|

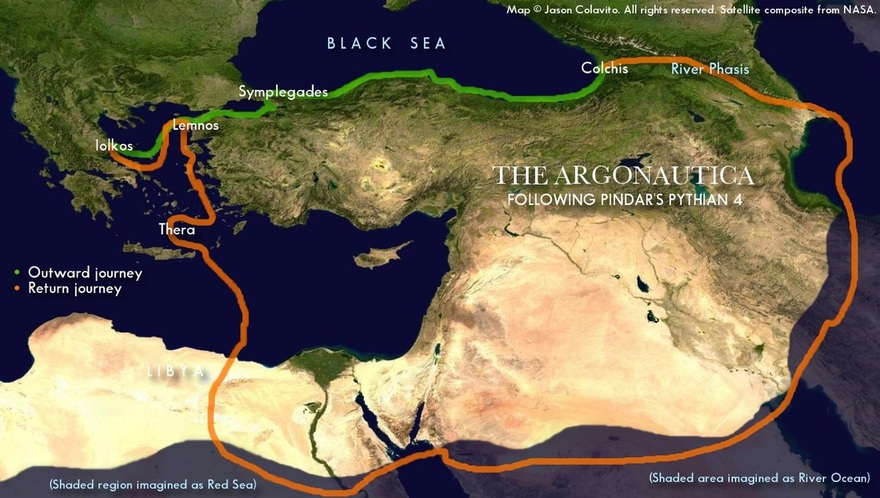

While we here in the United States get Ancient Aliens on our History-branded networks, on Australian television, their History channel is showing a six-part series by photojournalist David Adams in which the 40-year-old Aussie best known in America for his 1999 Journeys to the Ends of the Earth series explores Alexander’s Lost World. Adams is traveling in the footsteps of Alexander the Great to explore central Asia and the cities the Macedonian conqueror founded there. His thesis is that Alexander destroyed the remnants of the Oxus civilization, the Bronze Age culture of what was known to the Greeks as Bactria and to us as the region encompassing Afghanistan. While the show passes under the name of Alexander, it is apparently really about Adams’s love affair with the prehistory of Afghanistan. I haven’t seen Alexander’s Lost World in its entirety since, obviously, I don’t live in Australia, but I took the time to check out episode S01E01 “Explorations on an Ancient Sea” and S01E05 “The Land of the Golden Fleece” because it places Alexander in the context of my particular area of interest, the myth of Jason. My comments below relate to both episodes. Man, I wish I had known about this series before I finished my book on the subject, Jason and the Argonauts through the Ages. It would have made a fitting capstone to my chapter on incredibly stupid explanations for the Argonaut myth. (Disclosure: My book differs in its conclusions on the origins of the Jason myth, so I am in disagreement with Adams on almost every level.) Would you believe that Jason and the Argonauts sailed in 6000 BCE and traveled to Afghanistan to pan for gold? No? Well, Adams selectively chooses parts of the myth to make you think that his favorite country—Afghanistan—and his favorite ancient culture—the Oxus—were the center of the universe for the ancient Greeks. David Adams is apparently the Scott Wolter of Greek mythology, constructing castles of speculation on a quicksand foundation. Adams uses a replica of Jason’s boat to sail around the harbor of Volos, near ancient Iolcus, and he tells us that the most ancient Greek fragments of the myth prove that Jason traveled to Afghanistan. He says this has “everything” to do with Alexander’s trip to Afghanistan because he believes—wrongly—that the Jason myth began with an actual ancient voyage. Adams tells us that Jason was undoubtedly one of Alexander’s heroes, but this is much less certain that he makes it sound. Strabo, it is true, wrote in his Geography that Alexander’s general Parmenion built a temple to Jason at Abdera (11.14.12), but Justin, in his epitome of Trogus’ Phillipic History, writes on the other hand that Alexander’s general Parmenion destroyed the temples of Jason throughout Armenia “that no name might be more venerated in the east than that of Alexander” (42.3). But beyond this, the ancient texts have little to say about Alexander and Jason. Alexander’s greatest hero was Achilles, whose life and acts he imitated (Plutarch, Life of Alexander 5.8, 15.9, etc.; and especially Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri 7.14.4). Alexander traveled with a copy of Homer’s Iliad in a jeweled chest and slept with it beneath his pillow. The sources are silent on any particular interest in Jason. It’s possible that Adams is confusing Jason the Argonaut with the tyrant Jason of Pherae, whose tyranny in Greece and planned conquest of Asia a generation before Alexander (Isocrates, To Philip 119-20) were a model for Alexander’s own. Or, maybe Adams is just making it all up to fit his narrative about the Oxus. Adams shows us the Oxus River and the method whereby peasants used a sheep’s fleece to pan for gold, a method used throughout the region, all the way to Colchis, where Strabo first described it as being the “truth” behind the Argonaut legend in a rationalization. If you aren’t familiar with Strabo’s claim, it’s worth thinking about in detail because it isn’t what it seems. Here’s what Strabo says, speaking of Colchis: “In their country the winter torrents are said to bring down even gold, which the Barbarians collect in troughs pierced with holes, and lined with fleeces; and hence the fable of the golden fleece” (11.11.19). Gibbon accepted this explanation, and in the twentieth century it became the standard explanation for the Golden Fleece, mostly by scholars in fields other than Classics, who weren’t acquainted with euhemerism or Strabo’s biography. Strabo was a rationalizer, and he proposed many “explanations” for myth of greater or lesser probability, but the Fleece is for him particularly special. He wanted it to symbolize the wealth of Colchis (Geography 1.2.40) because Colchis was very important to him, as was its wealth. Strabo’s great-uncle was governor of Colchis (Geography 11.2.38), so providing a factual basis for the Jason myth—and one that emphasized the wealth and power of Colchis, where gold bubbled up from the rivers—reflected back on the glory of Strabo’s family. Adams shows us a muddy lump of wet sheepskin and asserts that this is the truth behind the Golden Fleece, despite the obvious fact that the muddy lump bears no resemblance to the mythic version, and that Afghanistan is nowhere near Armenia or Colchis, the lands where the Greeks explicitly placed the Fleece. Besides, in myth the Fleece travels from Greece to Colchis, so why would we look for an origin where the earliest Greeks explicitly denied it originated? Adams says that because there is no evidence of Mycenaeans in Colchis, we must assume that all of the Greek myths of Jason—while still literally true accounts of real voyages—are also false. He refuses to believe that the Golden Fleece is anything but a symbol of gold mining—making it one of only two myths about industrial labor (the other being Hephaestus as blacksmith)—and therefore says we must look for evidence of places where gold was mined. He says we should refer back to the oldest layer of myth, but here he fails again. In the oldest layers of myth the land to which Jason sailed was Aea, the dawn-land where the sun rests at night (Mimnermus, preserved in Strabo, Geography 1.2.40). This was somewhere in the farthest east. But Homer—our absolute oldest source for the Jason story—knows nothing of Afghanistan (or the Fleece, or the Black Sea, for that matter), and his scant reference to the Argonaut journey (Odyssey 12.69-72) can tell us nothing about the geography of the voyage in those days. Careful analysis of parallel passages from the Odyssey suspected since the nineteenth century of having been recycled from Jason’s early adventures suggests instead that the Argonauts’ voyage passed by the Gates of the Underworld, where the sun emerged at dawn, in the farthest Ocean—not in a landlocked area of central Asia. It was, in short, a mythical land, only later associated with Colchis, likely after 650 BCE, when the Greeks began exploring the Black Sea. Before that, it was just as fictional as the mysterious land of the dead in the furthest west and across the Ocean that Odysseus visits to commune with the dead in the Odyssey. Or maybe Adams wants to propose that the Solutreans passed on their knowledge of America, too. Hesiod, like Homer, also knows nothing of the Fleece and seems to assume in the Theogony that the purpose of Jason’s journey was to marry what he considered an immortal goddess, Medea, a sun-maiden. Mimnermus is the first to link the Fleece to the Argonaut voyage. Adams states that the Argonauts sailed from Greece “all the way to the land of the Golden Fleece,” which he want us to read as Afghanistan for reasons discussed below. Ancient sources very clearly identify this first as the mythic dawn-land of Aea and later as the Black Sea coastal kingdom of Colchis. Adams ignores this and states instead that the rise in sea levels as the end of the Ice Age opened a waterway between the Black Sea and Caspian Seas at the Sea of Azov, which he labels the River Phasis—despite the fact that the Phasis was clearly identified in ancient geographies as being the river of Colchis, much farther south on the coast of the Black Sea. Even the earliest references to the Phasis—a geographically insecure reference in Hesiod—makes no mention of the Caspian Sea—and Homer is equally ignorant of the geography of the Black Sea. Thus, he suspects that the water route went directly to Afghanistan in 6000 BCE. Here’s the problem: Adams wants us to accept Strabo’s identification of the Fleece with gold panning equipment, but he doesn’t want us to accept Strabo’s placement of the Phasis exactly where the Greeks said it was—in Colchis, the modern Rioni (Geography 1.2.39, etc.). Besides, one of the oldest mythographers, Pherecydes, said that the Golden Fleece on an island in the middle of the Phasis (fr. 100 Fowler, from the scholia to Apollonius)—and Afghanistan is certainly no island, no matter how big the Caspian once was. In other words, Adams is picking and choosing among many claims to support his preconceived idea that the Oxus is of some vital importance to Greek prehistory. Instead, Adams rejects most of the above and asks us to accept Argonaut itinerary of Pindar (Pythian 4) and Hecataeus of Miletus, written 300 years after Homer and Hesiod failed to show any knowledge of one, let alone one beyond the Black Sea—where the Argonauts leave Colchis and travel up the Phasis to the Ocean, circle around Africa (then believed to be a thin strip of land) and cross Libya to enter the Mediterranean. Of course, these authors identify the land as of the Fleece as Colchis (Pindar says so right at the beginning of the poem, so it’s hard to miss). Adams is merely picking and choosing the parts of the stories he wants to accept and rejecting the rest as wrong. But what if the whole thing is a myth, a physical journey interpolated into an older fairy tale? “I believe the myth of Jason and the Argonauts is far older than we ever believed,” he says, tying it to… well, we shall see. Adams can’t escape his textual literalism, and he fails to account for the failures of Greek geographic knowledge, which for a centuries wrongly assumed that the Phasis connected to the Caspian Sea, which they thought was a branch of the Ocean. Ocean, of course, was not the Atlantic or the Pacific but the great river that was believed to surround the continents. His lack of grounding in Greek geographical knowledge leads him to hunt up a match wherever he can.

Adams—and I cannot believe I am writing this—next asserts that stories of Jason and the Argonauts were inspired by “the first brave mariners of the Neolithic Age,” sometime between 10,500 and 6000 BCE (!), which would be quite a trick, since that would make their story the only mythic survival from so primeval a past. Not even Zeus himself can be traced back so far. “That would be a game-changer!” he shouts. It is true that there were ships and sailing in Greece back to the Mesolithic, but there is no evidence that there were any globe-spanning journeys so early in Greek history, or that if there were tales of them would have been preserved in recoverable form after the population replacement that occurred when the proto-Greek-speakers entered Greece, or the Mycenaean collapse that followed their reign. In reality, we can trace the story back in literature no further than Homer, though his references make plain it existed before then. Applying Martin Nilsson’s theory on the Mycenaean origins of Greek mythology to the Jason story can give us an earliest formation date at some time in the late Mycenaean or Sub-Mycenaean period, with the bulk of the formation occurring the during the Greek Dark Ages. There is scant evidence for Mycenaean incursions into the Black Sea (some Mycenaean-style anchors have been found on the western Black Sea coast), and none earlier. The Indo-Europeans who entered Europe and eventually became the Mycenaeans and told Jason’s story came from central Asia around 6000 BCE, it is true, but they didn’t go from there to Greece by ship but rather over land. Nor does Adams explain why we should accept the claim that the Argonauts left the Black Sea for the Ocean as true but not the part where they sailed around Africa and carried the Argo across the Sahara (Pindar, Pythian 4). You don’t get to pick and choose reasons why Pindar has a fixed itinerary but Homer and Hesiod have a vague fairy tales, or why we should accept Pindar (who rewrote the myth to persuade Arkesilas IV to recall an exile back to Cyrene) instead of any other author. Adams’s hypothesis obviously bears similarities to the claims that the same change in sea levels in the Black Sea also gave rise to the myth of Noah’s Flood, and this brings us back to Jacob Bryant’s claim that Jason’s Argo was a corruption of the pure Genesis narrative of Noah’s Ark. Buts still more clearly Adams’s claims resemble those of the Victorian solar myth theorist F. A. Paley, who in 1879 took from the alternate name of the Symplegades (the Clashing Rocks), the Cyanae (the Blue Rocks), a truly novel hypothesis. Accepting the late identification of the Cyanae with the Bosporus (earlier Pindar, for example, had placed them on the homeward voyage, where they could not be the Bosporus), he decided that the only “rocks” that were blue and moved were icebergs, so therefore the Jason myth recorded a memory of what scientists had only recently proposed to be a prehistoric Ice Age! The icebergs broke off of glaciers, floated across the Black Sea, and beached themselves on the Bosporus when the Black Sea broke open and flooded the Aegean—the reverse of the Noah’s Flood hypothesis—as Diodorus had reported: “And the Samothracians have a story that, before the floods which befell other peoples, a great one took place among them, in the course of which the outlet at the Cyanean Rocks was first rent asunder and then the Hellespont” (5.47.3). Thus, for Paley, “It may be a record, or rather a dim tradition, of a remote pre-historic period, reaching back nearly to that ‘glacial’ era, the existence of which appears to be now generally accepted as a scientific certainty.” Of course Paley didn’t know how long ago the Ice Age was, and if he did he likely would have revised his opinion. Paley’s view, however, was taken up by George Cox in his famous Aryan Mythology, and from there it shows up on occasion in later works. This was rather frustrating because Paley, despite his wrongheaded obsession with the solar theory, was among the first to recognize that there had to have been a substantial body of Jason myths before Homer. In short, Adams doesn’t know what he’s talking about and has broadcast a completely fictitious narrative about the Jason myth all the way around the world (the show airs in several countries) based on what seems to be a fantasy about the centrality of Afghanistan to world history.

7 Comments

KIF

3/24/2014 06:34:45 am

Crius Chrysomallus, offspring of Poseidon and the nymph Theophane

Reply

3/24/2014 01:54:09 pm

So tell us how you really felt about it, Jason. :)

Reply

3/24/2014 01:59:25 pm

It's a good thing I didn't watch the other four hours. I can't imagine what injuries Adams inflicted on poor Alexander!

Reply

3/25/2014 06:17:05 am

Oh, I am interested. I didn't even know it was possible to find the origins of archaic myths until discovering books like Lane Fox's "Travelling Heroes." Astounding what we can discover, or at least make decent hypotheses.

Narmitaj

3/25/2014 02:00:26 am

I did a search of your site, but can't see that you have checked out Michael Wood and his take on Jason though perhaps you have. BBC docco here, probably on PBS at some point: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZRV21N5bz-s And his written text on the same subject: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/greeks/jason_01.shtml

Reply

3/25/2014 02:13:43 am

My comments on Wood aren't online, but I do discuss his views in my book. He's wrong, too.

Reply

KIF

3/25/2014 05:13:11 am

Wonderful 1963 film version by Don Chaffey

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed