|

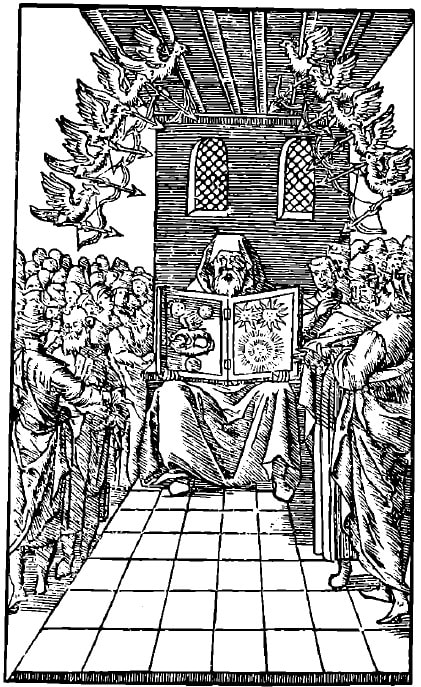

In medieval alchemy, the Emerald Tablet of Hermes took pride of place, allegedly an ancient distillation of wisdom discovered by Alexander the Great. Albertus Magnus, in a book on the secrets of chemistry written around 1200, gives the story: “Alexander the Great discovered the sepulchre of Hermes, in one of his journeys, full of all treasures, not metallic, but golden, written on a table of zatadi, which others call emerald” (trans. Thomas Thomson). This story, in turn, is a corruption or adaptation of an earlier Islamic myth, in two variants. One held that Sarah, the wife of Abraham, found the emerald tablet (written in Phoenician) held in the hands of a statue of Hermes at his tomb in Hebron, and the other than the honor fell to Balinas, who accomplished the same feat in Tyana, taking the Syriac-language tablet from the hands of Hermes’ corpse: “After my entrance into the chamber, where the talisman was set up, I came up to an old man sitting on a golden throne, who was holding an emerald table in one hand” (anonymous 1985 trans.). Another Arabic treatise, translated into Latin in the twelfth century, replaces Balinas with Galienus (an obvious misreading): “When I entered into the cave, I received from between the hands of Hermes the inscribed Table of Zaradi, on which I found these words” (trans. Steele and Singer). Zaradi, or Albertus’ corrupt zatadi, is a transliteration of a Persian word for an underground chamber, suggesting that the story originates with the Persian astrologer Abu Ma‘shar, who wrote of Hermes and his wisdom in his Thousands. The importance of the Emerald Tablet to alchemy led to a number of imitations. In the tenth century, the otherwise unknown Muhammad Ibn Umayl wrote a lengthy treatise on alchemy called the Book of the Silvery Water and the Starry Earth in which he produced a complex system of alchemy based on what he framed as ten symbols found a marble tablet held in the hands of Hermes. The text was a commentary in prose on a poem the author had written about alchemy. Ibn Umayl’s book was badly translated into medieval Latin around 1200 CE, where it became one of the oldest and most influential works of Arabian alchemy in use in the Latin West, passing under the name of Senior Zadith ben Hamuel, a corruption of its authors’ titles Sheik (Senior), “the elder” and Sadiq (Zadith) “the righteous,” and his patronymic Ibn Umayl (ben Hamuel). The frame story, delivered in the introduction, is remarkably similar to the story of Balinas at Hermes’ tomb, but set in Egypt. The detail that Ibn Umayl reports is of such quality that scholars were able to identify the location as a small temple devoted to the deified polymath Imhotep at the site of Sidar Busir, near Memphis. In the Middle Ages, statues of the wisdom demigod Imhotep were often mistaken for the wise Hermes Trismegistus because of their characteristic posture of a sitting man holding an open book. (Imhotep himself, as the Hellenized Immuthes, became identified with Asclepius, another key Hermetic figure.) Ibn Umayl’s text, though later than the proposed date for the composition of the Emerald Tablet myth, is nonetheless important because it suggests an origin point for the story of the Emerald Tablet, often assumed to originate from disparate materials in Late Antique Egypt, in a similar visit to a temple of Imhotep before passing through a Persian scholar’s recension. The text below is my translation of the Latin text, with parentheticals noting important corruptions from the original Arabic. A translation of the original Arabic appeared in Three Arabic Treatises on Alchemy, published by Muhammad Turab ‘Ali in the Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (12, no. 1) in 1933. Senior Zadith, the son of Hamuel, said: Abū al-Qāsim and I entered a birba into a kind of subterranean house, and afterward al-Hasan and I saw all of the burned-out prisons of Joseph [sic for Arabic: “the prison of Joseph, known as Sidar Busir”]. I saw on the ceiling nine painted images of eagles, having their wings extended, as if they were flying, with their feet truly extended and open. In the feet of each eagle was a large bow, like those that archers are accustomed to carry. And on the walls of the house, to the right and the left as one enters, were images of standing men as perfect and beautiful as it is possible to be, dressed in clothes of different kinds and colors, having hands extended toward the interior of the innermost chamber, toward a certain statue seated in the house, on side of the door of the innermost chamber, to the left of the one who enters, facing him. It was seated on a chair similar to the chairs of the physicians, which could be separated from the statue. In its lap and held atop its forearms and its hands, which were extended over its lap, was a tablet of marble which could be separated from the statue. It had the length of one of the forearms [sic for Arabic “one cubit”] and the width of one of the palms [sic for Arabic “one span”], and the fingers of its hands were curled over the tablet from underneath, as if it were holding the tablet. And this tablet was like an open book to those entering, as though signaling the visitor to take a look at it. And in the part of the innermost chamber where it sat, there were infinite images of diverse things and letters in the barbarous tongue [Arabic: “in the letters of the birba,” i.e., hieroglyphics]. And the tablet which it had on its lap was divided in twain. There was a line which ran through the middle. On the lower part, tilted against the statue’s chest, there was the image of two birds, one having cut wings and the other two wings, and each having its tail in the beak of the other, as if the flying one wished to fly with the other, or the other wished to retain the flying one with him. These two birds, of the same type, were depicted together in a circle, as though to make the image of the Two-in-One, and next to the head of the flying bird of the two there was a circle. And above these two birds, near to the head of the tablet, nearest the fingers of the statue, there was the image of the crescent moon. And on the other part of the tablet there was another circle, looking at [sic for Arabic “similar to”] the birds below. There were always [sic for Arabic “in total”] five images, that is to say, the two birds and [the circle] below, and the moon and the other circle.

15 Comments

Denise

8/22/2018 09:06:52 am

Now this is the book you should be publishing "Secret Hermetic Scholarship: The fascinating true history of its evolution". Or something like that.

Reply

E.P. Grondine

8/22/2018 09:54:35 am

Hi Denise -

Reply

E.P. Grondine

8/22/2018 09:57:22 am

"The Search for the Lost Knowledge of the Ancient Egyptians".

Josh Hauck

8/22/2018 12:59:04 pm

Honestly, I doubt that a real academic history of Western Esotericism would actually sell. It's all very messy, very counter-intuitive and it requires a lot of quibbling over definition and language. Maybe if Jason would write a lurid book explain how the Corpus Hermeticum predicts the coming apocalypse but it's all being covered up by UFOs and the Clinton Foundation, that might sell. But Jason won't write that (until his kid needs braces, at least.)

Shane Sullivan

8/22/2018 01:29:38 pm

There are already several books about that subject by Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke (The Western Esoteric Traditions: A Historical Introduction), Wouter Hanegraaf (Western Esotericism: A Guide for the Perplexed), Arthur Verluis (Magic and Mysticism: An Introduction to Western Esoteric Traditions), and others.

Americanegro

8/22/2018 03:39:13 pm

I've always said Jason lacks commercial drive and sense.

Bezalel

8/22/2018 09:31:45 am

Carl Jung would approve.

Reply

Carl Jung's Ghost

8/22/2018 06:43:31 pm

I was a fraud

Reply

Ken

8/22/2018 08:55:45 pm

Have ancient alchemical texts or other writings ever resulted in any useful technical clues or knowledge to modern scientists? they certainly tried mixing every known thing they could get their hands on together.

Reply

Bezalel

8/24/2018 01:40:00 pm

Ask Isaac Newton

Reply

V

8/24/2018 06:40:24 pm

I'm no expert on the subject, but I believe I remember reading several articles about how processes from alchemical texts have contributed to modern science, in a sense of "being right for all the wrong reasons."

Reply

GodricGlas

8/22/2018 10:42:23 pm

Hi, Jason.

Reply

GodricGlas

8/23/2018 01:08:14 am

Please let me know if you mean for me to hunt that down,Myself.

Reply

GodricGlas

8/23/2018 01:30:48 am

Goddamnit.

GodricGlas

8/23/2018 01:51:08 am

There’s no “commercial drive”, in Alchemy (caps due to Apple), you koad of homos.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed