|

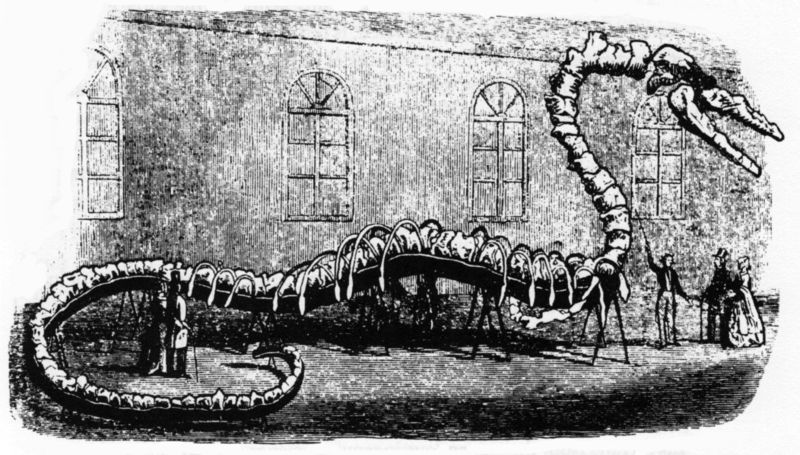

A little while back I shared a lecture that the esteemed Claude-Nicolas Le Cat gave on the subject of giants to the Academy of Science at Rouen in 1764. The full text is now on my Fragments on Giants page, but the important takeaway was that Le Cat’s lengthy list of supposed discoveries of giant human skeletons were reprinted in early editions of famous encyclopedias, such as the Encyclopedia Britannica and his lecture was recycled throughout the nineteenth century as a convenient source of “proof” of the existence of giants. Now Andy White has discovered an interesting adaptation of Le Cat’s text attributed to the scholar Benjamin Silliman, Jr., a Yale professor, chemist, and major figure in the oil industry. In 1840s, various papers claimed that Silliman gave a lecture on giants, and the text of that lecture matched the Britannica transcript of Le Cat’s lecture nearly point for point, with an odd series of typos that were as distinctive as they were clearly derived from an inferior (pirated or otherwise badly transcribed) copy of Le Cat, in which, for example, “Orestes” was given as “Grostes” or “Grestes.” Mixed in were some passages on giants from Adam Clarke’s famous commentary on the Bible and Jedidiah Morse’s Geography. To understand just what happened, let’s look at the earliest available version of the introductory text, just before Le Cat’s list of giants. This text comes from the Sunbury American and Shamokin Journal for December 14, 1844 but was widely reprinted elsewhere and is obviously summarizing an earlier report: A correspondent of the Brooklyn Advertiser, in referring to a late lecture by Professor Silliman, Jr., who mentioned the discovery of an enormous animal of the lizard tribe, measuring 80 feet in length, from which he naturally inferred, as no living specimen had been found, that all animals had greatly degenerated in size, confirms the supposition by referring to the history of giants in the olden time, of which he furnishes a list. In 1842, Benjamin Silliman, Sr., a Yale professor, chemist, and natural historian, gave a famous series of lectures on geology in New York, and these may be the lectures referred to in the Advertiser, which has not been digitized. (It was apparently very easy to confuse the two Sillimans.) So far as I can tell, only Silliman’s second lecture was reported in the New York press. In that lecture he discussed dinosaurs and other ancient lizards, according to accounts, and made reference to the Mosaic account of creation to explain the succession of animals over time. Notice very carefully that the grammar of the report’s sentence states clearly that Prof. Silliman gave a lecture on a lizard and that the correspondent provided the list of giants, obviously from Le Cat’s lecture, likely from the Britannica or a similar encyclopedia. The only ambiguity is whether Silliman or the correspondent argued for the degeneracy of species, but since the existence of dinosaurs and mammoths seemed to support that supposition, this was not a controversial claim. Later editors, though, did not distinguish between the correspondent and the professor after they chopped off reference to the Brooklyn Advertiser. In fact, the Advertiser correspondent was himself likely recycling material; he seems to have attached to an account of Silliman’s lecture a garbled version of Le Cat’s lecture that had been running in newspapers (and would run in others like the Huron Reflector) in the 1840s—without Silliman’s name—apparently from a phrenology journal (to judge by reference to phrenology and crania) as proof of giants. By 1847 Scientific American and other journals were running a misunderstood version of the story in which Silliman was now made to advocate giants: In one of his recent lectures, Professor Silliman, the younger, alluded to the discovery of the skeleton of an enormous lizard, measuring upwards of eighty feet. From this fact the Professor inferred, as no living specimen of such gigantic magnitude has been found, that the species of which it is the representative has greatly degenerated. The verity of position, he rather singularly endeavors to enforce by an allusion to the well known existence of giants in olden times. It would not be the first time Scientific American published a half-understood, garbled newspaper account in those years, as quickly rewriting and reprinting newspaper stories was its bread and butter; its concluding paragraph sarcastically agreeing that giants existed because the Bible said so is just as snarky as its (correct) dismissal of the Dorchester Pot, from a similarly confusing reprint a few years later. This version of the Silliman story was repeated over and over through the nineteenth century, sometimes with Silliman misunderstood as “Williams.” But what on earth was Silliman going on about? Here the story intersects with a fascinating case of fraud. In April 1841, Dr. Benjamin Silliman, Sr. and his son, Benjamin Silliman, Jr., attended the meeting of the Association of American Geologists where he heard Richard Harlan give a lecture on a newly discovered set of bones taken at the time to be those of a giant ocean-dwelling lizard. The bones, belonging to Basilosaurus cetoides were later shown by Sir Richard Owen and later scholars to be those of a forty million year old whale. However, in the 1840s, only the skull and spinal column were known, lending the creature the appearance of a sea-serpent, which many took it to be. Silliman certainly did, and his name became attached to a skeleton fabricated to capitalize on the new species. Silliman had been a longtime supporter of the existence of sea serpents, having endorsed the Gloucester Serpent of 1817-1819 in 1827. In 1844, a certain “Dr.” Albert C. Koch, a German scientist and mountebank who ran a museum of antiquities and oddities, traveled to Connecticut and paid a visit to Silliman, a longtime and close friend, to show him some fossils of the Basilosaurus and other species. The two had become friends in 1839, when Silliman published one of Koch’s articles on extinct megafauna in his academic journal, the American Journal of Science, and became an enthusiastic supporter of Koch’s ideas about fossils. (There is, understandably, some confusion in the sources between Silliman and his son, Benjamin Silliman, Jr., also a professor of chemistry, so others write that Silliman, Jr. was the person in question who befriended Koch.) Silliman told Koch about a woman who knew where another Basilosaurus skeleton was located, in Alabama. Using Silliman’s tip, Koch traveled to Alabama and collected the bones. Another version of the story, told by fossil hunter, Israel Slade, claimed that he and Koch met one another in Alabama and that Slade had collected the bones but lost them to Koch, who bribed the owner of the Alabama land to give them to him. Either way, Koch had two partial whale skeletons, it is true, but he fashioned it into a tourist attraction from five different skeletons, mostly whale but some of other species, and passed it off as the being of the same species but still greater than the hydrarchos Harlan had taken to Britain and studied with Richard Owen. Koch obtained his bones wherever he could find them; Basilosaurus bones were so common that Alabama residents used them in construction, or even destroyed them to clear fields for plowing. Upon the fake skeleton’s arrival at the Apollo Saloon on Broadway in New York City in July 1845 it was exhibited as Hydrarchos sillimani, after the professor, in honor of Silliman’s role in leading Koch to his newest money-maker, in some tellings, or in honor of the elder Silliman’s role in endorsing the reality of sea-serpents in 1827. This did not sit well with Prof. Jeffries Wyman, soon to be of Harvard, who railed against the skeleton as an obvious and crude fake. Wyman and Silliman knew each other well; Wyman had studied under Silliman and published in Silliman’s academic journal. Both men, along with Silliman, Jr., were members of the Association of American Geologists and were privy to the facts behind the Basilosaurus. Wyman thought much of the elder Silliman, whom he spoke of with a “feeling of deep reverence,” according to his memorial eulogy. Who better, then, to prop up the reality of the skeleton against Wyman’s attack than Wyman’s clearest equal? Koch invited his close friend Silliman to pay a visit to the skeleton, and Silliman (Sr. or Jr., depending on the source; both seemed to have viewed the bones) was enthusiastic about it to the point that, according to Koch at least, he felt compelled to spread the word to the public about the amazing creature and its history. To help promote the wonder, Silliman (apparently Sr.) allegedly wrote a letter dated September 2, 1845, which Koch published in a pamphlet for the exhibit and which was republished in many New York papers. The best I can conclude is that Silliman, Sr. really did see the bones and find them convincing—at first, at least until Prof. Wyman rained on the parade. From Silliman’s letter—be it authentic or cobbled together from reports of Silliman’s lectures on geology and/or the Basiolosaurus—we can obtain a good idea of what he or his son (for they shared common interests and common research—Jr. investigated the hydrarchos alongside his father) would have said about the bones, which he believed to be those of the Basilosaurus, in the early 1840s, before Koch had fabricated the skeleton of the hydrarchos. He began by sketching the history of the skeleton, tying it very closely to Harlan’s legitimate find and implying they were the same. The skeleton “belonging to one individual” fossilized in limestone, he said, had measured “between seventy and eighty feet long” in situ, but upon reconstruction now measured 114 feet. Therefore, we can safely assume that the lizard “80 feet in length” was in fact the Basilosaurus as Silliman understood it between 1842 and 1844. The fraudulent hydrarchos version had been found in Alabama and was one of many similar sets of bones Silliman had seen and, presumably, lectured upon: Judging from the abundance of the remains (some of which have been several years in my possession) the animals must have been very numerous and doubtless fed upon fishes and other marine creatures—the inhabitants of a region, then probably of more than tropical heat; and it appears probable also, that this animal frequented bays, estuaries and sea coasts, rather than the main ocean. As regards the nature of the animal, we shall doubtless be put in possession of Professor Owen’s more mature opinion, after he shall have reviewed the entire skeleton. I would only suggest that he may find little analogy with whales, and much more with lizards, according to Dr. Harlan’s original opinion. Note the reference to the 1827 sea-serpent claim. He then says that Dr. Koch found an arrowhead buried in an ancient strata far too old to be Native American, associated with the skeleton of a wooly mammoth, the Missourium—another fake composed from several skeletons. (Koch sold it to the British Museum for $10,000, and they disassembled it and rebuilt it the right way.) While real ancient people from the Clovis culture had in fact hunted mammoths (and many believe that despite his frauds Koch really did find a Clovis point), in Silliman’s day stone points and mammoth bones suggested antediluvian people: The bow which shot that arrow must have been bent by some “hunter of Kentucky,” long before Noah entered the ark; and the “Native American” who was on a still hunt after that Missourium, instead of being a Tarter from the north of Asia, or a descendant of the lost tribes of Israel, must have been a true Alleghanian son of the soil, of a breed somewhat older than Nimrod. And now we see how giants enter the story. Giant lizards, giant elephants, and a people older than the Biblical giant Nimrod who hunted them: To audiences, this must have implied that Silliman was discussing Bible giants themselves. Silliman, in what sounds like a fabricated passage, went on to suggest what sounded much like a Biblical theory of degeneracy: But the fossil snake! “The great serpent of the Apollo,” this is undoubtedly the grandest osteological exhibition that has ever been submitted to public curiosity; for we believe no Saurian has as yet gone beyond seventy-five feet, and this grandfather of the sea serpents would reach at least to one hundred and thirty, it the cartilage were restored to the articulations of his vertebrae. The New York newspapers were dazzled and gave glowing coverage to both the sea-serpent, which they took to be the Leviathan of the Bible, and to Silliman’s full-throated defense of it. Unfortunately, it seems that Koch overstepped. While I do not know how much of the letter is genuine, after Wyman revealed the hoax, the enraged Silliman demanded that Koch remove his name from the ridiculous skeleton, though as was his wont he phrased it as a polite request to give the honor to the first to describe the skeleton, Richard Harlan. Koch made the best of a bad situation, and he reissued all of his publicity material under a new name--Hydrarchos Harlani, after Richard Harlan, “by the particular desire of Professor Silliman.”

Before any of this occurred, Silliman (Sr. or Jr.) would have been giving popular lectures on the real skeleton of the Basilosaurus, the one Harlan had taken to London for Richard Owen’s opinion. In so doing, Silliman would likely have framed the story in Biblical terms for his audience, as was his wont in discussing geology, so as not to offend believers. The Sillimans, despite being scientists, were also devout (if not especially literal) Christians, and the elder Silliman called the Bible a “lamp to his feet.” He rejected a literal reading of Genesis, but he felt that in general science and the Bible were in harmony (“geology… presents a demonstration of the truth of Mosaic history, which nothing else can afford,” he wrote on July 24, 1854), so it is not impossible that he or his son would have cited Bible giants in describing the antediluvian world, or cited degeneracy after the Flood, following the Mosaic text and its account of the loss of the giants (human and animal) and the shortening of lifespans. Certainly, after the hydrarchos hoax that is how newspapers read the story. The New York Evangelist, for example, asked how many “giants of old” battled the monster in pre-Flood days. “Who knows but Noah had seen him from the window! Who knows but he may have visited Ararat! Who knows how many dead and wicked giants of old he had swallowed and fed upon!” In that context, Silliman’s lecture on the Basilosaurus became conflated with the question of Leviathan and Behemoth and the Nephilm and in the bastardized form from the Brooklyn Advertiser misunderstood by later editors became “proof” of Bible giants rather than a natural history lecture on prehistoric lizards. Oddly enough, there is a strange footnote to the hoax: The editor of The Mechanics’ Magazine, writing on August 19, 1848, obviously took the story for some species of lunacy. He noted that the professor’s name was “Silly-Man” and suggested that if the professor could provide proof of the existence of a single giant, he would in turn send him a copy of the fictitious “Chronicles of the Lost Atlantis,” which describes and even larger giant. The “silly man / Silliman” pun became a popular rejoinder to Koch’s exhibit, even after the name change, much to the chagrin of the Sillimans. The hydrarchos hoax skeleton didn’t fare so well either. Koch took it with him to Europe, where it found a permanent home in Dresden and in time was destroyed in the Allied bombings of World War II. Koch had also made a smaller copy of hydrarchos, but the universe killed that monstrosity with fire, too: It perished in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. But Benjamin Silliman, Sr. seemed to have forgiven Koch. Ten years later he penned a letter endorsing Koch’s smaller hydroarchos and wishing him “best wishes for your success.” Unless, of course, that letter was a fraud, too…

6 Comments

Andy White

5/20/2015 05:02:13 am

Great work! I'm still chasing down some other angles to the "origins" part of the story, and working on what happens after the "Giants of Olden Times" article becomes entrenched in the media.

Reply

David Bradbury

5/20/2015 08:29:25 am

The figure of $10,000 for sale of the Missourium skeleton-and-a-half seemed a bit high to me, so I looked it up. And soon, I wished I hadn't.

Reply

5/20/2015 08:48:02 am

Interesting. I was going by a book on geology from the 1920s, but I can imagine that the author at the time didn't bother to check the facts since it wasn't the main subject of the book.

Reply

David Bradbury

5/20/2015 08:19:56 pm

I see that the $10,000 claim appears as a direct quote via Israel Slade in "James Hall of Albany, geologist and palaeontologist, 1811-1898" by John M. Clarke (1921)- page 88. 5/20/2015 11:23:46 pm

The mention of Israel Slade in my piece probably tells you all you need to know about that.

David Bradbury

5/21/2015 01:46:32 am

Quite! Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed