Sheik Sadiq Muhammad ibn Umayl

(Senior Zadith ben Hamuel)

c. 950 CE

trans. Jason Colavito

2018

|

NOTE |

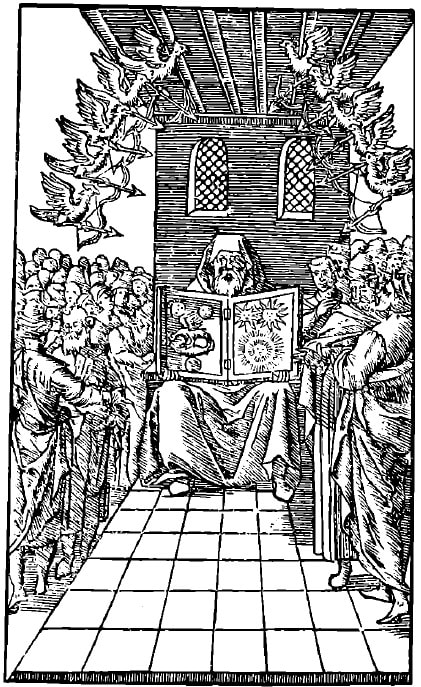

Sheik Sadiq Muhammad ibn Umayl (c. 900 - c. 960 CE) entered Latin literature from a garbling of his titles, becoming Senior Zadith ben Hamuel, and his prose commentary al-Mā’ al-Waraqî wa'l-Arḍ an-Najmīya (The Silvery Water and the Starry Earth) became a cornerstone of Western alchemy in Latin translation. Ibn Umayl lived in Egypt and explored alchemy, likely at Akhmim. He was heavily influenced by Zosimus of Panoplis and he was a follower of the Hermetic philosophy. In the introduction to his Silvery Water, Ibn Umayl describes a journey into an Egyptian temple near Memphis, apparently of the god-hero Imhotep, whose statues medieval alchemists mistook for those of Hermes due to their characteristic posture of a man holding an open book of wisdom. The translation below, made from the Latin translation of c. 1200 CE with notes about its departure from the Arabic, is based on the critical edition of the Latin text published by M. Turāb 'Alī in the Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 12, no. 1 (1933).

|

Senior Zadith, the son of Hamuel, said: Abū al-Qāsim and I entered a birba into a kind of subterranean house, and afterward al-Hasan and I saw all of the burned-out prisons of Joseph [sic for Arabic: “the prison of Joseph, known as Sidar Busir”]. I saw on the ceiling nine painted images of eagles, having their wings extended, as if they were flying, with their feet truly extended and open. In the feet of each eagle was a large bow, like those that archers are accustomed to carry. And on the walls of the house, to the right and the left as one enters, were images of standing men as perfect and beautiful as it is possible to be, dressed in clothes of different kinds and colors, having hands extended toward the interior of the innermost chamber, toward a certain statue seated in the house, on side of the door of the innermost chamber, to the left of the one who enters, facing him. It was seated on a chair similar to the chairs of the physicians, which could be separated from the statue. In its lap and held atop its forearms and its hands, which were extended over its lap, was a tablet of marble which could be separated from the statue. It had the length of one of the forearms [sic for Arabic “one cubit”] and the width of one of the palms [sic for Arabic “one span”], and the fingers of its hands were curled over the tablet from underneath, as if it were holding the tablet. And this tablet was like an open book to those entering, as though signaling the visitor to take a look at it. And in the part of the innermost chamber where it sat, there were infinite images of diverse things and letters in the barbarous tongue [Arabic: “in the letters of the birba,” i.e., hieroglyphics]. And the tablet which it had on its lap was divided in twain. There was a line which ran through the middle. On the lower part, tilted against the statue’s chest, there was the image of two birds, one having cut wings and the other two wings, and each having its tail in the beak of the other, as if the flying one wished to fly with the other, or the other wished to retain the flying one with him. These two birds, of the same type, were depicted together in a circle, as though to make the image of the Two-in-One, and next to the head of the flying bird of the two there was a circle. And above these two birds, near to the head of the tablet, nearest the fingers of the statue, there was the image of the crescent moon. And on the other part of the tablet there was another circle, looking at [sic for Arabic “similar to”] the birds below. There were always [sic for Arabic “in total”] five images, that is to say, the two birds and [the circle] below, and the moon and the other circle.

On the other half of the tablet, near the top part leaning against the fingers of the statue, there was an image of the sun emitting rays, making this image the “Two-in-One.” And in the other part there was another image of the sun, with only one ray descending. And this makes three, that is to say two lights, with two descending rays from one and one ray from the other, stretching to the bottom of the tablet, surrounded by a black circle divided in its circuit into two-thirds and one-third parts.

The third had the form of the crescent moon, and its interior parts were white without any blackness, and a black circle surrounded it and [apparent lacuna] a single sun, and its shape was as if the “Two-in-One.” And this is appearance of this half, which similarly had five images, and thus altogether there are ten, accordingly the number of those eagles and the black earth.

I have told you all of this and composed a poem about it, but we would not have any of it if not by the grace of God, whose name should be praised. So that you will understand it well and ponder it, in this poem I have depicted for you every image on this tablet, and the other images and figures which were in this place, and you will be able to weigh the significance of these figures in its chapters.

I have explicated and even explained these ten figures, and afterward I have demonstrated at the ends of my poem, which plainly was not able to be accomplished without poetry, and manifestly I have opened to you that which the wise man had hidden, the one who made the statue in this house, as if in his own image, in which he described the totality of his knowledge, and taught his wisdom through his stone and made it manifest to the perceptive.

I know that this statue is in the shape of the wise man, and that which is on the tablet which sits atop its forearms and knees on its lap is his hidden knowledge, which he described through the figures, that he might direct to them those who will have learned and understood nearer to what the wise man wanted to say through them. For by accurately and inwardly perceiving and recognizing the ends of wisdom, from discussions figurative and obscure, brought together with discussions of those images and figures, one can open the rest, nor will obscurity reign over the stone [sic for Arabic: “nor will it remain hidden from a possessor of wisdom.”].

On the other half of the tablet, near the top part leaning against the fingers of the statue, there was an image of the sun emitting rays, making this image the “Two-in-One.” And in the other part there was another image of the sun, with only one ray descending. And this makes three, that is to say two lights, with two descending rays from one and one ray from the other, stretching to the bottom of the tablet, surrounded by a black circle divided in its circuit into two-thirds and one-third parts.

The third had the form of the crescent moon, and its interior parts were white without any blackness, and a black circle surrounded it and [apparent lacuna] a single sun, and its shape was as if the “Two-in-One.” And this is appearance of this half, which similarly had five images, and thus altogether there are ten, accordingly the number of those eagles and the black earth.

I have told you all of this and composed a poem about it, but we would not have any of it if not by the grace of God, whose name should be praised. So that you will understand it well and ponder it, in this poem I have depicted for you every image on this tablet, and the other images and figures which were in this place, and you will be able to weigh the significance of these figures in its chapters.

I have explicated and even explained these ten figures, and afterward I have demonstrated at the ends of my poem, which plainly was not able to be accomplished without poetry, and manifestly I have opened to you that which the wise man had hidden, the one who made the statue in this house, as if in his own image, in which he described the totality of his knowledge, and taught his wisdom through his stone and made it manifest to the perceptive.

I know that this statue is in the shape of the wise man, and that which is on the tablet which sits atop its forearms and knees on its lap is his hidden knowledge, which he described through the figures, that he might direct to them those who will have learned and understood nearer to what the wise man wanted to say through them. For by accurately and inwardly perceiving and recognizing the ends of wisdom, from discussions figurative and obscure, brought together with discussions of those images and figures, one can open the rest, nor will obscurity reign over the stone [sic for Arabic: “nor will it remain hidden from a possessor of wisdom.”].