|

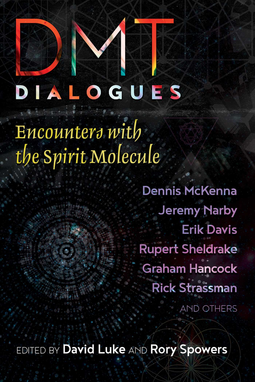

DMT Dialogues: Encounters with the Spirit Module David Luke and Rory Spowers (eds.) | 352 pages | Park Street Press | Aug. 2018 | ISBN: 9781620557471 | $18.99 On Saturday, I wrote a bit about Jason Silva’s recent interview with the Daily Grail discussing awe, wonder, and the connection between altered states of consciousness and the experience of the sublime. I was somewhat critical of Silva’s approach, but after I published my post, Silva contacted me to talk about some of the issues involved. We had a productive and interesting conversation, and I was impressed that he was well-informed and thoughtful in considering some of the more challenging areas of the quest for the sublime. That’s really unusual for a TV personality. Trust me on that. I went to school with enough of them, and have met still more. Silva and I likely won’t agree completely, but it was a refreshing change from the usual round of vitriol and threatened lawsuits from the people whose work I’ve discussed on this blog to have an actually enjoyable conversation. Be sure to check out Silva’s YouTube channel, Shots of Awe, where he posts his thoughts about truth, beauty, science, and philosophy. His recent video about psychedelic therapies and mental health is particularly relevant because it is a more rational and practical version of the topic of the book under review today.  Since Silva’s brand is inspiration, I found a bit of inspiration in our discussion to take on related topic that is usually a bit beyond my purview. An upcoming new release called DMT Dialogues: Encounters with the Spirit Molecule, due out in August, is an edited volume with chapters by a number of prominent figures in the nebulous field of “consciousness” studies, including Dennis McKenna, Erik Davis, Rupert Sheldrake, and Graham Hancock, originally presented at a British conference in 2015. The theme of the volume is ostensibly the mysteries of N,N-Dimethyltryptamine, a hallucinogenic substance best known as the active ingredient in ayahuasca, a plant used in South American shamanic rituals and in New Age spiritual questing. But the actual content of the book is weirder, focusing as it does on whether taking drugs can turn our brains into Wi-Fi hotspots to connect with space aliens or transdimensional godlike beings. This is an extreme, even fantastical form of what Silva had described as the therapeutic value of psychedelics. The conference speeches offer a raft of unusual, Romantic, and at times irrational hypotheses to explain the visions experienced while tripping on DMT. These hypotheses include, in no particular order, recognition that our universe is a simulation, access to parallel universes via the multiverse, contact with spirit beings from an ethereal plane, contact with space aliens who engineered DMT to communicate across interstellar space, and Scientology-like interdimensional souls in “DMT World” who incarnate in human bodies. Oh, and of course mechanical elves. But all of these hypotheses share something in common. Their advocates take it for a given that an internal hallucinogenic experience cannot be confined to the random firings of the brain or the random release of brain chemicals and therefore must be connected to something larger and greater and more important. At heart, this is not a book about DMT. It is a quest for meaning in the cosmos by people who feel but cannot quite express the deep tension that exists between our emotional experience of the world as humans and the material functioning of the universe revealed by science. The foundational problem is one inherent in the scientific project. Everyone involved in the book recognizes science as important, powerful, and prestigious, but they all attack it, at angles. Science is predicated on methodological naturalism, which is the assumption that the universe operates from material causes according to natural laws. While this assumption does not preclude the existence of the supernatural per se, it does mean that science inevitably explains the operations of the universe in material terms, shading heavily into outright materialism. Since the Victorian era, philosophers and scientists alike have recognized that the ability to understand reality without reference to God or the gods provides an essential argument for atheism. And those who quest for visions and omens and portents, and who want to speak with gods and angels and spirits, are deeply upset by the possibility of a material cosmos and yet find science so compelling that they cannot embrace traditional modes of faith. The reason for that can be found in the offhand references advocates make to their concern about finding meaning or avoiding meaninglessness. In an atheistic cosmos, entirely made of matter and energy, there is no objective meaning, only a subjective one. I am not declaring that this is the actual universe we live in, but it is the one that the book’s authors fear. Without some sort of supernatural architecture to lay down the universe’s eternal law and declare our actions good or evil, the only meaning in our lives is the one we assign to it. Our visions are just hallucinations, our experience of the sublime but a bath in brain chemicals. Love and laughter, connection and camaraderie are but transient feelings produced by evolutionary forces and neurotransmitters. When we are gone, neither the stars nor the planets nor the cold gulfs of space will care that these flashes of electricity passed between our neurons. That leaves us as individuals to develop our own meaning and to claw from the icy edges of the infinite a sense of purpose and a reason to be. Not everyone is able to do this. For many, it is terrifying to contemplate the possibility that in a real sense, we are alone. Descartes struggled to justify how we can know we are not all that exists, hallucinating the world beyond us. Early explorers pushed to the edges of the Earth in hopes of learning that we are not alone in our community, country, or continent. We scan space looking for others beyond our species. And the men—and they are mostly all men—writing in this book take drugs in the hope of breaking the walls of reality to peer behind the veil and prove to themselves that there is meaning in the world through recourse to the supernatural, that at some ultimate level they are not alone. One of the book’s editors admits this himself, writing that the purpose of these papers was to explore how “the synthesis of Science and Spirit, and even direct experience of the divine, [will] reshape our worldview.” He suggested that DMT research will prove that consciousness is an independent supernatural force in opposition to matter, but what he really means is that he hopes to go back before science had undermined spirit, to a time when the world was alive with animist forces. It is, at root, a fantasy. After all, this is a book where one speaker, super-rich property developer Anton Bilton, who hosted the symposium, expected his audience to take seriously his belief that while tripping “in the astral” (presumably the astral plane of spiritualism) he met Hellboy (i.e., “a monstrous, horned, ten-foot-tall demon … his huge muscles rippling under his red leathery skin”) who told him in foul-mouthed British English that “you fucking humans” are too “bloody arrogant” before grabbing him by the neck to show him visions of the End Times. Bilton, who seems to lack a sense of the ridiculous, called this “more real than real” and said its reality pushed his “intuitive truth button.” The demon lectured him on the insignificance of humanity before the many bureaucratic hierarchies of angels and demons, and I wondered why exactly all these superior beings spend their free time haranguing drugged up humans. Is it similar to Thomas Aquinas’ cruel idea in Summa Theologica (supplement to Part 3, 94.1) that the sport of heaven is watching the torment of the damned? (Cf. Tertullian, De Spectaculis 30 and Augustine, City of God 20.22.) I have spoken many times in the past of my own experiences seeing hyperreal visions in an altered state of consciousness when I was a child, brought on by illness and sleep deprivation. My visions were just as real but utterly absurd. At one point I sat amidst glowing blue vines and iridescent purple flowers with a frog wearing a leather jacket and a 1980s punk hairdo. Later in life, I met demons between wake and sleep, but they dissolved before my touch… because they weren’t really there, at least in no material sense. Yes, the visions felt real, but in what sense were they actually real? That question is perhaps philosophical, but lacking any testable way to distinguish between contact with another realm and a hallucination—they never seem to deliver any quantifiably useful data—it is ultimately a matter of faith, not science. (The conference participants idly speculate that perhaps they could ask their own demons for a fact not yet known to science to prove their otherworldly origin, but they never try.) The core issue is the question of how to evaluate a set of indisputable facts. It is true that consuming hallucinogens such as DMT will induce an altered state of consciousness in which the user will see images from a storehouse of shapes and sensations that appear universally in the human mind, regardless of culture. But that is where the indisputable facts basically stop. How those shapes and sensations are interpreted vary according to cultural expectations, as David Lewis-Williams described in The Mind in the Cave. For example, a jagged line might appear a snake or a lighting bolt. A humanoid figure might seem to be a god, a demon, an ancestor, or a loved one. Lewis-Williams, taking the approach of methodological naturalism, explains these visions in terms of the conscious mind attempting to make sense of random internal stimuli derived from the evolution and architecture of the brain. But if you do not accept a material explanation, then it might also be valid to interpret these visions in terms of the supernatural or the divine. This, however, becomes problematic because the supernatural cannot be proved using naturalistic methods, and because it becomes challenging to demonstrate to someone who is not a believer how we can distinguish between the supernatural and Lewis-Williams’s explanation, given that both yield identical appearances, and only one can be tested. The conference attendees dance around some of these issues, but they never consider, formally, whether their experiences might be nothing but meaning they have constructed from random stimuli and cultural conditioning. Bilton argues that the importance of DMT trips is that “entity encounters” are meaningful to the experiencer, and this might have been a useful point except that he then classified all types of entities, from aliens to fairies to “sexy succubi” as literal gods, and reality as “subjective.” He specifically complains that science (or “scientism,” the application of science to nonscientific questions) has crushed the supernatural out of existence. Another speaker railed against materialism and physicalism and tried to draw on premodern philosophy to wish them away. And yet at the same conference on the same day Bilton spoke, Dennis McKenna crushed the spiritual right out of the sacred to rapt applause from the same audience that had just acclaimed the opposite. McKenna attributed ancient Egyptian beliefs to DMT and entered into dialogue with an impressed Graham Hancock about whether the Egyptian “Tree of Life” was actually Acacia nilotica, a DMT-bearing plant, a claim Hancock found “a revelation … extraordinary!” Even in grasping for the otherworldly, they can’t help but try to cast it in the language of science to give the cover of the scientific to a quest for the profoundly unscientific—the spiritual. It probably means something that H. P. Lovecraft’s name came up in the discussions at the conference, with attendees wondering how Lovecraft could have “known” in his story “From Beyond” that stimulation of the pineal gland gives access to supernatural entities, as they believe DMT acts on the body. The reference in Lovecraft’s story is to Descartes’s fanciful claim (extrapolated from Galen’s theories) that the pineal gland connected the soul to the body, but the conference attendees, who care not for literary analysis, instead declare that they cannot explain such a mystery and instead speculate whether Gothic horror and Theosophy both were drawing on a secret store of mystical knowledge from the dream world, alleging that Lovecraft gained all of his story ideas from dreams. The dream claims are overstated; they provided impressions and emotions, but the stories themselves were carefully constructed from a variety of traceable influences. In truth, Theosophy and weird fiction influenced each other, via fringe historical claims about Atlantis and Lemuria, driving one another to ever more extreme and bizarre ideas that eventually escaped reality altogether. Bulwer-Lytton’s science-fiction substance vril ended up in Theosophy, and their Venusian interstellar ships became UFOs. None of it was real, just a merry-go-round of mutual delusion. McKenna, Davis, and the rest said they pitied Lovecraft for being a materialist who refused to fully embrace the alternate dimensions of reality they think he accessed in his dreams. Many, many years ago, when I demonstrated that Lovecraft’s fiction was deeply connected to the fringes of science, archaeology, and history, many of these same people—particularly Hancock—were angry and offended. Now they openly discuss Lovecraft as a prophet. I’m not sure that this is progress. Writer Erik Davis is admirably blunt in admitting the underlying truth. He spoke of his concern about “modernity” and his worry that science “controls” knowledge and has “disenchanted” the world, and he explicitly claims that “materialism” is an enemy that the “spiritual” must conquer. Psychedelic drugs are, for him, a gateway to the old animist world before science and industry, before the stress of work and bills and politics. They are a silver key back to glories and freedom of childhood, when imagination made the world seem magical. Underneath some fancy claims about the occult and spiritual traditions, he implies that the drugs are hope against the darkness. “Psychedelics open up a space for new kinds of religious experience, for new kinds of mysticism, and for new ways of thinking about God.” I find that sad, to be honest. It seems like an admission of failure. At one point, neurobiologist Andrew Gallimore comes close to the abyss as he tries to interrogate whether the “DMT World” is “real” and whether the world outside our heads is “real.” He comes perilously close to solipsism, since it is ultimately impossible to prove conclusively to ourselves that anything exists beyond our own minds—reality could always be an illusion—but he pulls back by suggesting that DMT accesses “information” from a hypothetical other world that our brains reconstruct based on cultural input. How is this different from hallucinating and dreaming? Faith, I suppose. He claims that he can resolve all of the problems of mind and body by declaring reality subjective, a creation of our minds. “We need to basically forget about the objective world,” Gallimore said, if we want to accept the DMT world in our mind as equally real to physical reality. He even speculates that everything around us is a simulation or an illusion. But if our minds can create reality, then how do we know we are not all there is? Solipsism it is, then. Rupert Sheldrake speculates on the nature of God and whether DMT can connect us to God. He also talks about the fact that he believes that science and faith are both arguments from authority for all but the elite, since only a small number of people ever actively engage with their ideas at the granular level. Therefore, he concludes that argument and analysis are irrelevant to the understanding of reality and only “direct experience” can create deep understanding. This is less an argument for DMT than it is an argument for education. Hancock delivers a lecture on the similarities between DMT and UFO abductions, and he draws on a lot of bad data and old chestnuts drawn from ancient astronaut theories and ufology, from the “UFO” in Aert de Gelder’s Baptism of Christ to the Betty and Barney Hill abduction to the faulty Passport to Magonia of Jacques Vallée, attributing all of this not to the demonstrable influences on ancient astronauts and ufology (not to mention frauds) but to a supernatural realm of pure form. He never bothers to explain why we should assume that similarities between ufology, folklore, and DMT tripping should connect to an objectively real otherworld rather than an internal mental one; it is simply assumed. He cites David Lewis-Williams approvingly, but again claims that only a supernatural realm can adequately explain what would otherwise be seen as internal mental phenomena. “I’m not aware of anything in science that allows us to reduce hallucinations to changes in the brain activity that accompany them,” he says, omitting that nothing in science supports spirit dimensions of gods and monsters either. Hancock is an odd case in that he recognizes that his DMT trips are not “really” happening; instead, he attributes the impulse behind the hallucination to information leaking into his head from occult intelligences via a “secret door” in his mind. This seems to be a question of faith, though, insofar as such a dimension exists outside of physical reality. He says that he refuses to accept a material explanation because he can conceive of no evolutionary purpose for DMT visions. It does not occur to him that they could also be an accidental side-effect of other processes rather than a naturally selected development. But that would be because he is uninterested in evolutionary theory, despite opining about it. That’s why he speculates that aliens could have seeded the universe via panspermia and encoded DMT receptors into our DNA so we could communicate with them across space and time. However, he said he prefers parallel universes to ancient astronauts. At the end, DMT researcher Rick Strassman said that he started his research assuming that DMT experiences were simply hallucinations, but he discovered that this was unsatisfying because users didn’t want to share with him their darkest secrets if they sensed that he thought they were seeing things. So, he began to act as though the experiences were from another reality, and then his research subjects talked his ear off about their trips. He understands that getting to the nature of the objective or subjective reality of a DMT experience is difficult, but he also claims to believe that the distinction between the real and unreal is “facile.” He cites the Hebrew Bible as a guide and argues that its “sophisticated” view of religion provides an organizing principle that can help us find the divine reason behind tripping balls. He swirls around an ecstatic acceptance of Biblical prophets as experiencing altered states of consciousness, and he suggests that prophets enter the DMT dream world, which he claims operates under Biblical principles such as “the Golden Rule.” This is best known as Christ’s Great Commandment (Luke 6:31), but here Strassman attributes it to Judaism (presumably Leviticus 19:18, 34), which is for him the objectively correct faith (well, he calls it “ethical monotheism”) because it matches his DMT experience. It does not occur to him that DMT experiences might draw on preexisting Judeo-Christian cultural beliefs operating through the believers’ minds. It is a strange speech, but an appropriate place to draw this discussion to a close since it returns us to the ultimate origin of the quest for another world—the effort to seek the divine. Strassman brings it back to the beginning, before Einstein and Darwin and the Enlightenment, when God the Father sat unchallenged on the throne and we never needed to think about anything because the answer was always God. “This God existed before, and will exist after, cause and effect,” Strassman said. But it is telling that he needs to appeal to psychedelic science to justify God’s existence in a modern, more secular era. Formally, DMT Dialogues is a transcript of the conference, with each speaker’s speech given unrevised and verbatim, followed by audience discussion. I am impressed that anyone took such time to transcribe the whole thing word-for-word, but the downside is that the book is occasionally choppy and confusing, since unrevised spoken language rarely makes for a smooth reading experience. As a record of what true believers say to one another when no one is watching, it provides valuable insight into the cognitive processes of a group of people who want to use science to attack the findings of science in the hope of justifying their belief in the spiritual. But as either science or spirituality, it is an infertile hybrid, reducing the sacred to alchemical formulae and the scientific to an ill-understood respect for its outward forms. DMT Dialogues is suffused with references to Theosophy, science fiction, horror movies, mysticism, and all manner of outré topics on the edges of the intellectual world. Reading it proves that the quest for DMT “entities” was never about the drug, or “scientific” questions of consciousness. It was always a cry against the overwhelming fear that God is dead and we have killed him. The conference attendees don’t want to be alone in an unfeeling universe, and so they have conjured a whole dream world to escape into. Whether you choose to join them depends on how you elect to handle the tension between the material and the immaterial, the physical and the spiritual, the objective and the subjective.

29 Comments

Scott Hamilton

6/12/2018 10:00:27 am

I suspect that humans have some sort of mechanism in our mind that lets us know that are hallucinations aren't real, even if they "seem" real. I had a hypnogogic dream once, and my waking thought wasn't "I need to kill that giant spider", it was "I'm thirsty." You'll see this kind of thing even in Whitley Streiber's Communion, where he wakes up thinking the house is on fire, and then he just goes back to sleep. So if the mechanism breaks down or is ignored, you get people thinking hallucinations are real.

Reply

Machala

6/12/2018 01:28:28 pm

"...I was so struck by how the people taking DMT just completely assumed their own hallucinations were real, to the point of not even acknowledging that other people's concurrent observations could have any validity."

Reply

Doc Rock

6/12/2018 10:31:02 am

Some of the published research on alleged UFO abductees has reported that, surprise, a common characteristic of such folks is that they score high in imagination and in other categories that might lead one to interpret a case of sleep paralysis as an abduction. In other instances there may be other factors at play when it comes to some people choosing to put a wild spin on something like sleep paralysis.

Reply

AAA

6/12/2018 11:42:09 am

Does science have any explanation what existed before the Big Bang?

Reply

Shane Sullivan

6/12/2018 12:30:15 pm

http://www.hawking.org.uk/the-beginning-of-time.html

Reply

Aaa

6/12/2018 12:38:53 pm

_All the evidence seems to indicate, that the universe has not existed forever, but that it had a beginning, about 15 billion years ago. This is probably the most remarkable discovery of modern cosmology._

David Bradbury

6/12/2018 02:35:17 pm

Try thinking of it as "an egg arose out of infinite chaos".

Uncle Ron

6/12/2018 04:10:18 pm

The information we can study concerning the beginning of the universe (the big bang), and all information about its subsequent evolution (its "history"), is "encoded" in the various combinations of sub-atomic particles* (i.e. atoms, planets. stars, light, the cosmic background radiation, humans, etc.) that we observe. If, as seems likely, the universe eventually collapses into a final singularity and then explodes again into a new universe, all the "stored" data is gone and the new universe will seem to have arisen out of nothing. This process can happen an infinite number of times and each time it is impossible to know what existed before the most recent big bang.

AAA

6/13/2018 02:38:19 am

_This process can happen an infinite number of times and each time it is impossible to know what existed before the most recent big bang._

An Over-Educated Grunt

6/13/2018 07:23:09 am

... And until Newton developed the calculus we couldn't explain acceleration properly. Are you saying that until the Principia Mathematica was published acceleration was supernatural?

Uncle Ron

6/13/2018 11:05:20 pm

You've missed the point. Once everything collapses into the final singularity ANY and EVERY previous combination of any particles is erased forever. A VERY loose analogy would be writing something on a blackboard and then wiping every single atom of chalk off the board and compacting it into a new piece of chalk. It is impossible to determine what was previously written on the blackboard.

An Anonymous Nerd

6/12/2018 06:19:25 pm

My understanding is that there are competing explanations but we don't know yet with any kind of certainty. So I guess the glib answer would be "not yet."

Reply

Causticacrostic

6/12/2018 10:14:47 pm

It's sort of a pointless argument anyway. If the basis of the debate is that "something can't come from nothing" then where would a deity come from?

Aaa

6/13/2018 01:28:28 pm

The answer is quite obvious. “Deity” and its creation ate one and the same. There is no separation. They have always existed and will always exist.

Americanegro

6/14/2018 10:32:35 pm

Are you fuckin' high dude? I've done enough psychedelics and enough academic work to peg you as a mildly challenged middle schooler.

Shane Sullivan

6/12/2018 12:32:38 pm

Hey, speaking of the Dennis McKenna and the Clockwork Elves, has everyone heard that one has finally been photographed?

Reply

Machala

6/12/2018 01:07:55 pm

Chortle, chortle !

Reply

Whoa

6/12/2018 04:25:37 pm

The declaration of the United States was founded on Reason and Secularism

Reply

iNDEED

6/12/2018 04:28:11 pm

The Bible and Judeo-Christianity is ONE BIG DRUGS ALMANAC

Reply

Clete

6/12/2018 05:02:01 pm

I think you were indeed fortunate to speak and have a rational conversation with someone that has a different opinion then you hold. It appears that Jason Silva has an open mind and is willing to listen to someone with different opinions and is willing to discuss them. That would indeed be refreshing.

Reply

La Raza Unida

6/12/2018 09:40:15 pm

We are winning. We now have legislation to secede and take back our land from all you non natives. Go back to Asia Africa and Europe or face deportation and genocide.

Reply

An Over-Educated Grunt

6/12/2018 09:59:57 pm

Come for the secession! Stay for the dad memes!

Reply

Huh? What?

6/14/2018 06:36:37 pm

Wait a minute, aren't you Mexis the descendants of the original genociders?

Reply

Kathleen

6/13/2018 08:51:12 pm

Hallucinogenic experiences are hallucinogenic experience. Set and setting account for much of the effect.

Reply

Mrs Grimble

6/19/2018 09:37:41 am

"The conference participants idly speculate that perhaps they could ask their own demons for a fact not yet known to science to prove their otherworldly origin"

Reply

Declan

7/5/2018 10:38:06 pm

Jason,

Reply

8/11/2018 01:54:28 pm

Jason, I was surprised when I finally came across this review, which includes an account of a talk I gave at this DMT gathering. Being familiar with your critical approach to the woo of our world--and the insightful things you say about Lovecraft--I wasn't surprised about your critiques of the book and many of the presentations. While I think you were being unfair in some cases, I share many of the same concerns you have with the ideas of Hancock, Gallimard, etc, who want so desperately for DMT experiences to be "real" that they overlook more reasonable possibilities. My approach is much closer to Narby's or St. Johns anthropological agnosticism.

Reply

8/11/2018 10:11:22 pm

Thank you for your comments, Erik. My comments above said that you see DMT as being used for spiritual purposes, but I did not assert or imply whether you considered these spiritual purposes to be objective or subjective, so I am not entirely sure what the problem is. Yes, your speech touched on many more positions than I could possibly summarize in a sentence or two (which is to say, that it wishes to have things both ways) and I highlighted an example of how your speech referred to a continuing theme in the volume, namely the alleged spiritual dimension of being in an altered state of consciousness. But I will direct you to the remainder of the paragraph in which the disputed phrasing appears, where you talk about the "wonderful" use of "spirit" to describe DMT and speak about your satisfaction that the spiritual and the material might be unified through psychedelics. It is clear that you have a positive view of them, and therefore I read your analysis as supporting what you clearly believe is the positive aspect of DMT. It is hard to read your speech as accepting the idea that spirituality is an artifact of evolution, and in that spirit (so to speak) I don't think you are as balanced and evenhanded as you imagine.

Reply

Farid

2/25/2020 08:35:22 pm

I'm Azerbaijani. I do not know English well. I use translation software. I apologize for my mistakes.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed