|

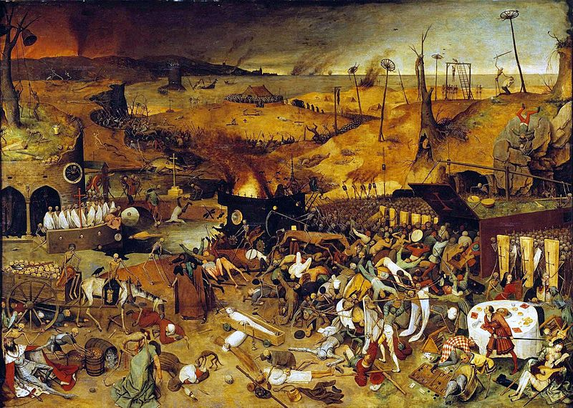

As Halloween is approaching again, the signs of the season are in the air. The leaves crunch on cold sidewalks, and the air smells of rotting vegetation. And, of course, we find zombies everywhere from the new season of AMC’s The Walking Dead to every costume shop and seasonal decoration display. But no matter how hard the media and retailers try to push zombies on me, I still don’t like them. Zombies are the only major horror monster to have been invented in the twentieth century. Everything else—from vampires to werewolves to ghosts to space aliens to psycho killers—have respectable Victorian pedigrees, or earlier. The zombie is a ramshackle lowest common denominator monster that is an accident of history. It is well known that the modern zombie derives from George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), in which the director imagined corpses rising up to attack and consume human flesh. Romero called these creatures “ghouls,” after the Arabian folkloric ghuls (probably via the Gothic novel Vathek or pulp work inspired by it) that “wander about the country making their lairs in deserted buildings and springing out upon unwary travellers whose flesh they eat” (Arabian Nights, Night 31). As I mentioned in an earlier blog post, the Arabian ghul may in turn derive from a type of Mesopotamian underworld demon called the gallu, who dragged the damned to hell, including Dumuzi, the god who died, went to hell, and rose again. That modern zombies hunger for brains also derives from the legend associated with ghouls, who previous to Romero had been considered living humans possessed by evil spirits. As Elliott O’Donnell described in 1912, “A ghoul is an Elemental that visits any place where human or animal remains have been interred. It digs them up and bites them, showing a keen liking for brains, which it sucks in the same manner as a vampire sucks blood.” That Romero’s ghouls were corpses derives from Romero’s commercial need to alter Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend, a book about vampires, significantly enough to avoid copyright violations. The undead nature of the creature is a legacy left over from Matheson’s original. But once that connection had been made between the (living) ghoul and the (corpse) vampire, the modern zombie appropriated the iconography and the mythology associated formerly with vampires. The zombie took on the unceasing cannibalistic cravings, as well as stories about the existential sadness of seeing a loved one transformed into a Creature. From the earliest folkloric vampires (not Hollywood’s version), the zombie also borrowed the rotten corpse shape, as well as the iconography of rising in a shambling, half-aware way from an unhallowed grave. Even the method of dispatching zombies—destroying the brain stem—is merely a scientific gloss on actual vampire-hunting techniques of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which involved decapitating the alleged vampire corpse and destroying its body. (Nor were zombies the only creatures to do such borrowing; Boris Karloff’s portrayal of The Mummy, in its early scenes, follows much the same pattern, and later mummy movies would make mummies essentially zombies with better wardrobes. Much earlier, Mary Shelley was conscious of vampire folklore in creating the risen corpse-creature, the Frankenstein monster, whose portrayal by Karloff in Frankenstein helped define the shambling, stumbling gait of future walking corpses in movies.) The only real difference, in a practical sense, between folklore vampires and zombies is number: The zombie operates en masse. But even this is an accident of history. Romero’s zombie hordes exist because Richard Matheson depicted his hero trapped in his house by herds of mutant vampires, and Romero wanted to replicate this key scene with his variant monster. But even this was not without precedent: Consider the group of skeleton warriors who attack Jason and the Argonauts in the 1963 film of the same name, or their clear inspiration, the terrifying skeletal warriors of Pieter Breughel the Elder’s Triumph of Death (1562, drawing on earlier Danse Macabre imagery), which would today pass for a Zombie Apocalypse. So, you may ask, why do I dislike zombies if they incorporate so much history and culture? Well, it’s because they don’t incorporate it as much as they destroy it. They are the fast food of monsters. They take the rich history of European and Near East folklore associated with the terror of death and homogenize it into a generic product completely devoid of character or color. All defining traits of the earlier monsters are gone; any trace of the supernatural (and all that this implies) is wiped away. The zombie is just a corpse, a husk, a shell. As a monster, it is a void. As a storytelling device, it is a deus (corpus?) ex machina. It is literally and figuratively empty.

5 Comments

Jim

10/23/2012 06:48:24 pm

What do you think of the more recent fast moving zombies such as in 28 Days Later (2002 - not undead but infected... still zombies), the Dawn of the Dead remake (2004), and the upcoming World War Z (2013). The fast moving zombies have also made it into video games (Left 4 Dead series). These zombies tend to behave in a more predatory animalistic fashion then the shambling old zombies of the past. To me the old zombies seem to tap into the same emotions that the 'inevitable assimilation' monsters do - such as the cybernetic Borg of Star Trek Next Generation and parasitic aliens from The Pupet Masters, while the fast moving zombies are more about the fear of devolving into something more base and animalistic - such as The Island of Doctor Moreau or Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. In any event, I'll take just about any zombie movie over the ridiculous glittering vampires of Twilight. Talk about the destruction of a rich folklore!

Reply

10/24/2012 10:35:21 am

Honestly, I think the "fast zombies" are a result of producers' decision that attention spans are short and the monsters need to move faster to keep the action up. Ditto the increased violence of "fast zombies."

Reply

Jim

10/24/2012 02:18:03 pm

You have a valid point on shortened attention spans. It is probably the motivation behind some of the "fast zombies", but I don't think it accounts for all of them. A fast moving monster does not necessarily mean that the movie is paced for an audience with ADD. The xenomorph in the original Alien was very fast moving, but the movie itself was very suspenseful with long, tense, 'low action' scenes punctuated by brief high action encounters with the Alien. In addition, rendering traditional monsters in a more animalistic fashion is not limited to zombies. 30 Days of Night treated vampires in much the same way, although in this case the ADD argument probably holds. 10/25/2012 01:35:28 am

It's probably difficult to separate the increase in "animalistic" villains as cultural response from an increase due to loosening standards and a general increase in explicitness in all kinds of media. Today, a thoughtful, suspenseful horror movie is considered "art" cinema unless it trafficks in extreme torture and cruelty.

Jim

10/25/2012 02:47:17 am

Thanks for taking the time to respond to my previous posts. I enjoy reading your blog a great deal, and I appreciate the fact that you take the time to thoughtfully reply to your readers.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed