|

I hate zombies. I'm sorry. I tried to like them, but I find zombies to be among the least imaginative, dullest horror monsters. And it really bothers me that zombies are apparently now an almost $6 billion business (calculated over several years), making them more important to the economy than hip hop music ($1 billion annually) and fake college degrees ($1 billion annually--go figure), but less important than pornography ($13 billion annually). Zombies are even giving vampires a run for their money. The bloodsuckers are responsible for more than $7 billion in Hollywood profits alone since 2009, though mostly due to the Twilight movies.

The modern zombie emerged from an accident of entertainment industry economics. George Romero really like Richard Matheson's I Am Legend but couldn't afford to pay him to adapt the novel about hordes of marauding vampires. So, he changed the vampires from bloodsuckers to general-issue, undead cannibal "ghouls," and he made them not just pallid and sickly but rotten, closer to the European folkloric revenant from which the vampire had sprung two centuries earlier. But in doing so, Romero demystified the undead, taking away the traditional association of resurrected corpses with magic, the occult, and even religious power. Earlier walking corpses had a moral and magical dimension. The ghost existed to right past wrong and to provide proof of the survival of the soul after death. Frankenstein's monster raised Promethean questions about the human desire to become god. The vampire had a fascinating glamor, not only of eternal life but also of the vast weight of history that sat heavily upon his or her immortal shoulders. Count Dracula, especially, captured the mystical and occult dimension of the undead. Not only could he transform into mist and wolf, but he also attended the devil's school, the Scholomance. When he comes to Renfield at Dr. Seward's asylum, he speaks in the words of the Devil. In Dracula, the Count says: "All these lives will I give you, ay, and many more and greater, through countless ages, if you will fall down and worship me!" Compare Mark 4:9, where the Devil says to Jesus: "All these things will I give thee, if thou wilt fall down and worship me." The best horror monsters combine terror with awe, existing in the dark place that leads toward a contemplation of the Burkean sublime. The Cthulhu Mythos is a perfect example of horror that builds toward transcendent experiences of the sublime. The terror of alien beings from the darkest cosmos serves a higher purpose, frightening the mind into an understanding of the vast, awesome universe surrounding us. But even traditional horror figures--the ghost, the vampire, the werewolf, the mummy (which is, really, a zombie with a brain), etc.--offer a taste of the sublime when set in their traditional Gothic framework of dark nights, crumbling architecture, a vast spaces. The zombie is neither a magical figure, an occult figure, or a representative of the Burkean sublime. The zombie is no latter-day remainder of the mythological world view, no avatar of forgotten ages when other gods ruled the human mind. The zombie is a thoroughly modern monster, or rather not much of a monster at all. It is simply a body, reanimated, without mind. Even Victor Frankenstein would be unimpressed. His resurrected corpse read Milton. Absent all three traditional trappings of horror monsters--the Gothic, the occult, and the sublime--zombies are, like so many things in the modern world, hollow, plastic shells--poor simulacra of older, better monsters they have imperfectly replaced.

2 Comments

Caution: This post contains sexually suggestive early twentieth century imagery.

Recently, I've discussed the way pagan beliefs were given a Satanic cast by Christians, who turned pagan worship ceremonies into Black Masses full of sodomy and blasphemy. In 1862, Jules Michelet tried to paint a more sympathetic (if inaccurate) portrait of medieval witches by describing their faith as a pagan-influenced feminist rebellion against Catholic patriarchy. His book, La Sorcière, is known in English as Satanism and Witchcraft, and of course the weird art used to illustrate the 1911 printing of the book is something to behold. In tomorrow's Albany, N.Y. Times-Union (not yet online), book critic Donna Liquori talks about Bram Stoker's novel Dracula and its importance in establishing the vampire as a figure of terror. So far, so good. But in recommending the Victorian novel for Halloween, Liquori reassured her readers that Dracula is "surprisingly easy to read." I'm not sure if I am more annoyed that Liquori assumes readers of a book column would be put off by difficult literature, or that she presumes that older work are inherently difficult compared to today's easy-reading pop trash.

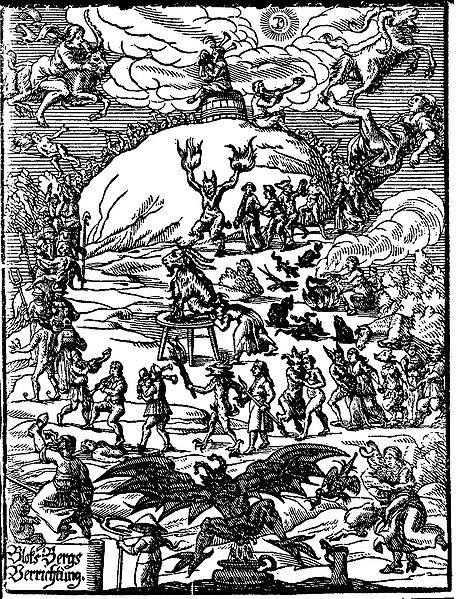

On the complete opposite end of the spectrum, in the New York Times, Glen Duncan imagines a slavering mass of idiot horror readers against which he can take arms. Here is how he imagines a typical American consumer (of course not you, gentle New York Times reader) will react to literary novelist Colson Whitehead's zombie novel, Zone One: I can see the disgruntled reviews on Amazon already: “I don’t get it. This book’s supposed to be about zombies, but the author spends pages and pages talking about all this other stuff I’m not interested in.” Broad-spectrum marketing will attract readers for whom having to look up “cathected” or “brisant” isn’t just an irritant but a moral affront. These readers will huff and writhe and swear their way through (if they make it through) and feel betrayed and outraged and migrained. Nice to know that a man with eight novels under his belt--including the genre novel The Last Werewolf (2011)--has such faith in readers. Who, incidentally, does he think buys his books? Aesthetes only? Good luck making money that way. Note, incidentally, that these are not actual readers but illiterate straw men concocted solely for the purpose of tarring readers of horror as something less than literate. I have no doubt that some Amazon customer reviews will be nasty and barely coherent; but this is true for cat food, DVDs, and flannel sheets as much as any book. It's hard to imagine that in the age when Dracula was written, the horror genre had not yet been cut loose from mainstream literature (1930s pulp magazines would see to that), and horror was not just a respectable mode of literature, but one practiced from time to time by the very best writers--Charles Dickens, Henry James, Edith Wharton, etc. Now, apparently, so thoroughly did the publishing industry subdivide genres and markets, it is apparently tremendous news when a horror novel is not mindless, or when a genre lover finds a classic to be comprehensible. We might as well just give up on books altogether. With Halloween just days away, I thought I'd share another installment in my Weird Old Art series. This image depicts a "witches' sabbath" in which devils and demons frolic with sorcerers and sorceresses around a hill at midnight. It should take no terribly practiced eye to see that the event depicted here by Johannes Praetorius in 1668 is little more than a latter-day survival of the old pagan worship ceremonies, diabolized by Christians who saw all manner of rude and profane acts (note the scatological demon in the foreground) in what must have originated as pagan rites carried out by torchlight around sacred hills. And yes, that woman is doing what you think she is to the goat at center.

Ancient Aliens tried to claim that the undead were not “mere myths” but aliens in the episode “Aliens and the Undead.” Sadly, however, the first half hour did not focus on vampires and zombies as promised but instead went the more prosaic route of exploring whether Egyptian mummies had a relationship to alien cryogenic body preservation technology, and whether afterlife deities were actually extraterrestrials.

Much hay was made from the odd shape in the depiction of the heads of the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaton and his family, arguing that this was an imitation of alien skulls. Similar skulls, the program notes, are found in Peru, but such deformations are rather easy to produce with infant head-binding. There is no particular reason to imagine a connection between Egypt and Peru, much less an extraterrestrial one. While the program claims "only" the alien-influenced cultures of Peru and Egypt practiced cranial deformation, in fact Neanderthals did it 45,000 years ago, as did early human cultures of the Neolithic and historically-documented groups in Australia, the Pacific Islands, North America, and late Antique Europe (the Huns and Alans, and the Germanic peoples they influenced). So, chalk one up to another flat-out Ancient Aliens lie. Then, halfway through, we finally got to the vampires. But of course Ancient Aliens managed to muck it up by conflating vampires with vengeful spirits and blood-sucking demons and then calling all of them “extraterrestrials abandoned here on earth.” Because aliens apparently like to suck blood (“cosmic fuel,” the narrator said) since, you know, creatures from another world clearly evolved to survive on the blood of mammals. (Funny, I thought the aliens ate gold, as per Laurence Gardner, building on Zecharia Sitchin.) But no! Minutes later it isn’t that aliens are eating the blood. Instead, the “theory” is now that human blood loss leads to altered states of consciousness that open human minds to extraterrestrial worlds through some kind of quantum window. Or, as David Hatcher Childress claims, ritual bloodletting, as in Mayan rituals, is merely the aliens’ way of showing us “how important” our blood is. As opposed, apparently, to spinal fluid or various internal organs. The program wonders what it takes to bring a dead person back to life (other than, of course, CPR, or, today, a defibrillator). Childress, stupidly, states: “What kind of powers would you have to have to do that? The powers of an extraterrestrial?” No, just a lifeguard. Remember, this man spent the last three decades vehemently arguing that he was not an ancient astronaut theorist. Now he talks of how the aliens will shepherd our souls to the stars after death. Ancient Aliens speculates that the “aliens” exist on a separate plane from us, and our souls will move to that space after death, where we will rejoin the aliens in a cosmic paradise. At some point these aliens stopped having any meaningful distinction from the gods they were originally proposed to replace. At this point, we might as well give up the concept of “ancient aliens” altogether and admit that the ancient astronaut theorists just want the pagan gods to be real so they can give them magic gifts. I turns out I was wrong about the passage from the Epic of Gilgamesh used in the History Channel documentary on the history of zombies. The passage they used was 6.99-100, in which Ishtar (Inanna) threatens to unleash chaos:

I will raise up the dead, and they will devour the living, I will make the dead outnumber the living! (trans. Jeffrey H. Tagay) These two lines are heralded as the world's first "zombie apocalypse," but this is only true if one takes them out of context and applies a hefty dose of imagination. The lines in question were adapted for the Gilgamesh epic from an older poem, known as Nergal and Ereshkigal (5.11-12, and again at 26-27), where it is found verbatim, spoken by Ereshkigal, the Queen of the Dead, as a curse. The Mesopotamian dead, however, were not zombie corpses but rather, as the Gilgamesh epic (tablet XII) shows, as cold, lonely souls imagined as dust-eating birds: [I was taken] to the house, whose inhabitants are deprived of light; to the place where dust is their sustenance, their food clay. They are clothed, like a bird, with feathered raiment. Further, we know from Mesopotamian spell tablets that they believed in ghosts and feared risen spirits, implying that the dead were believed to take spiritual, not corporeal form. Thus, the released dead of Gilgamesh 6.99-100 and Ereshkigal 5.11-12 are ravenous ghosts, not actual bodies, who will consume the living. At any rate, this was a mere threat, never enacted, though interestingly in another poem about Inanna's descent into the underworld, demons from the underworld do rise to rend and tear her lover Dumuzi to shreds and drag his soul underground. Tonight the History Channel (I'm still not able to bring myself to call it simply "History") presents a history of zombies from the Sumerians to today. According to the program description for Zombies: A Living History, the program will explore the appearance of zombies in the Epic of Gilgamesh. I'm not sure what to think of that.

I presume the program will refer to Tablet XII of Gilgamesh, in which Enkidu visits the underworld and returns to the living world. This Babylonian tablet, which translates an earlier Akkadian poem is seen by most scholars as an appendix added to the original epic at a later date, since it varies enormously from the rest of the poem. For starters, Enkidu had been killed off back in Tablet VII, so having him alive again is a good indication that this was originally a separate poem. At any rate, if a catabasis, or a descent to the underworld, is all it takes to be a "zombie," then Orpheus, Heracles, Theseus, and Odysseus must all be zombies, too. Needless to say, these Antique figures do not meet the modern definition of a reanimated, mindless corpse--a definition which descends, incidentally, not from the Classical catabasis but instead from the same source as the modern vampire, from the folkloric revenant or wraith, a corpse that rises from the grave to feed on the living. One claim alternative historians have made from the eighteenth century down to today is that the Greek Neoplatonist philosopher Proclus claimed in his commentary on Plato's Timaeus that the Great Pyramid of Egypt had a flat top from which the priests of Egypt observed the stars and recorded the rising and setting of the star Sirius. This claim apparently first appeared in John Greaves' Pyramidographia (1646), in which he writes: "Upon this flat [top], if we assent to the opinion of Proclus, it may be supposed that the Aegyptian Priests made their observations in Astronomy; and that from hence, or near this place they discovered, by the rising of Sirius the [Sothic cycle]" (1737 edition; pp. 99-100). His source, he said, was book 1 of Proclus' commentary on Timaeus, but nothing more specific.

The claim was then picked up by many (if not most) writers on the pyramids down to Richard Anthony Proctor, who used this single line of Proclus to argue for the Great Pyramid's astronomical function in several books of the 1870s and 1880s. He did not, however, provide a reference for Proclus. This has not stopped modern writers from John Anthony West to Alan Alford to Robert Bauval to Graham Hancock from quoting or citing Proctor's assertion, derived apparently from Greaves, that Proclus had declared the pyramid an observatory. All of these writers use this assertion in their works, and none quotes Proclus directly--only Proctor. I have never read the specific words of Proclus on this subject. I have tried to track down the exact words of Proclus, and I have not been able to do so. I have scanned both a 19th century and 2007 translation of Proclus' commentary on Timaeus, and there does not appear to be any reference to the Egyptian pyramids in it. Nor did I find a reference to Sirius, or even much about astronomy. The closest I found in the Timaeus commentary, book 1, is when Proclus writes the following of the priests: "they survey without impediment the celestial bodies, through the purity of the air, and preserve ancient memorials, in consequence of not being destroyed either by water or fire." I am frankly stumped. If anyone knows where this reference came from, outside of Greaves' imagination, I would be appreciative if you could leave a note in the comments. A while back ancient astronaut theorist Giorgio Tsoukalos cited Al-Maqrizi's fifteenth-century Al-Khitat as evidence that aliens oversaw the building of the Egyptian pyramids four thousand years earlier. Unfortunately, I don't speak medieval Arabic, so I wasn't able to comment on Maqrizi's specific language. Today I finally stumbled upon a partial translation of his discussion of the pyramids of Egypt, and I thought I would share it with you:

After him [Shahlûk] reigned his son Surid. He was an excellently wise man; and he was the first who levied taxes in Egypt, and the first who ordered an expenditure from his treasuries for the sick and the palsied, and the first who instituted the observation (?) of daybreak. He made wonderful things; among which was a mirror of mixed metal, in which he would observe the countries, and know in it the occurrences that happened, and what was abundant in them, and what was scarce. He placed this mirror in the midst of the city of Amsûs [the antediluvian capital of Egypt], and it was of copper. He made also in Amsûs the image of a sitting female mining a child in her lap. * * * That image remained until the Flood destroyed it: but in the books of the Copts [it is said] that it was found after the Flood, and that the greater part of the people worshipped it. * * * This Surid was he who built the two greatest Pyramids in Egypt, which are ascribed [also] to Sheddâd, the son of Ad; but the Copts deny that the Adites entered their country by reason of the power of their magic. When Surid died he was buried in the Pyramid, and with him his treasures. It is said that he was 300 years before the Flood, and that he reigned 190 years. After him reigned his son Harjîb; he was excellently wise, like his father, in the knowledge of magic and talismans. He made wonderful things, and extracted many metals, and promulgated the science of alchemy. He built the Pyramids of Dahshûr, conveyed to them great wealth, and choice jewels, and spices, and perfumes, and placed on them magicians to guard them. When he died he was buried in the Pyramid, and with him all his wealth and rarities. Source: “Bunsen’s Egypt and the Chronology of the Bible,” The Quarterly Review 105 (1859), 390-391. Well, there you have it. Case closed! But seriously, I can't see anything in this besides a medieval legend trying to wed the pyramids to the Islamic notion (shared by the Jews and Christians) of the antediluvian world. Actually, if I were an ancient astronaut theorist I'd be more interested in the idea of a "mirror of mixed metal" that lets someone see things happening in other regions--a prehistoric iPad! Since Halloween is right around the corner, I've posted a classic article on vampires for your reading enjoyment. Today's selection comes from the Cornell University archaeologist J. R. S. Sterrett, who in 1899 described his experiences encountering true-life belief in vampires in the rural areas of Greece. Read and enjoy!

|

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed