|

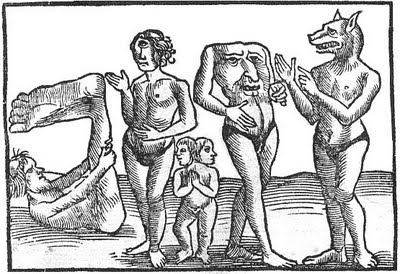

I’ve spent an inordinate amount of time tracing the alleged “mysteries” of Muslim and African “discoveries” of America, based largely on misconstrued texts from the journals of Christopher Columbus. After debunking nearly everything on the standard list of “evidence” for Muslim exploration of the pre-Columbian Caribbean, I need a little break. So today, let’s look at Columbus and Greek mythology. First, a fun passage from Columbus (as redacted by Bartolomé de Las Casas) on the events of January 9, 1493, during his first voyage: El día passado, quando el almirante yva al río del oro dixo que vido tres serenas, que salieron bien alto de la mar; pero no eran tan hermosas como las pintan, que en alguna manera tenían forma de hombre en la cara. dixo que otras vezes vido algunas en Guinea en la costa de la Manegueta. This passage has been used in the mermaid literature (and, sadly, there is an entire genre of mermaid pseudoscience) to suggest that Columbus actually saw mermaids, but even the Spanish authors who immediately followed in Columbus’s wake doubted this. Las Casas himself made note that these were almost certainly manatees. Columbus’s description echoes that of Oviedo in the Natural History of the Indies, where the writer describes (chap. 85) manatees as “of an ugly appearance.” Certainly, most later authors have understood this as referring to manatees. It’s interesting that Columbus (via Las Casas) uses the word “serenas”—from the Sirens—to represent the mermaids. Sirens, of course, were bird-women in Greek myth, while mermaids were fish-women most fully developed in medieval lore. But since the sirens were associated with the sea, they became confused with mermaids. Columbus also recorded an interesting legend of the native peoples of Cuba, about one-eyed men who lived somewhere to the southeast, in a land called Bohio, which Las Casas and later writers have suggested was meant to represent Hispaniola. From standard translations: He also understood [from the Indians] that, far away, there were men with one eye [hombres de un ojo], and others with dogs’ noses who were cannibals, and that when they captured an enemy, they beheaded him and drank his blood, and cut off his private parts. (Nov. 4, 1492) While this is hardly news—stories that the people beyond the shore were zany mutants and cannibals are nearly a human universal—what is interesting is that some Victorian writers tried to make this into proof of Greek mythology! Mary H. Hull, in her children’s book Columbus and What He Found (1892) renders these fellows into “one-eyed giants” before adding that “Homer couldn’t have invented the one-eyed man, for we see the North American Indians had the same story. How does it happen? Can anyone tell how it is that the Norsemen, the Arabians, the South Africans, the Greeks, and our Indians were always scaring themselves about the one-eyed man?” Well, the obvious is that she’s pulled together unrelated ideas. The Greek myths have the Cyclopes, and these carry over to the Arabs, who borrowed the Polyphemus incident from the Odyssey wholesale for the voyages of Sinbad. That accounts for the Arabs. The Norse didn’t fear the one-eyed man, they worshiped him—the chief god, Odin, who gave one eye for wisdom. I will confess to being ignorant of what South African group had Cyclops myths. But there is plenty of doubt whether the story Columbus reported the Taino people as relating to him is actually true. Columbus did not speak the language, nor did the Taino speak Spanish, Hebrew, Arabic, or Aramaic, the languages of Columbus’s interpreter—who at any rate wasn’t there when the old man supposedly told Columbus about Cyclopes and dog-men. Remember, Columbus thought that he was sailing to India, and he would have read up on what he should have been finding in India. Among the ancient testimonies would have been that of Ctesias whose account of India was preserved in Pliny’s Natural History (7.2) and more fully in Photius’ Library and described dog-headed men called cynocephali. Pliny: “On many of the mountains again, there is a tribe of men who have the heads of dogs, and clothe themselves with the skins of wild beasts. Instead of speaking, they bark; and, furnished with claws, they live by hunting and catching birds.” Photius’ version adds that they eat only raw meat. It’s probably worth mentioning that the same chapter of Pliny also discusses cannibalism and Cyclopes, though not in connection with India, as well as one-legged men and men with eyes in their shoulders, this time placed in India itself. Columbus owned an Italian translation of Pliny published in Venice in 1489, and he quoted from Pliny in his writings. But we need not necessarily posit Pliny as the direct origin for the dog-nosed men of the Columbus account. The story continued through the Middle Ages, become ensconced as a staple of travel writing. Marco Polo cited them as well, placing them specifically on islands near India: Angamanain is a very large Island. The people are without a king and are idolaters, and no better than wild beasts. And I assure you all the men of this Island of Angamanain have heads like dogs, and teeth and eyes likewise; in fact, in the face they are all just like big mastiff dogs! They have a quantity of spices; but they are a most cruel generation, and eat everybody that they can catch, if not of their own race.' They live on flesh and rice and milk, and have fruits different from any of ours. (Travels 3.13, trans. Henry Yule) A nearly identical account occurs in John Mandeville and Friar Odoric, though without the spices. Now, what was Columbus looking for when he “heard” that dog-headed cannibals had an island nearby? Spices! In fact, the natives “told” him that the cannibal dog men lived where the cinnamon tress grew: “The Admiral showed the Indians some specimens of cinnamon and pepper he had brought from Castile, and they knew it, and said, by signs, that there was plenty in the vicinity, pointing to the S.E.” (Nov. 4, 1492). They then told him that the same direction was the home of cannibal dog people, as quoted above. Surely this is no coincidence that the two accounts align point for point, from spices to dog faces to cannibalism. Columbus, remembering the passage from Marco Polo, has applied Polo’s geography of India to the Caribbean and imported with it the dog-faced men. (Different scholars suggest an origin in Ctesias/Pliny or naturally-occurring upturned noses and curly hair for Polo’s description.) Most modern scholars believe Columbus was applying European ideas of some type to half-understood Taino efforts at communication; several scholars have also linked this claim specifically to Polo’s passage, though so far as I know without linking in the coincidence of spices. (Someone must have noticed this, but I am unaware of who might have done so.) Later, Columbus would return with drawings of dog-headed men to show the native people in the hopes of finding these medieval myths. Other Spanish conquistadors and missionaries claimed to hear tell of the entire bestiary of John Mandeville and Pliny, from the one-footed men (said to be in the Amazon jungle), to men with faces in their stomachs (in Venezuela, allegedly). As for the dog-men, well even Cortes had orders to search them out, though he failed to find them. A memorial to the search stood in the Franciscan monastery at Tepeaca, where the friars carved four of them into their fountain. The Turkish admiral Piri Reis, on the strength of Portuguese accounts and the records of Columbus, drew a dog-headed man in South America on his famous world map.

For nearly a century, the Spanish still tried to apply Pliny’s India to the Indies, until slowly but surely the old Classical stories faded before facts.

1 Comment

Titus pullo

7/1/2013 01:08:24 pm

Columbus was a good salesman and tactical navigator. He was a horrible manager and administrator. And like all true believers he made basic mistakes as his calculation of the circumference of the earth as other colleagues of his pointed out. That said he was the first to cross that counted in terms of changing the world and the creation of the worlds greatest republic...at least it was.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed