|

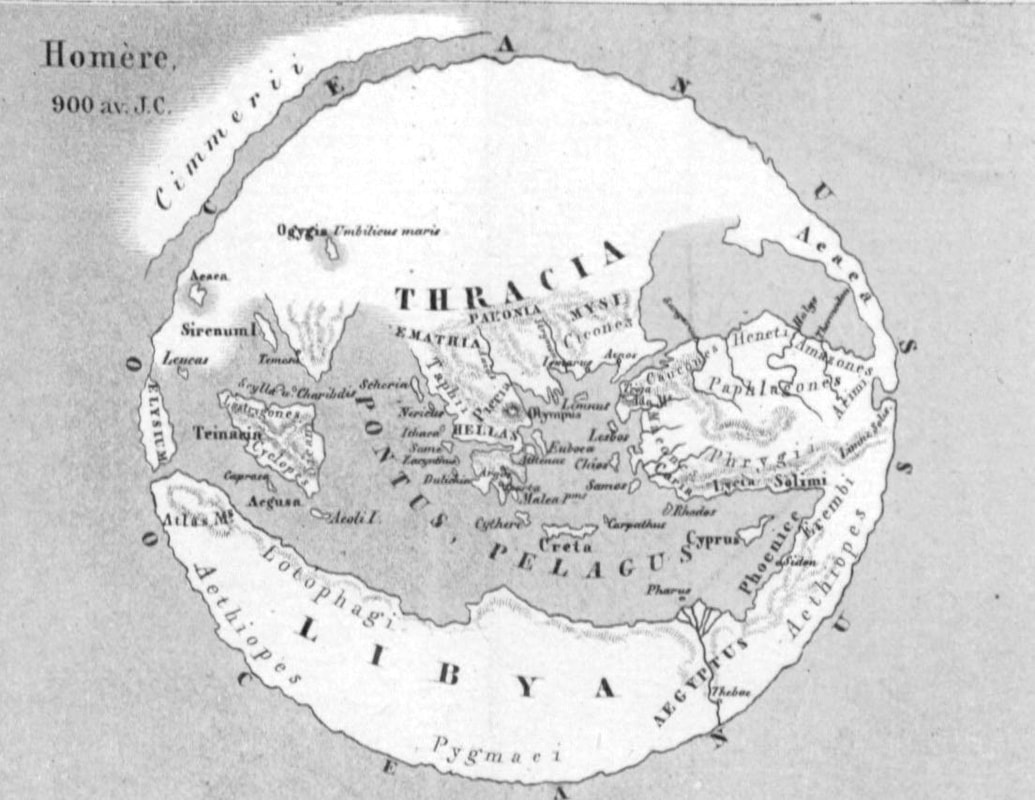

I read an interesting article about some bad research published recently in the Journal of Coastal Studies claiming that the ancient Greeks visited North America in the early decades CE, and perhaps as far back as the Bronze Age. It’s a rather textbook example of how cherry picking ancient texts outside of their established context can lead to poor results. I first learned of the claim on Friday in Hakai magazine, but it took me a few days to digest the complex chain of faulty reasoning involved. While the original journal article is locked behind a paywall, the lead researcher posted a copy to Research Gate, so we are fortunate to be able to analyze the actual arguments rather than a media summary of them. The article in question is titled, somewhat ungrammatically, “Does Astronomical and Geographical Information of Plutarch’s De Facie Describe a Trip Beyond the North Atlantic Ocean?” It was written by Greek archaeometry professor Ioannis Liritzis and a group of colleagues with even less background in the Classics, most of whom are physicists. The article was published on the Journal of Coastal Research’s website in November, ahead of a future print appearance at an unspecified date. To the best of my knowledge, the article only came to public attention this weekend when Hakai, a magazine devoted to coastal waterways, wrote about it. The foundation for the argument revolves around a single sentence in Plutarch’s De Facie, his essay on the moon. The essay, as it currently exists, is missing its opening passage. It purports to be a dialogue between some real-life people known to Plutarch during his time spent in Rome in 70s CE. The sentence comes amidst a comparison of solar and lunar eclipses and concerns an eclipse that the assembled guests were said to have witnessed: “You will if you call to mind this conjunction recently which, beginning just after noonday, made many stars shine out from my parts of the sky and tempered the air in the manner of twilight” (De facie 19.1; trans. Harold Cherniss). Now, you may not think that the sentence implies a trip to Canada, but you are not an archaeometry expert, or a physicist. They can see things that ordinary plain readings of the text cannot. Scholars have long suggested that the eclipse Plutarch alludes to refers to one of three total solar eclipses during Plutarch’s lifetime, in 71, 75, or 83 CE. Various learned arguments have been put forward for which characters in the dialogue, and the author, might have been in position to see each of these eclipses. Most of the arguments are quite strained and rely upon inferences drawn from uncertain allusions later in the text; the Loeb translator of Plutarch, Harold Cherniss, called the whole exercise “perverse,” just to give you a flavor of the quality of the discourse, and little progress has been made since the controversy received its first and fullest airing in the early 1900s. Liritzis et al. prefer 75 CE, and they take it for a given that Plutarch was describing a real meeting of his friends in the years that followed—a conclusion that is by no means certain, given the rather loose rules for the dialogue genre in Plutarch’s day. Here is where things start to break down: After this reference to the eclipse in section 19.1, Plutarch’s characters proceed to discuss the moon, the sun, and astronomical issues for several thousand words, until we come to section 26, where Sulla Sextius breaks into the discussion with an anecdote. The context here is important. In section 25, Plutarch’s brother Lamprias is discussing the possibility of life on the moon, and remarks that if Moon men were to read Homer’s cosmology, they’d think that the moon was the true Earth and the Earth is really Hades, with the heavens far above both. In other words, the argument is that what is good and normal is relative to the observer’s biases and familiarity. At this point, Sulla interrupts Lamprias. The passage is long, but important, so I will quote most of section 26 at greater length than usual. Sulla (transliterated below as “Sylla”) describes a bit of myth about the “opposite continent” of Greco-Roman lore, referring to a story told him by a stranger he met in Carthage. The text must be somewhat corrupt, for the stranger is not mentioned until halfway through, creating a bit of confusion for the reader: I had scarcely finished speaking when Sylla broke in; “Stop Lamprias, and shut the door on your oratory, lest you run my myth aground before you know it, and make confusion of my drama, which requires another stage and a different setting. Now, I am only its actor, but I will first, if you see no objection, name the poet, beginning in Homer's words: — ‘Far o’er the brine an isle Ogygian lies,’ (Od., vii, 244.) distant from Britain five days sail to the West. There are three other islands equidistant from Ogygia and from one another, in the general direction of the sun’s summer setting. The natives have a story that in one of these Cronus has been confined by Zeus, but that he, having a son for gaoler, is left sovereign lord of those islands and of the sea, which they call the Gulf of Cronus. To the great continent by which the ocean is fringed is a voyage of about five thousand stades, made in row-boats, from Ogygia, of less from the other islands, the sea being slow of passage and full of mud because of the number of streams which the great mainland discharges, forming alluvial tracts and making the sea heavy like land, whence an opinion prevailed that it is actually frozen. The coasts of the mainland are inhabited by Greeks living around a bay as large as the Maeotic, with its mouth nearly opposite that of the Caspian Sea. These Greeks speak of themselves as continental, and of those who inhabit our land as islanders, because it is washed all round by the sea. They think that in after time those who came with Hercules and were left behind by him, mingled with the subjects of Cronus, and rekindled, so to speak, the Hellenic life which was becoming extinguished and overborne by barbarian languages, laws, and ways of life, and so it again became strong and vigorous. Thus the first honours are paid to Hercules, the second to Cronus. When the star of Cronus, called by us the Shining One, by them, as he told us, the Night Watcher, has reached Taurus again after an interval of thirty years, having for a long time before made preparation for the sacrifice and the voyage, they send forth men chosen by lot in as many ships as are required, putting on board all the supplies and stuff necessary for the great rowing voyage before them, and for a long sojourn in a strange land. They put out, and naturally do not all fare alike; but those who come safely out of the perils of the sea land first on the outlying islands, which are inhabited by Greeks, and day after day, for thirty days, see the sun hidden for less than one hour. This is the night, with a darkness which is slight and of a twilight hue, and has a light over it from the West. There they spend ninety days, meeting with honourable and kindly treatment, and being addressed as holy persons, after which they pass on, now with help from the winds. There are no inhabitants except themselves, and those who have been sent before them. For those who have joined in the service of the God for thirty years are allowed to sail back home, but most prefer to settle just in the place where they are, some because they have grown used to it, some because all things are there in plenty without pain or trouble, while their life is passed in sacrifices and festivals, or given to literature or philosophy. For the natural beauty of the isle is wonderful and the mildness of the environing air. Some are actually prevented by the god when they are of a mind to sail away, manifesting himself to them as to familiars and friends not in dreams only or by signs, for many meet with shapes and voices of spirits, openly seen and heard. Cronus himself sleeps within a deep cave resting on rock which looks like gold, this sleep being devised for him by Zeus in place of chains. Birds fly in at the topmost part of the rock, and bear him ambrosia, and the whole island is pervaded by the fragrance shed from the rock as out of a well. The Spirits of whom we hear serve and care for Cronus, having been his comrades in the time when he was really king over gods and men. Many are the utterances which they give forth of their own prophetic power, but the greatest and those about the greatest issues they announce when they return as dreams of Cronus; for the things which Zeus premeditates, Cronus dreams, when sleep has stayed the Titanic motions and stirrings of the soul within him, and that which is royal and divine alone remains, pure and unalloyed. (trans. A. O. Prickard) Our current authors see this passage as inherently inseparable from the astronomy of the eclipse, and they take this thirdhand story of a distant land as a distorted account of Canada. The authors state that they simply assume this to be true based on the earlier geographical writings of Iliad D. Mariolakos, a Greek geographer who identified Ogygia with Iceland based on the idea that if Ogygia is five days’ sail from Britain, and ships sailed 5 miles per hour, it must be 480 miles away, roughly the distance to Iceland. This assumption is problematic because the direction of the prevailing winds to mythic Ogygia is unknown, and this can change the speed of a ship by a factor of five. Also, Iceland is almost 800 miles from Scotland. I will assume, however, that Mariolakos is referring to nautical miles, in which case the numbers are closer to correct. Mariolakos has adopted wholesale a claim first made in the late 1800s by the German scholar Wilhelm von Christ, the same scholar who identified Atlantis with the Sea Peoples. Mariolakos adds little that von Christ had not pioneered, though with no acknowledgement of von Christ’s priority, or of him at all. The trouble with this is that Plutarch made mention of the Ogygia legend more than once, and not consistently. While Euhemerus and Callimachus placed Ogygia in Malta, and Aeschylus thought it was Egypt, In De Defectu Oraculorum 18, Plutarch writes that the island was “lying near Britain,” and I don’t think that 800 miles would be described as “near” unless we allow so wide a latitude in accuracy as to render the point of taking Plutarch literally moot. Both claims can’t be correct unless, as is most likely, the description is literary rather than scientific, or against the prevailing winds. Plutarch even says in De Facie that the trip is against the wind (or, rather, the return voyage is with the wind), which means it would be much closer than 480 nautical miles. Earlier scholars considered these islands to be the Scilly Isles off the Cornish coast. Whatever they were, if they had a real foundation, they were close enough to have regular visits from Britain, should we accept Plutarch in De Defectu at his word. Mariolakos is a bit of a fringe believer who holds that the Minoans had colonized North America. Mariolakos dismisses academic views on Greek mythology with the claim that scholars believe mythology to be entirely imaginary (pace Martin Nilsson) and believes that Greek mythology encodes secret geological knowledge unique to North America, specifically that mythological references to the “opposite continent” on the other side of the River Ocean must be the Americas. (Johannes Kepler was the first to make this claim, many centuries ago.) All of this is based on identifying Ogygia with Iceland, and thus the other geographic features—most of which seem to be imaginary—with Baffin Island, Greenland, etc. Clearly, he’s a great source to base your whole theory on without bothering to provide evidence for why we should accept it. The authors also say that they used a 1983 article by Paul Coones, though it is not directly relevant to the issue at hand, being a discussion of natural theology. Having explored the foundations of the argument, we can now look at what Liritzis et al. did to try to prove Mariolakos (and thus, actually, von Christ) correct. It involves math. Basically, using astronomical references in the text, they compared solar eclipses with Saturn’s entry into Taurus and tried to jury-rig a coincidence. They compared this dating to records for when Saturn entered Taurus, as Plutarch wrote, to eclipses. Saturn entered Taurus in 26 CE, 56 CE, and 85 CE, staying about 2 years each time. Thus, since only one timeframe would allow the stranger to have come to Greece in time for Sulla to have met him, he must have traveled to the great continent in 26 CE and returned once Saturn left Taurus in 58 CE, taking about a year to reach his home in Greece, followed by several years’ stay at Carthage, putting him there around 65 CE, where he remained for what the authors estimate as 5 to 8 years, based on Plutarch’s description of his stay as being “too long.” This is a bit of special pleading to reach the “correct” year, close enough to 75 to match their preferred eclipse date. It also proves absolutely nothing because to declare a fictional account genuine on the basis of math is to deny that Plutarch was able to perform basic math to make the story work. At the root level, the argument is founded on the uncritical acceptance of Mariolakos’s speculative identification of Ogygia with Iceland. If we do not accept this, then the argument fails. The influence of Mariolakos is evident in an otherwise puzzling passage in which Liritzis et al. quote the section of Plutarch describing the continent’s bay as being no smaller than that of Lake Maeotis, or the Sea of Azov, and then proceed to explain that it has to refer to the Gulf of St. Lawrence because they are on the same latitude. This otherwise nonsensical conclusion came about because Mariolakos prefers to translate the section as meaning that the continent’s bay is no lower in latitude rather than smaller in size. Our authors forgot to explain that in adopting Mariolakos’s analysis wholesale. Similarly, they show off their lack of Classical knowledge when they wrongly cite the Orphic Argonautica, composed in the 400s or 500s CE, as the “oldest” account of the lands of Cronus, because they mistakenly have adopted a pre-Victorian view that the text is pre-Homeric. As the article drags on, Liritzis et al. try to squeeze more blood from the stone by taking Plutarch’s words more literally than Plutarch did. They puzzle as to why the stranger from Cronus’s continent would call Europe “the Great Island,” and they speculate that this means that the stranger came from Sicily, Crete, or some such island. But Plutarch was almost certainly being literary; the stranger, while technically an expatriate Greek, is representing the Great Continent and therefore comparing its size to Europe by calling Europe nothing more than a large island. It’s a literary inversion meant to contrast. Liritzis et al. are literal in a way that only physicists with no sense of the poetic can be. Given all of this, it is rather pointless to review the elaborate hypotheticals they propose to explain the exact routes that the Greeks would have taken to and from the Gulf of St. Lawrence, given that they are more or less trying to shoehorn Plutarch’s rather brief and loose discussion into a scientifically plausible water route, taking the better part of a year, from Crete to Norway and on to Canada. Not a trace of Greek habitation can be found along the northern reaches of that route, and I wouldn’t bet on finding any. This is a solution in search of a problem. The authors explain their analysis with the following ungrammatical gobbledygook: Based on the working hypotheses, the assumptions are elaborated against a speculative attribution. Taking on literature and historical account and applying scientific tools encourages the possible ‘‘speculation’’ to be interpreted. Obviously, the plausibility must be grounded to scientific facts; albeit tangible evidence is missing, at any rate the supportive arguments derive from an interdisciplinary approach. Archaeoastronomy is scientific, but oceanography, spherical geometry, and astronomy are also scientific and support the narration. Albeit coincidental and too good to be true, it still provides a scientific, but not mainly speculative, vehicle to unfold and decipher some ancient literature. The authors tried to reduce myth and legend to historical fact, and to do so they stretch credulity, especially when they try to argue that the Minoans weren’t just the first Mediterranean sailors to explore Norway but that their DNA bears evidence of Northern European descent! This is a reference to 2013 findings that Minoan DNA shares affinities with Western and Northern Europeans. The conclusion was that the Minoans came to Crete from mainland Europe as far back as Neolithic times, and their cousins spread out across Europe and Scandinavia. This implies nothing about continued contact in the Bronze Age. So what did Plutarch really mean by the anecdote of the distant cult of Cronus? Well, formally it is little different than other Greek tales of distant cults of various gods. Diodorus Siculus tells one about a mysterious island just south of the North Pole where a cult of Apollo serves in a strange round temple (Library 3.13). He also gives Euhemerus’ (fictional) account of the pillars of the gods on far-off Panchaea. There are obvious parallels, too, with Plato’s account of Atlantis, which would seem to be the model for the story of the island and its attendant continent. The connection to Carthage suggests, too, that the story was modeled on Pseudo-Aristotle, De mirabilibis auscultationibus 84 and Diodorus 5.19-20, in which we hear of a massive and wealthy island out in the Atlantic colonized by Phoenicians, who were also the ancestors of the Carthaginians. The point is that the story is part of an established genre of tales of magic islands across the ocean. The best that our authors have done is to demonstrate that Plutarch did some calculations to make the distances to his islands seem plausible to his readers. The opposite continent is a well-worn trope of Greek geographical speculation. It can be found as early as Homer, who wrote of the land on the far shore of the River Ocean, where Odysseus sailed to enter the realm of the dead. He similarly placed the Cimmerians across the Ocean because they were also associated with the dead. This doesn’t originate in knowledge of North America but in the old conception of the world, before Eratosthenes proved it round, which held that the three continents—Europe, Asia, and Africa—were surrounded by a massive river, Okeanos (Ocean), which in turn was ringed with lands associated with monster, the gods, and the dead. This mythic ring of land keeping the ocean from spilling down into the underworld survived the discovery that the Earth was round by becoming a continent across the ocean. Sometimes it became the Antipodes, the great southern continent that “balanced” the three in the north, as Pomponius Mela asserted. Sometimes it became a vast western continent beyond the setting sun, in which form it shows up in Plato’s Atlantis tales as the continental power base of Atlantis. It derives, ultimately, from ancient Near Eastern mythology, in which the Sun was said to have lands at the farthest edges of the Earth, through whose gates he rose and set. (Cf. Hesiod, Theogony 736-744.) It’s entirely mythological, and it requires no knowledge of the Americas to explain.

The myth at the heart of Plutarch’s tale, about the god Cronus asleep and surrounded by supernatural attendants appears to be an early version of the Sleeping King myth known from various later forms in Indo-European myth and folklore. Arthur, Charlemagne, and Frederick Barbarossa all famously shared this story. Given the location of the story, and the fact that in De defectu Plutarch says that the story was told by a man who had traveled to Britain and heard it from the Celts living there, as well as the parallels to Germanic lore and the presence of Briareus, who was associated with the Pillars of Heracles and the Celtic world beyond them, I am inclined to believe that the story as we have it is a Celtic myth, run through the interpretatio graeca by ethnocentric Greeks. This is not essential to understand what our authors argue, but it adds coloring to our understanding of the story. What it is not is evidence of Greeks in Canada, for which there is both no physical evidence and nothing in the literary account that would reflect actual knowledge of Canadian geography.

30 Comments

Irna

2/6/2018 10:29:37 am

Ioannis Liritzis has made some interesting work in archaeometry, for instance his work on surface luminescence dating of Egyptian and Greek monuments. But he also collaborated with Robert Temple (of "Sirius Mystery" fame), so I guess that the frontier between science and pseudoscience is quite blurry in his case...

Reply

Maximus

2/6/2018 10:49:09 am

This is a subject I write about too. I agree with you and a great break down from a more sensible perspective. Some of this reminds me of the myth of Apollo going to Hyperborea that Von Daniken is famous for turning into 'the aliens did it.'

Reply

Pacal

2/6/2018 10:57:16 am

I read this mess of an article. It is an outstanding example of rationalizing a mythic, poetic story. Basically the idea is that a mythic poetic account can by "rational" analysis be shown to be in fact "rational" and accurate about the real world.

Reply

Joe Scales

2/6/2018 01:03:38 pm

They're just laying the groundwork for the "Canadian colony" to become Oak Island. Then of course the infamous Roman sword will now be known as the "Greek Sword"...

Reply

Kal

2/6/2018 02:09:12 pm

Odin sleep, like in Thor as personified in the Marvel movies...Ha.

Reply

Americanegro

2/6/2018 02:17:55 pm

In general the Journal of Coastal Studies is a good journal for a layman as journals go. The idea of linking imaginary events to actual events such as the eclipse is not new, or rather not just old. It can be seen in Don DeLillo's novel about the Kennedy assassination, Libra and Gravity's Rainbow. And of course the New Testament chronologizes Jesus's birth by linking it to a census that never happened.

Reply

Machala

2/6/2018 06:25:06 pm

I always liked old Cronus. He got to rule the Titans by castrating his father, Uranus. He managed to stay in charge by eating all his kids when they were born, until his wife Rhea pulled the ole switch the rock for the baby trick, and he missed making a meal of Zeus, who grew up and stage a coup.

Reply

Doc Rock

2/6/2018 03:37:08 pm

A somewhat strange topic for this journal. Looks like it had a pretty smooth review process. I suspect that that the authors hit the jackpot in terms of the people assigned as peer reviewers. Most likely two reviewers far more familiar with oceanography than ancient Greek history and historical geography. Might have been an instance where they didn't agree with the authors, but felt that they made a decent argument relative to their tie in to oceanography, astronomy, etc.

Reply

Americanegro

2/6/2018 05:26:20 pm

The journal pretty much says "these guys say this and it sounds like a bit of a stretch." It's actually a stretch to call it a "journal". The articles I've read are more for a popular (non-academic) audience. Quite a few good reads though.

Reply

Doc Rock

2/6/2018 06:20:25 pm

It's fairly well indexed and has some decent folks as editors and on the editorial board. It has published the work of some damn good scholars. Patrick Hesp who is a pretty well known (relatively speaking) coastal geomorphologist has published several papers in it. A good friend of mine who is a well known climatologist has co-authored a paper or two in it. It doesn't have a particularly impressive impact factor ranking, though. But it's not in the basement either. Just one of many, many so-so middle-to-lower tier interdisciplinary peer reviewed journals. Strange fit for the article in question.

Americanegro

2/6/2018 07:17:13 pm

No stranger than the article on grog, torpedo juice, and whatever other alcoholic beverages sailors drink/drank.

Doc Rock

2/6/2018 07:34:46 pm

It has some stuff like that here and there, which I guess opens the door for the occasional speculative piece on ancient greeks to slip in. But most of its stuff is more along the lines of:

Reply

Americanegro

2/6/2018 08:52:31 pm

Having looked at most of the pages on their website I'd say your "most" is a bit of an oversell.

Reply

Doc Rock

2/6/2018 09:13:46 pm

Its an easy sell for anyone who has gone thru about 3 or 4 years of their past issues and checked out the titles and abstracts. Below is the link for the most current issue of the journal. Nineteen research articles and several other papers. All are along the lines of the article I referenced. None deal with grog, greeks, etc. The same is true for the 80 special issues of the journal. I have attached the link to the most recent one as well.

Reply

Americanegro

2/7/2018 12:59:37 am

My mistake. I conflated Hakai and the actual journal. Everything I said applies to Hakai and Hakai only. Sorry about that.

Maximus

2/6/2018 09:50:52 pm

The Norse could have also had contact with the Greek Culture via the waterways of eastern Europe into the Black Sea. Then later the Varangian Guard of King Sigurd created some cultural exchange between these two regions. Even Russia's Orthodox faith is due in part to their relation to the Byzantine Empire.

Reply

Americanegro

2/7/2018 03:03:02 am

In the sense that l'Anse aux Meadows was established almost 200 years before the compass began to be used in Europe that is 100% correct.

Reply

V

2/7/2018 02:38:21 pm

Not with the degree of certainty you assign it. It is a near certainty that Vinland is somewhere on the East Cost of the North American continent. It is, however, possible (not necessarily likely, but possible) that Newfoundland is Helluahland.

Reply

Patrick Shekleton

2/7/2018 02:49:40 pm

"If the Romans reached Iceland, why not also the Greek?" Whitaker, Ian. "The Problem of Pytheas' Thule." The Classical Journal 77, no. 2 (1981): 148-64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3296920.

Reply

Americanegro

2/7/2018 03:57:38 pm

Our skryers are aware of this.

Reply

Again, the eternal misunderstanding of ancient texts and how to deal with them, this time in (at least) two layers of misunderstanding:

Reply

Americanegro

2/7/2018 05:13:04 pm

"[T]he effort to make Atlantis real dies hard."

Reply

@Americanegro:

Americanegro

2/8/2018 01:21:18 pm

A bunch of dead guys were wrong so I should be wrong too? Eff that.

@Americanegro:

Americanegro

2/8/2018 02:20:57 pm

I'll see your Atlantis and raise you one Garden of Eden and one Hades. Also Mad Scientist Yakub and every planet that dead Mormons become the god of. All things that people believed at the time or believe in today.

Pacal

2/9/2018 11:02:31 pm

I am constantly amazed by the people who accept the Atlantis part of Plato's mythos. Basically they accept / that Plato's Atlantis must be a "real" place and that Plato didn't intend it to be a myth. This is interesting in that Plato in his myth devotes almost has much space to his Athens of c. 9000 years before his time and asserts that it is also real.

Reply

@Pacal:

Maximus

2/7/2018 08:33:52 pm

Rosslyn Chapel was built by an Earl of Orkney with direct Norwegian descent. The title the Jarl of Orkney is a Norwegian cultural affectation and not Scottish. The people of the Orkney Islands value their Norwegian heritage and even have a festival to celebrate this every year. So that is why Rosslyn Chapel is related to Scandinavian people. Look up the family tree of William Sinclair and the Earls of Orkney. If you think Amalfi was the only person to have developed a compass in the past then I would disagree with what you state in confidence as the earliest date a compass was used in the west. Even the description of him developing it states that he refined something that already existed. If you want to believe no one used a compass before that then that is up to you.

Reply

Americanegro

2/7/2018 10:11:03 pm

Is Rosslyn Chapel IN Orkney? Important if true.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed