|

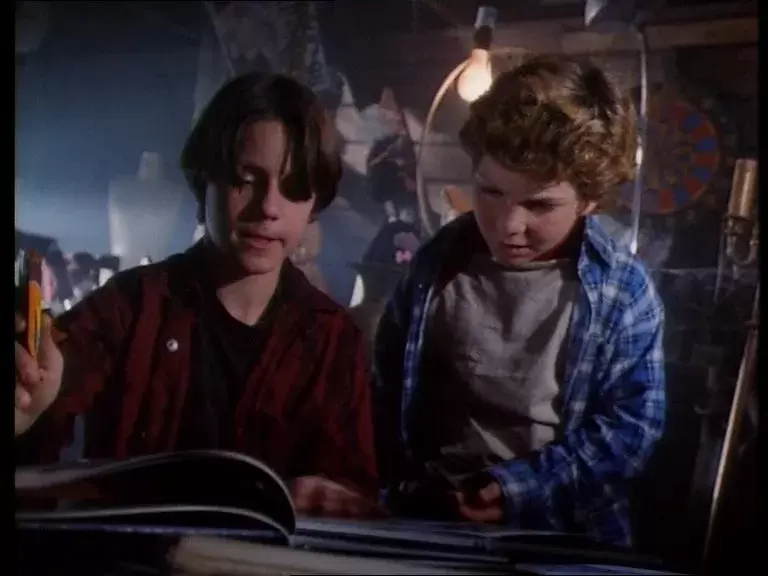

Note: This essay is cross-posted in my Substack newsletter. This past weekend, Tom DeLonge, the punk rocker and UFO media entrepreneur, released his first feature film, Monsters of California, direct to streaming. DeLonge served as both director and co-writer of the film, which follows a teenage boy and his friends as they investigate conspiracies about aliens and the paranormal around San Diego only for the hero to achieve New Age enlightenment through realizing his place in the cosmos. Indifferently acted and roughly written, the movie is an amateurish production all the way around, the New Age equivalent of those Christian “movies” that badly approximate a Hollywood production. Like those evangelical films, Monsters also has a spiritual message, that all is consciousness, we are but specks a pantheistic tapestry, and that “advanced” aliens are our teachers and guides toward enlightenment. By coincidence—though I suspect DeLonge would argue otherwise—a little while back, I saw that the streaming platform Tubi (and, also, YouTube and Amazon Prime) had recommended Eerie, Indiana, the 1991–1992 NBC comedy following the adventures of a teenage boy and his best friend as they investigated conspiracies, including aliens and the paranormal, in the titular small town. Although the show ran only eighteen episodes (plus one that remained unaired until syndication), it surprised me how well I remembered my ten-year-old self loving it, despite not having seen it in decades. (I vaguely recall having seen an episode or two a second time in a later syndication run.) Revisiting the series as an adult, now that I am older than even the actors playing the parents, is an eerie experience of its own, but what truly surprised me is both how richly literate and how dark—and darkly political—the series was beneath its campy façade of being The Twilight Zone for tweens. Eerie, Indiana centers on Marshall Teller, a thirteen-year-old boy played by Omri Katz, who is best known today as the protagonist of the 1993 Disney film Hocus Pocus. While filming Hocus Post, Katz had become quite troubled and was often too intoxicated to perform, but here he exudes an earnest, open-faced charm that makes his opening narration almost plausible: My name is Marshall Teller. I knew my hometown was going to be different from where I grew up in New Jersey. But this is ridiculous. Nobody believes me. Eerie, Indiana is the center of weirdness for the entire universe. Item: Elvis lives on my paper route. Item: Bigfoot eats out of my trash. Item: Even man’s best friend is weird. You don’t believe me? You will. As we learn in drips and drabs throughout the series, Marshall’s father Edgar, a staunch Republican, decided to move his family from the increasingly liberal New Jersey (which would vote Democrat in the upcoming 1992 presidential election) to an all-white town in the more reliably conservative Indiana, largely over the objections of his more liberal wife Marilyn, who chafes at small town America’s conservative values (and in a late episode even delivers a tirade against Eerie’s all-male power structure) but nevertheless submits, under the theory that such communities are wholesome and thus better for kids. The elder Teller works for a megacorporation that approved the relocation because—in a sly reference to the classic Middletown study of Muncie, Indiana—Eerie is statistically the most average town in America and the perfect location to test market inventions. Nevertheless, it becomes apparent to Marshall that the sitcom-style small town aesthetic and the embrace of conservative values—commerce, low taxes, and human sacrifice—is only the thinnest of veneers over a deeply troubling reality. Housewives preserve their youth by sleeping in giant tubs of ersatz Tupperware. The school nurse brainwashes students to behave. A TV remote transports kids into a television set. A vengeful tornado strikes the town on the same day each year. This is where the show splits between the cartoonish surface reading and the much darker subtext. On the surface, the troubling reality behind the Donna Reed façade is a colorful and bizarre set of enjoyably weird happenings that would have been at home on Tales from the Darkside or Tales from the Crypt. Beneath that surface reading is a caustic critique of the stifling, abusive culture of “traditional” values promoted by the likes of the Moral Majority and the Christian Coalition. When the townsfolk speak of “liberals” the way one would monsters and hector Eerie’s “last remaining liberal,” or fall for the soul-sucking deceptions of a demon named “The Donald,” it’s clear that Eerie, Indiana wants us to understand that the wholesome façade of small-town America hides something so dark that it has to be disguised with science fiction even to contemplate. Consider Marshall’s best friend, Simon Holmes (Justin Shenkarow), a nine-year-old who is the only other person to believe that Eerie is weird. “I let him hang around because his parents don’t seem to want him around,” Marshall says. But it’s more than that. Although none of the adults ever intervene, they all recognize that Simon’s parents are neglecting him, prompting the Tellers to provide him with food and a place to retreat from his parents. The one time we see inside Simon’s home, we learn his mother is rarely around and we hear his father having loud sex with an apparently much younger woman, while ignoring the needs of his two kids (Simon has a rarely seen younger brother even the show forgot about). It’s difficult to imagine a kids’ show doing a scene like that today. NBC declined to air an episode about another boy who was explicitly the victim of child abuse in what the show itself describes as a generational cycle of fathers abusing sons. That episode debuted two years later, on the Disney Channel. Depictions of abuse recur with stunning frequency for such a short run. A mother emotionally and physically stunts her sons to keep them close. An alcoholic father drives away his wife and abuses his daughter to the point that she goes mad and supernaturally imprisons and tortures him. An abandoned boy turns to a life of crime. Even Marshall’s parents, depicted as “good,” if hapless, are neglectful and happily send him off with various potential abusers and strive to rein in his individuality in the name of normalcy. In the episode “Mr. Chaney,” the surface level supernatural story hides disturbing subtext. Marshall is unwittingly chosen the town’s “Harvest King” and must go camping with a local agricultural power broker (played by Stephen Root) to complete an ancient ritual that will guarantee good harvests “and low taxes.” It’s a very literate episode for a kids’ show—the mythology is drawn wholesale from The Golden Bough, right down to the provision of gifts to the “king”—but the way the elements are recombined reveals something more than a simple horror story. Although Root’s transformation into a werewolf and subsequent comeuppance are played for laughs, what we see on screen is a group of powerful men who conspire to groom teenage boys and let a well-connected pedophile take them out into the woods and prey on them, which everyone agrees to pretend doesn’t happen, just like uncounted Boy Scout leaders were actively doing at the time. The abuse could be played for laughs because, by and large, it happens to boys. (When the rare girl is the victim, she is not the butt of the joke.) Eerie, Indiana was a very male show, made by men for boys. It fell at the tail end of the long history of boys’ adventure fiction that took place in a world composed largely of boys and men, into which girls and women were interlopers, either fleetingly encountered angelic love objects or hectoring antagonists. Perched on the edge of puberty, this heavily male focus, combined with the show’s explicitly camp aesthetic, invites queer readings. For most of the series’ run, Marshall is overtly concerned with attracting the attention of other males, seeking to become close to teen boys he perceives as cooler than him. Multiple episodes revolve around his inability to become one of the guys due to some inexplicable difference. In “Heart on a Chain,” the viewer can viscerally feel the show realizing that it almost took the theme too far. In that episode, Marshall befriends Devon, a super-cool classmate modeled on James Dean (down to the “live fast, die young” catchphrase). Both boys become enamored of Melanie, a dying young girl who needs a heart transplant. Devon dies in a bizarre accident and Melanie gets his heart (and is back at school the next day!). Her personality changes, and she now acts and talks just like Devon. An awkward transition halfway through indicates exactly when episode writer (and series co-creator) José Rivera must have realized the problem with having Marshall becoming even more attracted to the girl when she was possessed by the dead boy that he was also emotionally invested in and mourning. Or, to put it in starker terms, he was attracted to a girl with the soul of a boy—a girl who’s a boy inside. I think you get the idea. The possession plot suddenly drops without explanation along with most of Marshall’s ardor, though no one seems to have told the costume department, which still dressed Melanie in Devon’s clothes. The camerawork makes sure to inform us that Devon’s spirit is somehow randomly inside a graveyard statue at the time that Marshall kisses Melanie. You don’t want impressionable kids thinking that Marshall was kissing a boy in a girl’s body! As problematic as some of the dated 1990s attitudes toward sex and gender might seem today, the one place that Eerie, Indiana shines brighter than most series on similar subjects is its wealth of references not just to classic supernatural stories but to the rich mythology of pseudoscience and the occult. Rivera grew up on The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits, but in Eerie, you see the deep influence of In Search Of… and the paperback occult and fringe books of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Episodes throw out references to everything from Elvis sightings to De Loys’ Ape to the Tunguska Explosion of 1908 without a word of explanation, letting the vast lore of the weird and bizarre mingle with the fictitious story du jour to give texture to the tales, much the way H. P. Lovecraft embedded allusions to real gods and monsters amidst his fictional creations. It doesn’t always work—the silly tone often undercuts the effect—but when it does, it’s easy to see why when I was ten it captured my imagination. I suppose the final episode, “Reality Takes a Holiday,” might be the most memorable. Formally audacious for a kids’ show, it finds Marshall terrified to discover himself in the place of Omri Katz filming Eerie, Indiana, and the intended victim of a murder plot. It blew my mind as a kid, but it’s also a comedic riff on a Twilight Zone episode, “A World of Difference” (S01E23). For my money, the best episode is also the most subtle. “Marshall’s Theory of Believability” (written by Matt Dearborn, the creator of Even Stevens) is a thoughtful meditation on the reasons that we want to believe in the weird. A self-described expert researcher of the paranormal, Dr. Zirchorn, arrives in Eerie with a traveling museum of the “para-believable.” It’s stuffed with exhibits familiar to any fan of Ancient Aliens, and Marshall and Simon are first in line. The boys worship Dr. Zirchron, and Marshall dreams of growing up to be like him, a cultured, sophisticated researcher traveling the world, solving mysteries, and collecting evidence of the paranormal and extraterrestrial. But it’s equally evident that much of Zirchron’s appeal comes from Marshall’s desire to escape—to escape from the oppressive, repressive weirdness of small-town conservative social strictures, to escape from the oncoming doom of dull, middle-class adult existence. The weird is the promise of something that lies outside of the rules, outside of conformity. “Marshall’s Theory of Believability” navigates through these complex waters with remarkable subtlety for a show aimed at ten- to twelve-year-old boys. Dr. Zirchron is a fraud, a con man trying to sell the town a fake alien artifact to pay his ex-wife’s alimony. Marshall discovers this, and he’s devastated. His dream is crushed. He chooses to expose Dr. Zirchron and save the town from a financial disaster. But afterward, he and Dr. Zirchron discover that the “fake” alien probe lights up and takes off into the sky. It was real after all. The episode does not treat this as a vindication of Dr. Zirchron. He’s still a fraud, his “para-believability” nothing more than a con. But Marshall finds in witnessing the alien object a renewed sense of awe. Despite the object leaving no evidence behind, Marshall says that witnessing its ascension gave him back the ability to believe in the weird—and to have hope. “It allowed us to believe in the unbelievable again.” That hope might be cloaked under the supernatural, but it is nevertheless obvious that it is the hope for a better life somewhere beyond Eerie. Indeed, in the final episode of the series, Marshall sums up his philosophy by saying that he would not follow the script society gave him but would “demand a rewrite.” When I was ten years old—I turned eleven a week after the last episode aired—I wanted to be Marshall. I wanted to investigate mysteries and find the truth, to be the one who could see through the veil. I, too, collected artifacts and evidence and chronicled what I learned. I suppose, in many ways, I still do. And like him, I wanted to escape the small town where I lived. I didn’t quite realize at that age the reason I wanted to leave. I was too young to fully understand why I was different than other boys and what that would mean for me. But I could understand the supernatural and the weird.

After producing thirteen episodes, a failed retooling sought to move the show away from standalone mysteries to a more serialized structure with additional (and abrasive) recurring characters. Eerie, Indiana was canceled following six noticeably weaker episodes, ending in the spring of 1992. It went on to have a remarkable afterlife, first in reruns on the Disney Channel in 1993 and then to renewed popularity in 1997 when it ran on Fox Kids Network. By that point, I had matured beyond the show’s demographic, so I never saw a tangentially related inferior 1998 Fox Kids reboot, Eerie, Indiana: The Other Dimension, which placed Eerie on a fault line between parallel dimensions. Nor was I aware of an apparently long running series of late 1990s middle grade novels that followed the further adventures of Marshall and Simon—though I think I recall seeing one at a book sale years ago. Nevertheless, revisiting Eerie, Indiana as an adult, it surprises me how much of it I remembered quite well, a testament, I suppose, to the power and influence of art. I certainly didn’t fully appreciate everything the show was saying when I was ten, but it prepared the way. A year after its cancelation Fox debuted The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr. and The X-Files, two shows that were both deeply enmeshed with the weird and shared more than a little thematic DNA with their junior league predecessor, and I loved them both. I’m not sure it was fully to my benefit that my early influences were so weird. But, as Marshall Teller said, it gave me a reason to believe in the unbelievable—or, at least, in dreams that seemed impossible.

12 Comments

The same Tom DeLonge ??

10/10/2023 05:12:47 pm

The same Tom DeLonge - the buddy of Luis Elizondo - who introduced the world to Flir, Gimbal and Gofast - and the founder an entertainment company called To the Stars, Inc. which, in 2017, he merged into a larger To the Stars Academy of Arts & Sciences.

Reply

cicely

10/10/2023 06:02:03 pm

I loved that show!

Reply

Daniell Ellison

10/10/2023 09:29:27 pm

What is the root cause of your palpable anger at anything UFO related?

Reply

Gilbert grape

10/13/2023 10:25:40 am

Charlatans peddling nonsense to the gullible under the guise of seeking the truth tends to trigger people with an IQ above room temperature and internet access.

Reply

Daniell Ellison

10/15/2023 02:34:49 pm

Is that so?

GG

10/20/2023 12:33:50 pm

Those accomplished people generally don't operate their own online forums where they are free to express their thoughts to a popular audience. Those that do quite frequently offer a combination of intellectual and emotional responses to stupidity. Those that can provide a solid intellectual basis for their anger tend to find a receptive audience among those with an IQ above room temperature. Not so much with other demographics that consume online content who are unable to debate the intellectual basis and so must settle for tone policing. Cope better.

An Over-Educated Grunt

10/14/2023 10:26:41 pm

Gets old seeing unsupported dumbassery followed up with "YoU cAn'T eXpLaIn ThIs!"

Reply

E.P. Grondine

10/11/2023 08:10:00 am

Good morning, Jason -

Reply

kent

10/19/2023 06:18:36 am

Can't happen soon enough. Enjoy the fall, the landing will handle itself.

Reply

Kent

10/11/2023 08:48:48 am

"All is consciousness" to "pantheistic" is a huge enough leap that let's see your work. You're making a category error here I think.

Reply

Joseph

10/13/2023 04:31:51 pm

Hello Jason,

Reply

Kent

10/16/2023 04:12:12 pm

Watching "William Shatner Meets Ancient Aliens" S16 ep06, 2021.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed