John Patterson MacLean

1878/1880

|

Georges Cuvier was one of the first to propose that Classical and medieval references to the discovery of giants' bones were mistaken identifications of the fossils of extinct elephants and other prehistoric mammals. Later writers expanded on his insight, offering new and interesting details about the fossil origins of fabulous beings from myth and legend.

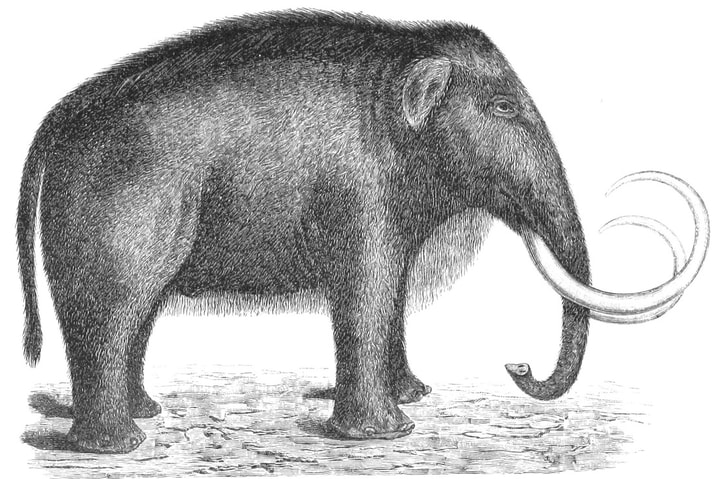

The following discussion comes from the 1880 second edition of John Patterson MacLean's Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man (1878), a brief tract that ran for three editions and attempted to summarize what was known of these prehistoric creatures and demonstrate that they lived contemporary with humankind. |

In nearly all ages and countries chance discoveries have been made of fossil bones of the elephant. That all these are to be ascribed to the mammoth is improbable, but many of them doubtless belonged to that animal. Fossil ivory was discovered in the soil of Greece as early as 320 B. C. The fossil bones of the elephant family when first discovered were ascribed either to human beings or else the demi-gods. The patella of a fossil elephant found in Greece was taken for the knee-bone of Ajax; the remains, thirteen feet in length, discovered by the Spartans at Tegea, were assigned to the body of Orestes; those, eighteen feet in length, discovered in the Isle of Ladea, were assigned to Asterius, son of Ajax; the bones discovered in the fourth century at Trapani, in Sicily, were ascribed to the pretended body of Polyphemus. So numerous were the discoveries, and so universally regarded to be those of human beings, that the literature of the middle ages, on this subject, is quite voluminous, and has been entitled "Gigantology."

In 1456, in France, bones of pretended giants were noticed in the bed of the Rhone. Soon after other discoveries were made near Saint-Peirat, opposite Valence, which were cared for by the Dauphin, afterwards Louis XI, and sent to Bourges, where they long remained objects of curiosity in the interior of the Saint-Chapelle. In the same neighborhood, in 1564, two peasants noticed, on the banks of the Rhone, some great bones sticking out of the ground. Cassanion pronounced them giants' bones, and this discovery doubtless caused him to write his treatise entitled “DeGigantibus.”

In the Canton of Lucerne, Switzerland, in the year 1577, a storm uprooted an oak near the cloisters of Reyden, exposing some large bones. These bones were examined by Felix Platen, then a celebrated physician and professor at Basle, who declared them to be the remains of a giant nineteen feet in height. On account of the conclusions of Platen the inhabitants of Lucerne adopted the image of the fabulous giant as the supporter of the city arms. In 1706 only two fragments of the skeleton remained, which, on being examined, by Blumenbach, were recognized as belonging to the elephant.

Otto de Guericke, a celebrated physicist and inventor of the air pump, in 1663, witnessed the discovery of the bones of the elephant, along with its enormous tusks, buried in the shelly-limestone, Germany. The tusks were taken for horns, and out of the remains Leibnitz constructed a strange animal, carrying a horn in the middle of its forehead, and in each jaw a dozen molar-teeth a foot long, and calling the creature the fossil unicorn. In his "Protogaea" he gave a description and a drawing of the imaginary animal. For more than thirty years the unicorn of Leibnitz was universally accepted throughout Germany, and was only dissipated by the discovery of an entire skeleton of the mammoth in the valley of the Unstrut.

Isbrant Ides, an intrepid Russian traveler, explored the principal regions of Northern Asia, and in 1692 reported that "amongst the hills, which are situated north-east of the river Kata, the mammuts' tongues and legs are found, as they are also particularly on the shores of the river Jenize, Trugan, Mongamsea, Lena, and near Jakutskoi, even as far as the Frozen Ocean. In the spring, when the ice of this river breaks, it is driven in such vast quantities and with such force by the high swollen waters, that it frequently carries very high banks before it, and breaks off the tops of hills, which, falling down, discover these animals whole, or their teeth only, almost frozen to the earth, which thaw by degrees. I had a person with me who had annually gone out in search of these bones; he told it to me as a real truth, that he and his companions found the head of one of these animals, which was discovered by the fall of such a frozen piece of earth. As soon as he opened it, he found the greatest part of the flesh rotten, but it was not without difficulty that they broke out his teeth, which were placed in the fore-part of his mouth, as those of the elephants are; they also took some bones out of his head, and afterwards came to the forefoot, which they cut off, and carried part of it to the city of Trugan, the circumference of it being as large as that of the waist of an ordinary man. The bones of the head appeared somewhat red, as though they were tinctured with blood."

This traveler further informs us that the old Siberian Russians affirmed "that there were elephants in this country before the Deluge, when this climate was warmer, and that their drowned bodies, floating on the surface of the water of that flood, were at last washed and forced into subterranean cavities; but that after this universal deluge, the air, which before was warm, was changed to cold, and that these bones have lain frozen in the earth ever since, and so are preserved from putrefaction till they thaw, and come to light, which is no very unreasonable conjecture, though it is not absolutely necessary that this climate should have been warmer before the Flood, since the carcases of the drowned elephants were very likely to float from other places several hundred miles distant to this country in the great deluge which covered the surface of the whole earth."

A veritable cemetery of elephants' bones was discovered, in 1700, by a soldier of Wurtemberg, in which were not less than sixty tusks in the argillaceous soil near the city of Canstadt. The bones which were entire were preserved, but the fragments were given to the court physician, by whom they were used to combat fever and colic.

About the year 1772, Pallas traveled through Siberia and described the bones of the mammoth as occurring in a very fresh state throughout all the Lowland of Siberia. He found their bones imbedded with marine remains and fossil wood or lignite, such as, he says, might have been derived from carbonized peat.

The Church at Valence, Spain, possessed the molar tooth of an elephant which was ascribed to St. Christopher, who, by the way, only existed in legendary tales; and in 1789 an elephant's femur was carried through the streets in public procession to procure rain, by the canons of St. Vincent, who pretended it was the arm of a Saint.

During the eighteenth century the discoveries were very numerous, and the erudition of that time easily unraveled the mystery. But as science has been forced to contest its way step by step, so even then a check to her progress was attempted. Some wiseacre declared that the bones found in France and Italy, were the remains of the elephants which Hannibal had brought from Carthage in his expedition against Rome. Many thought this view was very plausible, from the fact that these bones were numerously found along the route of the Carthagenian army. But as' these bones are found where no Carthagenian ever trod, or any army with elephants in its train, the fact no longer becomes plausible. Even if the remains of elephants were only found along the route of Hannibal, their position in the earth, as well as their distinct variety, would preclude the idea that they came from Africa with the Carthagenians.

In 1456, in France, bones of pretended giants were noticed in the bed of the Rhone. Soon after other discoveries were made near Saint-Peirat, opposite Valence, which were cared for by the Dauphin, afterwards Louis XI, and sent to Bourges, where they long remained objects of curiosity in the interior of the Saint-Chapelle. In the same neighborhood, in 1564, two peasants noticed, on the banks of the Rhone, some great bones sticking out of the ground. Cassanion pronounced them giants' bones, and this discovery doubtless caused him to write his treatise entitled “DeGigantibus.”

In the Canton of Lucerne, Switzerland, in the year 1577, a storm uprooted an oak near the cloisters of Reyden, exposing some large bones. These bones were examined by Felix Platen, then a celebrated physician and professor at Basle, who declared them to be the remains of a giant nineteen feet in height. On account of the conclusions of Platen the inhabitants of Lucerne adopted the image of the fabulous giant as the supporter of the city arms. In 1706 only two fragments of the skeleton remained, which, on being examined, by Blumenbach, were recognized as belonging to the elephant.

Otto de Guericke, a celebrated physicist and inventor of the air pump, in 1663, witnessed the discovery of the bones of the elephant, along with its enormous tusks, buried in the shelly-limestone, Germany. The tusks were taken for horns, and out of the remains Leibnitz constructed a strange animal, carrying a horn in the middle of its forehead, and in each jaw a dozen molar-teeth a foot long, and calling the creature the fossil unicorn. In his "Protogaea" he gave a description and a drawing of the imaginary animal. For more than thirty years the unicorn of Leibnitz was universally accepted throughout Germany, and was only dissipated by the discovery of an entire skeleton of the mammoth in the valley of the Unstrut.

Isbrant Ides, an intrepid Russian traveler, explored the principal regions of Northern Asia, and in 1692 reported that "amongst the hills, which are situated north-east of the river Kata, the mammuts' tongues and legs are found, as they are also particularly on the shores of the river Jenize, Trugan, Mongamsea, Lena, and near Jakutskoi, even as far as the Frozen Ocean. In the spring, when the ice of this river breaks, it is driven in such vast quantities and with such force by the high swollen waters, that it frequently carries very high banks before it, and breaks off the tops of hills, which, falling down, discover these animals whole, or their teeth only, almost frozen to the earth, which thaw by degrees. I had a person with me who had annually gone out in search of these bones; he told it to me as a real truth, that he and his companions found the head of one of these animals, which was discovered by the fall of such a frozen piece of earth. As soon as he opened it, he found the greatest part of the flesh rotten, but it was not without difficulty that they broke out his teeth, which were placed in the fore-part of his mouth, as those of the elephants are; they also took some bones out of his head, and afterwards came to the forefoot, which they cut off, and carried part of it to the city of Trugan, the circumference of it being as large as that of the waist of an ordinary man. The bones of the head appeared somewhat red, as though they were tinctured with blood."

This traveler further informs us that the old Siberian Russians affirmed "that there were elephants in this country before the Deluge, when this climate was warmer, and that their drowned bodies, floating on the surface of the water of that flood, were at last washed and forced into subterranean cavities; but that after this universal deluge, the air, which before was warm, was changed to cold, and that these bones have lain frozen in the earth ever since, and so are preserved from putrefaction till they thaw, and come to light, which is no very unreasonable conjecture, though it is not absolutely necessary that this climate should have been warmer before the Flood, since the carcases of the drowned elephants were very likely to float from other places several hundred miles distant to this country in the great deluge which covered the surface of the whole earth."

A veritable cemetery of elephants' bones was discovered, in 1700, by a soldier of Wurtemberg, in which were not less than sixty tusks in the argillaceous soil near the city of Canstadt. The bones which were entire were preserved, but the fragments were given to the court physician, by whom they were used to combat fever and colic.

About the year 1772, Pallas traveled through Siberia and described the bones of the mammoth as occurring in a very fresh state throughout all the Lowland of Siberia. He found their bones imbedded with marine remains and fossil wood or lignite, such as, he says, might have been derived from carbonized peat.

The Church at Valence, Spain, possessed the molar tooth of an elephant which was ascribed to St. Christopher, who, by the way, only existed in legendary tales; and in 1789 an elephant's femur was carried through the streets in public procession to procure rain, by the canons of St. Vincent, who pretended it was the arm of a Saint.

During the eighteenth century the discoveries were very numerous, and the erudition of that time easily unraveled the mystery. But as science has been forced to contest its way step by step, so even then a check to her progress was attempted. Some wiseacre declared that the bones found in France and Italy, were the remains of the elephants which Hannibal had brought from Carthage in his expedition against Rome. Many thought this view was very plausible, from the fact that these bones were numerously found along the route of the Carthagenian army. But as' these bones are found where no Carthagenian ever trod, or any army with elephants in its train, the fact no longer becomes plausible. Even if the remains of elephants were only found along the route of Hannibal, their position in the earth, as well as their distinct variety, would preclude the idea that they came from Africa with the Carthagenians.