|

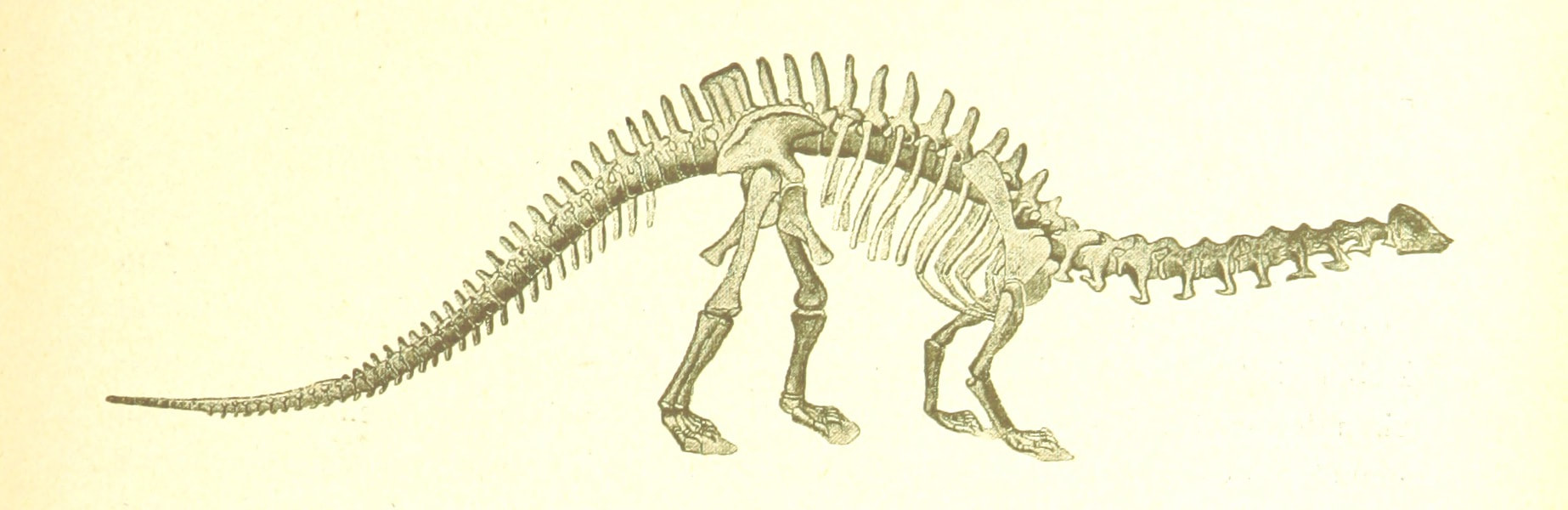

Today I am working on my All About History article on Hitler’s wonder weapons, so you are getting a rerun. This past week, Scientific American published a piece by Darren Naish exploring the origins of Mokèlé-mbèmbé, the legendary Congolese monster supposed by many cryptozoologists to be a living dinosaur. Nash correctly attributes the development of the myth to the dinosaur mania of the early twentieth century, the same impulse that led Conan Doyle to write The Lost World around the same time. But neither in the blog nor in his book Hunting Monsters (according to a text search in Google Books—I haven’t read the book) does Naish discuss the story that has long served as “evidence” that the monster predated twentieth century adventurers’ stories. Therefore, I present my discussion of the eighteenth century French account of Mokèlé-mbèmbé’s monstrous footprints. I originally wrote this in 2012, and the text below is the revised and expanded version presented in my 2013 book Faking History. A Dinosaur in the Congo? The zeal of Afrocentrists to find Africans around the world was quite obviously a response to the imperialist-colonialist zeal to disinherit indigenous peoples from their own history and to link native peoples the world over with the primitive and the wild. The alleged dinosaur living in the Congo Basin, mokèlé-mbèmbé, has appeared widely in popular culture, thanks in large part to early twentieth century writers who reported Congolese folklore about the creature and saw in it a reflection of the most primeval times of earth’s history. The earliest report for the supposed monster is almost universally claimed to be a passage in a 1776 book by the Abbé Liévin-Bonaventure Proyart (1743-1808), a French cleric and writer later executed for writing the wrong thing about Louis XVI during the reign of Napoleon. Proyart served as a missionary in the Congo Basin in the 1760s, and in an early chapter of his book on the region, Histoire de Loango, Kakongo, et autres royaumes d’Afrique (1776), he describes the animals of west and central Africa using reports compiled by fellow missionaries in the area. He devotes only two sentences to the monster later cryptozoology authors have claimed as a dinosaur. This creature is frequently said to be a sauropod on the order of Apatosaurus (Brontosaurus). These authors tend to selectively quote only a part of the first sentence, mostly because the second sentence makes plain that the “monster” is in no wise the equivalent of a dinosaur. They also tend to all abridge the exact same translation, first provided, so far as I can tell, in the journal Cryptozoology in 1982. (Seriously, does anyone in alternative studies actually review primary sources? I mean, if I can do it, it can’t be that hard…) Roy P. Mackal’s A Living Dinosaur: The Search for Mokele-Mbembe (1987) at least provided the correct measurements and a full, if not absolutely faithful, quotation. [1] By contrast, Michael Newton’s account in Hidden Animals (2009) is dependent upon Mackal (an acknowledged source) but garbles the discussion and claims Proyart described “tribal stories of a beast known as mokele-mbembe…,” [2] which he certainly did not do. Since this passage is almost never given in full and sometimes given incorrectly, allow me provide my own translation to clarify things: The Missionaries have observed, passing along a forest, the trail of an animal they have not seen but which must be monstrous: the marks of his claws were noted upon the earth, and these composed a footprint of about three feet in circumference. By observing the disposition of his footsteps, it was recognized that he was not running in his passage, and he carried his legs at the distance of seven to eight feet apart. [3] This monster, as you can see, is not terribly large by the standards of dinosaurs. Note, for example that my own footprint has a circumference of two feet (with sides of 11 inches, 4 inches, 7 inches, and 2 inches), and at 5’10” I am hardly a monstrously-sized human. By contrast, an Apatosaurus had a footprint measuring approximately ten feet in circumference (three feet by two feet in dimension), though other dinosaurs were obviously much smaller. Mackal recognized this, though minimizing the implications. He quotes a modern Franco-Belgian scientist, Bernard Heuvelmans, as suggesting the measurements are somewhat akin to the rhinoceros, though he argues that it cannot be one because rhinoceroses lack claws. [4] The trouble seems to be that modern writers are confusing circumference for length (they are not the same), and they have taken Proyart’s adjective monstrueux as an indication that he was referring to a “monster.” However, while monstrueux carries the implication of “horrific” or “monstrous” today, in the eighteenth century, the word carried instead the connotation of “prodigious,” or very large, according to French dictionaries published in that era; it is modern people who added terror to the older sense. [5] Proyart and his sources did not express any great terror at the creature, whose description he sandwiches between passages on the elephant and the lion, and the context of the passage clearly implies that he considered the creature simply one of many animals of similar bulk. A rhinoceros, for comparison, has a footprint averaging seven inches (18 cm) in diameter, according to zoologists, but which can easily top eleven inches (28 cm). This yields a circumference (using π times diameter) of two feet (56.5 cm) for an average rhino and our required three feet (91 cm) for the eleven-inch rhino foot. The rhinoceros also has a head-and-body length averaging around twelve feet (3.7 m), with a body length of about eight feet (2.4 m), meaning its legs are seven to eight feet (2.1-2.4 m) apart. The greatest objection to identifying Proyart’s monster as a rhinoceros is that the rhinoceros does not have claws. Its footprint, however, takes the appearance of three enormous, sometimes pointed, claw marks, which are actually its toes but appear distorted when smeared through mud. A hippopotamus is also a close fit, with a footprint that similarly resembles that described by Proyart, with what look like “claw” marks but are actually the toes. Keeping in mind that Proyart did not witness the tracks firsthand, this would seem to be a reasonable description of a rhinoceros or hippopotamus track. A second objection to identifying Proyart’s print as a hippopotamus or rhinoceros is the claim that such creatures do not currently live in the area of the Congo now home to the legend of mokèlé-mbèmbé. Proyart did not provide a location for his missionary friends’ sighting of the prints, so this objection cannot be sustained. There is no way to localize Proyart’s description to the same territory where the (current) mokèlé-mbèmbé myth is centered. Both the rhinoceros and the hippopotamus had ranges that included areas visited by missionaries when Proyart was active in Africa. The hippopotamus range included the Congo, and the rhinoceros the areas to the north. (Sadly, both have declined markedly since then and are no longer found in their historic ranges.) Most damning of all is the fact that Proyart does not describe either the hippopotamus or the rhinoceros in his book, meaning that he was probably not aware that the hippopotamus lived in sub-Saharan Africa. The rhinoceros, then known primarily from Asian species, would also have been beyond his knowledge in 1776. Since Proyart describes the monster in a passage listing elephants and lions, this would imply that the creature was probably not in the rainforest, perhaps making the rhinoceros the more likely animal. At any rate, given the measurements provided by Proyart and the secondhand nature of the report, it is not possible to infer the existence of a dinosaur from his description of relatively small footprints. Notes [1] Roy P. Mackal, A Living Dinosaur: The Search for Mokele-Mbembe (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1987), 2. Mackal paraphrases the second sentence somewhat for clarity, but his translation does not change the essential meaning.

[2] Michael Newton, Hidden Animals: A Field Guide to Batsquatch, Chupacabra, and Other Elusive Creatures (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2009), 44. [3] Les Missionnaires ont observé, en passant le long d’une forêt, la piste d’un animal qu’ils n’ont pas vu; mais qui doit être monstrueux: les traces de ses griffes s’appercevoient fur la terre, & y formoient une empreinte d’environ trois pieds de circonférence. En observant la disposition de ses pas, on a reconnu qu’il ne couroit pas dans cet endroit de son passage, & qu’il portoit ses pattes à la distance de sept à huit pieds les unes des autres. (Liévin-Bonaventure Proyart, Histoire de Loango, Kakongo, et autres royaumes d’Afrique [Paris, 1776], 38-39). [4] Mackal, A Living Dinosaur, 4-5. [5] Similarly, Dr. Johnson in his Dictionary of 1755 defined “monstrous” as being “unnatural, shocking.” Both the English and French words were drawing on the older Latin sense of monstrum, referencing an unnatural birth, a sign from God.

7 Comments

Joe Scales

6/13/2018 10:34:39 am

Just in time for another Jurassic Park movie...

Reply

orang

6/13/2018 10:45:53 am

Excellent article. Jason, if you ever stop doing this blog, please continue to allow public access to your library of blog articles that you've done along with the search function. They are an encyclopedia of reality which i've used to get the real scoop on a couple of things.

Reply

AC

6/13/2018 12:19:52 pm

Tetrapod zoology is a blog hosted on the Scientific American website's blogs section, so I'm not sure if SA technically 'published' it or just hosted it.

Reply

6/13/2018 12:28:25 pm

Good question. I wasn't sure exactly who was the ultimate owner, but it appear under their brand name, so I went with it.

Reply

Bob Jase

6/13/2018 02:22:22 pm

Now Jason, if facts mattered then ...

Reply

jamesrav

6/16/2018 06:17:20 am

Interesting to read a realistic interpretation of what was actually written, and not a sensationalized version. I finally decided to google what the temperature drop was after the comet struck earth, and was shocked to learn that even in the tropics the temperatures fell to the 40's and 50's. Not exactly dinosaur weather. Must have been quite a shock to their metabolism going from average day/night temps in the 80's. But I guess a good thing it happened or we wouldn't be here.

Reply

Finn

6/18/2018 01:02:42 am

Even allowing for a slightly warmer average climate, considering many dinosaurs were insulated with feathery coats, and lived in the polar regions (where even if warm, they still faced the several months of darkness) they probably would have handled that climate change just as well as birds did. Add in that the bigger ones would benefit from mass homeothermy/gigantothermy, and big temperature changes would have had little impact - African elephants often spend time outside during snowy winters at London Zoo, with no impact.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed