Les Évangiles sans Dieu

1886

translated by Jason Colavito

2016

|

NOTE |

The claim that Mary Magdalene and Jesus married and had children is often associated with the 1980s bestseller The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, but the claim had appeared a century earlier in a book published in France in 1886 under the name Louis Martin called Les Évangiles sans Dieu (“The Gospels without God”), also published in his 1887 book Essai sur la vie de Jésus. The real Louis Martin, a Freemason, wrote the Holy Bloodline conspiracy book, but an anti-Masonic conspiracy theorist by the name of Léon Aubry used the same name in writing anti-Masonic and anti-Semitic conspiracy theories. The former sued the latter, making him the first Holy Bloodline author involved in a lawsuit over his books when the real Martin sued the fake one for stealing his identity.

This page presents the relevant excerpt from the chapter called “Love and Removal” in The Gospels without God in which Martin describes the birth of the son of Mary Magdalene and Jesus Christ, based only on a name, as well as supplementary materials on the reception and impact of the volume in France in the late 1800s. Special thanks to David Bradbury, who provided me with the French text of the chapter from The Gospels without God. |

THE GOSPELS WITHOUT GOD

Love and Removal

|

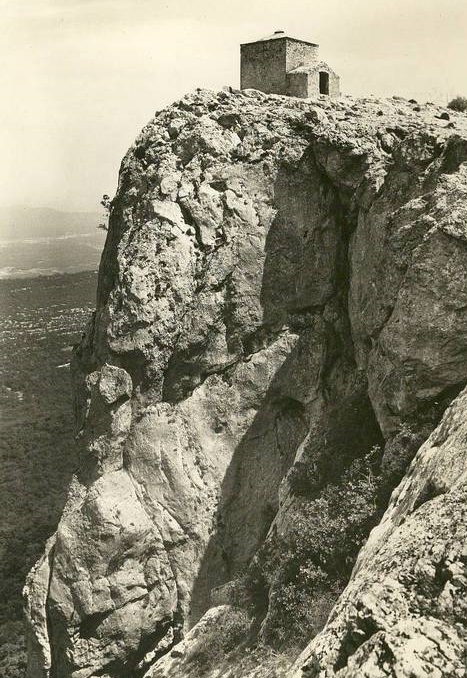

At Saint-Pilon, with his face turned towards the sea, the traveler need only take a few steps to meet a hidden course among all these projecting rocks that are piled at his feet, a narrow opening into which a man’s body can quickly disappear; it is, in its current state, the entrance to a wide and extraordinarily deep underground passage that opens immediately underfoot. We descend there using a strongly knotted rope ladder; then at this depth we fall into another, and we follow the meanders that intersect to infinity, and if we do lose our way we end up going from abyss to abyss until we break through out of the cave that opens full wide before the forest.

Local traditions, which always have their basis in some probability, say that the Angels every day removed the Magdalene and deposited her on top of this rock. She then, by this mysterious method, enjoyed this wonderful view, which is a delight; having at her feet to one side the dark forest, extending away like a huge green carpet; all around, the scorching nature of the perfumed breath of the distant country, and facing the blue sea and clear sky. Then, when she had imbibed deeply of life, she returned to fall into contemplation of Him who was the life of her heart and always alive for her, and she held the cold remains in her hands, pressing them to the burning lips of the woman. |

*

* *

* *

Love is so made that once illuminated, it never goes out. Its flame passes from the torch of marriage to the most peaceful glow of the domestic hearth without ceasing to shine in all its brilliance. Once close to the heart of man, the heart of the woman continues to beat in the unity of two hearts: first burning with the husband, then warming with the son; serving as a bridge between these two beings who are joined within it. By consequence, the result is always a happy one because she is always loving, always loved and whether wife or mother she is always sovereign. This second kingdom soon came to divert Mary Magdalene from the dark drama she had hitherto seen play out constantly beneath her eyes. The moment, for her, had come to bring His fruit into the world.

*

* *

* *

Of that event there remains nary a trace, almost nothing, nothing but a name. But this name, wonderfully intentional, coupled with that of the lover of Christ, suffices to dispel all darkness that has accumulated as a thick curtain between these lives and our legitimate curiosity. It is the name of this selfsame child.

Choosing a name for the first fruit of their love is the first challenge for mothers in the delightful time following a birth. How does one name this frail life, which the whole life of two people, the treasure that alone is worth all the wealth of the earth, this joy that intoxicates them, and this pride that gratifies them so much?

Each detaches from the sky a star, the brightest, to adorn the forehead of the newborn; others in the light of day find some marvel they compare him to, or they delight in a spring flower that his parents place on his crib as a graceful emblem, one that has the most crimson, great freshness, and that stands valiantly on its stem, unrivaled because he has a name that is unrivaled, completely unique!

So certainly thought Mary Magdalene, contemplating the beloved hanging from her breast, who was babbling before he could speak, and so adorably demanding in return that she love him as much as she had loved his father. Like all who are similarly happy, she was worried about the loving name of this son, but like those who previously cried but henceforth will smile, she found herself comforted by a dazzling new vision. She saw the one she loved transfigured into the one she was now to love; the greatness of the soul of her “Lord” now living took the place of the memory of His wounds; the blood, the torture, and his death—this bleak vision vanished before the dazzling beauty and grandeur, the manliness of his proud existence; and in an outburst of maternal satisfaction, she wrapped her son in the glorious halo of his father with one of the only Latin words of which she knew the meaning, naming him “Maximin.”

Maximin, from “Maximinus,” means: “descended from that which is the greatest in the world;” it means the son of a man great beyond all expression; in a word, the little one of the great one.

The last and precious token of the love of the Magdalene for Christ has become for us a provident one and, certainly, the most unexpected of testimony. A name, from a less intimate relationship, would have been nothing.

Choosing a name for the first fruit of their love is the first challenge for mothers in the delightful time following a birth. How does one name this frail life, which the whole life of two people, the treasure that alone is worth all the wealth of the earth, this joy that intoxicates them, and this pride that gratifies them so much?

Each detaches from the sky a star, the brightest, to adorn the forehead of the newborn; others in the light of day find some marvel they compare him to, or they delight in a spring flower that his parents place on his crib as a graceful emblem, one that has the most crimson, great freshness, and that stands valiantly on its stem, unrivaled because he has a name that is unrivaled, completely unique!

So certainly thought Mary Magdalene, contemplating the beloved hanging from her breast, who was babbling before he could speak, and so adorably demanding in return that she love him as much as she had loved his father. Like all who are similarly happy, she was worried about the loving name of this son, but like those who previously cried but henceforth will smile, she found herself comforted by a dazzling new vision. She saw the one she loved transfigured into the one she was now to love; the greatness of the soul of her “Lord” now living took the place of the memory of His wounds; the blood, the torture, and his death—this bleak vision vanished before the dazzling beauty and grandeur, the manliness of his proud existence; and in an outburst of maternal satisfaction, she wrapped her son in the glorious halo of his father with one of the only Latin words of which she knew the meaning, naming him “Maximin.”

Maximin, from “Maximinus,” means: “descended from that which is the greatest in the world;” it means the son of a man great beyond all expression; in a word, the little one of the great one.

The last and precious token of the love of the Magdalene for Christ has become for us a provident one and, certainly, the most unexpected of testimony. A name, from a less intimate relationship, would have been nothing.

*

* *

* *

After that, nothing is known, except that Mary Magdalene lived for another twenty-five years, and that her son, whom she had the satisfaction of seeing grow into a man, survived her for thirty years. After having deposited the body of his mother in an alabaster tomb, in commemoration of the memorable actions of his life, Maximin was in turn placed beside her in a marble tomb in the mausoleum which had been built by him and which bore his name.

According to this tradition, Mary Magdalene was dead at the time of the dispute at Antioch between Peter and Paul; and Maximin was dead at the time when St. Paul, having become free, founded the Church of Rome; both died before Christianity came out of its swaddling clothes.

Source: Louis Martin, Les Évangiles sans Dieu (Paris: Dentu & Cie,1887), 268-273.

According to this tradition, Mary Magdalene was dead at the time of the dispute at Antioch between Peter and Paul; and Maximin was dead at the time when St. Paul, having become free, founded the Church of Rome; both died before Christianity came out of its swaddling clothes.

Source: Louis Martin, Les Évangiles sans Dieu (Paris: Dentu & Cie,1887), 268-273.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

G. Meunier, Review of The Gospels without God

The Gospels without God. In regard to the title of this book, which is something of a paradox, the author has taken care to explain it from the very first pages of its very interesting philosophical preface: It is a work of atheism.

“Atheism is the only system that can lead man to freedom,” said Diderot; Martin develops this aphorism and concludes that, since disbelief in religion and understanding of science have actually begun to penetrate the minds of the masses, it would not be long until men attain freedom. Theism, he said in substance, remains on earth and seems to hold power because of certain residual habits and some hypocrisy that prevent admission of what everyone thinks quietly. Similarly, for believers, it is evident that God does not exist, and often those we take for such are not, but innovators who defer to the idea of a cosmic god and abandon the god of revelation, in a spirit of harmony or the pure reason of moral utility. — Seeing there, and rightly, that substitution of principles, this change in prejudice, Mr. Louis Martin began to wrest from the domain of thought all illusions, conceptions that are related to this always-pernicious belief in the same.

This task seems to him much easier because theocratic institutions have successively sunk into indifference or contempt. From these same metaphysical declines, soon and finally nothing will remain of what is called Providence, without which we can no longer determine the key attributes of the supreme intelligence, which the concept of a universal mind tried to clarify. On all of the sequentially accumulated ruins of religion Mr. Martin succeeds in building up by the principle of negation, thereby rebuilding a Gospel where Jesus, stripped of divinity which was decked in the fanaticism and superstition of ancient times, is made into a thinking human as an incarnation of a latent genius that produced through the ages a mysterious work of revolution, and therefore returns him to his rightful place as claimant and martyr. — Here, first of all, Mr. Martin may wish to allow us to make this remark, which is not as important as you might think: If God is to be placed at the door of this semi-religious monument which is called the Gospel, it loses nor gains in having a God or lacking one, since in any case, as Mr. Martin notes, its influence is negative because of the increasingly positive state today of the human mind: hence, by such rigor, one might conclude that the exegetical controversy is useless, completely useless.

The life of Jesus has already been well disputed; it was furiously dissected in the old days, his very existence is disputed, along with supporting documents and texts. Here precisely to resolve the debate, our author comes brandishing a new thesis sharpened well, thoroughly drenched in the pure sources of truth according to St. Matthew and St. Luke, who themselves are not in agreement as early on as establishing the genealogy of Christ. Fiction against fiction, I do not distinguish what need there may be to battle with the dead to destroy an enemy that we conclude does not exist, that is to say to remove a myth from a legend in order to purify that whose inspiration was a myth. But this assessment is very personal and is not, of course, relevant to a work, already weakened by the secondary role awarded to women, whose social perspective, aside from that, retains some philosophical and literary value; and is luxuriously edited.

Some chapters are very remarkable, yet not as scholarly as the poetic spirit and talent they reveal. Some pages are suffused with a warm lyricism that is nothing less than orthodox, and would have delightfully surprised Alemann, the father of the genre; and those related to Jesus’ love affair with Mary Magdalene would undoubtedly be envied by Anacreon of Theos if these two poets had not already been dead for a long time. For example, it could not be that Mr. Martin hoped for the praises of two thousand Catholic theologians, were his work to fall under their eyes, which cannot fail to happen. It is probable that, on the contrary, this exegesis, too modern for them, they cannot accept and that two centuries earlier it would have earned its author the honor of an apotheosis, and a beautiful auto-da-fe.

All the interpreters who serve the church, which is to say all of those who claim the power to interpret the Holy Scriptures, would comment in vain on the Gospels according to Mr. Martin in order to extract something sacred and mystical. But where their embarrassment fast grows to stupefaction occurs at the end of the volume, in the chapter concerning the removal of the body of the Crucified, in which they would learn that it was not abandoned in the tomb in Jerusalem but with the complicity of Mary Magdalene and some of his Disciples, it came to rest in the land of cicadas, of poets, and especially of hyperbole: in our own Provence! If this discovery is not refuted, it would shine a bright light on a few of the miracles attributed to Jesus during his lifetime, such as the wedding at Cana, the multiplication of bread, etc.; then the resurrection, too. There would be no place, then, for surprise that these facts have acquired a kind of posthumous and piquant splash, a very southern flavor that is religiously preserved and transmitted in all the texts, whose inadequacy Mr. Martin demonstrates with a rare talent.

Source: G. Meunier, “Revue des Livres,” La revue socialiste 6 (1887): 667-669.

“Atheism is the only system that can lead man to freedom,” said Diderot; Martin develops this aphorism and concludes that, since disbelief in religion and understanding of science have actually begun to penetrate the minds of the masses, it would not be long until men attain freedom. Theism, he said in substance, remains on earth and seems to hold power because of certain residual habits and some hypocrisy that prevent admission of what everyone thinks quietly. Similarly, for believers, it is evident that God does not exist, and often those we take for such are not, but innovators who defer to the idea of a cosmic god and abandon the god of revelation, in a spirit of harmony or the pure reason of moral utility. — Seeing there, and rightly, that substitution of principles, this change in prejudice, Mr. Louis Martin began to wrest from the domain of thought all illusions, conceptions that are related to this always-pernicious belief in the same.

This task seems to him much easier because theocratic institutions have successively sunk into indifference or contempt. From these same metaphysical declines, soon and finally nothing will remain of what is called Providence, without which we can no longer determine the key attributes of the supreme intelligence, which the concept of a universal mind tried to clarify. On all of the sequentially accumulated ruins of religion Mr. Martin succeeds in building up by the principle of negation, thereby rebuilding a Gospel where Jesus, stripped of divinity which was decked in the fanaticism and superstition of ancient times, is made into a thinking human as an incarnation of a latent genius that produced through the ages a mysterious work of revolution, and therefore returns him to his rightful place as claimant and martyr. — Here, first of all, Mr. Martin may wish to allow us to make this remark, which is not as important as you might think: If God is to be placed at the door of this semi-religious monument which is called the Gospel, it loses nor gains in having a God or lacking one, since in any case, as Mr. Martin notes, its influence is negative because of the increasingly positive state today of the human mind: hence, by such rigor, one might conclude that the exegetical controversy is useless, completely useless.

The life of Jesus has already been well disputed; it was furiously dissected in the old days, his very existence is disputed, along with supporting documents and texts. Here precisely to resolve the debate, our author comes brandishing a new thesis sharpened well, thoroughly drenched in the pure sources of truth according to St. Matthew and St. Luke, who themselves are not in agreement as early on as establishing the genealogy of Christ. Fiction against fiction, I do not distinguish what need there may be to battle with the dead to destroy an enemy that we conclude does not exist, that is to say to remove a myth from a legend in order to purify that whose inspiration was a myth. But this assessment is very personal and is not, of course, relevant to a work, already weakened by the secondary role awarded to women, whose social perspective, aside from that, retains some philosophical and literary value; and is luxuriously edited.

Some chapters are very remarkable, yet not as scholarly as the poetic spirit and talent they reveal. Some pages are suffused with a warm lyricism that is nothing less than orthodox, and would have delightfully surprised Alemann, the father of the genre; and those related to Jesus’ love affair with Mary Magdalene would undoubtedly be envied by Anacreon of Theos if these two poets had not already been dead for a long time. For example, it could not be that Mr. Martin hoped for the praises of two thousand Catholic theologians, were his work to fall under their eyes, which cannot fail to happen. It is probable that, on the contrary, this exegesis, too modern for them, they cannot accept and that two centuries earlier it would have earned its author the honor of an apotheosis, and a beautiful auto-da-fe.

All the interpreters who serve the church, which is to say all of those who claim the power to interpret the Holy Scriptures, would comment in vain on the Gospels according to Mr. Martin in order to extract something sacred and mystical. But where their embarrassment fast grows to stupefaction occurs at the end of the volume, in the chapter concerning the removal of the body of the Crucified, in which they would learn that it was not abandoned in the tomb in Jerusalem but with the complicity of Mary Magdalene and some of his Disciples, it came to rest in the land of cicadas, of poets, and especially of hyperbole: in our own Provence! If this discovery is not refuted, it would shine a bright light on a few of the miracles attributed to Jesus during his lifetime, such as the wedding at Cana, the multiplication of bread, etc.; then the resurrection, too. There would be no place, then, for surprise that these facts have acquired a kind of posthumous and piquant splash, a very southern flavor that is religiously preserved and transmitted in all the texts, whose inadequacy Mr. Martin demonstrates with a rare talent.

Source: G. Meunier, “Revue des Livres,” La revue socialiste 6 (1887): 667-669.

Maurice Vernes, Review of The Gospels without God

Louis Martin’s thesis is certainly strange. […] At the root of this pretentious and bombastic essay, there is no specific knowledge of the texts or questions related to the beginnings of Christianity. It reads, in fact, as an exegetical discussion of assertions such as the following: “It is known that God does not exist,” and there is detailed information on the relationship of Christ with Mary Magdalene.

Mr. Martin, who presents himself as a free thinker and a man of science and progress, cannot distinguish between facts acquired from history to a greater or lesser extent and legends drawn straight out of the air. Much of this volume is intended to establish that, through the efforts of Mary Magdalene, Jesus’ body was taken to Provence, Mary Magdalene and the family of Lazarus went to stay with these holy relics, and that the former gave birth to a son named Maximin, the fruit of her love for Christ.

Source: Maurice Vernes, “Histoire et Philosophie Religieuses,” Revue philosophique 25 (1888), 653.

Mr. Martin, who presents himself as a free thinker and a man of science and progress, cannot distinguish between facts acquired from history to a greater or lesser extent and legends drawn straight out of the air. Much of this volume is intended to establish that, through the efforts of Mary Magdalene, Jesus’ body was taken to Provence, Mary Magdalene and the family of Lazarus went to stay with these holy relics, and that the former gave birth to a son named Maximin, the fruit of her love for Christ.

Source: Maurice Vernes, “Histoire et Philosophie Religieuses,” Revue philosophique 25 (1888), 653.

Review of The Gospels without God

The Gospels without God, by Martin (Dentu): The title is quite banal, but the work is most certainly not, because what Mr. Martin has the ambition to prove is that Christ was an atheist; but to make even more piquant his demonstration, the author does not wish to seek his evidence and arguments anywhere else than in the Gospels. Let us add that Mr. Martin is absolutely sincere and acting in good faith, and that he often puts a real eloquence in the service of his strange assertions.

Source: La Nouvelle Revue 50 (1888), 937.

Source: La Nouvelle Revue 50 (1888), 937.

Hippolyte Barnout, The World without God

But that is not all; because, if by his family, especially his brothers, Jesus enters the human order, he returned there also by the offspring attributed to him, a certain Saint Maximin, the fruit of his love affair with the Magdalene, a version accepted by Lacordaire himself in his beautiful book on Mary Magdalene and recalled recently by Mr. Louis Martin in the Gospels without God, a rigorous historical study, based on real facts, that he just released.

Source: Hippolyte Barnout, Le monde sans dieu et le dernier mot de tout (Paris: C. Marpon et E. Flammarion, 1890), 389.

Source: Hippolyte Barnout, Le monde sans dieu et le dernier mot de tout (Paris: C. Marpon et E. Flammarion, 1890), 389.

CIVIL COURT OF THE SEINE

(First Chamber)

Mr. Poncet, Presiding.

Hearing of December 26, 1896.

Hearing of December 26, 1896.

Ownership right of an author to his patronym. — Theft by a third party — An almost criminal offense. — Joint and several liability of the author and publisher.

The author who appeared to have written books or newspaper articles under his surname has the right to object to a third published under the same name, books that could be attributed to him; he may receive compensation for the damage caused to him by this name theft, even unintentionally.

The Editor is responsible if he knew that. This responsibility is then shared between the Author and the Publisher, and, therefore, neither of them can act as collateral against the other.

The author who appeared to have written books or newspaper articles under his surname has the right to object to a third published under the same name, books that could be attributed to him; he may receive compensation for the damage caused to him by this name theft, even unintentionally.

The Editor is responsible if he knew that. This responsibility is then shared between the Author and the Publisher, and, therefore, neither of them can act as collateral against the other.

THE CASE OF LOUIS MARTIN AGAINST AUBRY AND SAVINE

The Court,

Regarding the complaint of Louis Martin against Aubry and Savine;

Whereas Léon Aubry wrote, and Savine published under the name of Louis Martin, a book entitled The Englishman Is Jewish? and another book entitled England and Freemasonry;

Whereas Louis Martin, author of a book and several pamphlets he did publish under his name, and items that were inserted under his signature, in various newspapers and magazines, unquestionably has the right to object to Léon Aubry usurping the name of Louis Martin, and publishing books under that name that could be attributed to him;

Whereas, on the other hand, he has the right under Articles 1382 and 1383 of the Civil Code, to demand compensation for the damage caused to him by this name theft, whether intentional or only as the result of a simple imprudence, which resulted in using a pseudonym without making sure it was not the name of another author;

Whereas Savine, publishing the aforementioned works under the name of Louis Martin when he knew that the author was called Léon Aubry, is guilty of the same tort, and incurs the same responsibilities; he vainly argues that his role was limited to copying and putting on sale the incriminating works; it is apparent from an examination of agreements concluded between Aubry and he that he edited the above books, the covers of which list: “Savine, publisher,” and that the contract by him allegedly refers only to five hundred unsold copies of a previous edition of England and Freemasonry, by a Mr. Grazillier;

Whereas, therefore, we advise, as will be made in the formal judgment on the termination of this proceeding, Louis Martin complains rightly;

Whereas, for the determination of damages, the Court must consider the fact that the theft committed has led to justifiable confusion between the real Louis Martin and the usurper of his name, and resulted in attributing to him the authorship of works designed in a totally different spirit than the works of which he is the author; the Court has the necessary elements to assess that damage to amount of five hundred francs; and that it is necessary to jointly condemn Savine and Aubry, the payment of that sum by reason of the indivisibility of the offense committed;

As for the warranty or guarantee brought by Savine against Aubry:

Whereas Savine having personally associated with the almost criminal acts of Aubry, is not entitled to act as collateral against him;

As for the action in warranty brought by Aubry against Savine:

Whereas this cannot be accepted, for the same reason; Aubry vainly alleges that it is the actions of Savine which have made it impossible to change his pseudonym on both incriminating books; but this does not prove that he regularly put Savine on notice to change his alias or stop the sale of the works in question; that the two letters of 6 and 15 March, 1896, and the proceedings which followed against Savine before the Commercial Court are unrelated to the current debates; that, moreover, if, in his letter of 6 March, of which it is only known that he spoke of the copies which he had produced, Savine’s press sent him all unsold copies, in total 15, he no longer asked that he make available 200 copies of The Englishman Is Jewish?

Whereas, finally, he has not exercised the option, by which Savine could strip his name, and insert, as requested by Louis Martin, corrective articles in newspapers;

In terms of Aubry’s claim, seeking that the Court reject the correspondence between Louis Martin and Aubry, and condemn Louis Martin to pay him 10,000 francs in damages for trying to introduce this correspondence into the proceedings;

Whereas these claims were abandoned at the hearing and are, moreover, unfounded;

For these reasons;

We prohibit Louis (sic) Aubry and Savine from editing and selling in the future, under the name of Louis Martin, the books entitled: England and Freemasonry and The Englishman Is Jewish?

We now award damages at a rate of 25 francs for each copy of the said works put up for sale under that name; and for compensation for the damage already caused, we award in total 500 francs of damages.

We declare Louis Martin ill-founded in the rest of his claims, which we dismiss.

We declare Aubry ill-founded in his claims against Louis Martin, which we dismiss.

We declare Léon Aubry and Savine respectively ill-founded in their claims and guarantees, etc.

“Jurisprudence de la Presse,” Le Bulletin de la Presse, January 25, 1897, 11-12.

Regarding the complaint of Louis Martin against Aubry and Savine;

Whereas Léon Aubry wrote, and Savine published under the name of Louis Martin, a book entitled The Englishman Is Jewish? and another book entitled England and Freemasonry;

Whereas Louis Martin, author of a book and several pamphlets he did publish under his name, and items that were inserted under his signature, in various newspapers and magazines, unquestionably has the right to object to Léon Aubry usurping the name of Louis Martin, and publishing books under that name that could be attributed to him;

Whereas, on the other hand, he has the right under Articles 1382 and 1383 of the Civil Code, to demand compensation for the damage caused to him by this name theft, whether intentional or only as the result of a simple imprudence, which resulted in using a pseudonym without making sure it was not the name of another author;

Whereas Savine, publishing the aforementioned works under the name of Louis Martin when he knew that the author was called Léon Aubry, is guilty of the same tort, and incurs the same responsibilities; he vainly argues that his role was limited to copying and putting on sale the incriminating works; it is apparent from an examination of agreements concluded between Aubry and he that he edited the above books, the covers of which list: “Savine, publisher,” and that the contract by him allegedly refers only to five hundred unsold copies of a previous edition of England and Freemasonry, by a Mr. Grazillier;

Whereas, therefore, we advise, as will be made in the formal judgment on the termination of this proceeding, Louis Martin complains rightly;

Whereas, for the determination of damages, the Court must consider the fact that the theft committed has led to justifiable confusion between the real Louis Martin and the usurper of his name, and resulted in attributing to him the authorship of works designed in a totally different spirit than the works of which he is the author; the Court has the necessary elements to assess that damage to amount of five hundred francs; and that it is necessary to jointly condemn Savine and Aubry, the payment of that sum by reason of the indivisibility of the offense committed;

As for the warranty or guarantee brought by Savine against Aubry:

Whereas Savine having personally associated with the almost criminal acts of Aubry, is not entitled to act as collateral against him;

As for the action in warranty brought by Aubry against Savine:

Whereas this cannot be accepted, for the same reason; Aubry vainly alleges that it is the actions of Savine which have made it impossible to change his pseudonym on both incriminating books; but this does not prove that he regularly put Savine on notice to change his alias or stop the sale of the works in question; that the two letters of 6 and 15 March, 1896, and the proceedings which followed against Savine before the Commercial Court are unrelated to the current debates; that, moreover, if, in his letter of 6 March, of which it is only known that he spoke of the copies which he had produced, Savine’s press sent him all unsold copies, in total 15, he no longer asked that he make available 200 copies of The Englishman Is Jewish?

Whereas, finally, he has not exercised the option, by which Savine could strip his name, and insert, as requested by Louis Martin, corrective articles in newspapers;

In terms of Aubry’s claim, seeking that the Court reject the correspondence between Louis Martin and Aubry, and condemn Louis Martin to pay him 10,000 francs in damages for trying to introduce this correspondence into the proceedings;

Whereas these claims were abandoned at the hearing and are, moreover, unfounded;

For these reasons;

We prohibit Louis (sic) Aubry and Savine from editing and selling in the future, under the name of Louis Martin, the books entitled: England and Freemasonry and The Englishman Is Jewish?

We now award damages at a rate of 25 francs for each copy of the said works put up for sale under that name; and for compensation for the damage already caused, we award in total 500 francs of damages.

We declare Louis Martin ill-founded in the rest of his claims, which we dismiss.

We declare Aubry ill-founded in his claims against Louis Martin, which we dismiss.

We declare Léon Aubry and Savine respectively ill-founded in their claims and guarantees, etc.

“Jurisprudence de la Presse,” Le Bulletin de la Presse, January 25, 1897, 11-12.

Notice to L’ANGLETERRE by Louis Marthin-Chagny (1896)

Notice

We now replace the name of Louis Martin on the cover of England and Freemasonry (English Mores) and The Englishman Is Jewish? (English Mores) with that of Louis Marthin-Chagny, to avoid any confusion that might arise between us and other writers signing the same name, including Mr. Louis Martin, author of Freemasonry: The Enemy of France (Delhomme and Briguet), Louis Martin, author of The Marshal Canrobert (Lavauzelle) ..., etc.

We do this in the common interest.

Source: Louis Marthin-Chagny, L’Angleterre (Paris: Chamuel, 1896).

We do this in the common interest.

Source: Louis Marthin-Chagny, L’Angleterre (Paris: Chamuel, 1896).

MARTIN VS. MARTIN

A Paris Trial

Paris, 8 January

Parisian newspapers are carrying an account of a civil trial: Louis Martin v. Louis Martin, some of the details of which are bound to stir up interest.

The claimant, M. Aubry, a man of letters, had published various books against Freemasonry under the pseudonym of Louis Martin, when suddenly there emerged out of the shadows a real Louis Martin, a man of letters as well, but a Freemason; and he sued the false Louis Martin for 10,000 francs in damages for usurping his name.

It is clear why the publication of the books against the Masonry should attract from a Mason disagreements without number. His brothers had treated him simply as a renegade. Two especially, one an “explorer close to the Belgian government,” and the other “the founder of the Mediterranean Union for the Greek-Slav alliance, formed by the friends of peace,” became red with anger and could have spared the alleged renegade their contempt.

These things are rough. It was all the more painful for the real Louis Martin that he became the author of two works infamous among his friends: The Error of Joan of Arc and The Gospels without God. These books have not penetrated to the general public, and yet it is not for lack of proposing original ideas. One concludes that “Joan of Arc was fatal to France because it would have been better if we had for a king the king of England.” Joan of Arc fatal to France! If that were true, we would know, and you would say with MacMahou, Ah well! There is someone who knows: It is Mr. Naquet; he found Mr. Louis Martin’s pamphlet quite good:

“What a pity,” wrote the apostle of divorce, “that Joan of Arc existed: for without her, united with the British, we would have been a great people! But let yourself appreciate this, because, in the slander of Boulangism, I am accused of a lack of patriotism, while I am very patriotic!”

The approval of Mr. Naquet is good. But in The Gospels without God, Louis Martin picked up the cup that everyone has taken down, for that matter: the letter from Victor Hugo. We know that at the end of his life Victor Hugo filled raving epistles to all the young poets and prose writers who were willing to honor their trust. The tone and style were that of a prophet: “My dear friend,” he said, or nearly so, “wearing the sign of the elect I am the night and you are the dawn. My shadow salutes your sun, etc. …” Mr. Louis Martin had his account:

“That man who wrote these heartfelt lines come to me!” Hugo wrote. “I will stretch out my hand.”

When Victor Hugo offers you his hand, you do not tighten up about a mere scribbler who usurped your name, a name hallowed by the blessing of a demigod!

Mr. Aubry, the fake Louis Martin, argued in his defense that the name of Martin belongs to everyone, even to jackasses. It is such a common name that it falls into the public domain. At the same address as the plaintiff, there is a Martin: he is not a mason or a philosopher but a milliner. Vapereau’s dictionary of contemporary illustrations mentions a Louis Martin, but that one is not the author of The Error of Joan of Arc, or The Gospels without God, but is the general of the Jesuits.

It is a fact that taking the pseudonym Martin, when one is a historian (provided we do not add the name of Henri), is not a criminal offense. However, the court has nonetheless levied against Mr. Aubry 500 francs in damages to the real Louis Martin, for theft of a name, as widespread as it is, because it was not his.

Source: Le Reveil, January 22, 1897, 816.

Parisian newspapers are carrying an account of a civil trial: Louis Martin v. Louis Martin, some of the details of which are bound to stir up interest.

The claimant, M. Aubry, a man of letters, had published various books against Freemasonry under the pseudonym of Louis Martin, when suddenly there emerged out of the shadows a real Louis Martin, a man of letters as well, but a Freemason; and he sued the false Louis Martin for 10,000 francs in damages for usurping his name.

It is clear why the publication of the books against the Masonry should attract from a Mason disagreements without number. His brothers had treated him simply as a renegade. Two especially, one an “explorer close to the Belgian government,” and the other “the founder of the Mediterranean Union for the Greek-Slav alliance, formed by the friends of peace,” became red with anger and could have spared the alleged renegade their contempt.

These things are rough. It was all the more painful for the real Louis Martin that he became the author of two works infamous among his friends: The Error of Joan of Arc and The Gospels without God. These books have not penetrated to the general public, and yet it is not for lack of proposing original ideas. One concludes that “Joan of Arc was fatal to France because it would have been better if we had for a king the king of England.” Joan of Arc fatal to France! If that were true, we would know, and you would say with MacMahou, Ah well! There is someone who knows: It is Mr. Naquet; he found Mr. Louis Martin’s pamphlet quite good:

“What a pity,” wrote the apostle of divorce, “that Joan of Arc existed: for without her, united with the British, we would have been a great people! But let yourself appreciate this, because, in the slander of Boulangism, I am accused of a lack of patriotism, while I am very patriotic!”

The approval of Mr. Naquet is good. But in The Gospels without God, Louis Martin picked up the cup that everyone has taken down, for that matter: the letter from Victor Hugo. We know that at the end of his life Victor Hugo filled raving epistles to all the young poets and prose writers who were willing to honor their trust. The tone and style were that of a prophet: “My dear friend,” he said, or nearly so, “wearing the sign of the elect I am the night and you are the dawn. My shadow salutes your sun, etc. …” Mr. Louis Martin had his account:

“That man who wrote these heartfelt lines come to me!” Hugo wrote. “I will stretch out my hand.”

When Victor Hugo offers you his hand, you do not tighten up about a mere scribbler who usurped your name, a name hallowed by the blessing of a demigod!

Mr. Aubry, the fake Louis Martin, argued in his defense that the name of Martin belongs to everyone, even to jackasses. It is such a common name that it falls into the public domain. At the same address as the plaintiff, there is a Martin: he is not a mason or a philosopher but a milliner. Vapereau’s dictionary of contemporary illustrations mentions a Louis Martin, but that one is not the author of The Error of Joan of Arc, or The Gospels without God, but is the general of the Jesuits.

It is a fact that taking the pseudonym Martin, when one is a historian (provided we do not add the name of Henri), is not a criminal offense. However, the court has nonetheless levied against Mr. Aubry 500 francs in damages to the real Louis Martin, for theft of a name, as widespread as it is, because it was not his.

Source: Le Reveil, January 22, 1897, 816.

From a Letter of Louis Martin (January 12, 1901)

Mr. Louis Martin, the deputy from the Var, does us the honor of addressing to us the following letter:

Mr. Director,

There was a communication about me on January 7 in The Intermediary between Researchers and the Curious, in which one of your readers asked the following questions:

1. Who is the Louis Martin who wrote the booklet The Error of Joan of Arc? 2. Is he the first to have supported the paradoxical idea which is the basis for his book? 3. Is this Mr. Louis Martin the deputy who was recently elected?

On this last point, let me tell you that there is an absolute identity of first and last name between the author of the work referenced and the new member from the Var, though I am diametrically opposed to that of my namesake in opinion regarding the good Maid of Lorraine, “whom the English burnt at Rouen,” as said our old Villon.

The Louis Martin, author of the book which concerned your correspondent, is another [of my name], and if I am not mistaken, the writer whose death the newspapers announced seven or eight months ago had published various books of religious philosophy and Masonic propaganda, the Gospels without God, the Freemasonry, etc. […]

Source: “Une opinion sur Jeanne d’Arc,” L’Intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux, January 22, 1901, 98-99.

Mr. Director,

There was a communication about me on January 7 in The Intermediary between Researchers and the Curious, in which one of your readers asked the following questions:

1. Who is the Louis Martin who wrote the booklet The Error of Joan of Arc? 2. Is he the first to have supported the paradoxical idea which is the basis for his book? 3. Is this Mr. Louis Martin the deputy who was recently elected?

On this last point, let me tell you that there is an absolute identity of first and last name between the author of the work referenced and the new member from the Var, though I am diametrically opposed to that of my namesake in opinion regarding the good Maid of Lorraine, “whom the English burnt at Rouen,” as said our old Villon.

The Louis Martin, author of the book which concerned your correspondent, is another [of my name], and if I am not mistaken, the writer whose death the newspapers announced seven or eight months ago had published various books of religious philosophy and Masonic propaganda, the Gospels without God, the Freemasonry, etc. […]

Source: “Une opinion sur Jeanne d’Arc,” L’Intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux, January 22, 1901, 98-99.