M. A. Murray

1924

|

NOTE |

Margaret Alice Murray (1863-1963) was an Anglo-Indian Egyptologist and folklorist best known as the author of The Witch-Cult in Western Europe, a highly influential though incorrect assessment of the survival of pagan rites among medieval and early modern women. As an Egyptologist, Murray conducted pioneering research, working alongside Flinders Peterie down to the outbreak of the First World War. The article below examines the medieval Arabic transmission of pharaonic history and how errors by copyists gradually transformed the Egyptian history of Manetho into the version known from Arabic historians such as al-Maqrizi and the author of the Akhbar al-zaman. This article first appeared in the journal Ancient Egypt in 1924. Some parenthetical Arabic text has been omitted.

|

MAQRIZI’S NAMES OF THE PHARAOHS.

Some years ago Prof. Petrie suggested to me that a fruitful field of investigation might be found in the study of the Arabic names of the Pharaohs. These names are no more distorted in Arabic than they are in Greek, and therefore a certain number of identifications are possible. It is also evident that tradition has preserved certain incidents and events otherwise unrecorded. In this paper I take only Maqrizi’s account as given in his chapters on the cities of Amsus and Memphis, Amsus being the ancient name of Masr or Cairo.

The Kings of Memphis begin with Beïsar, son of Ham, son of Noah; the genealogy then continues, in the same way as in Genesis x, with tribal, not personal, names. Maqrizi quotes various authorities who differ slightly in the order of the tribes, but they all agree on the one point, which is that the earliest personal name is Tudras, son of Sa. The genealogy, as quoted from Ibn Abd el Hakim, gives Masr, son of Beïsar, then in succession the four sons of Masr—Quft, Ashmoun, Atrib, and Sa. These names show clearly that up to this point we are dealing with tribes or cities, therefore Tudras ben Sa must be Tudras the Saite. This suggests that according to tradition the Kings of Memphis came from the Delta.

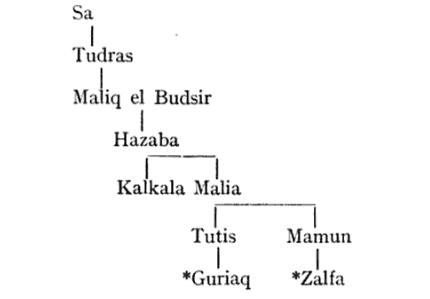

The most consecutive genealogy given by Maqrizi himself, and also quoted from Ibn Abd el Hakim, represents, perhaps, a Saite dynasty, and is as follows:--

The Kings of Memphis begin with Beïsar, son of Ham, son of Noah; the genealogy then continues, in the same way as in Genesis x, with tribal, not personal, names. Maqrizi quotes various authorities who differ slightly in the order of the tribes, but they all agree on the one point, which is that the earliest personal name is Tudras, son of Sa. The genealogy, as quoted from Ibn Abd el Hakim, gives Masr, son of Beïsar, then in succession the four sons of Masr—Quft, Ashmoun, Atrib, and Sa. These names show clearly that up to this point we are dealing with tribes or cities, therefore Tudras ben Sa must be Tudras the Saite. This suggests that according to tradition the Kings of Memphis came from the Delta.

The most consecutive genealogy given by Maqrizi himself, and also quoted from Ibn Abd el Hakim, represents, perhaps, a Saite dynasty, and is as follows:--

In the reign of Zalfa the Amalekites (Hyksos?) entered and conquered Egypt after a series of battles, the Egyptian queen retreating further and further south, until she reached Kus, where she committed suicide rather than fall into the hands of her enemies.

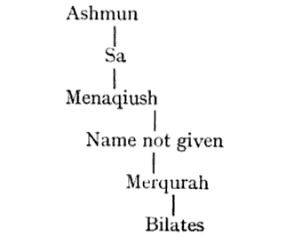

Another genealogy appears to represent the Kings of Ashmun:—

Another genealogy appears to represent the Kings of Ashmun:—

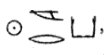

The termination sh which occurs so often in Maqrizi’s names suggests a foreign, probably Greek, source of information. Both Menaqiush and Merqurah suggest Egyptian names, the latter might very well be derived from

a name of a king in the XIIIth dynasty. It might, however, be a distorted form of

Merqurah was, according to Maqrizi, a wise magician. He built cities, founded temples, and raised statues. At his death he was buried in the western desert with rich magnificence.

Bilates, the son of Merqurah, was a child at his father’s death, and the kingdom was governed by his mother, whose name, unfortunately, is not preserved. She is said to have been a capable and just ruler, who gained the affection of her subjects by lowering taxes. When Bilates reached manhood he left the administration in her hands, and amused himself with hunting. After a reign of thirteen years he died of small-pox and the succession passed to his uncles. As Maqrizi calls these uncles Atrib and Sa, it is evident that they are each the beginning of a new genealogy of Athribis and Sais respectively. The account of Merqurah and Bilates gives a reasonable and unexaggerated summary of two reigns, of which the last may possibly be identified. There is at least a resemblance between Bilates and Thothmes II, the weak young king whose energetic and capable queen administered the kingdom. The marks on the skin of the mummy of Thothmes II may have been caused by the same malady of which Bilates is said to have died. There is, however, no possibility of deriving the name Bilates from any of the names of Thothmes II; therefore, though the tradition may point to Hatshepsut and Thothmes II, the name must be sought elsewhere. The Bilates of Maqrizi is one of the earliest kings of history, and I would suggest that the name is identical with that of a Pharaoh of the IInd dynasty

Bilates, the son of Merqurah, was a child at his father’s death, and the kingdom was governed by his mother, whose name, unfortunately, is not preserved. She is said to have been a capable and just ruler, who gained the affection of her subjects by lowering taxes. When Bilates reached manhood he left the administration in her hands, and amused himself with hunting. After a reign of thirteen years he died of small-pox and the succession passed to his uncles. As Maqrizi calls these uncles Atrib and Sa, it is evident that they are each the beginning of a new genealogy of Athribis and Sais respectively. The account of Merqurah and Bilates gives a reasonable and unexaggerated summary of two reigns, of which the last may possibly be identified. There is at least a resemblance between Bilates and Thothmes II, the weak young king whose energetic and capable queen administered the kingdom. The marks on the skin of the mummy of Thothmes II may have been caused by the same malady of which Bilates is said to have died. There is, however, no possibility of deriving the name Bilates from any of the names of Thothmes II; therefore, though the tradition may point to Hatshepsut and Thothmes II, the name must be sought elsewhere. The Bilates of Maqrizi is one of the earliest kings of history, and I would suggest that the name is identical with that of a Pharaoh of the IInd dynasty

The reading presents only one difficulty, the final n; with that exception, the name Per-hati-s passes easily into Bilâtes. The question whether the n is essential to the meaning of the phrase cannot be certain until that meaning is known. If it is merely the indirect genitive, as in Senusert, the name could be written either with or without the n.

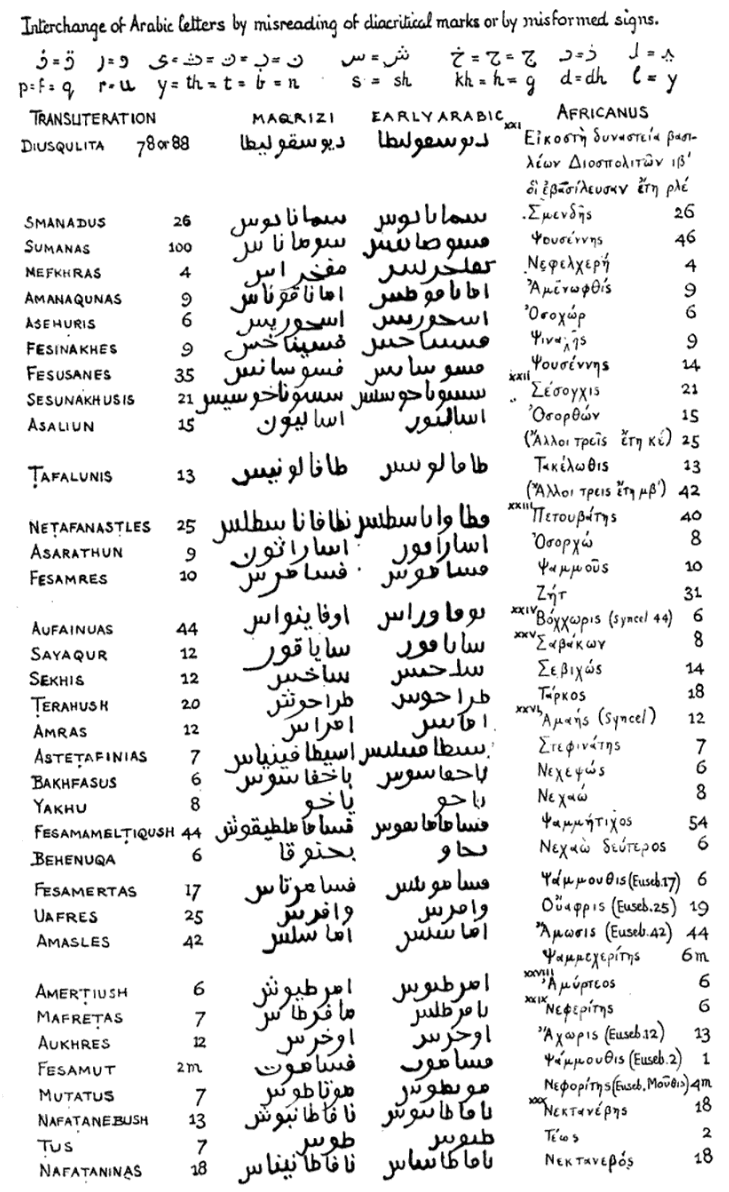

The Athribis genealogy is very short:--

The Athribis genealogy is very short:--

This Athribis is clearly in the Delta, for Qlimun is said to have built both Tennis and Damietta. As the kingdom reverted to Sa ben Qubtim, it would seem that Sais absorbed Athribis.

The most consecutive genealogy of the Saite kings has been given above.

The most consecutive genealogy of the Saite kings has been given above.

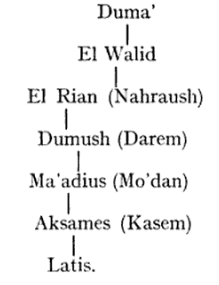

The Amalekite kings, who may represent the Hyksos, are as follows (the names in brackets being variants):--

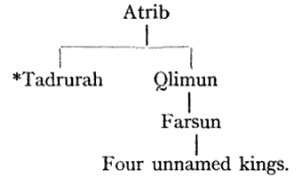

These are not identifiable, and are followed by the “Pharaoh of Moses,” whose genealogy is given with great particularity back to Shem and Noah, notwithstanding the fact that he is said to be a slave and an Egyptian. After him come a number of kings and queens without any order, until we reach solid ground with the XXIst dynasty. The names of these kings are said to be Greek (Rumi), and it is fairly certain that they are copied from Manetho, though the variants show that it was not from a known list. The Arabic writing has so distorted the spelling that many names are almost unrecognisable, and it is only by carefully observing the possible mistakes which can be made by misreading certain letters that many names, which at first sight appear a mere jumble, are found to be fairly accurate transcriptions of the Greek. One or two points are noticeable. The dynasties are not divided, the names of the kings running on consecutively. The Persians are omitted completely, Amyrtaeus of the XXVIIIth dynasty follows directly after Amasis II, and he and his four successors are said to be Babylonian, while Nectanebo I and his two successors are called Assyrian. “The Kingdom then passed to Alexander, son of Philip the Greek.” The variation in the lengths of reigns cannot, I think, be accounted for by misreadings or by mistakes in copying. The MS. from which this list is taken is therefore not the same as those copied by Africanus or Eusebius. For comparison with the Arabic I have given Africanus’ list, with the variations from Eusebius and Syncellus where they agree with, and Africanus differs from, the Arabic, both in names and lengths of reigns. In Africanus there appears at the end of the XXIIIrd dynasty a king called Zet, with a reign of 31 years: this king does not appear in the later copyists, nor in Maqrizi, who passes directly from Fsamûs (Fasameres) to Aufaïnuas. Prof. Petrie has suggested (ANCIENT EGYPT, 1914, p. 32) that Zet means only a doubtful quantity, which is unassigned. The reign of Aufaïnuas, whom I equate with Bocchoris, is given by Maqrizi as 44 years: this agrees with Eusebius and Syncellus, but not with Africanus; in short, Maqrizi’s dates agree usually with Eusebius when they differ from those of Africanus. This, however, is not the case at the end of the list. Africanus ends the XXIXth dynasts with Psammuthis 1 year, Nephorites 4 months; Eusebius gives Psammuthes 1 year, Muthes 1 year, Nepherites 4 months; Maqrizi differs from both, Fsamut 2 months, Mutatus 7 years. The dates of the XXXth dynasty differ in all three lists, but Maqrizi keeps closer to Africanus than to Eusebius, for his total is 38 years for the whole dynasty, which is the same as Africanus. The reigns of Nafatanebush (Nectanebo I) and Tus are given respectively as 13 and 7 years, making 20 years for the two kings. Africanus has the same length of time but divides it differently, giving 18 years to Nectanebo and 2 years to Teos.

It seems then, that Maqrizi, though he lived as late as the fifteenth century, had access to some list of kings which has not survived; a list which had been unintelligently copied, as witness the Diospolites of the XXth dynasty, transformed into a king called Diusqulita, but which is obviously the whole of the third book of Manetho.

It is possible that some of the earlier Arab historians who wrote on Egypt may also have recorded historical facts which would be worth investigating.

It seems then, that Maqrizi, though he lived as late as the fifteenth century, had access to some list of kings which has not survived; a list which had been unintelligently copied, as witness the Diospolites of the XXth dynasty, transformed into a king called Diusqulita, but which is obviously the whole of the third book of Manetho.

It is possible that some of the earlier Arab historians who wrote on Egypt may also have recorded historical facts which would be worth investigating.

Source: M. A. Murray, “Maqrizi’s Names of the Pharaohs,” Ancient Egypt (June 1924, Part II), 51-55.