caves, being ignorant of the art as the Sardes themselves;” that “a Greek colony under Aristoeus then came, but did not build any city;” that “a colony of Iberians under Norax, the next in succession, built Nora, the first city and that “the fourth colony under Iolaus, composed of Thespians from Attica, built the city of Olbia.”

In reference to Daedalus having been sent for out of Sicily by Iolaus, Pausanias denies it, and makes it to be an anachronism; and in regard to the discrepancy in the different account of the colonies, and origin of the Norax colony, an explanation is elsewhere mentioned; but in endeavouring to collect any thing from the foregoing statements relative to the Noraghe, it is necessary to enter into a further examination of Aristotle’s words, “θολούς” tholus, and “περισσοῖς τοῖς ρυθμοῖς κατεξεσμένους” rhythmis innumeris exornati, “finished in excellent proportions,”—for on them various arguments and conclusions have been formed.

The following is a translation of Meister’s commentary on the words. (Vide Beckman’s edition of Aristotle, Göttingen, 1786, 4to.) :--

“By ‘tholus’ we mean those chambers or roofs, whether hemispherical, circular, elliptical, or angular, which are called by the Italians, Cupole, and by us Kugelgewölbe, Helmgewolbe. The word also appears to apply to other shaped chambers, conically roofed as it were. Some suppose that it was primarily used for only the apex—(de solo summo cuneo)—supporting, binding, and containing the whole arch, afterward for the roof itself, and lastly for the whole building with the roof.

“That round buildings covered with domes were rare in Greece is collected from Pausanias, who mentions only six; under which name it is remarkable that tholus should be applied to those in Sardinia.

“But I do not take these terms to apply simply to the roofs, but to the whole roofed building, and ‘after the manner of the Greeks,’ is placed according to the order of the columns.”

“By ‘rhythmis innumeris exornati,’ I understand worked out in excellent proportions, free from all restrictions, and beautifully finished (perpoliti).”

Beckman says, “that the tholus was that place in the temple from which offerings and trophies were suspended,” quoting Statius, Theb. ii. 734, and the commentary of Lactantius Placidus; and that “rhythmis” were the votive “inscriptions for the recovery of illness, escape from danger,” &c.

Heyne’s opinion is, “From the nature of the text, I think that ‘tholus’ can only be roofs or chambers excellently finished in their proportions.”

Wilkins, in his edition of Vitruvius, page 280, says, “ that the word ‘ tholus’ is generically applied to all buildings of a circular form; and that Vitruvius, iv. 7, and vii. 5, uses it also to signify the roof of a circular edifice. Thus the building at Athens where the Prytanes assembled, the Choragic monument of Lysicrates, a temple at Epidaurus, in which were inscriptions, —rhythmi—referring to the cures performed by Esculapius, and the laconium of a bath, were indiscriminately called ‘tholi.’ But the earliest usage of the word is in Homer, where it appears three times consecutively: ‘Odyssey’ xxii. 442, 459, and 466, in the description of the palace of Ulysses, and means a round building on pillars to keep provisions and kitchen utensils—a vaulted kitchen according to Voss.”

With these various significations and examples, it is impossible to say in what sense Aristotle uses the word; certainly none of them are applicable to a Noraghe, except in the general characteristic of being a round building, and having a dome-roofed chamber. But as this passage of Aristotle has been brought forward so strongly by Radel and other authorities to strengthen their Pelasgic theories, and to confirm their opinions that the Noraghe are of that architecture, it may be observed that Aristotle speaks distinctly of three kinds of buildings, those “of the ancients,” “and many others beautiful,” and “domes and that the grammatical construction in the Greek will hardly admit of the expression “after the Greek manner” being applied to any of them except those “of the ancients.”

But though it is true that in reference to the domes he specifically states them to have been built by Iolaus, and that Diodorus Siculus says that personage built “temples of the gods,” is this sufficient evidence to conclude that the Noraghe were built by the Greeks?

The following objections may be raised to the assumption:—None of these buildings are “finished in excellent proportions,” or have any marks of having had inscriptions, if “ rhythmus” may be so translated. The Pelasgic, Cyclopean, Grecian, and Etruscan buildings are essentially different in their form and arrangement, and except in the latter the cone is little known, still less is it the prominent feature. Those nations have no where left the Sepolture de is Gigantes,—the constant concomitant of the Noraghe. If, according to Pausanias, there were only six domed buildings in Greece, is it probable there would be more than 3,000 built by Grecians in Sardinia?—that with three or four exceptions they should all have been destroyed in the one, and so many have survived in the other country?

It may be safely asserted that no ancient author, except Aristotle, speaks of them, or of any similar to them in other countries.

The researches of Winckelman, Thiersch, Niebuhr, Miinter, Visconti, Botta, Micali, Champollion, Quatremere de Quincey, Drummond, Leake, Gell, Hamilton, Dodwell, Stuart, Hamilton Gray, and Fellows, by their descriptions and explanations of the various ancient architectural remains as extant or restored, instead of throwing any light on these Sarde monuments by analogy, tend to prove their entire difference and dissimilarity.

The controverted points of distinction or identity of the Cyclopean and Pelasgic architecture, will in no way militate against their respective differences from that of the Noraghe; but as the latter have been frequently supposed to be of that date, style, and construction, we may merely refer to the best authenticated specimens of the Cyclopean, namely, Tiryns and Mycene, to refute the supposition.

Their peculiar characteristics are so well known as to require no notice beyond the circumstance of the polygonal style found in them being of a later date than the rest of the building; whereas there are no evidences of different styles of construction in the Noraghe, except in one or two instances, where something of the Cyclopean character exists, from the material of which they are built being so hard as to have evidently defied the few implements used in their construction, and consequently to have produced a slight irregularity in their shape and position. No other remains in Greece, not even the Treasury of Minyas at Orchomenos, nor those structures in Italy and the western coast of Asia Minor, usually called Cyclopean, and to which a Pelasgic origin has been assigned, have any affinity.

The Etruscan buildings, by the description of those no longer existing, as well as from the sepulchres and chambers now known, offer no assistance in the elucidation of the subject, though a few bronze articles have been discovered in them, analogous, though not similar to some relics found in Sardinia and the Balearic Islands; and the existence of the cone has been advanced as an affinity; but the conical tumuli, such as those on Monte Nerone, Cervetri, and in other places, are raised on a narrow stone base, and in every respect differ from the Noraghe.

The observations of Mrs. Hamilton Gray on Etruscan, Pelasgic, and Cyclopean styles, are here very applicable:—“Etruscan architecture is known by very large hewn stones in the form of an oblong square, being joined together with or without cement, and every alternate row meeting in the centre of those below it; or otherwise one row of stones lying lengthways, and the next edgeways, which produces nearly the same effect. Pelasgic, if I understand the term aright, consists of huge hewn blocks cemented or adhering together, but not always quadrilateral or rectangular, whilst the stones of Cyclopean architecture are of all sizes unhewn, and are fitted into each other without cement; being masses of all shapes built together, and adhering by their own weight.”

The form, style, and characteristics of the Indian, Assyrian, and Egyptian architectural remains shew still less resemblance to the Noraghe than either the Cyclopean, Pelasgic, or Etruscan; and the recent discoveries at Nineveh, by Botta, Layard, and Rawlinson, confirm the differences. Nor do the Topes in the Jellalabad country, as described by Masson in Wilson’s “Ariana Antiqua,” assist our enquiries.

On the supposition that the Celtic monuments bear a relation to the Sepolture de is Gigantes, and that the latter are connected with the Noraghe, some relation might be found between the first and last-mentioned remains; but the first premiss is an assumption on which we shall have occasion to offer some remarks.

No buildings are extant in the country known as the ancient Phoenicia, from which any information can be obtained on the style of architecture prevalent there among that people; but we may follow them in their migrations. Among the ruins of Carthage there is not even a vestige analogous to a Noraghe.

Without referring to the Phoenician coins and articles of ornament and use found in Malta, to confirm the statement of Diodorus Siculus, “This island is a colony of the Phoenicians, who, trading to the western ocean, used it as a place of refuge,” (a period assigned by chronologists between 1519 and 1270 b.c), we may mention the Torre del Gigante, in Gozo, attributed by general assent to that people, though its style of masonry has been sometimes considered Cyclopean. The sole resemblance to a Noraghe is in its external form, but the internal and various minutiae indicate a different style and era.

Vide Badger’s description of Malta and Gozo, p. 309; Memoire sur le Temple de Gozo, in the “Nouvelles Annales de la section Francaise de Tlnstitut Archseologique (Premier cahier: Paris, 1828),” “Histoire de Malte, par M. Miège, Bruxelles,” 4 vols. 8vo. Vol. ii. p. 73.

The Balearic Islands, colonised by the Phoenicians, have the Talayots—the only known buildings of a cognate character to those of Sardinia. I much regret having been unable to visit them while at Minorca some years since, being there but a very short time; but the reader is referred to the description given by La Marmora of the few he partially examined; to “Las Antiguedades Celticas de la Isla de Minorca desde los tiempos mas remotos hasta el Siglo IV. de la era Cristiana:—Por el Dn. Dn. Juan Ramis y Ramis, &c., &c., Mahon, 1818;” to “Armstrong’s History of Minorca;” and to the “Voyage aux Isles Baléares, par M. Gresset de Saint Sauveur.”

The Talayots—a diminutive of Atalaya, meaning the Giants’ Burrow—differ from the Noraghe, in that they have only one principal chamber or floor; that the minor lateral coned chambers are unconnected with each other; the style of masonry is more Cyclopean, and that many of them are surrounded with circles of stones and supposed altars, scarcely ever met with in Sardinia, though it is possible they may have existed and are demolished.

On the exterior of one of the Talayots is a ramp ascending to the summit, presumed to have been originally part of the spiral corridor, like that in the Noraghe, but that the outer wall of the building has been destroyed. Armstrong, on the contrary, considering the ramp to have been originally thus built, says that the commodious way by which it was so easily ascended on the outside is a strong argument in favour of the opinion that these structures were used to discover the approach of an enemy, and to warn the natives of their impending danger;—and on this supposition he calls them speculse or watchmounts, as well as repositories of the illustrious dead, for which purpose, he concludes, they were essentially constructed.

Not far from Ciudadela, in the Dels Tudons district, in Minorca, is a building called Nao, from its supposed resemblance to a ship, and considered, with some exceptions, homogeneous with the Sepolture de is Gigantes.

Nearly 200 of these Talayots are extant, but upwards of one-third are in complete ruins.

Independently of bronze ornaments and utensils, apparently of an Etruscan origin, several have been discovered rather similar to those found in Sardinia and Gozo.

Notwithstanding the well-authenticated visits of the “merchants of the sea” to Tarshish, the Spanish coast, their altar at Gades, and temples at Tartessus, Spain possesses no memorial of a Noraghic character. We will next see the supposed affinity to the Round Towers in Ireland, but without examining the contested points of their founders and purposes,—whether Phoenician, Danish, Pagan, or Christian, or used as beacons, belfries, penitentiaries, anchorite towers, repositories of church utensils, minarets for calling to prayer, monuments of the principal establishers of Christianity, episcopal indices to point out the cathedrals, Pagan sepulchral monuments, or temples of the fire worshippers,—according to the several opinions entertained by different authors.

Their number has been variously stated from eighty-three to 118; the supposed points of similarity are, that they are round, divided into stories, have a conical arched roof of mason work, that articles of metallurgy and bodies have been found in them, and finally that their vernacular name, Cill-gagh or Golcagh, is said to mean fire and divinity.

But in these very peculiarities it must be observed respectively of them that they are not more than from eight to fifteen feet in diameter; the stories are generally marked off with exterior bands or beltings; the roof is invariably formed of overlaying stones, in the manner of inverted steps; that the articles found are peculiar in themselves; and that the bodies were discovered under the floorings;—all points of dissimilarity to those of the Sarde buildings. The interpretation of the name as connected with fire, to which the word Nor-aghe is also said to refer, is the only coincidence of any importance. The points of positive dissimilarity are, that independently of being only from eight to fifteen feet in diameter, they are from 70 feet to 130 high; that they have a circular projecting base with a plinth, the stones are elaborately cut, joined with, though sometimes without, cement; and that, though closely fitting to each other, they are not in regular horizontal layers. The door is from six to fifteen feet above the ground, varies in position, is broad at base, narrow at top, or semicircular or lancet arched; and is usually ornamented with bands on the external face of the architrave; there is no spiral ramp or ascent; each floor is lighted by a window, and the upper story by four or six windows, facing the cardinal points; sculpture is found in parts, and also ornaments, as chevron work over the doorways; and, in regard to position, they are almost always found near churches.

The Boens in Kerry have a certain affinity, but too remote to assist us.

The tumulus of New Grange, on the banks of the Boyne, between Drogheda and Slane, County Meath, should not be left unmentioned. It was discovered in 1699 under a mound covering nearly two acres in extent, and made of stone, with a slight coating of earth. A long, narrow passage, not more than one foot six inches high and two feet broad, led to a chamber,—thus described by Mr. Petrie:--

“It is about twenty-two feet in diameter, covered with a dome of a bee-hive form, constructed of massive stones laid horizontally, and projecting one beyond the other till they approximate, and are finally capped with a single one; the height of the dome is about twenty feet, the chamber has three quadrangular recesses forming a cross, one facing the entrance gallery and one on each side. In each of these recesses is placed a stone urn or sarcophagus, of a simple bowl form, two of which remain. Of these recesses, the east and west are about eight feet square, the north is somewhat deeper. The entire length of the cavern, from the entrance of the gallery to the end of the recess, is eighty-one feet eight inches.” The building has various marks of sculpture—some of even refined workmanship—but none of the Ogham character.

No notice need be made of the numberless cromlechs in Ireland, beyond their existence and disconnection with the Round Towers; nor of the many relics discovered and attributed to a Phoenician origin.

The Scottish Dunes are circular towers, but the internal arrangements are entirely different; and their comparatively modern date and purposes are generally conceded.

The Dune of Dornadilla, in the parish of Duirnes, on Lord Reay’s estate at Strathmore, at first presents a Noraghic appearance; but the description by the Rev. Alexander Pope, in a letter to George Peton, dispels the expected similitude.