|

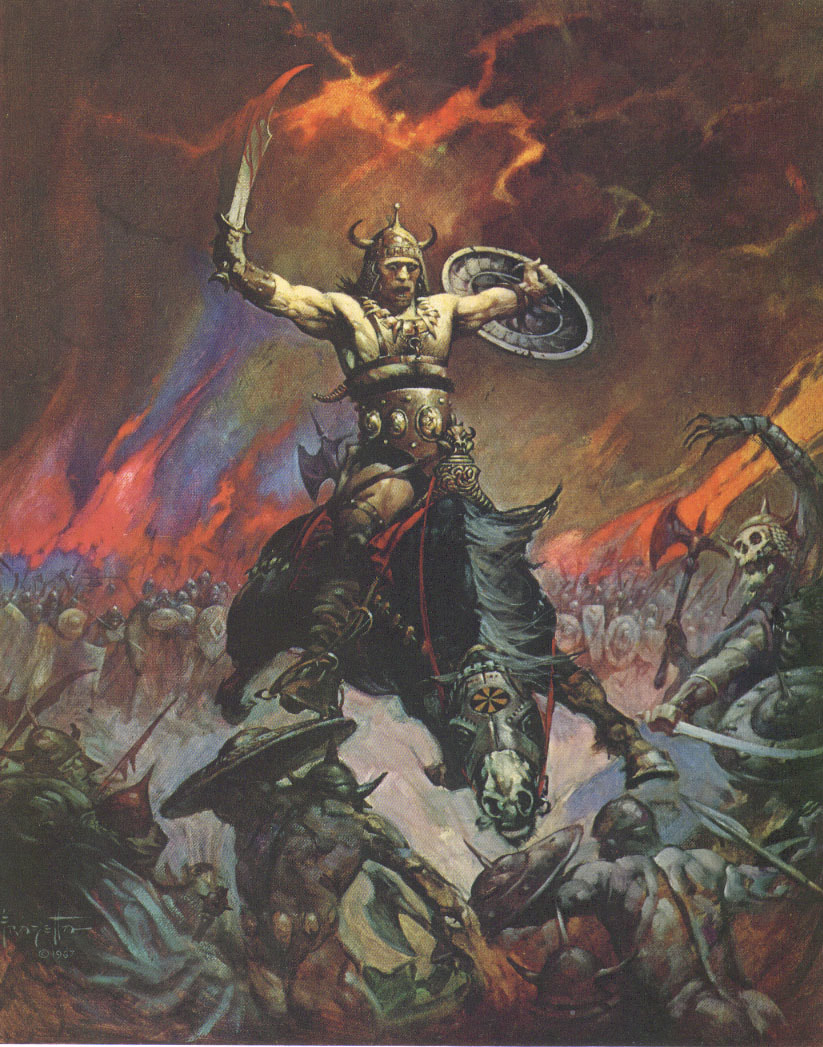

Recently, Netflix made available a multipart documentary series The Toys That Made Us, in which one episode covered the rise and fall of the Masters of the Universe toy line of the 1980s. The He-Man toys were an important part of my childhood, so I watched the episode with amusement. But the documentary also confirmed something that the creators of the toy line had danced around for decades, namely the debt that He-Man owed to Conan the Barbarian. It also led me to think a bit about the role of secondary sources in transmitting cultural ideas. There is no mistaking the family resemblance between the characters of Masters of the Universe line and heir counterparts in the fiction of Conan creator Robert E. Howard. He-Man is a musclebound barbarian in a semi-savage world fallen from great ancient heights. He battles a villain with a skull for a face and also snake men in a world of swords and sorcery. Conan is a musclebound barbarian in a semi-savage world recovering from the fall of Atlantis. Howard, in his other stories, had an Atlantean villain named Skull-Face and made villains of a race of serpent people. So close were the similarities that the owner of the Conan copyrights, Conan Properties Inc., sued for infringement, but the court ruled that (a) Conan was in the public domain for all aspects of the character developed before 1977 and (b) there was no way to separate borrowing from the public domain version of Conan from borrowing the copyrightable expressions of the idea in CPI’s version post-1977 version. For decades afterward, Mattel, the creator of He-Man, portrayed this as evidence that the company did not base He-Man on Conan. Except that they did. Just not exactly firsthand. The recent book How He-Man Mastered the Universe by Brian C. Baer and the documentary both make plain that He-Man owes a debt to Conan. The basic character design, the semi-savage sword-and-sorcery setting, and the Cthulhu Mythos-inflected backstory would not exist without Conan. Similarly, Mattel’s failed efforts to develop a Conan toy line for the 1982 Arnold Schwarzenegger movie were the impetus that sparked the creation of the Masters of the Universe line. But the details were not drawn directly from Howard. Instead, the look and feel of He-Man came from the comic book and pulp illustration art of Frank Frazetta. Frazetta had illustrated a series of covers for Conan books, and the barbarian hero depicted on them is a dead ringer for He-Man, who, as CPI once sneered, was “Conan disguised with a blond wig.” One painting, of “Conan the Conqueror,” even depicts the hero with sword raised battling a skull-faced undead warrior, and several others depict Conan in the shadow of a menacing skull. (The creator of Skeletor attributes the character to a childhood encounter with a corpse at an amusement park.) Another painting depicts Conan raising his sword as lightning strikes it, just as He-Man receives the Power of Greyskull through his sword. The early He-Man figure carried an axe and shield indistinguishable from those of Frazetta’s Conan. Other elements of the Masters toy line took inspiration from Frazetta paintings outside the Conan universe. Basically, Mattel lifted the aesthetics of He-Man from Frazetta’s interpretation of Conan and other pulp properties and then filled out the story with generic fantasy narratives drawn from a range of pulp fiction influences, half-remembered at a remove, which included Howard’s stories, B-movies, weird fiction, and other cartoons of the era. The similarities between He-Man and Conan, therefore, were only partially intentional, involving reinterpreting a visual interpretation of an unread original and adding to it elements in the Zeitgeist that had themselves passed once or twice through the Conan canon. Atop this mountain of happenstance, the exact forms were tempered by the demands of marketing and the influence of the animators of the He-Man and the Masters of the Universe cartoon series.

In seeing my long-held suspicion that He-Man and Conan were close cousins confirmed, just not exactly as I had expected, it made me think about how cultural ideas travel across time and space and about the difference between direct and indirect influence. One of the most frequent criticisms I’ve received about my analysis of the ancient astronaut theory in The Cult of Alien Gods and its sequels is that my argument that the modern ancient astronaut theory takes its shape from H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos is that Eric von Däniken didn’t know anything about Lovecraft. Indeed, when I was writing the book, Giorgio Tsoukalos, von Däniken’s protégé, argued that that my thesis was wrong because von Däniken had never read a word of Lovecraft. But the authors that von Däniken used as sources had read Lovecraft, or read authors who had. Chariots of the Gods made use of Jacques Bergier’s and Louis Pauwels’s Morning of the Magicians, which refers directly to Lovecraft. Bergier all but admitted that his interest in ancient astronauts came from trying to find a factual basis for the Cthulhu Mythos. Chariots also built on the books of Robert Charroux, who had borrowed heavily from Morning of the Magicians. In time, von Däniken would also make use of ideas from other writers like Peter Kolosimo, who explicitly cited Lovecraft as an authority on ancient astronauts. So, while it is literally true that Chariots of the Gods is not directly influenced by Lovecraft, it is nevertheless true that Lovecraftian ideas filtered down to it indirectly through its sources. Similarly, think of all the modern writers who use some version of the medieval Islamic myth that an antediluvian king built the pyramids. At least half of them have never read an original version. We saw Tsoukalos offer a bizarrely mangled version that he derived from von Däniken’s badly summarized version of a translation of the original. This kind of decades-long game of telephone animates so many bad ideas, which build on half-remembered impressions of earlier bad ideas, sometimes based on nothing more than a word or a phrase, a picture, or someone’s badly mangled description of someone else’s work.

13 Comments

Shane Sullivan

1/9/2018 11:22:47 am

" ... the barbarian hero depicted on them is a dead ringer, as CPI once sneered, for “Conan disguised with a blond wig.”"

Reply

Wim Van der Straeten

1/9/2018 01:35:31 pm

"There is no mistaking the family resemblance between the characters of Masters of the Universe line and heir counterparts in the fiction of Conan creator Robert E. Howard": "their counterparts". I guess Conan and He-Man are simply archetypes. Robert E. Howard wasn't the first author to write about muscular, mighty heroes either (think of Gilgamesh in Sumerian mythology, Hercules in Greek mythology and Simson in the Bible).

Reply

A C

1/9/2018 03:14:15 pm

Hercules is the only one of those three who goes around practically naked and that's due to Greek artistic sensibilities. Frank Frazetta was painting in a western tradition that frequently refers back to Greek art.

V

1/9/2018 03:51:28 pm

Japan has its Manly Men, too--starting with the god Susano'o, who defeated the eight-headed serpent Orochi in a tale that has its parallels to Hercules and the Hydra, and running up through the samurai tales of the Muromachi through Edo periods such as the semi-fictional stories of the many duels of Musashi. They aren't described much like Conan or He-Man. Less muscular, more emphasis on skill with the sword, usually more clothed. Spectacularly mighty heroes, though.

Americanegro

1/9/2018 05:06:30 pm

A C: Why do you grab the steering wheel and veer toward Jung? He didn't invent the word or the concept.

Jim

1/9/2018 03:44:53 pm

The depictions of Conan etc. always seemed to me to be a ripoff of the covers from Edgar Rice Burroughs novels. Amazing how scantily clad the females were on Burroughs covers for the time.

Reply

Only Me

1/9/2018 05:45:05 pm

It makes sense that He-Man would be a pastiche of Conan. In the 80s, you had a lot of different media that made use of the sword-and-sorcery genre. Dungeons & Dragons, cartoons and the several low-budget films that followed the release of Schwarzenegger's Conan the Barbarian...for a little while, the genre was popular enough to hold interest.

Reply

Bob Jase

1/10/2018 12:23:19 pm

So the creator of He-man says he based Skeletor on an encounter with the mummy of Elmer McCurdy? Except that while the amusement park was operating said mummy wasn't known to be an actual corpse, just another Halloween-style dummy, More retrocon history imo.

Reply

Totus pullo

1/10/2018 02:25:30 pm

Ok for those over 50, who temembers major matt mason? It wad during the apollo years and he tepresented the square jaw astro/test pilot hero. The interesting thing is hasbro? Introduced an alien who was a huminoid giant and friends with Matt. I think his story wad the last in a wisean old race. A meme that was popular in sci fi in those days.

Reply

AnarchyInc

1/10/2018 03:39:56 pm

odd, I watched the documentary over the holidays and do not recall a single mention of Conan within it. (did i miss it?)

Reply

Finn

1/30/2018 02:53:14 am

But hey, if nothing else, we got a cultural milestone of yelling "NYEH! HEEE-MANNNN!"

Reply

Louis-Pierre Smith Lacroix

1/31/2018 03:48:12 pm

Another inspiration for He-Man's look must be Marvel's Conan, especially as drawn by John Buscema: see the axe-wielding versions in corner box art.

Reply

Martin Stower

3/6/2018 09:59:47 am

For hair, The Mighty Thor, after a cut by Prince Valiant’s barber.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed