|

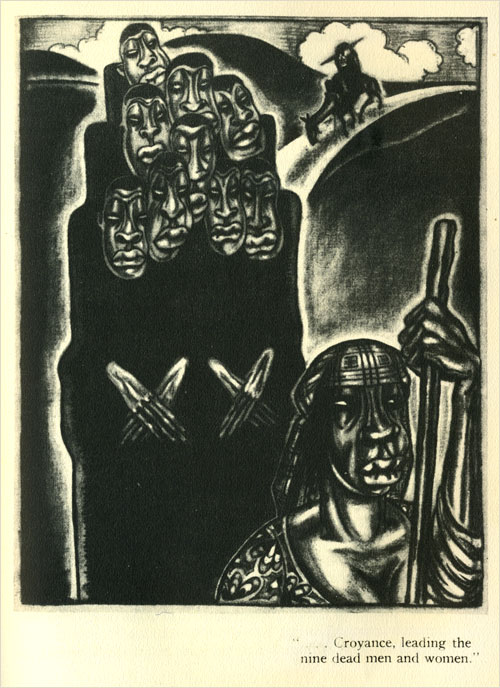

I admit to being somewhat surprised that my discussion yesterday of zombie narratives and race generated such a response, including Steve St. Clair’s claim that I was “race-baiting” in order to distract my audience…from what, I’m not sure—apparently the truth about the Sinclair world conspiracy. Since Halloween is coming up anyway, perhaps it’s worth some time to outline why I read The Walking Dead in terms of historical racial narratives. To do so, we need to go back to the beginning an understand the rise of the zombie in terms of the exotic racial Other. The word “zombie” enters the English language in the early 1800s in close association with two concepts: devil worship and African revolts against white colonial rule. As early as 1808, a French novel made reference to African slaves believing in the “zombi,” which was described as a type of devil that the slaves, being inferior to white people, worship in their ignorance. In some African faiths, the word refers to a snake deity and was later applied to the divine essence, or soul, within the individual, which sorcerers can steal. This is the foundation for the concept of the soulless zombie of modern lore, the body absent its zombie-spirit. Later in the Victorian era, European scholars refined their early Satanic definition and suggested the zombie was a type of revenant. “Are these negroes fools or asses with their Zombi?” asked an 1839 short story called “The Unknown Painter.” The word can be found in association with racial panic as far back as the 1690s when black slaves in Brazil revolted against their Portuguese masters in an attempt to establish a black-run kingdom in Brazil. The kingdom, now forgotten, lasted for forty years until the Portuguese finally defeated it. The leader of this kingdom, and the elected monarch, went by the name Zombi (apparently in honor of the god) and linked the idea of the zombie to uprisings by restless black slaves and challenges to European hegemony. The zombie was most prominent in Haiti, the first country to see a successful slave uprising that toppled a European colonial government. (Zombi merely ran a de facto state within a European colony.) But this only strengthened the connection between the mystical creature and slave uprisings—a situation that sent shudders down European spines, especially when the new dictator of northern Haiti, declaring himself a king, enslaved untold numbers of his countrymen to build himself a pleasure palace, Sans-Souci, caring not a whit how many hundreds died in the process. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Zombi was willfully misconstrued in white circles as a wicked demon that caused Black people to revolt against their white superiors. Consider Grace Elizabeth King’s The Chevalier Grace de Triton (1891) in which a black person specifically claims that the Zombi, identified as a devil worshiped by blacks, causes her to be a wicked sinner, and that if only she were white she would not be consumed in sin: That is the way! that is always the way! I tell Madame so. Zombi always gets ahead of God with me. Why did not God make me learn my catechism? If I had learned my catechism, I would have been in the room with my mistress; and I would not have heard the whistle, or I could not have come out if I had. But Zombi, he prevents my learning my catechism, he makes me put my mistress in a temper; she throws my catechism at my head, she orders me out of her room, and there I am in the kitchen, and the whistle comes; how could I know that the whistle was Master Alain’s? Zombi drives me around as if he were my master. Why does not Zombi go after my mistress? No! he is afraid of her; it’s only the poor negroes that he drives. God looks after Madame. He prevents her from sinning. Why does not God look after me? If I were white like Madame, God would look after me. How do I know what to do? God tells me to do things and Zombi tells me not; or Zombi tells me to do, and God tells me not. How can I tell what to do? Me, poor old Bambara? I can only tell afterward. Lafcaido Hearn went to the Caribbean in search of the real meaning of the word zombie in the 1880s, and I have posted the results in my Library. At that time the zombie was something of a wonder-working demon that could take human form or not as it pleased and enjoyed scaring people and playing supernatural tricks. Hearn’s sources were adamant that these creatures were not dead people, for those were confined to their graves. The zombie was something else entirely. The disconnect between the Satanic being of Victorian imagination and the trickster folk creature of actual practice only widened after this point. The fictional zombie made almost a clean break from its traditional heritage. So what does this have to do with our modern zombies? Modern zombie stories come from a confluence of several threads. The first starts with William Seabrook, an alcoholic and depressive occultist, traveler, and writer, who sought transgressive horrors, largely among non-white people (though also Aleister Crowley), and reported them for the titillation of his upper class white audience. He went to Africa and reported on black cannibals, claiming to have partaken of their food himself, which tastes, he said, “like good, fully developed veal.” He went to Arabia and reported on devil worship among the Bedouin, and he went to Haiti, which he wanted to see because of his lifelong desire to explore voodoo, which he perceived as a type of occultism. His resulting book, The Magic Island (1929), described the cultes des mortes, and reported that Haitian wizards reanimated the dead to work in the fields, and that these were zombies. Seabrook described the Haitians as “blood-maddened, sex-maddened, god-maddened,” dancing and chanting in horrible rites of ecstasy and blood. Here is the most important paragraph, which alters the Victorian zombie of Hearn into an explanation for Haitian slavery, apparently confusing symbolic explanations (i.e., “I have symbolically died because I am a slave”) for actual magic: It seemed that while the zombie came from the grave, it was neither a ghost, nor yet a person who had been raised like Lazarus from the dead. The zombie, they say, is a soulless human corpse, still dead, but taken from the grave and endowed by sorcery with a mechanical semblance of life—it is a dead body which is made to walk and act and move as if it were alive. People who have the power to do this go to a fresh grave, dig up the body before it has had time to rot, galvanize it into movement, and then make of it a servant or slave, occasionally for the commission of some crime, more often simply as a drudge around the habitation or the farm, setting it dull heavy tasks, and beating it like a dumb beast if it slackens. The book was illustrated with wickedly racist artwork by Alexander King. Here is the world’s first image of what zombies were supposed to look like: stereotypical black people marching in fearsome procession, led by a wizened voodoo practitioner and followed by Death on a mule. What few today realize is that Seabrook was writing during a period of Haitian resistance to the American occupation of the country which had begun in 1915 and would last until 1934, and the Haitians themselves, unbeknownst to Seabrook, viewed zombies as an uncanny revival of colonial-era slave-holding practices, a symbolic expression of the dehumanizing effects of the colonial (and later capitalist) exploitation of black labor, as Gyllian Phillips explored in an essay for Generation Zombie. It is inextricably tied to colonialist and imperialist fears, and emerges in the context of Haitian resistance to American involvement in the country—an occupation most modern Americans know nothing about. The American government invaded Haiti to protect white interests from a group of Germans who had intermarried with native black Haitians in order to gain economic power over the island. Other white communities, especially the Americans but also the French, refused to integrate into the black-run state and used force of arms to maintain control over the island. This is the origin point for the concept of the undead soulless and typically black corpse as a figure of horror. The success of The Magic Island led directly to White Zombie (1932), the horror movie based on Seabrook’s book. While the plot is essentially a remake of Dracula, the locus of horror shifts from the idea of the risen dead to the horror that a white woman could be taken by a half-caste voodoo master to serve among the black zombie slaves. The title pretty much gives away the central racial horror. Zombie movies down to 1968 would follow this pattern, exploring white people’s fear of the wild, unrestrained, often sexually aggressive Afro-Caribbean Other, playing on American stereotypes of black people as sexually inexhaustible savages with a lust for white women, a trope so ingrained in American culture that I trust I don’t need to illustrate it with examples. In these films, zombies were ravaging hordes of black people under the control of forces of satanic evil. I am not the only person to see this. Kyle W. Bishop did graduate research on the racist and imperialist underpinnings of zombie narratives. The second thread starts with George Romero, who did not start out to make a zombie movie. Romero originally tried to make a science fiction comedy in the vein of Plan 9 from Outer Space, with human corpses serving as the aliens’ food. It was not to be, and instead he became taken with Richard Matheson’s vampire novel I Am Legend and wanted to make a film version without actually buying the film rights. (Matheson’s novel would also serve as the basis for The Omega Man where Charlton Heston learns that vampires are people, too.) In Night of the Living Dead (1968), Romero therefore transformed Matheson’s vampires into “ghouls,” flesh-eating monsters drawn from the Arabian Nights, the Gothic novel Vathek, and early twentieth century occultism (whence came the brain-eating trope), but here betraying their vampire origins by remaining risen corpses, albeit decayed ones. (The SF angle remained only in the alien virus hinted as the source of zombie outbreak.) The Arabian ghouls were creatures that “wander about the country making their lairs in deserted buildings and springing out upon unwary travellers whose flesh they eat” (Arabian Nights, Night 31). Pointedly, these were not zombies in the traditional sense, nor did Romero call them zombies. Romero also made a black man the hero of his film, but this was fortuitous and not part of the plan. Duane Jones (“Ben”) refused to perform Romero’s original dialogue, which would have made him a stereotypically uneducated and impoverished black man. According to the actors, much of the story was improvised, including much of Jones’ role as hero. Romero, however, turned this improvisation into social commentary about race in America, with the zombies killed off by a racist sheriff’s posse, recalling the Civil Rights protests of the era. Romero later moved from racial commentary to economic commentary in his later zombie films, which tended to make the zombies symbols of capitalist tensions in society. Romero’s ghouls became conflated with the black Haitian zombies—largely after the 1980s and Wade Davis’s famous research into zombies, for a distinction is still seen in the 1970s and early 1980s literature—because both were speaking to issues surrounding what reactionary audiences perceived as uprisings against the old social order. Crazed voodoo priestesses with their armies of black undead merged with the ghouls who rose up to attack the symbols of the American social order. The Haitian zombie is largely forgotten in favor of the ghoul. Outside of Romero’s work, zombies are typically hordes of violent savages, usually in an urban environment, who attack a small group of largely white, usually upper-class survivors in order to make them part of their poor, oppressed teeming masses. Here the Other becomes the urban poor, who are disproportionately racial minorities, threatening the wealthy suburban elite. The third strand is directly related to The Walking Dead, and that is the American Western narrative of Native American attacks on white settlers. These narratives, which were wildly popular in nineteenth century pulp fiction and twentieth century cinema, generally posited a West where noble white people are spread thin across a desolate landscape where teeming hordes of violent, savage Indians could at any time erupt from the landscape to kill white people. In film, such stories began as early as The Battle of Elderbrush Gulch (1914) by the famously racist director D. W. Griffith (who eventually felt bad about his cinematic racism). John Ford’s The Searchers (1956) depicted Native people as bloody savages who attack without mercy and rape white women for sport. Ford’s Stagecoach (1939) had earlier set the template for the depiction, and both films contributed to zombie movies the trope that the endless waves of savage attackers needed to be shot. The kill shots used to put down nearly-rabid Indians are indistinguishable from the kill shots needed to put down modern zombies, for which there is no traditional folkloric need to shoot. Here’s a clip of one stereotypical Hollywood Indian attack. As you can see, in its cinematography, blocking, and action, it is identical to your standard Hollywood zombie attack. The savage other attacks the heroes, who circle the wagons and shoot them dead. They keep coming, however, and hand-to-hand combat ensues. Some heroes are wounded, but the attack is repelled—though the attackers are not vanquished. Most titillating of all were the capture and abduction narratives, popular since colonial days, which posited that white women and children could be taken by Native tribes, brainwashed or sexually dominated into joining them, and made to surrender their virtue and their claim to white civilization in favor of the savage Other. Parallel to White Zombie, two books called White Squaw from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, pretty much say it all. Captivity narratives are the subject of much scholarly work, so I am not going out on a limb to suggest this was a popular genre.

The Walking Dead purposely marries Western tropes and post-Romero zombie mythology and thus draws on both (though without taking the zombie name—that’s reserved for pop culture, as though conceding the troublesome past of the name). The series opens just like a Western, with a sheriff riding into town with his gun and on his horse. No clearer Western movie stereotype could be found. Although the show undermines Rick’s authority as Western-style sheriff and his ability to impose order on the lawless, besieged land, it nonetheless does so in the context of the Western. The stories the show tells are Western stories, even though the show is set in the Deep South of Georgia. The wagon-train-style trek across a deserted landscape (season one and part of season two) is a Western staple, as is the siege of an embattled homestead (season two), the encounter with an outlaw who promises order (season three), or the defense of the fort (season four). In using these Western tropes, how are we to read the zombies except as substitutes for the savage Native Americans of the older Western narratives? As in the capture narratives and the white-zombie stories, the ultimate fear is being taken by the savages and losing one’s identity, culture, and claim to civilization in the face of the ravages of the uncivilized Other. Compare this, though, to Syfy’s Defiance, which is also a Western in form but recognizes the racial symbolism of the narrative and incorporates Native American characters within the community to forestall this, though also at the expense of having a genuine siege narrative. You may argue that the producers of The Walking Dead, zombie fiction writers, and modern zombie-killing video games are not racist and simply view the monsters as “cannon-fodder,” a faceless enemy of no particular identity. This is a bit like the claims that Nazis are now “generic villains” who can be deployed in any narrative without the weight of their fascist and anti-Semitic baggage impacting the audience’s appreciation of the story. The zombie narrative as we have it today was jury-rigged from racist and imperialist fears of black culture and religion and grafted onto the Western Indian-attack narrative. Even if one does not mean it to, that history carries over into the story, both in form and in function. Unlike European folklore monsters—the werewolf, the vampire, etc.—which have a patina of age and deep pagan roots (the ancients wrote of both), the modern zombie story is a recent invention, of known origin, and intimately tied to America’s experience dealing with the racial Other both on the frontier and in occupied territories. Narratives that utilize the zombie can undermine it, react against it, or embrace it—but they cannot divorce themselves from the creature’s origins any more than one can remove Egypt and Egyptian resurrection beliefs from tales of vengeful Pharaohs’ mummies, even if Brendan Fraser has no idea what the Pyramid Texts actually say. Therefore, when I say that zombie tales carry this racial, colonialist, and imperialist baggage, this is not race-baiting and it is not an idle opinion based on the fact that zombies’ rotten flesh is brown but derives from centuries of history that I have researched and evaluated before opining about.

25 Comments

Brent

10/23/2013 08:28:24 am

Question:

Reply

10/23/2013 09:13:04 am

That's a great question. Undoubtedly with time symbols change meaning. We read stories of Zeus but no longer associate him viscerally with a cult complex focused on animal sacrifice, so that additional layer of meaning has faded away. That said, while young people may not recognize the reused topes in zombie stories (just as a sad number don't really have any idea what the Nazis did), they are bound to encounter them in viewing Westerns, or looking up the history zombies, etc. In that sense, the meanings matter because they will keep coming back to the surface (like zombies!) even if we don't intentionally go searching for them.

Reply

Erik G

10/23/2013 09:45:59 am

The youngsters I know who love zombies were introduced to them through video games like Resident Evil. I suspect they love zombies because it's okay to kill them as they're not human any more and dead already. Also they're ugly. Few of these youngsters read books or watch old movies. They watch The Walking Dead but I doubt the Western connection means anything to them. So yes, symbols change meaning over time. Look at what's happened to vampires over the last thirty years. And werewolves. And zombies are now becoming creatures of romance, as in the movie "Warm Bodies" this year. This pleases me immensely, because it might just mean the zombie craze is about over.

spookyparadigm

10/23/2013 11:25:43 am

Erik G, I agree that this is where much of the zombie revival began (it's way past that now, but that's where it began, and why [they were also easy for AI to control in games] IMO).

Brent

10/24/2013 01:36:07 am

There are some parts of this I agree with, but I mostly don't think the undertones are racial any more. However, I do have some thoughts on the Other and the intrinsic meanings of the monster/ tropes.

The Other J.

10/24/2013 02:31:05 am

Brent: "I might argue that zombies are especially (but clearly not exclusively) popular with younger people, who have no familiarity with the tropes' (such as hordes of "savages" attacking the wagon train) origins?"

kennethos

10/23/2013 10:07:25 am

Jason:

Reply

10/23/2013 10:15:52 am

This is an open question in literary and film criticism: Whose interpretation governs the understanding of a text? Is the author's intention the governing vision, or can a text have meaning beyond the author's intent? In Paradise Lost Milton's intention was to tell a pious story about the Fall to justify God's way to humankind, yet since its publication critics have viewed it as making Satan an epic hero. When an ignorant kid spray paints a swastika onto a wall, does it still communicate Nazism even if the kid doesn't know it as anything but a "bad" symbol?

Reply

kennethos

10/23/2013 12:11:52 pm

Your concerns are understandable, in the grand scheme of things. You may be interested in reading Kirkman's thoughts on all of this, recorded in the first couple of graphic novel trade paperbacks, which ask some very thought-provoking. (They should be available in many public library systems, and are pretty inexpensive on Amazon and WalMart, as well.) By all means, the TV series are comic are now two different beasts, with similar sets of characters (in the comics, Andrea is still alive, contra the TV series). The comic addresses themes of survival and meaning of life. The TV series seems to be addressing some other themes.

The Other J.

10/24/2013 03:07:40 am

kennethos

spookyparadigm

10/23/2013 11:17:25 am

And then there is possibly the most obvious zombie-indigenous of recent SF, the Reavers of Firefly. Yeah, Whedon SF's them up a bit in the movie, but they are for all intents and purposes, menacing Indians straight out of a traditional western tale, complete with the fear of being turned by capture (and unlike with the zombie, it is cultural/psychological). They aren't undead, but they are about as close as you're going to get to insane cannibal zombies who can still pilot starships.

Reply

Jesse M.

7/12/2018 07:16:02 pm

Even though the movie gave them more of a science fictiony explanation in-universe, on a meta level I thought the Reaver raid on the isolated frontier town made it even more obvious that Whedon was drawing on tropes about marauding Indians from old Westerns, whereas in the show we only saw an isolated Reaver who behaved more like a killer from a slasher movie.

Reply

Thane

10/23/2013 12:52:44 pm

I think it was Steven King that said "People love to be scared."

Reply

10/23/2013 01:04:31 pm

I respect your view, but I respectfully disagree. Appealing to the audience's ignorance doesn't really wash away the background of these stories, and even at their basic core (us vs. mindless savage horde) reproduce the mental world that gave rise to the earlier imperialist-colonialist version, with a small, embattled in-group defending "civilization" against the out-group, even if it is not explicitly identifying the out-group with specific out-groups from past centuries. Even when the author doesn't intend to impose meaning, meaning still exists.

Reply

Thane

10/23/2013 04:39:42 pm

"Even when the author doesn't intend to impose meaning, meaning still exists."

BigMike

10/23/2013 08:09:34 pm

"Even when the author doesn't intend to impose meaning, meaning still exists."

The Other J.

10/24/2013 04:03:44 am

"Even when the author doesn't intend to impose meaning, meaning still exists."

Shane Sullivan

10/24/2013 07:39:56 am

The Other J,

Joe

10/23/2013 03:18:17 pm

Jason, I first have to compliment you on the research and explanation into the origins of the zombie in horror and fictional literature. I understood that “zombies” had a racial origin but did not know the entire story and I appreciate the extensive work in compiling the information in your blog. But with all of the extensive work on the history of zombies I think fixating on the origins of the creation ignores the purpose of the creature. Yes I agree 100% that this is a racist origin to our current zombie creature but the origin of an idea or a fictional creation does not mean that creation maintain its original purpose. The simplistic nature of the zombie, in its single minded behavior, makes it a creature easily adaptable to symbolize any large social commentary that the author intends. As you state the original symbol might be the racial fears of the Victorian elite but that can change to communist fears of the mid sixties, to the societal fears of our present day. I do not think the current writers of zombie literature and media have a racial intent. I still agree it is important to recognize the origins of the zombie creation and if you are going to use the zombie you should understand where it came from and the implications of the creature.

Reply

Brent

10/24/2013 01:41:05 am

Just wanted to post a separate (non-dissenting) comment to say that this article was a really interesting read! It was both informative and entertaining, I enjoyed it greatly.

Reply

Gunn

10/24/2013 04:47:28 am

It looks to me like zombies can be very real. I watched a program a few years ago that showed how the Puffer Fish is the primary factor in creating real zombies. So, in other words, the modern scare is rooted in real zombies.

Reply

Only Me

10/24/2013 12:57:14 pm

And this illustrates the first and second halves of "The Serpent and the Rainbow".

Reply

Sean

11/7/2013 08:18:01 pm

Some tangential thoughts that this thread brought up. I've recently been reading quite a few 1930s American comics, since I was curious about the origins of those characters, like Superman and Batman, which became the most famous faces in the world of comics.

Reply

11/7/2013 10:36:10 pm

The literary Western as we know it today grows out of Owen Wister's Virginian, which wasn't the cowboys-and-Indians narrative we now associate with Westerns. The Western movies that used that trope (in search of action to depict on screen) derived it more from the British colonial narratives about savage Africans and (sub-continental) Indians besieging and attacking British positions.

Reply

Anonymous

10/19/2014 10:15:08 am

I just wanted to inform you that you have a grammatical error in your first sentence. I did not read the rest. *generated

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed