|

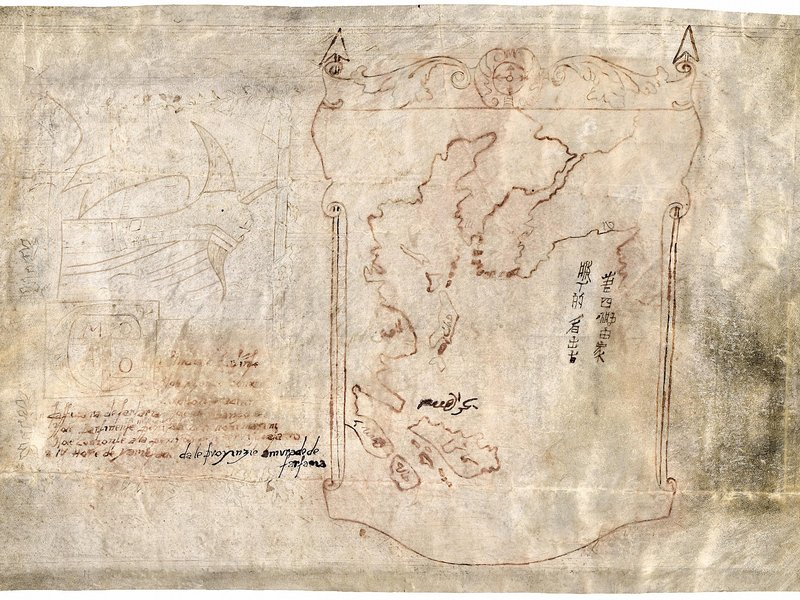

Later this week, America Unearthed will be asking whether Marco Polo discovered America. The topic seemed familiar, and I knew that the series was shooting its episodes in September of this year. It took only a few seconds to discover that the writers, who are clearly running on fumes at this point, were adapting a news report that appeared in Smithsonian magazine’s October edition and in British newspapers in late September. (So much for the Smithsonian conspiracy to suppress the truth!) According to the claim, a map drawn by Marco Polo depicting the Bering Strait was found in San Jose, California in the 1930s but not analyzed until this year. Well, sort of… Like the notorious fraudulent Zeno hoax map, the Marco Polo map is not an original, or at least doesn’t claim to be. Its advocate is Benjamin B. Olshin, who wrote a book called The Mysteries of the Marco Polo Maps about the Marco Polo map and its attendant documents for the University of Chicago Press. The book was released about six weeks ago. As it happens, the claim that the maps were not studied until this year is also false. After they appeared in the 1930s in the possession of a certain Marcian Rossi (who claimed to have inherited them from a long chain of ancestors), the Library of Congress and the FBI both investigated the maps. Olshin’s analysis is the most thorough since the maps’ emergence, but Olshin was not able to establish the authenticity of the maps. Rossi was an amateur historian (whose key interest was early exploration), an autodidact, a map collector, and a science fiction enthusiast who wrote the novel A Trip to Mars in 1920. In that book, Rossi’s characters consult with Nikola Tesla, travel to the Red Planet, and discover that Mars is ruled by ancient Romans. It sits a bit uncomfortably with me that a polyglot science fiction enthusiast with a fringe history bent and knowledge of exploration and old maps would just happen to be the owner of documents “proving” that Marco Polo beat Columbus to America. Only at the end of the book does Olshin reveal that Rossi had been peddling these documents since 1904, that he displayed them in St. Louis at the world’s fair alongside an obvious hoax—a map drawn by Pliny the Elder of the Caribbean!—and other hoax manuscripts, such as manuscript (!) texts of Pliny allegedly describing an Etruscan colony in the lesser Antilles. Oh, and Rossi later claimed all of the hoax texts except the Polo documents were destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Later, Rossi peddled other apparent hoaxes such as an Italian account of the California coast from the early 1500s. Olshin makes no mention of the improbability of any of these being real. Here I would add that the map appears at first glance to be modern. It looks like someone who drew freehand the geography of the Pacific while looking at a modern map. It doesn’t seem to have the kind of utility one might expect of a medieval map. It would be useless for sailing, for example, since it changes scale from north to south. It’s a picture of the Pacific rather than a map, and very different from the precision of Chinese cartography at the time. When comparing the Marco Polo map to other European maps of its century, it looks very different, closer akin to the disputed Vinland map, allegedly of the fifteenth century, than to medieval European maps of the early 1300s. One could, I suppose, put this down to copying material poorly, but to what purpose? Therefore, I turned to Olshin’s short book to try to find out what I could about the Marco Polo map—or, rather, maps. There are apparently twelve documents in a variety of languages (Italian, Arabic, and Chinese) featuring multiple maps, most appearing similarly to be freehand pictures rather than attempted scale representations. Olshin begins by explaining that mainstream scholars are afraid of the topic because of their “aversion to risk,” but that he bravely sought to investigate the truth. He gained access to the documents from Rossi’s great-grandson Jeffrey R. Pendergraft. Olshin makes nothing of Rossi’s special interests or previous peddling of apparent hoaxes, even though he mentions these in passing. Olshin reviews earlier opinions on the map of “Alaska,” most of which expressed doubts to its authenticity, ranging from claims of outright fraud to suggestions that a genuine medieval map of Asia had been added to much later, perhaps in the eighteenth century. Analysis of the writing on the maps showed that it did not conform to medieval or Renaissance style and could not have been written before the eighteenth century. The only question, then, was whether the maps were eighteenth century copies of a real original or a modern fraud. It’s instructive to compare the Polo documents to the Zeno hoax, with which it share many similarities. In that hoax, Nicolò Zeno the younger fabricated “recreations” of his memory of a map and letters from his ancestors, the Zeno brothers, that showed that these men had traveled the Arctic in the 1300s and therefore were worthy of greater honor than that upstart and knave Columbus. According to the hoax, the Italians heard tell of a land that could be read as America. If you were to try to create a hoax to outdo the Zeno brothers you would need four things: (a) an Italian more famous than the Zeni, (b) an Italian older than the Zeni, (c) a story of actually reaching America, and (d) actual medieval maps and letters, not just recreations. By sheer coincidence the Marco Polo papers meet all four of these criteria. Olshin, though, is more interested in trying to establish a reasonable path by which the maps might be real than to examine them for evidence of fraud. To that end, he traces the genealogy of Rossi to see if his ancestors really did interact with the Polo family, and he looks into the absence of evidence for any Polo maps (never mentioned by Polo in his book or his will, not used by any cartographer after him) for holes that would allow such maps to pass through unnoticed by history. Anyway, he gives a translation of the various documents, and the part referring to Alaska, related to Polo by a Syrian, but appearing on a different document than the map of Alaska, reads this way: He had been trading in pelts for a good thirty years, and many times [he had gone] as far as another peninsula towards the north and east called Marine Seal, which is twice as far from China. There, there are people who speak the Tartar language, and [something] hardly anyone could believe, had they not seen it themselves: the people go about dressed in sealskins, living on fish, and making their houses under the earth. A second text, this time attributed to Marco Polo himself, says that Polo sailed with ten ships to a great peninsula: “There they found caves here and there. They [i.e., the inhabitants] wear trousers and shirts of the skin of seals and deer.”

The implication, of course, is that these people are Eskimos. That this not necessarily the case Olshin accidentally notes in claiming that the story is “reflected” in the 1459 Fra Mauro map, which refers to people who “live on wild game and wear animal hides; they are men of bestial habits, and to the very north they live in caves and underground because of the cold.” One can also note that similar (though not identical) material appears in Olaus Magnus and in the Zeno hoax derived from it. It was apparently a common trope associated with northern peoples in the late medieval period, and at any rate could have derived if nothing else from an actual and known voyage to the Arctic—by the Vikings, who met the Dorset and/or Thule people (Skraelings), who conform to such descriptions, as well as the peoples of the European Arctic. Only much later does Olshin consider whether the creators of the text (if it has any genuine basis in history) might have pulled a reverse Columbus—speculating, due to ignorance of North America, that if you went east of China you’d end up in the Norse Arctic. Olshin compares the Syrian’s account to later European maps that mention men who fish and wear skins, as many Arctic peoples did on both sides of the Bering Strait. Olshin also compares the account to the famous Fusang passage of the Liang Shu from 635 CE, which claimed that the people of the far east of China use deer for cattle, and he suggests that this refers to reindeer of the Arctic. The Fusang passage is challenging on its own because it is largely mythical and encrusted with fiction. The name (as “Fusan”) actually appears on one of the supposed Marco Polo maps. Because this connection between Fusang and America occurs only in the eighteenth century, the map would almost certainly be after this date, and (I would add) probably after Leland’s popular book about the Chinese discovery of America, Fusang, in 1875—where other toponyms on the Polo map, including “Uan Scian” and “Ta Can” can be found as Wen-schin and Tahan (modern transliteration: When Shen and Da Han). While these toponyms have been known in Europe (specifically in French—as Ven-chin and Ta-han) since the 1700s, the versions used on the Polo material seem to me to be closer to nineteenth century English spellings converted back into Italian than French material, but an eighteenth century date can’t be ruled out. Olshin, though, omits Leland’s transliteration and instead stresses that the Polo versions don’t have Francophone elements and therefore must be genuine translations from Chinese. I therefore dissent from Olshin’s analysis of the toponyms as unlikely to have been back-formed from French because Leland provides everything needed to back-form the Italian without needing to return to the original Chinese or use the French. (In case you care, the “Can” in Ta-Can is a Venetian dialect use of “c” to represent “h.”) Olshin is limited in his analysis by his assumption that any presumed modern creator of the documents would have been a European working in early modern Europe rather than, say, an Italian science fiction and medieval map enthusiast living in twentieth century California. Olshin notes that the Polo material makes reference to material from Ptolemy, whose work was lost to the West until long after Polo’s day. It is therefore unlikely to be genuine, but Olshin holds out hope that the authors of the map were medieval people with special access to hidden reserves of Ptolemaic knowledge. Olshin contends that the other Polo material is unlikely to be a complete fabrication because one of the maps (of the Atlantic Ocean, nominally made right after Columbus) features the location of the toponym “Antilla,” referring to an imaginary island, whose mythology was not studied extensively until Babcock in the 1920s and Cortesão in the 1950s, and therefore unavailable to a forger of the 1700s or 1800s. Say what? I found this confusing but seems to refer to the idea that the mapmaker calculated his own system of longitude rather than borrow one wholesale from earlier writers. For example, in his 1474 letter to Columbus, Paul Toscanelli famously said that “From the island Antilla, which you call the seven cities, and of which you have some knowledge, to the most noble island of Cipango [Japan] are ten spaces, which make 2500 miles, or 225 leagues.” However, the map takes its measurements instead from the unique land of Transerica Pons appearing only on it. I’m not sure why this is a problem, and you’d think Olshin would be more wary of “Transerica Pons,” a name that looks a lot like a truncated Latin form of “Trans America Pons,” the “bridge across to America.” But since this map is admittedly one of the New World and makes mention of Columbus, it is frankly not relevant to the main question. Olshin further takes as confirmation of the documents’ authenticity a parallel found in an unusual account of Marco Polo in Ramusio’s 1558 account of geography, which suggested that Polo traveled to northeast Asia. Olshin, who doesn’t think like a hoaxer, sees this as reflecting an essential truth about the Polo texts, when it could equally well be the basis for a hoax. Besides, unrelated by Olshin, the French geographer Michel Antoine Baudrand attributed the discovery of the “southern continent” to Polo in 1681, and the Padre Dottore Vitale Terra-Rossa attributed the discovery of every land on earth to the Venetians in the 1680s. Olshin notes that Johannes Schöner mistakenly placed Polo in America when he confused cities in Mexico and China in an account of the 1530s, as did later writers like Frei Gregorio García who conflated Mexico and China and assigned both Polo and John Mandeville Mexican voyages. I would love to further analyze the written texts, supposedly by the daughters of Marco Polo, but I have already gone on too long. They contain little that could not be imagined from Victorian literature and a good library of Renaissance and medieval travelogues. Olshin concludes by evaluating the evidence for and against a hoax. He concludes—wrongly, I think—that the documents are unlikely to be a complete hoax because they are too complex and have too many details from non-Polo sources. That’s precisely why it would be good as a hoax: Simplistic hoaxes are easily exposed. He then continues his obstinate idea that if there were a hoax it had to occur in the early modern period, even though, as I have demonstrated above, someone working around 1900 would have had all the material necessary to complete it—and, in the wake of the Columbus celebrations 1892, good reason to undercut that wretched Genoese, just like the proponents of Viking, Venetian, and Sinclair discoveries of America were already doing in those same years. Olshin concludes that the documents may be modernized copies of genuine medieval material, to which details were added in later centuries. Olshin’s book is, overall, a fair and balanced account of the controversy and an interesting read. But because Olshin doesn’t think like a hoaxer and failed to consider an American rather than European provenance for the documents, he missed important avenues to consider before declaring them authentic.

32 Comments

EP

12/16/2014 07:37:55 am

I'm shocked that the University of Chicago Press would publish a book like this.

Reply

Scott Hamilton

12/16/2014 09:14:25 am

Is that a drawing of the stern of a Chinese boat to the right of the map? Has Gavin Menzies gotten his hands on these yet?

Reply

Shane Sullivan

12/16/2014 11:42:15 am

"Olshin compares the Syrian’s account to later European maps that mention men who fish and wear skins, as many Arctic peoples did on both sides of the Bering Strait."

Reply

EP

12/16/2014 12:25:33 pm

Excellent point yet again, Mr. Shane!

Reply

Shane Sullivan

12/16/2014 01:52:31 pm

Ah, the language--I knew I forgot something.

Steve StC

12/16/2014 12:29:01 pm

“It looks like someone who drew freehand the geography of the Pacific while looking at a modern map.”

Reply

12/16/2014 12:55:36 pm

I take it, Steve, that having found no way to defend America Unearthed after its recent promotion of a hoax you contented yourself with attempting to criticize my objections of Olshin's conclusions, which I may remind you, are based on a review of texts, not a scientific analysis of paper or ink. You would seriously complain that I, logically enough, say that Olshin discussed the other apparent hoaxes in passing but did nothing with the material? He mentioned the existence of the documents but failed not note they were likely hoaxes; therefore, he did nothing with the facts--he built them into no argument, sort of like the way you fail to make an argument every time you spew insults and imagine it wit.

Reply

Steve StC

12/16/2014 01:20:01 pm

Did I mention Scott or AU? Yet you mentioned him and AU more then once. Why do you have such a hard-on for Scott? 12/16/2014 01:38:41 pm

I mentioned him because you are only heard due to your repeated defenses of him, and your upcoming appearance on the show.

EP

12/16/2014 02:08:27 pm

The fact that Benjamin Olshin would participate in the "Atlantic Conference" Sinclair-fest (along with such luminaries as David Brody, author of "Cabal of The Westford Knight: Templars at the Newport Tower") tells us everything we need to know about his priorities.

Only Me

12/16/2014 05:53:09 pm

>>>Jason Colavito, renowned “Xenoarchaeologist,” can tell, at a glance, that a map is a modern forgery. Amazing. <<<

Clint Knapp

12/16/2014 04:10:26 pm

Psst. Steve. It's not 'trans-Atlantic" contact if he sailed from China to Alaska. Regardless where Polo himself originated.

Reply

Manfred

12/17/2014 04:28:42 pm

Who is Steve? You mentioned he was going to be in a future show?

Reply

EP

12/17/2014 05:12:52 pm

He's the man with magical Jesus blood and Scott Wolter's angriest fanboy. The two of them went on journey to France to look for bees.

Jerky

12/17/2014 05:27:14 pm

Oh yes, I forgot all about the bees thing.

Clint Knapp

12/17/2014 05:43:10 pm

The full story is a little hard to condense, but the gist is that Steve and his StClair DNA research project seek to identify the 'true" descendants of one Henry Sinclair who, according to a hoax, is supposed to be a Holy Bloodline descendant. So yeah, he thinks he and his family are so special that he has to sort the "true" StClaire/Sinclairs from the false. Scott Wolter considers this true and one of the lynchpins of his absurd Templar fantasies.

EP

12/17/2014 05:59:45 pm

Also, there's this from Urban Dictionary:

Jerky

12/17/2014 06:52:36 pm

Ohhh so is he that guy from the last episode of AU's season 1? where Scott went looking for the holy grail or some crap like that and told the guy with him "We are going to find your families treasure" (or something along that line), That's this Steve guy?

Jerky

12/17/2014 08:42:47 pm

I got to say, Clint Knapp, that is some good reading...

Clint Knapp

12/17/2014 08:44:57 pm

That's the one. In that particular review he comments under full name and links to his site. He shortened it to the current form, but it's the same guy.

Clint Knapp

12/17/2014 08:54:33 pm

Gunn is a different person using a pseudonym out of admiration for Steve and his own convoluted history of promoting Kennsington Rune Stone related ideas. Phil is a friend of Scott Wolter's who worked with him on Wolter's book about Lake Superior Agates.

Jerky

12/17/2014 09:14:06 pm

Oh?

EP

12/18/2014 03:01:59 am

I see we're talking about my favorite poster of all time... ;)

EP

12/16/2014 01:48:03 pm

Sup, Steve! Glad you're back! I was beginning to worry that you don't love me no more...

Reply

tm

12/16/2014 02:42:09 pm

Who won the Atlantic Conference this year?

Reply

EP

12/16/2014 02:54:18 pm

The Sinclair Atlantic Conference: Whoever Wins, We Lose

Reply

tm

12/16/2014 03:06:19 pm

Sounds like the program didn't include training in critical thinking skills. :)

Kal

12/17/2014 12:10:08 pm

Don't feed the trolls.

Reply

EP

12/17/2014 01:57:18 pm

When are they going to air Scott & Steve's UnBEElievable Adventure? (Pssst... It's the one with bees...)

Reply

Mike Morgan

12/17/2014 02:54:35 pm

SW, on his blog under "Custer"s Blood Treasure", posted the following response to a comment I can no longer find:

EP

12/17/2014 05:13:58 pm

More than you'd expect, less than you'd hope :)

Just a few observations on the "Marco Polo" map.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed