Out of Place Artifacts, or OOPARTS, have become a touchstone of creationist, lost civilization, and alternative history theorists, who see in hazy accounts of supposedly impossible technology and seemingly human artifacts in impossibly old geologic strata proof that modern science is wrong. Authors like Cremo and Thompson, writing in Forbidden Archaeology (1993), rarely provide the full original texts that support such assertions. Below are original texts that report high technology and impossible artifacts. They should be taken with a grain of salt. Most are not what they seem.

Archimedes' Death Ray

Galen, De temperamentis 3.2 (1st century CE)

It is in this way, at least I think so, that Archimedes burnt the enemy's vessels. For, by the help of a burning mirror, he may easily set fire to wool, hemp, wood, &c.; and, in short, to any thing dry and light.

John Zonaras, Epitome ton Istorion 9.4 (12th century CE)

Archimedes burnt the fleet of the Romans in an admirable manner; for he turned a certain mirror towards the sun, and which received its rays. The air having been heated on account of the density and smoothness of this mirror, he kindled an immense flame, which he precipitated on the vessels which were in the harbour and reduced them to ashes.

John Tzetzes, Chiliades 12 (12th century CE)

When the fleet of Marcellus was within bow-shot, the old man (Archimedes) brought out a hexagonal mirror which he had made. He placed at proper distances from this mirror other smaller mirrors which were of the same kind, and which were moved by means of their hinges and certain square plates of metal. He afterwards placed his mirror in the midst of the solar rays, precisely at noon day. The rays of the sun being reflected by this mirror, he kindled a dreadful fire in the ships, which were reduced to ashes at a distance equal to that of a bowshot. [...] Dion and Diodorus, who wrote the life of Archimedes, and several other authors, speak of this fact; but chiefly Anthemius, who wrote on the prodigies of mechanics; Hero, Philo, Pappus, and in short all'who have written on ancient mechanics: it is in these works that we read the history of the conflagration occasioned by the mirror of Archimedes.

Translated anonymously in 1811 by the Philosophical Magazine.

It is in this way, at least I think so, that Archimedes burnt the enemy's vessels. For, by the help of a burning mirror, he may easily set fire to wool, hemp, wood, &c.; and, in short, to any thing dry and light.

John Zonaras, Epitome ton Istorion 9.4 (12th century CE)

Archimedes burnt the fleet of the Romans in an admirable manner; for he turned a certain mirror towards the sun, and which received its rays. The air having been heated on account of the density and smoothness of this mirror, he kindled an immense flame, which he precipitated on the vessels which were in the harbour and reduced them to ashes.

John Tzetzes, Chiliades 12 (12th century CE)

When the fleet of Marcellus was within bow-shot, the old man (Archimedes) brought out a hexagonal mirror which he had made. He placed at proper distances from this mirror other smaller mirrors which were of the same kind, and which were moved by means of their hinges and certain square plates of metal. He afterwards placed his mirror in the midst of the solar rays, precisely at noon day. The rays of the sun being reflected by this mirror, he kindled a dreadful fire in the ships, which were reduced to ashes at a distance equal to that of a bowshot. [...] Dion and Diodorus, who wrote the life of Archimedes, and several other authors, speak of this fact; but chiefly Anthemius, who wrote on the prodigies of mechanics; Hero, Philo, Pappus, and in short all'who have written on ancient mechanics: it is in these works that we read the history of the conflagration occasioned by the mirror of Archimedes.

Translated anonymously in 1811 by the Philosophical Magazine.

Ancient Astronomical Computer

Cicero, De re publica 1.14 (1st century BCE)

But as soon as Gallus had begun to explain, in a most scientific manner, the principle of this [Archimedes’] machine, I felt that the Sicilian geometrician must have possessed a genius superior to anything we usually conceive to belong to our nature. For Gallus assured us that that other solid and compact globe was a very ancient invention, and that the first model had been originally made by Thales of Miletus. That afterward Eudoxus of Cnidus, a disciple of Plato, had traced on its surface the stars that appear in the sky, and that many years subsequently, borrowing from Eudoxus this beautiful design and representation, Aratus had illustrated it in his verses, not by any science of astronomy, but by the ornament of poetic description. He added that the figure of the globe, which displayed the motions of the sun and moon, and the five planets, or wandering stars, could not be represented by the primitive solid globe; and that in this the invention of Archimedes was admirable, because he had calculated how a single revolution should maintain unequal and diversified progressions in dissimilar motions. In fact, when Gallus moved this globe, we observed that the moon succeeded the sun by as many turns of the wheel in the machine as days in the heavens. From whence it resulted that the progress of the sun was marked as in the heavens, and that the moon touched the point where she is obscured by the earth’s shadow at the instant the sun appears opposite… [text breaks off]

Translated by C. D. Yonge.

But as soon as Gallus had begun to explain, in a most scientific manner, the principle of this [Archimedes’] machine, I felt that the Sicilian geometrician must have possessed a genius superior to anything we usually conceive to belong to our nature. For Gallus assured us that that other solid and compact globe was a very ancient invention, and that the first model had been originally made by Thales of Miletus. That afterward Eudoxus of Cnidus, a disciple of Plato, had traced on its surface the stars that appear in the sky, and that many years subsequently, borrowing from Eudoxus this beautiful design and representation, Aratus had illustrated it in his verses, not by any science of astronomy, but by the ornament of poetic description. He added that the figure of the globe, which displayed the motions of the sun and moon, and the five planets, or wandering stars, could not be represented by the primitive solid globe; and that in this the invention of Archimedes was admirable, because he had calculated how a single revolution should maintain unequal and diversified progressions in dissimilar motions. In fact, when Gallus moved this globe, we observed that the moon succeeded the sun by as many turns of the wheel in the machine as days in the heavens. From whence it resulted that the progress of the sun was marked as in the heavens, and that the moon touched the point where she is obscured by the earth’s shadow at the instant the sun appears opposite… [text breaks off]

Translated by C. D. Yonge.

Flexible Glass (Vitrum Flexile)

Petronius, Satyricon 51 (c. 60 CE)

"But there was an artisan, once upon a time, who made a glass vial that couldn't be broken. On that account he was admitted to Caesar with his gift; then he dashed it upon the floor, when Caesar handed it back to him. The Emperor was greatly startled, but the artisan picked the vial up off the pavement, and it was dented, just like a brass bowl would have been! He took a little hammer out of his tunic and beat out the dent without any trouble. When he had done that, he thought he would soon be in Jupiter's heaven, and more especially when Caesar said to him, 'Is there anyone else who knows how to make this malleable glass? Think now!' And when he denied that anyone else knew the secret, Caesar ordered his head chopped off, because if this should get out, we would think no more of gold than we would of dirt."

Translated by W. C. Firebaught.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History 36.66 (1st century CE)

In the reign of Tiberius, it is said, a combination was devised which produced a flexible glass; but the manufactory of the artist was totally destroyed, we are told, in order to prevent the value of copper, silver, and gold, from becoming depreciated. This story, however, was, for a long time, more widely spread than well authenticated.

Translated by John Bostock and H. T. Riley.

Cassius Dio, Roman History 57.21 (c. 200 CE)

At the time Tiberius both admired and envied him [an architect who saved a portico]; for the former reason he honoured him with a present of money, and for the latter he expelled him from the city. Later the exile approached him to crave pardon, and while doing so purposely let fall a crystal goblet; and though it was bruised in some way or shattered, yet by passing his hands over it he promptly exhibited it whole once more. For this he hoped to obtain pardon, but instead the emperor put him to death.

Translated by Earnest Cary.

"But there was an artisan, once upon a time, who made a glass vial that couldn't be broken. On that account he was admitted to Caesar with his gift; then he dashed it upon the floor, when Caesar handed it back to him. The Emperor was greatly startled, but the artisan picked the vial up off the pavement, and it was dented, just like a brass bowl would have been! He took a little hammer out of his tunic and beat out the dent without any trouble. When he had done that, he thought he would soon be in Jupiter's heaven, and more especially when Caesar said to him, 'Is there anyone else who knows how to make this malleable glass? Think now!' And when he denied that anyone else knew the secret, Caesar ordered his head chopped off, because if this should get out, we would think no more of gold than we would of dirt."

Translated by W. C. Firebaught.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History 36.66 (1st century CE)

In the reign of Tiberius, it is said, a combination was devised which produced a flexible glass; but the manufactory of the artist was totally destroyed, we are told, in order to prevent the value of copper, silver, and gold, from becoming depreciated. This story, however, was, for a long time, more widely spread than well authenticated.

Translated by John Bostock and H. T. Riley.

Cassius Dio, Roman History 57.21 (c. 200 CE)

At the time Tiberius both admired and envied him [an architect who saved a portico]; for the former reason he honoured him with a present of money, and for the latter he expelled him from the city. Later the exile approached him to crave pardon, and while doing so purposely let fall a crystal goblet; and though it was bruised in some way or shattered, yet by passing his hands over it he promptly exhibited it whole once more. For this he hoped to obtain pardon, but instead the emperor put him to death.

Translated by Earnest Cary.

An Ancient Egyptian iPad

Al-Maqrizi, Al Khitat (c. 1400)

After him [Shahlûk] reigned his son Surid. He was an excellently wise man; and he was the first who levied taxes in Egypt, and the first who ordered an expenditure from his treasuries for the sick and the palsied, and the first who instituted the observation (?) of daybreak. He made wonderful things; among which was a mirror of mixed metal, in which he would observe the countries, and know in it the occurrences that happened, and what was abundant in them, and what was scarce. He placed this mirror in the midst of the city of Amsûs [the antediluvian capital of Egypt], and it was of copper. He made also in Amsûs the image of a sitting female nursing a child in her lap. … That image remained until the Flood destroyed it; but in the books of the Copts [it is said] that it was found after the Flood, and that the greater part of the people worshipped it.

Anonymous 1859 translation in the London Quarterly.

After him [Shahlûk] reigned his son Surid. He was an excellently wise man; and he was the first who levied taxes in Egypt, and the first who ordered an expenditure from his treasuries for the sick and the palsied, and the first who instituted the observation (?) of daybreak. He made wonderful things; among which was a mirror of mixed metal, in which he would observe the countries, and know in it the occurrences that happened, and what was abundant in them, and what was scarce. He placed this mirror in the midst of the city of Amsûs [the antediluvian capital of Egypt], and it was of copper. He made also in Amsûs the image of a sitting female nursing a child in her lap. … That image remained until the Flood destroyed it; but in the books of the Copts [it is said] that it was found after the Flood, and that the greater part of the people worshipped it.

Anonymous 1859 translation in the London Quarterly.

A Roman Coin in Ancient Panama

Lucio Marineo Siculo, De rebus Hispaniae memorabilibus 19 (1533)

Yet there is one thing in this place that I shall not pass over in silence because it is most remarkable and most worthy to be known, especially since others, so far as I have observed, have omitted it in their writings. In a certain region, which is said to be on the mainland [near Darien], whose bishop was Juan de Quevedo, of the Minor Order [a Franciscan], there was discovered by men digging in the earth searching for gold a coin with the name and image of Caesar Augustus. Juan Rufo, archbishop of Consencia, obtaining this, sent it to Rome, to the Supreme Pontiff, as a remarkable object. This wonderful thing has ripped the glory from the sailors of our time, who once boasted that they had sailed there before all others, since the evidence of this coin now makes certain that the Romans once reached the Indies.

Translated by Jason Colavito.

Yet there is one thing in this place that I shall not pass over in silence because it is most remarkable and most worthy to be known, especially since others, so far as I have observed, have omitted it in their writings. In a certain region, which is said to be on the mainland [near Darien], whose bishop was Juan de Quevedo, of the Minor Order [a Franciscan], there was discovered by men digging in the earth searching for gold a coin with the name and image of Caesar Augustus. Juan Rufo, archbishop of Consencia, obtaining this, sent it to Rome, to the Supreme Pontiff, as a remarkable object. This wonderful thing has ripped the glory from the sailors of our time, who once boasted that they had sailed there before all others, since the evidence of this coin now makes certain that the Romans once reached the Indies.

Translated by Jason Colavito.

Manned Flight in Moorish Spain

Al-Maqqari, Breath of Perfume 2.3 (1629)

Abú-l-’abbás Kasim Ibn Firnas, the physician, was the first who made glass out of clay, and who established fabrics of it in Andalus. He passes also as the first man who introduced into that country the famous treatise on prosody by Khalil, and who taught the science of music. He invented an instrument called al-minkdlah, by means of which time was marked in music without having recourse to notes or figures. Among other very curious experiments which he made, one is his trying to fly. He covered himself with feathers for the purpose, attached a couple of wings to his body, and, getting on an eminence, flung himself down into the air, when, according to the testimony of several trustworthy writers who witnessed the performance, he flew to a considerable distance, as if he had been a bird, but in alighting again on the place whence he had started his back was very much hurt, for not knowing that birds when they alight come down upon their tails, he forgot to provide himself with one. Múmen Ibn Sa'id has said, in a verse alluding to this extraordinary man,--

"He surpassed in velocity the flight of the ostrich, but he neglected to arm his body with the strength of the vulture."

The same poet has said in allusion to a certain figure of heaven which this Ibn Firnas, who was likewise a consummate astronomer, made in his house, and where the spectators fancied they saw the clouds, the stars, and the lightning, and listened to the terrific noise of thunder,--

"The heavens of Abú-l-kásim 'Abbás, the learned, will deeply impress on thy mind the extent of their perfection and beauty.

"Thou shalt hear the thunder roar, lightning will cross thy sight: nay, by Allah! the very firmament will shake to its foundations.

"But do not go underneath (the house), lest thou shouldst feel inclined, as I was, (seeing the deception,) to spit in the face of its creator."

The following verse is the composition of Ibn Firnas himself, who addressed it to the Amir Mohammed.

"I saw the Prince of the believers, Mohammed, and the flourishing star of benevolence shone bright upon his countenance."

To which Mumen replied, when he was told of it, "Yes, thou art right, but it vanished the very moment thou didst come near it; thou hast made the face of the Khalif a field where the stars flourish; ay, and a dung-hill too, for plants do not thrive without manure."

Translated by Pascual de Gayangos.

Abú-l-’abbás Kasim Ibn Firnas, the physician, was the first who made glass out of clay, and who established fabrics of it in Andalus. He passes also as the first man who introduced into that country the famous treatise on prosody by Khalil, and who taught the science of music. He invented an instrument called al-minkdlah, by means of which time was marked in music without having recourse to notes or figures. Among other very curious experiments which he made, one is his trying to fly. He covered himself with feathers for the purpose, attached a couple of wings to his body, and, getting on an eminence, flung himself down into the air, when, according to the testimony of several trustworthy writers who witnessed the performance, he flew to a considerable distance, as if he had been a bird, but in alighting again on the place whence he had started his back was very much hurt, for not knowing that birds when they alight come down upon their tails, he forgot to provide himself with one. Múmen Ibn Sa'id has said, in a verse alluding to this extraordinary man,--

"He surpassed in velocity the flight of the ostrich, but he neglected to arm his body with the strength of the vulture."

The same poet has said in allusion to a certain figure of heaven which this Ibn Firnas, who was likewise a consummate astronomer, made in his house, and where the spectators fancied they saw the clouds, the stars, and the lightning, and listened to the terrific noise of thunder,--

"The heavens of Abú-l-kásim 'Abbás, the learned, will deeply impress on thy mind the extent of their perfection and beauty.

"Thou shalt hear the thunder roar, lightning will cross thy sight: nay, by Allah! the very firmament will shake to its foundations.

"But do not go underneath (the house), lest thou shouldst feel inclined, as I was, (seeing the deception,) to spit in the face of its creator."

The following verse is the composition of Ibn Firnas himself, who addressed it to the Amir Mohammed.

"I saw the Prince of the believers, Mohammed, and the flourishing star of benevolence shone bright upon his countenance."

To which Mumen replied, when he was told of it, "Yes, thou art right, but it vanished the very moment thou didst come near it; thou hast made the face of the Khalif a field where the stars flourish; ay, and a dung-hill too, for plants do not thrive without manure."

Translated by Pascual de Gayangos.

A Prehuman Quarry in France

American Journal of Science, vol. 2, no. 1 (April 1820)

This commonly reprinted piece quotes in highly abbreviated form, a passage from the Comte de Bournon’s 1808 Traité de minéralogie, which in turn is quoting and commenting on a letter of Mr. le Chevalier de Sade (Louis de Sade), recalling a memory from twenty years earlier.

During the years 1786, 7, and 8, they were occupied near Aix in Provence, in France, in quarrying stone for the rebuilding, upon a vast scale, of the Palace of Justice. The stone was a limestone of a deep grey, and of that kind which are tender when they come out of the quarry, but harden by exposure to the air. The strata were separated from one another by a bed of sand mixed with clay, more or less calcareous. The first which were wrought presented no appearance of any foreign bodies, but, after the workmen had removed the ten first beds, they were astonished, when taking away the eleventh, to find its inferior surface, at the depth of forty or fifty feet, covered with shells. The stone of this bed having been removed, as they were taking away a stratum of argillaceous sand, which separated the eleventh bed from the twelfth, they found stumps of columns and fragments of stones half wrought, and the stone was exactly similar to that of the quarry: they found moreover coins, handles of hammers, and other tools or fragments of tools in wood. But that which principally commanded their attention, was a board about one inch thick and seven or eight feet long; it was broken into many pieces, of which none were missing, and it was possible to join them again one to another, and to restore to the board or plate its original form, which was that of the boards of the same kind used by the masons and quarry men: it was worn in the same manner, rounded and waving upon the edges. The stones which were completely or partly wrought, had not at all changed in their nature, but the fragments of the board, and the instruments, and pieces of instruments of wood, had been changed into agate, which was very fine and agreeably coloured.

Here then, (observes Count Bournon,) we have the traces of a work executed by the hand of man, placed at the depth of fifty feet, and covered with eleven beds of compact limestone: every thing tended to prove that this work had been executed upon the spot where the traces existed. The presence of man had then preceded the formation of this stone, and that very considerably since he was already arrived at such a degree of civilization that the arts were known to him, and that he wrought the stone and formed columns out of it.

Here is the same passage with all of the omissions and quotation marks restored, and mistranslations corrected:

“During the years 1786, 87, and 88, they were occupied near Aix in Provence on the rebuilding of the Palace of Justice upon a vast plan, which plan was given by Mr. le Doux [Claude-Nicolas Ledoux], the King’s Architect. The cut stone which served this construction was taken from the quarry of St. Eutrope, located on a small hill about a mile from the town, and very near the Convent of the Trinity. The stone which formed this hill, where it was arranged in layers, was limestone of a deep grey, and of that kind which is tender when it comes out of the quarry, but hardens by exposure to the air. The strata were separated from one another by a bed of sand mixed with clay, more or less calcareous. The first which were wrought presented no appearance of any fossils, but, after the workmen had removed the ten first beds, they were astonished, when taking away the eleventh, to find its inferior surface, at the depth of 40 or 50 feet, covered with shells. The stone of this bed having been removed, as they were taking away a stratum of argillaceous sand, which separated the eleventh bed from the twelfth, they found stumps of columns and fragments of stones half wrought, and the stone was exactly similar to that of the layers to which they belonged: they found moreover wedges, handles of hammers, and other tools or fragments of wooden tools. But that which principally commanded their attention, was a board about one inch thick and seven or 7 or 8 feet long; it was broken into many pieces, of which none were missing, and it was possible to join them again one to another, and to restore to the board its original form, which was that of the boards of the same kind used by the masons and quarry men: it was worn in the same manner, rounded and waving upon the edges. Being then in Aix, I paid a visit to this quarry. The owner was kind enough to show me all of the pieces that had been found. The stones which were completely or partly wrought, had not at all changed in their nature, but the fragments of the board, and the instruments, and pieces of instruments of wood, had been changed into agate, which was very fine and agreeably colored. This discovery was made in the course of the year 1788, during the first uprisings, which began to manifest in Provence, halted the construction of the palace, and created an obstacle to continued observation.”

I copied the note of this fact as it was given to me by Mr. Chevalier de Sades, who gathered together the particulars, as much as his memory of 20 years ago was able to help him: It seemed to me to be too interesting to ignore. This is accompanied by good circumstances that attract curiosity and interest. This quite positively shows the traces of a work executed by the hand of man, placed at the depth of 50 feet, and covered with 11 beds of compact limestone: everything tended to prove that this work had been executed upon the spot where the traces existed. The presence of man had then preceded the formation of this stone, and that very considerably since he was already arrived at such a degree of civilization that the arts were known to him, and that he wrought the stone and formed columns out of it. On the other hand, Aix is in the center of a rather deep basin: the stone which formed near this city, the small elevation of St. Eutrope, seems to show no further trace of its existence in the area, even at a considerable distance from the town: it is therefore a local formation, isolated and specific, and is clearly also the product of different deposits, all of which were accompanied by a precipitation of sand and clay, which indicates the action of the current that at the same time had made the formation from this stone in a pool of water which necessarily occupied then the basin in which the city of Aix is today. However, this pool had to be dry at the time in which the stones were carved, just as it was when they were found. So a disaster must have introduced water into the basin, and the shells found on the underside of the single layer that covered the remains of human labor would seem to indicate that the sea had something to do with. This would not be surprising since Aix is only 6 or 7 leagues away (from the sea). The currents that later would be established in the higher elevations, heading toward the waters of the basin, would do the rest; and a new drying of the same basin would then return it to the state in which it appears in this time.

I feel that this explanation, given from nearly 300 leagues away from where the observation of the facts in question was made, and by a man who knows it only secondhand, cannot provide a full accounting of all of the circumstances surrounding this incident, nor the general topography of the place where the material was found. It cannot be regarded as more than a probability, to be used only to direct some of the research that could be made on this place into the real cause of such an interesting fact, and it will disappear in the face of any more likely or satisfactory explanation that can be given. The study is very easy, from the place itself, and perhaps some mineralogists and geologists are already busy there; but I repeat, the site seems to me isolated from the grand formation of the rocky structure of our globe, and has no connection with it.

This commonly reprinted piece quotes in highly abbreviated form, a passage from the Comte de Bournon’s 1808 Traité de minéralogie, which in turn is quoting and commenting on a letter of Mr. le Chevalier de Sade (Louis de Sade), recalling a memory from twenty years earlier.

During the years 1786, 7, and 8, they were occupied near Aix in Provence, in France, in quarrying stone for the rebuilding, upon a vast scale, of the Palace of Justice. The stone was a limestone of a deep grey, and of that kind which are tender when they come out of the quarry, but harden by exposure to the air. The strata were separated from one another by a bed of sand mixed with clay, more or less calcareous. The first which were wrought presented no appearance of any foreign bodies, but, after the workmen had removed the ten first beds, they were astonished, when taking away the eleventh, to find its inferior surface, at the depth of forty or fifty feet, covered with shells. The stone of this bed having been removed, as they were taking away a stratum of argillaceous sand, which separated the eleventh bed from the twelfth, they found stumps of columns and fragments of stones half wrought, and the stone was exactly similar to that of the quarry: they found moreover coins, handles of hammers, and other tools or fragments of tools in wood. But that which principally commanded their attention, was a board about one inch thick and seven or eight feet long; it was broken into many pieces, of which none were missing, and it was possible to join them again one to another, and to restore to the board or plate its original form, which was that of the boards of the same kind used by the masons and quarry men: it was worn in the same manner, rounded and waving upon the edges. The stones which were completely or partly wrought, had not at all changed in their nature, but the fragments of the board, and the instruments, and pieces of instruments of wood, had been changed into agate, which was very fine and agreeably coloured.

Here then, (observes Count Bournon,) we have the traces of a work executed by the hand of man, placed at the depth of fifty feet, and covered with eleven beds of compact limestone: every thing tended to prove that this work had been executed upon the spot where the traces existed. The presence of man had then preceded the formation of this stone, and that very considerably since he was already arrived at such a degree of civilization that the arts were known to him, and that he wrought the stone and formed columns out of it.

Here is the same passage with all of the omissions and quotation marks restored, and mistranslations corrected:

“During the years 1786, 87, and 88, they were occupied near Aix in Provence on the rebuilding of the Palace of Justice upon a vast plan, which plan was given by Mr. le Doux [Claude-Nicolas Ledoux], the King’s Architect. The cut stone which served this construction was taken from the quarry of St. Eutrope, located on a small hill about a mile from the town, and very near the Convent of the Trinity. The stone which formed this hill, where it was arranged in layers, was limestone of a deep grey, and of that kind which is tender when it comes out of the quarry, but hardens by exposure to the air. The strata were separated from one another by a bed of sand mixed with clay, more or less calcareous. The first which were wrought presented no appearance of any fossils, but, after the workmen had removed the ten first beds, they were astonished, when taking away the eleventh, to find its inferior surface, at the depth of 40 or 50 feet, covered with shells. The stone of this bed having been removed, as they were taking away a stratum of argillaceous sand, which separated the eleventh bed from the twelfth, they found stumps of columns and fragments of stones half wrought, and the stone was exactly similar to that of the layers to which they belonged: they found moreover wedges, handles of hammers, and other tools or fragments of wooden tools. But that which principally commanded their attention, was a board about one inch thick and seven or 7 or 8 feet long; it was broken into many pieces, of which none were missing, and it was possible to join them again one to another, and to restore to the board its original form, which was that of the boards of the same kind used by the masons and quarry men: it was worn in the same manner, rounded and waving upon the edges. Being then in Aix, I paid a visit to this quarry. The owner was kind enough to show me all of the pieces that had been found. The stones which were completely or partly wrought, had not at all changed in their nature, but the fragments of the board, and the instruments, and pieces of instruments of wood, had been changed into agate, which was very fine and agreeably colored. This discovery was made in the course of the year 1788, during the first uprisings, which began to manifest in Provence, halted the construction of the palace, and created an obstacle to continued observation.”

I copied the note of this fact as it was given to me by Mr. Chevalier de Sades, who gathered together the particulars, as much as his memory of 20 years ago was able to help him: It seemed to me to be too interesting to ignore. This is accompanied by good circumstances that attract curiosity and interest. This quite positively shows the traces of a work executed by the hand of man, placed at the depth of 50 feet, and covered with 11 beds of compact limestone: everything tended to prove that this work had been executed upon the spot where the traces existed. The presence of man had then preceded the formation of this stone, and that very considerably since he was already arrived at such a degree of civilization that the arts were known to him, and that he wrought the stone and formed columns out of it. On the other hand, Aix is in the center of a rather deep basin: the stone which formed near this city, the small elevation of St. Eutrope, seems to show no further trace of its existence in the area, even at a considerable distance from the town: it is therefore a local formation, isolated and specific, and is clearly also the product of different deposits, all of which were accompanied by a precipitation of sand and clay, which indicates the action of the current that at the same time had made the formation from this stone in a pool of water which necessarily occupied then the basin in which the city of Aix is today. However, this pool had to be dry at the time in which the stones were carved, just as it was when they were found. So a disaster must have introduced water into the basin, and the shells found on the underside of the single layer that covered the remains of human labor would seem to indicate that the sea had something to do with. This would not be surprising since Aix is only 6 or 7 leagues away (from the sea). The currents that later would be established in the higher elevations, heading toward the waters of the basin, would do the rest; and a new drying of the same basin would then return it to the state in which it appears in this time.

I feel that this explanation, given from nearly 300 leagues away from where the observation of the facts in question was made, and by a man who knows it only secondhand, cannot provide a full accounting of all of the circumstances surrounding this incident, nor the general topography of the place where the material was found. It cannot be regarded as more than a probability, to be used only to direct some of the research that could be made on this place into the real cause of such an interesting fact, and it will disappear in the face of any more likely or satisfactory explanation that can be given. The study is very easy, from the place itself, and perhaps some mineralogists and geologists are already busy there; but I repeat, the site seems to me isolated from the grand formation of the rocky structure of our globe, and has no connection with it.

A Strange Inscription in Eight Million Year Old Marble in Norristown, Penn.

The Register of Pennsylvania (April 1830)

CURIOSITY.

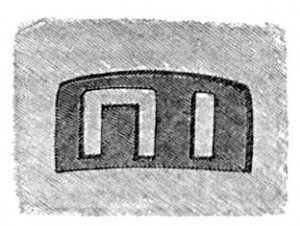

A solid block of white marble, of thirty cubic feet, was lately taken out of Henderson’s quarry, at the depth of seventy feet, four or five miles from Norristown, on the western side of the river Schuylkill. It was sent to Norristown, to be cut by the saw into slabs. One of these slabs presents to the eye a remarkable curiosity: On one of its sides are two characters, somewhat resembling the English word in, regularly cut into the marble. This singular appearance must either have been a freak of nature, or the work of man executed ages ago, and the marble must have been growing over it ever since; for it was found by the sawyer in the very interior of the block. The curious slab is now in possession of Col. Peter A. Browne, of this city, who will, we are sure, take pleasure in showing it to any gentleman who may be inquisitive on geological subjects.

Penn. Inquirer.

To the Editor of the Pennsylvania Inquirer. Sir—Observing that you have noticed, in your paper of Thursday last, the curious marble slab which I have in my possession, I will furnish you with some further particulars in relation to it. The block was taken out of Henderson's quarry, Upper Merion township, Montgomery county, Pennsylvania, between 60 and 70 feet below the surface of the earth; it measured upwards of SO cubic feet; it was purchased by Mr. Alexander Ramsey of Norristown, to whose liberality I am indebted for the slab, and was by him sent to Mr. Savage's marble saw mill to be cut. A slab two inches in thickness was taken off and displayed to view, nearly in the centre, an indentation 1J inch long by 5-8ths of an inch wide, handsomely arched above and rectangular below. In this cavity was a black powder, which being removed, TWO CHARACTERS were observed—These are raised, and are at equal distances from the top, bottom and sides of the indentation from each other. That the letters have not been put there since the block was cut, is proved by several gentlemen of Norristown of the highest respectability, who saw it soon after the sawing; and moreover, it is apparent to any person accustomed to examine mineral substances, that no tool whatever has been used; the surface of the indentation, as well as that of the letters, has a vitrified or semi-chrystallized appearance. Mr. Strickland and Mr. Peale, both of whom hate examined the slab carefully with a magnifying glass, agree with me in this particular. The marble belongs to the primitive limestone formation, which in this district is the last of the primitive scries, commencing at Philadelphia, and pursuing the following order: gneiss, mica-slate, hornblende, talcose slate, primitive clay slate, a narrow strip of granite, and then the rock in question. Unfortunately the black powder was not preserved. It is not the least remarkable circumstance attending this curiosity, that had the saw passed the sixteenth part of an inch on one side, it would have injured the letters, or on the other they would not have appeared. No fissure or fracture was to be seen in the block.

Various conjectures have been made as to the characters; one gentleman insists that they are Hebrew, and stand for "Jehovah;" another says that they are the Roman "in" and correspond to "Jesus of Nazareth."— Both these persons of course believe that they have at some ancient period of time been put there by the hand of man; but by whom, or how they could afterwards have become buried in the solid rock, especially as it is primitive, they cannot explain. Others, among which number I confess myself, believe it to be a lusus naturae —all agree that it is a great curiosity, and well deserving examination.

I am yours, respectfully,

P. A. BROWNE.

From the Inquirer.

The following are letters from respectable gentlemen! at Norristown, in relation to the block of marble esteemed such a curiosity, and now in the possession of Peter A. Browne, Esq. of this city.

NORRISTOWN, March 25th, 1830.

I do hereby certify that I was present at Savage's Marble Saw Mill in this town, in the month of November last, immediately after a block of marble was brought there from Henderson's quarry, in Upper Merion township, Montgomery county, Pa.

The block contained about 30 cubic feet; the slab taken off by the saw, and now in possession of P. A. Browne, Esq. was about three feet wide and about six feet long: in the body of the marble exposed by the cutting, was an indentation about one and a half inches long, and about five-eighths of an inch wide, in which were the two raised letters "in." This indenture and these letters were examined by me within about an hour after the slab was sawed off', and when it was utterly impossible that any one who should have been so disposed, could have cut those letters; upon the corresponding slab there was no mark except that of the saw; in the indentation was a brownish black powder. The surface of the marble in the indentation, and that of the letters, appeared then, as they do now, to be vitrified or semi-chrystalized, and had not the slightest appearance of having been artificially done after the sawing of the block.

BENJAMIN BARTHOLOMEW.

NORRISTOWN, March 26th, 1830.

Dear Sir—In answer to your note, inquiring what t know relative to the slab cut from the block of marble brought from Henderson's quarry, and exhibiting an indentation and characters, I can say that I examined particularly the slab at the marble saw mill in the evening of the day upon which it was sawed, and then remarked the indentation and characters bearing exactly the appearance they now bear. I am positively certain in my own mind that no deception or art has been practised; but that, except the sawing, it remains in the same state in which it was taken from the quarry, which is primitive marble.

Very respectfully, your ob't serv't,

JOSEPH THOMAS.

CURIOSITY.

A solid block of white marble, of thirty cubic feet, was lately taken out of Henderson’s quarry, at the depth of seventy feet, four or five miles from Norristown, on the western side of the river Schuylkill. It was sent to Norristown, to be cut by the saw into slabs. One of these slabs presents to the eye a remarkable curiosity: On one of its sides are two characters, somewhat resembling the English word in, regularly cut into the marble. This singular appearance must either have been a freak of nature, or the work of man executed ages ago, and the marble must have been growing over it ever since; for it was found by the sawyer in the very interior of the block. The curious slab is now in possession of Col. Peter A. Browne, of this city, who will, we are sure, take pleasure in showing it to any gentleman who may be inquisitive on geological subjects.

Penn. Inquirer.

To the Editor of the Pennsylvania Inquirer. Sir—Observing that you have noticed, in your paper of Thursday last, the curious marble slab which I have in my possession, I will furnish you with some further particulars in relation to it. The block was taken out of Henderson's quarry, Upper Merion township, Montgomery county, Pennsylvania, between 60 and 70 feet below the surface of the earth; it measured upwards of SO cubic feet; it was purchased by Mr. Alexander Ramsey of Norristown, to whose liberality I am indebted for the slab, and was by him sent to Mr. Savage's marble saw mill to be cut. A slab two inches in thickness was taken off and displayed to view, nearly in the centre, an indentation 1J inch long by 5-8ths of an inch wide, handsomely arched above and rectangular below. In this cavity was a black powder, which being removed, TWO CHARACTERS were observed—These are raised, and are at equal distances from the top, bottom and sides of the indentation from each other. That the letters have not been put there since the block was cut, is proved by several gentlemen of Norristown of the highest respectability, who saw it soon after the sawing; and moreover, it is apparent to any person accustomed to examine mineral substances, that no tool whatever has been used; the surface of the indentation, as well as that of the letters, has a vitrified or semi-chrystallized appearance. Mr. Strickland and Mr. Peale, both of whom hate examined the slab carefully with a magnifying glass, agree with me in this particular. The marble belongs to the primitive limestone formation, which in this district is the last of the primitive scries, commencing at Philadelphia, and pursuing the following order: gneiss, mica-slate, hornblende, talcose slate, primitive clay slate, a narrow strip of granite, and then the rock in question. Unfortunately the black powder was not preserved. It is not the least remarkable circumstance attending this curiosity, that had the saw passed the sixteenth part of an inch on one side, it would have injured the letters, or on the other they would not have appeared. No fissure or fracture was to be seen in the block.

Various conjectures have been made as to the characters; one gentleman insists that they are Hebrew, and stand for "Jehovah;" another says that they are the Roman "in" and correspond to "Jesus of Nazareth."— Both these persons of course believe that they have at some ancient period of time been put there by the hand of man; but by whom, or how they could afterwards have become buried in the solid rock, especially as it is primitive, they cannot explain. Others, among which number I confess myself, believe it to be a lusus naturae —all agree that it is a great curiosity, and well deserving examination.

I am yours, respectfully,

P. A. BROWNE.

From the Inquirer.

The following are letters from respectable gentlemen! at Norristown, in relation to the block of marble esteemed such a curiosity, and now in the possession of Peter A. Browne, Esq. of this city.

NORRISTOWN, March 25th, 1830.

I do hereby certify that I was present at Savage's Marble Saw Mill in this town, in the month of November last, immediately after a block of marble was brought there from Henderson's quarry, in Upper Merion township, Montgomery county, Pa.

The block contained about 30 cubic feet; the slab taken off by the saw, and now in possession of P. A. Browne, Esq. was about three feet wide and about six feet long: in the body of the marble exposed by the cutting, was an indentation about one and a half inches long, and about five-eighths of an inch wide, in which were the two raised letters "in." This indenture and these letters were examined by me within about an hour after the slab was sawed off', and when it was utterly impossible that any one who should have been so disposed, could have cut those letters; upon the corresponding slab there was no mark except that of the saw; in the indentation was a brownish black powder. The surface of the marble in the indentation, and that of the letters, appeared then, as they do now, to be vitrified or semi-chrystalized, and had not the slightest appearance of having been artificially done after the sawing of the block.

BENJAMIN BARTHOLOMEW.

NORRISTOWN, March 26th, 1830.

Dear Sir—In answer to your note, inquiring what t know relative to the slab cut from the block of marble brought from Henderson's quarry, and exhibiting an indentation and characters, I can say that I examined particularly the slab at the marble saw mill in the evening of the day upon which it was sawed, and then remarked the indentation and characters bearing exactly the appearance they now bear. I am positively certain in my own mind that no deception or art has been practised; but that, except the sawing, it remains in the same state in which it was taken from the quarry, which is primitive marble.

Very respectfully, your ob't serv't,

JOSEPH THOMAS.

The Columbia Star and Christian Index (May 29, 1830)

INEXPLICABLE AND CURIOUS.

The marble slab from which the above figure was taken, is now in the possession of Peter A. Browne, Esq. of this city, and may be seen at his office in the Arcade. It was discovered in the following manner. A block of marble of the primitive limestone formation, measuring about 32 cubic feet, was recently cut from Henderson's quarry, Upper Merion township, Pa. 60 or 70 feet below the surface of the earth. This entire mass was purchased by Mr. Alexander Ramsey, of Norristown, and by him sent to the marble sawmill of Mr. Savage to be cut into suitable slabs. The section which contains the figure now before us is about two inches thick. The figure itself is an indentation of the form here represented, one inch and a quarter in length, and five eighths of an inch in breadth— and as will be seen, is handsomely arched above and rectangular below. It displayed itself to the workmen engaged in sawing the block of marble, near the centre of the surface through which the saw had passed, having the small cavity where the impression is, filled with black dust. Had the saw passed but the sixteenth of an inch out of the direction which it assumed, the whole impression would have been destroyed or else left invisible. That the characters were not made by any person after the marble was sawed, is proved by the testimony of highly respectable persons at Norristown. The same is proved by the vitrified, and semi-chrystallized appearance of the indentation. The most skilful mineralogists who have inspected it, agree that the figure could not have been made by recent art. This is a concise account of the facts attending the discovery.

The following are some of the conjectures which have been expressed respecting this singular impression, now brought out from the very centre of the marble rock, to be read and examined by the curious.

"These characters are considered by some persons to be a "yood" and a "hay," the first two Hebrew letters of the sacred name JEHOVAH: which name is formed by "yood hay" and "way hay."

"Others read them "heth" and "vauf," which stand for "Kaset" and "Vaemmet," "Piety and Truth," which among the ancient Jews was called the SEAL of the DEITY."

The Rev. Mr. Schrceder of New York inclines to the first opinion, but he thinks also that they may be numerical symbols, and would be "8000."

A writer who signed Werner, thinks that they are the fossil remains of some unknown animal.

Dr. Mitchell of New York believes it a natural crystallization and the form accidental.

In our view, it seems difficult to imagine that the characters here represented were formed by any other means than the art of man. The shadings of the marble, we are aware, exhibit a great variety of figures and outlines which a fertile imagination may construe into a thousand phantastic and visionary pictures. To such inherent colorings in the very texture of the primitive marble, the characters before us bear no sort of resemblance. To our apprehension there is no propriety in saying that it is a "lusus naturae," a mere freak of nature—since such things are ordinarily nothing more than spontaneous resemblances of natural, and not of artificial objects. Had the marble been imbedded with any of the secondary formations—there might have been room for conjecture as to its antediluvian origin—but being of the primitive order, which is generally considered as old as the earth itself —all imagination is confounded as to its possible origin. The science of geology is yet imperfect, though in the present day in rapid progression. To attempt therefore the construction of theories upon the insulated facts exhibited in earthy and mineral substances, would be as unphilosophical, as dangerous. We may, however, remark that the truth of Scripture both for its physical and moral bearing, receives accessions of light and confirmation, from all the discoveries of real science.

INEXPLICABLE AND CURIOUS.

The marble slab from which the above figure was taken, is now in the possession of Peter A. Browne, Esq. of this city, and may be seen at his office in the Arcade. It was discovered in the following manner. A block of marble of the primitive limestone formation, measuring about 32 cubic feet, was recently cut from Henderson's quarry, Upper Merion township, Pa. 60 or 70 feet below the surface of the earth. This entire mass was purchased by Mr. Alexander Ramsey, of Norristown, and by him sent to the marble sawmill of Mr. Savage to be cut into suitable slabs. The section which contains the figure now before us is about two inches thick. The figure itself is an indentation of the form here represented, one inch and a quarter in length, and five eighths of an inch in breadth— and as will be seen, is handsomely arched above and rectangular below. It displayed itself to the workmen engaged in sawing the block of marble, near the centre of the surface through which the saw had passed, having the small cavity where the impression is, filled with black dust. Had the saw passed but the sixteenth of an inch out of the direction which it assumed, the whole impression would have been destroyed or else left invisible. That the characters were not made by any person after the marble was sawed, is proved by the testimony of highly respectable persons at Norristown. The same is proved by the vitrified, and semi-chrystallized appearance of the indentation. The most skilful mineralogists who have inspected it, agree that the figure could not have been made by recent art. This is a concise account of the facts attending the discovery.

The following are some of the conjectures which have been expressed respecting this singular impression, now brought out from the very centre of the marble rock, to be read and examined by the curious.

"These characters are considered by some persons to be a "yood" and a "hay," the first two Hebrew letters of the sacred name JEHOVAH: which name is formed by "yood hay" and "way hay."

"Others read them "heth" and "vauf," which stand for "Kaset" and "Vaemmet," "Piety and Truth," which among the ancient Jews was called the SEAL of the DEITY."

The Rev. Mr. Schrceder of New York inclines to the first opinion, but he thinks also that they may be numerical symbols, and would be "8000."

A writer who signed Werner, thinks that they are the fossil remains of some unknown animal.

Dr. Mitchell of New York believes it a natural crystallization and the form accidental.

In our view, it seems difficult to imagine that the characters here represented were formed by any other means than the art of man. The shadings of the marble, we are aware, exhibit a great variety of figures and outlines which a fertile imagination may construe into a thousand phantastic and visionary pictures. To such inherent colorings in the very texture of the primitive marble, the characters before us bear no sort of resemblance. To our apprehension there is no propriety in saying that it is a "lusus naturae," a mere freak of nature—since such things are ordinarily nothing more than spontaneous resemblances of natural, and not of artificial objects. Had the marble been imbedded with any of the secondary formations—there might have been room for conjecture as to its antediluvian origin—but being of the primitive order, which is generally considered as old as the earth itself —all imagination is confounded as to its possible origin. The science of geology is yet imperfect, though in the present day in rapid progression. To attempt therefore the construction of theories upon the insulated facts exhibited in earthy and mineral substances, would be as unphilosophical, as dangerous. We may, however, remark that the truth of Scripture both for its physical and moral bearing, receives accessions of light and confirmation, from all the discoveries of real science.

American Journal of Science, vol. 19, no. 2 (January 1831)

10. Singular impression in marble.

TO PROF. B. SILUMAN.

Dear Sir—About twelve miles N. W. of this city, is a marble quarry owned by Mr. Henderson. It belongs to the primitive lime formation, and in this district forms the last of that series. The order in which the rocks repose are, commencing at Philadelphia, as follows; gneiss, mica slate, hornblende, talcose slate, primitive clay slate, a very narrow strip of eurite, and then the primitive lime rock, to which this belongs. The quarry has been worked for many years, in some places to the depths of sixty, seventy, and eighty feet. In the month of November last, a block of marble measuring upwards of thirty cubic feet, was taken out from the depth of between sixty and seventy feet, and sent to Mr. Savage's marble saw mill in Norristown to be cut into slabs. One was taken off about three feet wide and about six feet long, and in the body of the marble, exposed by the cutting, was immediately discovered an indentation, about one and a half inches long and about five eights of an inch wide, in which were the two raised characters. Fortunately, several of the most respectable gentlemen residing in Norristown were called upon to witness this remarkable phenomenon, without whose testimony it might have been difficult, if not impossible, to have satisfied the public, that an imposition had not been practised by cutting the indentation and carving the letters after the slab was cut off.

I send you a cast of the impressions by the bearer of this letter. I am Sir very sincerely, your obt. servt. J. B. BROWNE.

Philadelphia, April 1, 1830.

10. Singular impression in marble.

TO PROF. B. SILUMAN.

Dear Sir—About twelve miles N. W. of this city, is a marble quarry owned by Mr. Henderson. It belongs to the primitive lime formation, and in this district forms the last of that series. The order in which the rocks repose are, commencing at Philadelphia, as follows; gneiss, mica slate, hornblende, talcose slate, primitive clay slate, a very narrow strip of eurite, and then the primitive lime rock, to which this belongs. The quarry has been worked for many years, in some places to the depths of sixty, seventy, and eighty feet. In the month of November last, a block of marble measuring upwards of thirty cubic feet, was taken out from the depth of between sixty and seventy feet, and sent to Mr. Savage's marble saw mill in Norristown to be cut into slabs. One was taken off about three feet wide and about six feet long, and in the body of the marble, exposed by the cutting, was immediately discovered an indentation, about one and a half inches long and about five eights of an inch wide, in which were the two raised characters. Fortunately, several of the most respectable gentlemen residing in Norristown were called upon to witness this remarkable phenomenon, without whose testimony it might have been difficult, if not impossible, to have satisfied the public, that an imposition had not been practised by cutting the indentation and carving the letters after the slab was cut off.

I send you a cast of the impressions by the bearer of this letter. I am Sir very sincerely, your obt. servt. J. B. BROWNE.

Philadelphia, April 1, 1830.

A Greek Tomb in Uruguay

Nouvelles annales des voyages (vol. 1 for 1832)

Discovery of a Greek Tomb.

Abundant evidence leaves no doubt that the New World had been visited by the ancients centuries before Columbus. Without mentioning the temples of Mexico, which were built on the same plan as that of Delphi, here is a new proof of this assertion:

“In the village of Dolores, two leagues from Montevideo, a farmer discovered a tombstone with unknown characters. Under this stone, he found a brick vault containing two antique swords, a helmet and a shield quite damaged by rust, and an earthen amphora of great dimension. All this debris was sent to the scholar Father Martines, who managed to read the words in Greek characters on the stone: ‘Viou tou Filipp …… Alexand …… to … macdeo …… basi … epi tes execou …… k …… tri …… oly …… en to … top …… Ptolem ……,’ which is to say, in completing the words, ‘Alexander, the son of Philip, was king of Macedonia, during the 63rd Olympiad, to this place Ptolemy…,’ and the rest is missing.

“On the swords’ (sic) handle is engraved a portrait that appears to be that of Alexander, and on the helmet we see a carving representing Achilles dragging Hector’s corpse around the walls of Troy. Must we conclude from this discovery that a contemporary of Aristotle had set foot in Brazil? Is it likely that Ptolemy, the well-known head of the fleet of Alexander, driven by a storm, through what the ancients called the Great Sea, was thrown on the coasts of Brazil, and there marked his passage by this monument, making for a very curious case for archaeologists?” (Universal Gazette of Bogota.)

Translated by Jason Colavito.

Discovery of a Greek Tomb.

Abundant evidence leaves no doubt that the New World had been visited by the ancients centuries before Columbus. Without mentioning the temples of Mexico, which were built on the same plan as that of Delphi, here is a new proof of this assertion:

“In the village of Dolores, two leagues from Montevideo, a farmer discovered a tombstone with unknown characters. Under this stone, he found a brick vault containing two antique swords, a helmet and a shield quite damaged by rust, and an earthen amphora of great dimension. All this debris was sent to the scholar Father Martines, who managed to read the words in Greek characters on the stone: ‘Viou tou Filipp …… Alexand …… to … macdeo …… basi … epi tes execou …… k …… tri …… oly …… en to … top …… Ptolem ……,’ which is to say, in completing the words, ‘Alexander, the son of Philip, was king of Macedonia, during the 63rd Olympiad, to this place Ptolemy…,’ and the rest is missing.

“On the swords’ (sic) handle is engraved a portrait that appears to be that of Alexander, and on the helmet we see a carving representing Achilles dragging Hector’s corpse around the walls of Troy. Must we conclude from this discovery that a contemporary of Aristotle had set foot in Brazil? Is it likely that Ptolemy, the well-known head of the fleet of Alexander, driven by a storm, through what the ancients called the Great Sea, was thrown on the coasts of Brazil, and there marked his passage by this monument, making for a very curious case for archaeologists?” (Universal Gazette of Bogota.)

Translated by Jason Colavito.

A Gold Thread in Carboniferous Stone

London Times (June 22, 1844)

A few days ago, as some workmen were employed in quarrying a rock close to the Tweed about a quarter of a mile below Rutherford-mill, a gold thread was discovered embedded in the stone at a depth of eight feet

A few days ago, as some workmen were employed in quarrying a rock close to the Tweed about a quarter of a mile below Rutherford-mill, a gold thread was discovered embedded in the stone at a depth of eight feet

A Nail found Embedded in Prehistoric Sandstone

Report of the Fourteenth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, 1844 (1845)

Queries and Statements concerning a Nail found imbedded in a Block of Sandstone obtained from Kingoodie (Mylnfield) Quarry, North Britain. Communicated by Sir DAVID BREWSTER.

This communication, drawn up by Mr. Buist, consisted of a series of queries, with the answers that had been returned by different persons connected with the quarry, the inquiry being set on foot by persons present on the discovery of the nail or immediately afterwards. The following is the substance of the investigation.

1. The circumstance of the discovery of the nail in the block of stone.

The stone in Kingoodie quarry consists of alternate layers of hard stone and a soft clayey substance called “till;” the courses of stone varying from six inches to upwards of six feet in thickness. The particular block in which the nail was found, was nine inches thick, and in proceeding to clear the rough block for dressing, the point of the nail was found projecting about half an inch (quite eaten with rust) into the “till,” the rest of the nail laying along the surface of the stone to within an inch of the head, which went right down into the body of the stone. The nail was not discovered while the stone remained in the quarry, but when the rough block (measuring two feet in length, one in breadth, and nine inches in thickness) was being cleared of the superficial “till.” There is no evidence beyond the condition of the stone to prove what part of the quarry this block may have come from.

2. The condition of the quarry from which the block of stone was obtained.

The quarry itself (called the east quarry) has only been worked for about twenty years, but an adjoining one (the west quarry) has been formerly very much worked, and has given employment at one time to as many as 500 men. Very large blocks of atone have at intervals been obtained from both. It is observed that the rough block in which the nail was found must have been turned over and handled at least four or five times in its journey to Inchyra, at which place it was put before masons for working, and where the nail was discovered.

Queries and Statements concerning a Nail found imbedded in a Block of Sandstone obtained from Kingoodie (Mylnfield) Quarry, North Britain. Communicated by Sir DAVID BREWSTER.

This communication, drawn up by Mr. Buist, consisted of a series of queries, with the answers that had been returned by different persons connected with the quarry, the inquiry being set on foot by persons present on the discovery of the nail or immediately afterwards. The following is the substance of the investigation.

1. The circumstance of the discovery of the nail in the block of stone.

The stone in Kingoodie quarry consists of alternate layers of hard stone and a soft clayey substance called “till;” the courses of stone varying from six inches to upwards of six feet in thickness. The particular block in which the nail was found, was nine inches thick, and in proceeding to clear the rough block for dressing, the point of the nail was found projecting about half an inch (quite eaten with rust) into the “till,” the rest of the nail laying along the surface of the stone to within an inch of the head, which went right down into the body of the stone. The nail was not discovered while the stone remained in the quarry, but when the rough block (measuring two feet in length, one in breadth, and nine inches in thickness) was being cleared of the superficial “till.” There is no evidence beyond the condition of the stone to prove what part of the quarry this block may have come from.

2. The condition of the quarry from which the block of stone was obtained.

The quarry itself (called the east quarry) has only been worked for about twenty years, but an adjoining one (the west quarry) has been formerly very much worked, and has given employment at one time to as many as 500 men. Very large blocks of atone have at intervals been obtained from both. It is observed that the rough block in which the nail was found must have been turned over and handled at least four or five times in its journey to Inchyra, at which place it was put before masons for working, and where the nail was discovered.

A Mysterious Pot in Ancient Rock

Scientific American, vol. 7 (July 5, 1852)

A few days ago a powerful blast was made in the rock at Meeting House Hill in Dorchester, a few rods south of Rev. Mr. Hall's meeting house. The blast threw out an immense mass of rock, some of the pieces weighing several tons and scattered small fragments in all directions. Among them was picked up a metallic vessel in two parts rent asunder by the explosion. On putting the two parts together it formed a bell shaped vessel, 4½ inches high, 6½ inches at the base 2½ inches at the top, and about an eighth of an inch thickness. The body of this vessel resembles zinc in color or a composition metal, in which there is a considerable portion of silver. On the sides there are six figures of a flower or bouquet beautifully inlaid with pure silver, and around the lower part of the vessel a vine or wreath, inlaid also with silver. The chasing, carving, and inlaying are exquisitely done by the art of some cunning workman. This curious and unknown vessel was blown out of the solid pudding stone, fifteen feet below the surface. It is now in the possession of Mr John Kettell. Dr. J. V. C. Smith who has recently travelled in the east and examined hundreds of curious domestic utensils and has drawings of them, has never seen anything resembling this. He has taken a drawing and accurate dimensions of it to be submitted to the scientific community. There is no doubt but that this curiosity was blown out of the rock, as above stated; but will Professor Agassiz or some other scientific man please to tell us how it came there? The matter is worthy of investigation as there is no deception in the case.

[ The above is from the Boston Transcript and the wonder is to us, how the Transcript can suppose Prof. Agassiz qualified to tell how it got there any more than John Doyle, the blacksmith. This is not a question of zoology, botany, or geology, but one relating to an antique metal vessel perhaps made by Tubal Cain, the first inhabitant of Dorchester.

A few days ago a powerful blast was made in the rock at Meeting House Hill in Dorchester, a few rods south of Rev. Mr. Hall's meeting house. The blast threw out an immense mass of rock, some of the pieces weighing several tons and scattered small fragments in all directions. Among them was picked up a metallic vessel in two parts rent asunder by the explosion. On putting the two parts together it formed a bell shaped vessel, 4½ inches high, 6½ inches at the base 2½ inches at the top, and about an eighth of an inch thickness. The body of this vessel resembles zinc in color or a composition metal, in which there is a considerable portion of silver. On the sides there are six figures of a flower or bouquet beautifully inlaid with pure silver, and around the lower part of the vessel a vine or wreath, inlaid also with silver. The chasing, carving, and inlaying are exquisitely done by the art of some cunning workman. This curious and unknown vessel was blown out of the solid pudding stone, fifteen feet below the surface. It is now in the possession of Mr John Kettell. Dr. J. V. C. Smith who has recently travelled in the east and examined hundreds of curious domestic utensils and has drawings of them, has never seen anything resembling this. He has taken a drawing and accurate dimensions of it to be submitted to the scientific community. There is no doubt but that this curiosity was blown out of the rock, as above stated; but will Professor Agassiz or some other scientific man please to tell us how it came there? The matter is worthy of investigation as there is no deception in the case.

[ The above is from the Boston Transcript and the wonder is to us, how the Transcript can suppose Prof. Agassiz qualified to tell how it got there any more than John Doyle, the blacksmith. This is not a question of zoology, botany, or geology, but one relating to an antique metal vessel perhaps made by Tubal Cain, the first inhabitant of Dorchester.

A Sphere from the Tertiary Period

The Geologist 5 (April 1862)

M. Melleville, the Vice-President of the Société Academique of Laon, has published an account in the ‘Revue Archéologiquc’ of an object of human workmanship found in the lignites of that neighbourhood.

Starting on the basis that man was contemporaneous with the great carnivora and herbivora, and that objects of his workmanship are found with their bones, he goes on to make out that the beds containing them differ from the diluvium as much in the materials of which they are formed as in the fossils they contain, and that they are more ancient than it as they are everywhere covered by it. Those deposits belong to that geological age, which immediately preceded the present era; whilst it is admitted that the diluvium marks the commencement of the recent or historic period. The ultimate consequence he deduces from the published observations on this subject is, that there are two stone-ages—the first ante-historic, corresponding to the epoch of the formation of the lacustrine bed of the Somme, and characterized by large implements entirely of flints chipped but never ground; the other by far more finished and various products, indicating a more advanced art and established relations between the different tribes which at that period inhabited France. These premises he merely puts forward, reserving for a future occasion the discussion which alone can establish their correctness. What he desires to do now is to show that the field of discovery as to the antiquity of the human race is at least open, and that this question, already so wide from the little we as yet know, seems likely to be spread still wider by such discoveries as that of which he gives the details.

An object “incontestably fashioned by the hand of man” has been found at a depth of 75 metres from the soil, in a perfectly virgin bed of the lignites or “cendres noires” at Laon, the geological age of which goes back, as is known, to the earliest times of the Paris basin deposit*. Not but that objects of modern production have been found in these very beds, and he cites particularly a flint “hache,” which was found fourteen years since at 25 feet under ground, in the middle even of the lignites quarried near the village of Lille, canton of Fère, department of Aisne. But these facts, besides being so rare, are capable, in general, of being explained by accidental causes of entombment, the lignites of the Laonuois and of the Soissonois lying ordinarily at the surface or only being covered by foreign deposits of no great thickness. This is not the case with the ash-bed of Montaigu, near Laon, whence the object in question comes. “The exceptional conditions of the bedding where it was found is precisely that which gives to this discovery a special interest, and perhaps a considerable value; and it is thus necessary to give here a slightly detailed description, and to make known the method of quarrying.”

“The lignites worked for agricultural purposes near the village of Montaigu, four leagues north-east of Laon, occupy the foot of a Tertiary hill, constituted at its base of clays, amongst which these lignites are intercalated; in the middle, of thick masses of sand, enclosing some beds of shells; and at the summit by newer clays superposed on thick beds of hard rock—the Calcaire qrossier of geologists, which form the crown of the hill. The ‘ ash-bed’ is quarried by means of subterranean galleries, which extend in different directions under the hill—the principal one being driven into the centre of it for a considerable distance, its extremity not being less than GOO metres from the point where it opens on the valley. This bed is about 2 30 metres thick, and is covered by another bed of marly and sandy clay, full of fossil shells peculiar to that age--Cyreua cuneijormis, Ostrca bellovacina, etc., and which serves for the roof or ceiling of the quarry. This roof is sustained by means of wooden shores placed under and across as the gallery extends; the head only of the gallery being left free for the work of extraction. The ‘ash-bed,’ attacked at the foot, falls down into the space called the ‘chamber,’ detaching itself cleanly from the roof alluded to; and then the ‘ashes’ are put into small waggons running on an iron tramway. These ‘waggons’ in their turn are pushed by men out of the quarry, and the 1 ash’ is discharged and made into a heap for burning before being sold for agriculture. In the month of August last year (1861) the workmen employed at the end of the principal gallery, in throwing down a block of ‘ashes,’ observed with surprise an object detach itself and roll to some distance. Struck with this incident, such as had never before happened to them, they hastened to search for it, and found a ball of moderate dimensions. But their astonishment was increased when on examining it they thought they recognized it as the work of man’s hand. They looked then to see exactly what place in strata it had occupied, and they are able to state that it did not come from the interior of the ‘ash,’ but that it was imbedded at its point of contact with the roof of the quarry, where it had left its impression indented. Better judging than many other workmen who daily make similar discoveries without informing any one of them, these of Montaigu at once carried the object found to Dr. Lejeune, the proprietor of the ‘ash’ quarry, whose house was close by. It could not have fallen into better hands. At the first glance M. Lejeune saw that the ball was really of human workmanship, and he in his turn hastened to inform me of the circumstances of the discovery, no similar occurrence to which, as I have paid, has happened within the memory of the workmen. However, long before this discovery, the workmen of the quarry had told me they had many times found pieces of wood changed into stone (the wood which is found in the lignites is nearly always, as we know, transformed into silex) bearing the marks of human work. I regret greatly now not having asked to see these, but I did not hitherto believe in the possibility of such a fact.

“I ought to add that no suspicion of deception can be entertained. The workmen who found the ball had never heard of M. Boucher de Perthes and his discoveries, nor of the high questions of archaeology to which the presence of worked-flints deep in the earth have given rise. The ball of the ‘ash-bed’ of Montaigu carries also upon itself the mark of its own antiquity. It is easy to assure ourselves, on examining it with attention, that if it be permissible still to doubt whether its embedment dates back to the time when the bed was formed in which it was enclosed, it cannot be denied that its burial is ancient, and goes back to a period greatly remote from our own. The diameter of the ball is 6 centimetres, and it weighs 310 grammes, or about 10 ounces. It is of white chalk, and in this respect is distinguished from the stone-shot made use of for the artillery of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. These are constantly of sandstone or other hard and heavy rock. I have never seen one in chalk. Its form is imperfectly spherical, and its fracture unequal; it seems to have been fashioned with an instrument more blunt than cutting, from which one would suppose that the maker had only coarse and ineffectual tools. Three great splinters with sharp angles, announce also that it had remained during the working attached to the block of stone out of which it was made, and that it had been separated only after it was finished, by a blow, to which this kind of fracture is due.

“The workmen declare, as I have said, that the ball before falling to the ground was placed between the ‘ash-bed’ and the shell-bed which covered it. Its examination confirms in every way this assertion. It is really penetrated over four-fifths of its height by a black bituminous colour, that merges towards the top into a yellow circle, and which is evidently due to the contact of the lignite in which it had been for so long a time plunged. The upper part, which was in contact with the shell-bed, on the contrary has preserved its natural colour—the dull white of the chalk.