|

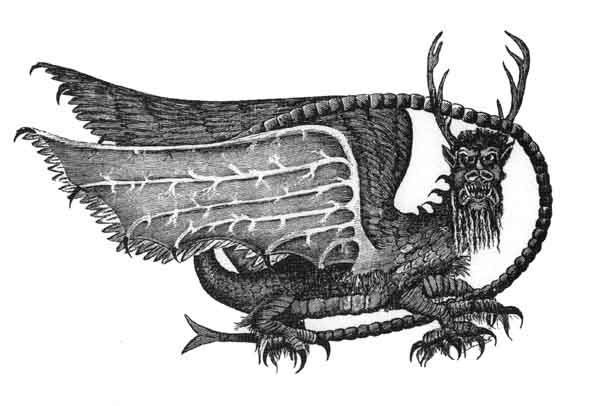

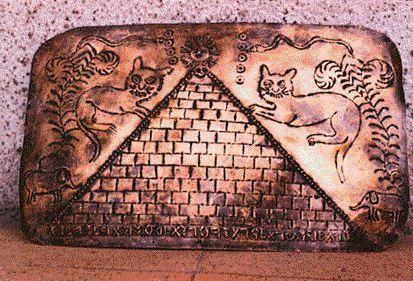

For the next few weeks, I’ll be reviewing chapters from Frank Joseph’s new alternative history anthology, Lost Worlds of Ancient America (New Page Books, 2012). This is my review of Chapters 25 through 30. (I apologize if this post loads slowly. There are a lot of pictures.) I’m starting to get fed up with Ancient American writers’ penchant for fake evidence. In Chapter 25, a Japanese scientist reports on the “connection” between Japanese dragon iconography and the so-called “piasu of Alton, Illinois,” which Nobuhiru Yoshida admits he had never heard of before an alternative historian sent him a drawing of the supposedly ancient rock art image of a dragon. Checking Frank Joseph’s other work, I find that this image is in fact a “re-creation” of an original—which, I suppose must have existed at some point since it is reported in an 1887 book, The Piasa, by Perry A. Armstrong and in earlier French travelers’ diaries. However, Armstrong’s description shows that the recreation can’t be accurate since the colors of the recreation (white, black, red, and gold) do not match those described (“but three colors were used”—red, black, and green). But—importantly—in 1887 these paisu (there were two) were already long-gone, and the only early traveler’s description, by Marquette in 1653, includes none of the imagery (such as bat-like wings) found in the recreation. This is because the drawing was probably the common Mississippian "underwater panther" image. The Alton images had been long-eroded when Marquette visited, and the last remnants were destroyed in 1856 when the rock on which they were carved was used to build the Illinois state prison at Alton. The drawing used by Joseph and Yoshida was a Victorian engraving commissioned to illustrate Armstrong’s book based on elderly residents’ memories of what the eroded outlines once looked like. IT IS NOT DRAWN FROM A REAL ARTIFACT. IT IS A VICTORIAN ARTIST’S IMAGINARY VERSION, SO YOU CAN’T BASE CLAIMS OF IDENTITY ON IT. * * * Chapter 26, by Bruce Scofield, attempts to take seriously Father Crespi’s fake gold artifacts supposedly depicting trans-oceanic contact in prehistoric Ecuador. The locals near Crespi’s residence understood that Native people were making the “artifacts” and selling them to him for profit, but to this day some people defend the largely ridiculous-looking pieces. Additionally, Scofield discusses genuine archaeological interest in the similarity between Valdivia pottery of Ecuador and the pottery of Jomon-era Japan that suggested in the 1960s trans-oceanic contact. This theory lost support when no other evidence of Japanese artifacts in America could be uncovered to demonstrate anything beyond a coincidental connection of pottery shapes. Scofield accepts the connection as real and spins an elaborate fairy tale from it that, lacking any real physical proof in the form of Old World artifacts in Ecuador, is speculation without support. I simply can’t take seriously anyone who bases claims on artifacts from the Crespi collection like this: Other Crespi artifacts are more accomplished artistically, but they are obvious stylistic pastiches, using techniques like vanishing points and perspective not invented until the Renaissance and otherwise evincing stylistic evidence of twentieth-century manufacture. * * * Chapter 27, again by Yoshida, attempts to prove Japanese contact with Easter Island and South America based this time on the fact that domes are round. Really, that’s it. A tower at Mt. Hoshigajo has a dome atop it and was built around 600 BCE. This is apparently similar to a structure seen in a Victorian lithograph of Easter Island, which, conveniently, is not reproduced. Yoshida describes it as depicting an “open enclosure” which must therefore be identical with Japanese stone enclosures. Um, no. Polynesia is littered with such “open enclosures” and they are a key element of Polynesian culture. (One, the “House of the Octopus,” has a legend attached that is a dead ringer for Cthulhu’s R’lyeh.) He then compares the dome at Hoshigajo to the “La Olla” dome in Ecuador. Yoshida claims this site, which archaeologists attribute to the Inca (c. 1400 CE), is actually must older (c. 2000 BCE), but provides no evidence why this is so other than local myths, which, as I have said more than once, don’t mean anything. The Greeks used to say the Mycenaean ruins were built by Cyclopes near the dawn of time, but that didn’t make it true. Oh, and if you try to look up “La Olla,” don’t bother. That’s not its name. Try “Olla del Panecillo,” which will inform you that the site is in fact neither ancient nor Inca. It was, apparently, built in the colonial period (though I have not seen the report of this myself). At any rate, unlike the Japanese building, the Olla was a partially-underground cistern for collecting water. Not the same thing as a mountaintop shrine. * * * Chapter 28 comes from the late Beverly H. Moseley, Jr., who was best known for creating imaginative reconstructions of ancient artifacts from a diffusionist perspective. This “article”, however, does nothing but report the discovery of a Chachapoya city in Peru. The only sop toward diffusionism is a bizarre claim that the Chachapoya were “white-skinned ‘giants.’” The claim comes from Cieza de Leon, a Spanish chronicler who described them as “the whitest people” in the Indies. This was not meant as a racial claim, since other Spanish chroniclers described all Peruvians as “white.” They just meant that their complexion was less ruddy than some other peoples, which modern analysis attributes to the founder effect, there being no genetic connection to Caucasians in their preserved mummies. * * * Chapter 29 is another entry from Wayne May, this time about stone “cairns,” or burial rocks, in Pennsylvania. (The word "cairn" is thrown in to offer a spurious hint of Celtic practice.) There is nothing too interesting here, merely a mention that the Cherokee and/or the Delaware of the region buried warriors beneath granite boulders. I’m not sure what this was meant to prove since such burials are well-documented among the Cherokee into the historic period. Typically, a warrior buried away from home was interred and rocks piled upon the tomb. Visitors would add rocks, causing the piles to grow impressively. * * * We finish Section II with Chapter 30, another entry from Frank Joseph, this time about stone walls in Texas and Iowa. The so-called “rock wall” of Rockwall, Texas (which took its name in 1851 from the “wall”) has long been mistaken for a manmade structure, but geologists have known since 1909 that it is really “a series of disconnected sandstone dikes” (i.e. a rock seams cutting across strata) that erroneously “suggest the idea that they were fragments of a ruined wall,” as Science reported in 1909. Completely natural, this “wall” falls under the alternative history category of “looks like, therefore is.” Joseph then describes similar features in Iowa, which in all likelihood have the same explanation.

3 Comments

Matt Costa

4/22/2013 09:24:05 am

I think to discount father Crespi's collection, even if certain artifacts portray vanishing points. BUT the possibility of a south american culture to discover artistic techniques is very well possible. I dont see where you got your information about the pieces being sold to father Crespi, as they were given to him by the indians for his help from my research. Either way though, further research and analysis is required. Father Crespi was a respected person in that region of Ecuador so i dont see him fabricating stories or any of that. Also, some of the pieces are now displayed in museums labeled wrongly; this is currently what I'm working on to see if there has been illegal sale to a US institution of stolen good.

Reply

Defiant

2/3/2014 07:33:00 am

LOVE the color Alton reproduction! Who wouldn't love a dragon with wings made of bacon!?

Reply

Aaron

12/24/2015 04:19:33 am

I do not normally leave comments but your statments of the Crespi collection frustrates me. You have obviously created an opinion on the collection based on little to no research on the subject. Many of the artifacts from the collection have proto hebrew writing, accurate egyptian heirogylphs, and assyrian texts. How on earth can you explain to me how rural farmers and villagers made these artifacts using languages they have no exposure too?The internet was not around back then nor were adequate libraries. So where did they get the information necessary to create these fake artifacts? Not to mention the gold artifacts are made with real gold. What would be their motivation for spending money on gold to make fake artifacts and then give them to Crespi? Crepi did pay for some of the gifts but not even enough to pay for the cost of the gold that they are made with. I encourage you to dive into this story a little deeper. I am a fairly skeptical person but this collection might be authentic!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed