|

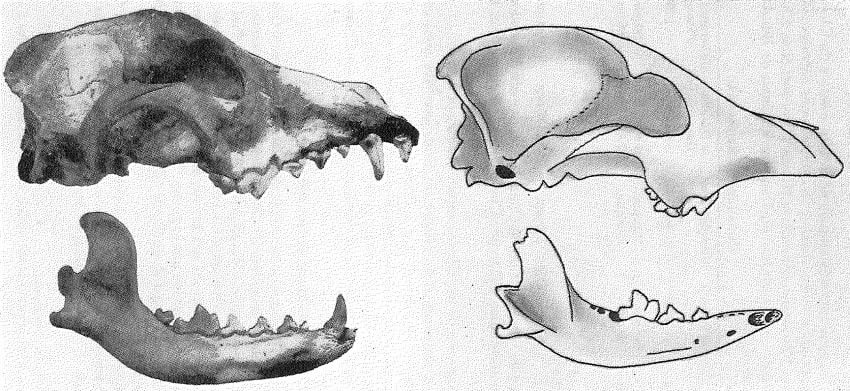

During the nineteenth century, a craze emerged for claiming the medieval Norse as the first Europeans to visit the Americas, long before Columbus. The core of the claim turned out to be true. Vikings reached eastern Canada around 1000 CE, though the Victorians had no real physical evidence of this, only a few medieval texts and some hoaxed stones. But advocates soon expanded the claim beyond the evidence and beyond logic, turning the Vikings into an early version of European imperialists, imagining them colonizing both North and South America and bequeathing European culture to the natives. The French writer Eugène Beauvois was perhaps the most extreme advocate, imagining the entire civilization of ancient Mexico the work of the Norse. In South America, the twentieth century Nazi sympathizer and Peronist collaborator Jacques de Mahieu pushed a narrative that Vikings were the first Aryan colonizers of South America, and their early efforts paved the way for the Knights Templar. This week, Ancient Origins published a piece by Geoffrey Brooks, a man who describes himself as “a pensioner” and “not an academic,” claiming that the Vikings reached South America. It ought to surprise no one that his evidence is rooted in the same nineteenth century conceptions that fueled the first run of claims attributing pre-Columbian American civilizations to the Vikings. Not a small amount is recycled, with citations, from Jacques de Mahieu, including the alleged legend of the “white king Ipir,” a supposed Viking royal reigning in the Americas. De Mahieu wrote a book about it, spinning a Viking and Nazi fantasy out of a confused legend believed by Aleixo Garcia (a.k.a. Alejo García) (d. 1525), one of dozens of misunderstood Contact-period stories where Europeans imagined “white” figures were possessors of power or wealth. In the best-known near-contemporary account mentioning the white king, Garcia went in search of “un rey blanco” and a kingdom laden with gold, but as Charles E. Nowell correctly concluded in 1946, the story was a slightly garbled account of the Inca Empire, told to a Portuguese traveling westward from Brazil by Natives who knew of Peru only through rumor and legend. The description they provided of nobles with silver crowns and heavy gold earrings and gold-inlaid belts was remarkably correct, however. The first evidence Brooks used, however, was new to me and worth discussing a bit, if only because it is so strange. Brooks says that sheepdogs from Denmark were found mummified in an Inca necropolis at Ancon, Chile in the 1880s. As we’ll see, ever part of that claim is questionable at best. Ancon is indeed a necropolis, though the Inca were the last in a line stretching back 10,000 years to use it. When Alfred Nehring found the dogs there and wrote up a German-language report about them, later published somewhere in Reiss and Steubel’s multivolume The Necropolis of Ancon in Peru that I have no interest in leafing through to find, he apparently had already come to believe that the bones were unusual. After taking measurements, he wrote in a longer 1884 paper that the bones were extremely similar to those of the European Turnspit or Dachshund. He gave the Peruvian bones their own species name, Canis ingae vertagus (i.e., the Inca greyhound). According to the scholarly literature of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, bones of dogs of a similar type could be found from Chile to Virginia, dating from the Pleistocene to the Contact period, and a major dispute surrounded the question of whether any or all of these bones belonged to the genus Canis, a different genus, or whether they represented one or more distinct species or evolution from one species over time. Various bones passed under the names Canis robustus, Pachycon robustus, Macocyon robustus, etc. In common terms, it was called the short-nosed Indian dog. Eventually, most scholars recognized the bones as Canis lupus familiaris, the familiar dog, in contradistinction to a new species bred from coyotes of wolves, or a different genus altogether. Glover M. Allen, writing in Dogs of the American Aborigines, for the Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, declared in 1920 that “There seems to be no doubt that Pachycyon robustus is after all only a breed of dog cultivated by the Indians of the southern part of North America and Peru. It is therefore no longer to be thought of as a problematical mammal of the Pleistocene.” There are, of course, two different types of dogs, both related, being discussed here. The more ancient of the two is the short-nosed Indian dog, and the more recent is the so-called Inca dog. Nehring found both at Ancon, since that necropolis featured burials from 10,000 BCE down to the Conquest. Evidence from colonial-period Spanish writers like Garcilaso de la Vega made clear that the dog was present in the Americas before the Spanish, and descriptions from the time, along with extant breeds in the twentieth century that derived from the Inca lineage, suggested that the Inca dog descended from its short-nosed ancestor, whose wolf-like appearance implied that it accompanied the first Americans into the Americas not long after the domestication of the first dog. In 1916, for example, George F. Eaton called the breed living in his day “very wolf-like,” and Allen in 1920 went into numbing detail about the dogs’ osteological similarity to native dogs found throughout the Americas. However, Brooks writes that in the 1950s, two French zoologists rejected this scientific consensus and declared that the Inca dogs could not be descended from the short-nosed Indian dogs. They argued that the bones were an exact match for a breed of sheepdog found only at Bundsö in Jutland in Denmark. Therefore, they concluded that the Danes gave some of these sheepdogs to the Vikings, who took them to Vinland, where they were traded southward after the fall of that Norse colony. Unfortunately, Brooks did not provide a reference for this article, and his description is riddled with errors that make it hard to track. He identifies the Danish dog as “Canis familiaris L.patustris Rut.” By this, he must mean that the French zoologists were referring to Canis lupus familiaris palustris, Rütim., an old name for an early breed of domesticated dog (considered its own species, Canis palustris, in the mid-1800s) that many in the twentieth century considered closely related to modern sheepdogs. However, while this ancient dog is known from examples found in Danish peat bogs (hence the name) and archaeological sites, scholars of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries did not consider it unique to Jutland but rather thought it widespread across the Neolithic world. At any rate, it wasn’t a medieval dog. While Brooks’s current article is a mess, it is a close reuse of material he posted on a discussion board in 2015, where he offered more detail. There, he confirms that I guessed the species name correctly, and he identifies the French zoologists: Madeleine Friant and H. Reichlen. That let me find their article rather easily. (Technically, Friat wrote the piece, with research by Reichlen.) Their evidence wasn’t as strong as they imagined, nor is it quite what Brooks described. The correspondences they show between the Inca dog and the Neolithic Danish one are not perfect, as they claim, even to a naked eye comparison of the two skulls, and their conclusion is still more bizarre. They concluded that the Neolithic Danish dogs remained virtually unchanged down to the Middle Ages, leaving no other trace, until the Vikings made use of their descendants and took them to Vinland, where the Natives passed them on to the Inca a few centuries later. Everything suggests that the dogs of the Vikings, about which we have no details, were the descendants of the Neolithic dogs of Scandinavia, of Bundsö, in particular. At the beginning of the 11th century, when the Indians, victorious, seized considerable booty from the Vikings, they certainly took the dogs, which they carried, in their nomadic life, to South America. And these are the dogs of the Vikings that we will find under the name of “Inca dogs” before the arrival of Christopher Columbus at the end of the 15th century. In reality, the Vikings took with them to Iceland and thus theoretically to Vinland the similar breed known as the Vallhund, which origiated around 800-900 CE.

I needn’t remark that the authors are utterly ignorant of Native life in its complexity and diversity before Columbus—much less that the Inuit of Canada were not in cahoots with the peoples of Peru—but I should remark that the entire speculation rests on the identity of the Inca dog and a Neolithic Danish dog from five thousand years earlier—with no evidence of an intermediate stage or that the Vikings’ dogs were of unchanged character from their prehistoric counterparts. The most parsimonious explanation remains that we are looking at a case where dogs, derived from the same early base stock, bred for similar tasks, achieved similar body shapes. In fact, if you remove the speculative elements from the authors’ own study, they show the same thing:

The conclusion, absent a preexisting belief in Viking global supremacy, must be that the Inca dogs share a common ancient ancestor with the Neolithic Danish dogs, probably the early domesticated dog, and breeding for similar purposes produced similar body types.

31 Comments

Kent

5/14/2020 10:12:35 am

And here I was thinking it was Scott Wolter who overturned the "Columbus first" paradigm...

Reply

Jim

5/14/2020 10:16:43 am

Canis Templari

Reply

AMHC

5/14/2020 02:12:26 pm

Got to Decenter the subject of German Idealism somehow to justify the reflexivity of political economy and economics as a Freudian or Semetic Conspiracy lest the reductionism involved be labeled ideology and Marxism....

Reply

Paul

5/14/2020 10:51:02 am

Ah, dog, the original snack food. Lewis and Clark preferred the food so there must be a Templar connection. What could be better? Dogs follow one around and when you are hungry, just bop them and throw them in the pot.

Reply

Doc Rock

5/14/2020 10:53:00 am

So the Newfie Indians kicked the Vikings asses, took their dogs,and then in typical nomadic fashion hoofed it about 8000 miles to Peru without leaving a trail of Inca dogs all along the route? Is that about right?

Reply

Kent

5/14/2020 11:41:45 am

No. What is about right is that the article asserts that Vikings brought the dogs directly to South America.

Reply

Rock Knocker

5/14/2020 11:58:38 am

Perhaps the answer is that the Newfie People hitched a ride from Canada to Peru aboard Zheng He’s Ming fleet on its voyage of discovery circumnavigating the Americas. That would explain the missing overland “trail of dogs”. Sure the timeline is off a few centuries, but when has ever gotten in the way of a good pseudo-history theory?

Reply

Doc Rock

5/14/2020 09:34:28 pm

I was referring to the translation since I thought it specifically mentioned nomadic Indians.. But with all the BS swirling around and little ole me on my third Mimosa of the morn by that time I may have missed something. Maybe they meant that the Indians invaded Scandinavia and seized the dogs there then turned around and headed to Peru. An even longer jaunt.

Reply

Kent

5/15/2020 01:27:25 am

The translation specifically refers to the Vikings' "nomadic ways" not the Indians'.

Dog Rock

5/15/2020 11:07:35 am

I'm going off of the sentence leading into the translated excerpt and the excerpt itself. Try reading it very slowly and carefully aloud and think about it. As structured, it sounds to me like they are referring to the dogs arriving in Vinland with the Vikings and then the Vikings dropping out of the process in terms of how the dogs got to Peru. You seem to be saying what Brooks interpreted from the piece not what the authors were actually claiming, if I am following this correctly. But since I am on jumbo bloody Mary number two I could be suffering from the same Blue Goose inspired confusion as yesterday.

Erik the Head

5/15/2020 12:43:37 pm

Eliminate Kent's incorrect assumption that Vikings were nomadic from one's reading of the material and there is no confusion. The discussion by the original authors regards the assertion that Native Americans seized dogs from Norse settlers in Vineland and the animals diffused to South America via population movement by Native Americans.

Kent

5/15/2020 12:46:34 pm

Sorry, Charles Nelson Mimosa.

American Disco Skraeling

5/15/2020 02:15:54 pm

There is no confusion although it may seem that way to someone who is day drinking. Kent is trying to sow discord while still coloring within the lines of the new moderation policy. Case in point his purposeful misrepresentation of the word "carried" to muddy the waters. Ignore him.

Kent

5/15/2020 02:40:37 pm

"Eliminate Kent's incorrect assumption that Vikings were nomadic from one's reading of the material..."

Darold knowles

5/15/2020 05:36:54 pm

The sentence begins with a clause describing the victorious Indians as seizing considerable booty from the Vikings to support the notion that the Indians “certainly took the dogs” which would obviously be part of said “booty.” Any other reading suggests that two contradictory ideas were jammed into the same sentence for no reason. Reading is FUNdamental.

Doc Rock

5/15/2020 09:17:42 pm

"Brooks, in his article, which I have actually read..." I commented on the translation, not Brooks. Darold can take the rest from this point.

Une Mouche Sur Le Mur

5/16/2020 06:34:03 am

Reading French and reading the entire article is fundamental. One may quibble over the precise wording of a translation. However, the final sentence of the paper on page 206 clearly asserts that the defeated Vikings retreated north and the victorious Amerindians took the dogs, as part of the booty seized from the Vikings, with them as far as South America. The authors do not specify if the same Amerindians that captured the dogs took them all the way to South America. However, this highly unrealistic scenario is implied since the authors chose to emphasize that the Amerindians were nomadic.

Fredo Eiriksdottir

5/16/2020 08:03:56 am

Native Americans physically moving from eastern Canada to Peru during the Middle Ages is impossible. A particular type of dog being traded from one group to another from eastern Canada until it arrives in Peru is highly unlikely given the time-frame involved.

Kent

5/16/2020 10:01:05 am

You've created a character who likes to drink, likes to talk about it, and makes excuses for it. Very lifelike. Good work!

Centurion Obvious

5/16/2020 01:03:16 pm

You were saying the author was saying it about the Vikings. That's not what the author said, though. So it is actually what YOU thought that the author said or what YOU wanted to believe that the author had said, and it is wrong. That's why YOU are the one in that chair. Is the difference now starting to dawn upon you?

Barna Boro

5/16/2020 07:00:47 pm

Hmmmm, Kent tries to belittle people and then cries cyberstalker when half the board turns out to take him off at the knees and Joe Scales tries to belittle people and then cries cyberstalker when half the board turns out to take him off at the knees. Mere coincidence I am sure.

Darold knowles

5/14/2020 12:18:33 pm

That was a real shaggy-dog story!

Reply

E.P. Grondine

5/14/2020 12:53:55 pm

There are a couple of excellent articles over at The Atlantic on recent Christian forgeries and the antiquities trade, and here Jason is writing brilliantly about dog skeletons. Well, one's intellectual pursuits are driving, but sometimes there are pecuniary advantages in channeling them to more lucrative topics.

Reply

Cesar

5/14/2020 05:31:31 pm

Talking about dogs, when Colonel Percy Fawcett was at the village of Santa Ana in Mato Grosso, Brazil (1913), he saw something remarkable.

Reply

Kent

5/14/2020 07:24:06 pm

Fawcett isn't a reliable source.

Reply

Cesar

5/15/2020 03:55:45 pm

https://barkpost.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/XINGU.jpg

Kent

5/15/2020 05:59:22 pm

Thanks for backing me up! One nose, two nostrils.

Farrah Fawcett

5/17/2020 10:10:14 am

How the British measured things in the 1920s is one of the great mysteries that continue to haunt mankind.

E.P. Grondine

5/14/2020 08:50:05 pm

This is for Jason's book on Islamic pyramd myths:

Reply

Lyn McConchie

5/17/2020 04:58:55 pm

I remain confused. WHY would Indians who didn't want dogs trade them to other Indians who didnt want dogs? If you don't want an item, why would you trade for it? And if you didn't want the dogs yourself, why not just eat them?

Reply

Nick Danger

5/20/2020 11:30:47 am

Mr. Colavito,

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed