|

I’ve completed reading Part One of Graham Robb’s The Discovery of Middle Earth, and it goes a ways toward rehabilitating some of the claims presented less convincingly in the preface and Chapter 1. At times, the remaining chapters of this part are fascinating, and at times they are infuriating. And out of nowhere, at the end of the section, Robb presents evidence that is actually interesting and somewhat compelling--maybe. There are a lot of caveats. Chapter 2 opens with complaints that museum officials in France are too infatuated with the Romans, followed the claim that Greco-Roman accounts of the Celts are biased (undoubtedly true) and misunderstood baptismal and other religious rituals as disgusting manners and unrestrained sodomy (less certain). Robb says that the Romans simply destroyed most Celtic roads, but we can infer they existed because Anthony Harding calculated that the carts used on them weighed too much and would get stuck in the mud. Harding, in European Societies in the Bronze Age (2000), wrote: Such vehicles must have been immensely heavy. If, as seems likely from the models and from surviving wheels, they contained around 1 m^3 of oak wood, they must have weighed up to 700 kg. Resting on wheel surfaces only a few centimetres across, they would all too easily become bogged down in mud, and it is unlikely that they travelled very far or very fast. (p. 167) Harding then goes on to describe traces of Bronze Age wheel ruts and roads, but I don’t see how this has anything to do with the Iron Age Celts, who moved in a thousand years later. Robb makes a good point that Caesar found bridges and roads of some sort when invading Gaul, though he wants us to simultaneously chide the Romans for exaggerating or fabricating bad things about the Gauls while we should take them literally in describing how fast the Gauls could travel (Bibracte to Longones—120 miles—in four days) to determine how hard the road surface was. He explains that the Gauls were so accurate in their measurements of distance that the Romans continued using Gallic leagues rather than Roman miles after the Conquest of Gaul. I checked standard texts, and most assert that the Gallic league was reintroduced after the third century crisis, with the reassertion of Gallic identity, and was primarily associated with the weakened late Western Empire. The source is Ammianus (15.11.7), writing around 350 CE, who explained that distances had begun being measured in Gallic leagues in a time he described as “now” (as in, the late Empire) and by the Gallic elite, not Romans from Italy: “This point is the beginning of Gaul, and from there they measure distances, not in miles but in leagues.” Archaeology knows of Roman milestones given in miles before 250 and in both miles and leagues afterward. This negates Robb’s claims. He talks next about the Gallic vocal relay system, which is given by Caesar (Gallic Wars 7.3): The report is quickly spread among all the states of Gaul; for, whenever a more important and remarkable event takes place, they transmit the intelligence through their lands and districts by a shout; the others take it up in succession, and pass it to their neighbors, as happened on this occasion; for the things which were done at Genabum at sunrise, were heard in the territories of the Arverni before the end of the first watch, which is an extent of more than a hundred and sixty miles. (trans. W. A. McDevitte and W. S. Bohn) Robb makes much of the phrase “per agros regionesque,” translated above as “through their lands and districts.” He wants us to consider this phrase odd (though it makes perfect sense to me) and instead read regio as a technical term for a sight line used in surveying and augury, which is the oldest sense of the word. Its meaning of “region” comes from the idea that a region was bounded by survey lines; however, I’m not sure Caesar’s passage makes sense if we alter it to “through the fields and survey-lines by a shout,” and in any case Caesar already said that the Gaul’s shout to one another, so what is gained by trying to force Caesar to confirm that they shouted in straight rather than crooked lines? I thought the point was the Caesar didn’t respect or understand the Gauls’ greatness.

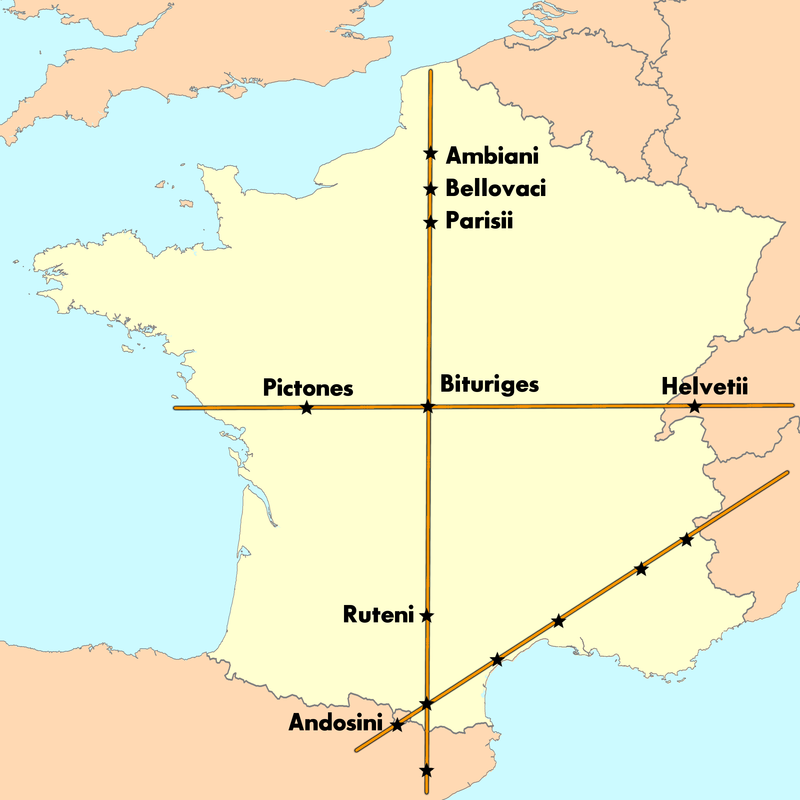

Chapter 3 brings us to the first chapter on the mystery of the name “Mediolanum,” which we have already seen means “the middle of the plane” according to most standard sources. I will treat this chapter together with Chapter 4, which continues seamlessly on the same subject. Robb again fails to provide an adequate reason to accept his innovation that Mediolanum should instead be rendered “Middle Earth” except that he appeals to Celtic mythology, with its Indo-European set of stacked planes (heaven, earth, underworld) and Indo-European analogs such as the Greek omphalos, or navel of the world. He rejects the etymology “middle of the plain” through the expedient of noting that many Mediolana are located on hills or mountains. I’m not sure that’s a good enough reason. I live in Albany, New York, which takes its name from the Duke of Albany, whose title derives from Alba, the Gaelic term for Scotland, in turn from the Indo-European word for white. And yet the city is not Scottish, nor particularly white. (Things around here are usually a dull gray.) Names need not be literal, especially if the fame of one Mediolanum led to imitators. Earlier etymologists suggested the word meant “full of fertility,” (mediad, harvest + lawn, full), or a central enclosure (Meadhon, middle + iolann, enclosure). Isidore of Seville (15.1.57) fancifully said the word meant “wool” (lanea) in the middle (medio). Robb then asserts (correctly) that the Mediolana (excepting a few large cities of that name) share one trait: None of them has any evidence of Celtic occupation, thus proving that they must be nodes on a Celtic communication/alignment survey route. That said, he may well be right that the name, at least in some cases, meant “halfway point” and was used as stopover station when traveling from one major settlement to the next, sort of like a rest stop on a highway. I can see this, but it doesn’t require any special solar alignments to make possible. I am also confused as to who exactly was living in these places that they continued to exist without leaving Celtic remains. At least some may have had Bronze Age occupations. On a map, he outlines 137 Mediolana (later expanded to 208 places with a form of “middle” in the name), which only shows how few align to his imaginary solar Via Herclea. They are scattered across Gaul like the spots of smallpox, clustered around geographical features and farmland. Admittedly, many of these do appear to be in straight lines, though I think a chunk of this is due to the settlements following France’s unusually straight rivers. I think, personally, that there may be something to the idea of small settlements named Mediolana serving as rest stops along ancient routes, but he wants us to play connect-the-dots without any archaeological evidence that the sites were Celtic, let alone part of an accurately mapped Gallic grid. He presents some charts with what he says are triangular coordinates surveyed by the Celts from one Mediolanum to the next, showing that in Picardy, each Mediolanum is about 29 km from the next, though varying from 28 to 32 km. It’s certainly interesting, but there are two problems: First, most of the place names are only attested from the Middle Ages, before which we cannot securely identify some of the sites as a Mediolanum or a middle place, and second, Robb does not include any other settlements in his calculations. Are there significant relationships to other cities and towns? Perhaps the distance reflects the amount of hinterland needed to support a settlement with produce and game, not a purposeful surveying of the land for map-making or religious needs? Robb addresses the latter question by noting that other types of settlements are more regular in their distance, largely due to economic needs. By contrast, he sees Mediolana as geodetic in nature. But here is my question: Did it have to be purposeful? Would simply striking out in a direction and walking 29 km (18 miles), a decent day’s walk for a merchant (and the exact length covered by Roman legions in five hours—the “regular step”), serve the purpose without a purposeful geodetic plan? In other words, might the nodes of the system have grown naturally based on a 29 km day’s walk without the need to have a master plan? I can’t claim to know, but Robb hasn’t made enough of a case at this point in the book to warrant more than the claim that this is suggestive. Is there a significance to 29 km? 29 km = 20 Roman miles = 13.4 Gallic leagues. I get the feeling that Robb found something interesting, but that it isn’t exactly what he thinks it is. Not that I know, of course. I have trouble though with the fact that even where a settlement is old, we don’t really know what its name was before Roman times. There’s no guarantee that all the “middle” places (now subtly expanded from the earlier focus just on Mediolana) were always called middle places, or that if they were that the name originates with the Celts. I will leave for later his assertion that the Druids organized continent-wide educational programs. He has separate chapters for that. Next he looks at Mediolanum Biturgium, a Celtic capital now called Châteaumeillant, which he takes to be an axis point on his Via Heraclea grid. A perpendicular drawn across Robb’s Via Heraclea through Châteaumeillant, he says, forms the “longest straight line that can be drawn through the part of the European isthmus known as Gaul.” In other words, the place is located just about dead center in France. His claim is true if you assume that the Celts made a political distinction between what we call France and what we call the Low Countries—which they didn’t—since the meridian running from Amsterdam due south to the Mediterranean crosses more land than the one Robb cites, ten km west of the Paris meridian. It also presupposes that the Celts were aware of the Mediterranean before the Celts actually filtered down to the south of France. Chapter 5 is a bicycle tour of the meridian line, with an emphasis on the continuities between Celtic religion and Christianity. Why then he chose to save for this light chapter the only convincing map he has yet presented, I can’t fathom. I admit to being impressed by a map of second century BCE Celtic capitals, which all align along three straight lines, six capitals on the meridian passing through Châteaumeillant. But this is, again, somewhat selective: there were fifty-something Celtic tribes in Gaul, and he has selected only fifteen capitals, the others presumably failing to match alignments. That said, the cities seem to fall on the line, and that is certainly a fascinating fact I am not able to immediately explain. I have redrawn most of his map below, with the meridian, the proposed Via Heraclea, and the perpendicular lines in orange, and the capital cities marked with stars, along with the tribal names Robb gives for most of them.

15 Comments

Only Me

11/15/2013 06:36:48 am

So, if I understand this correctly, Robb is choosing those sites that support his hypothesis, like the AA guys choose specific Mayan temples/Hopi villages to support the idea of alignment with Orion?

Reply

11/15/2013 06:40:26 am

It seems to be the case, but unfortunately, I don't know enough about which Celtic tribes had capital cities in 200 BCE to say for sure. Among the Mediolana, yes, he seems to be drawing best fit lines at will. I was looking at a map of Europe, and I was surprised how many sets of three or more (modern) cities I could connect with straight lines, too. Later in the book, he'll explain that Celtic buildings' corners were aligned to point to major European cities, such as London.

Reply

Only Me

11/15/2013 07:43:10 am

Can't wait for that explanation! I guess the Celts possessed mathematics and astronomical knowledge so advanced, they could predict the locations of those cities centuries prior.

Erik G

11/15/2013 09:10:31 am

I currently do not have access to my reference library, but is it possible that the 'Mediolana' places were actually relay stations on the cursus publicus, i.e. the Roman postal system? Roman couriers would have changed horses at each station, and were reputed to cover distances of over 150 miles a day. I don't remember if these were Roman miles or current miles. Augustus is supposed to have been the originator of this system, which lasted until well after the fall of the Western Empire, but I think Julius Caesar had used something similar both during and after the Gallic Wars. Did he adapt it from an existing Celtic system? I don't know -- I'd never even thought about it until today -- but as the Romans were quick to adopt for themselves anything from their enemies that worked well, I suppose it is possible. Assuming that these places were relay stations might explain the lack of evidence of Celtic occupation. Does Graham Robb make any mention of Roman milestones on the routes he discusses?

Reply

11/15/2013 10:48:07 am

Estimates do indeed place the night quarters for the Roman cursus publicus at about 20-25 Roman miles apart. Most histories, though, say that the Romans adopted the system from the Persians, but I can't imagine why the Celts wouldn't have had shelters for those traveling between villages, too.

Reply

The Other J.

11/15/2013 10:18:20 am

I'm mostly Irish, so I never yell in a straight line. It's science.

Reply

11/15/2013 10:52:46 am

I was trying to use longitude meridians to avoid having to account for the earth's curvature. It depends, I guess, on your tolerance for divergence: Robb generally gives about 1 degree of variance, and within that tolerance, Wroclaw, Vienna, and Zagreb are in a "straight" line (within 1 degree of longitude), as are Alborg, Hamburg, and Milan.

Reply

11/15/2013 10:54:22 am

But of course there's a list of cities by longitude: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_cities_by_longitude

The Other J.

11/16/2013 12:23:52 am

This is off-topic, and not sure if it's something you (Jason) would be interested in in the first place, but the History Channel -- not H2 -- aired a show called Bible Secrets Revealed, where they get into the problems of introducing interpretations and re-interpretations to suit socio-political ends -- much as you do with the AA and AU material. Except this time around, the show is jammed full of actual scholars (the usual suspects for religious studies -- Bart Ehrmann, Elaine Pagels, David Wolpe, Robert Cargill, Candida Moss, a lot more -- all names familiar to most people with even a cursory interest in the subject).

Reply

Dave Lewis

11/16/2013 11:03:04 am

My biggest disappointment with Bible Secrets Revealed was the inclusion of Reza Aslan among the talking heads. It seems that Aslan is trying to make people believe that he is a Biblical scholar.

Reply

11/16/2013 12:52:49 pm

Thanks... I hadn't seen that. I suppose I'll add it to the (endless) list of things to try to see.

Reply

11/16/2013 12:57:07 pm

Apparently there are some weird claims in the show, if this review can be believed: http://boldlionblog.wordpress.com/2013/11/15/review-history-channels-bible-secrets-revealed/

The Other J.

11/16/2013 04:22:39 pm

I don't think the claims made on the show are nearly as weird or deceitful as that writer suggests. First, he's clearly coming from a biased position and is pretty open about that, and for every case he brings up, he takes the most apologist interpretation as opposed to the most conservatively academic interpretation. That's his prerogative. 11/16/2013 10:38:02 pm

Thanks for the info. I figured that the blog writer's infallibility position was probably a bit wrong, and I appreciate the details of how the criticism was flawed. I guess I'll try to catch the show next time it's on and see for myself. And it is good that there is at least one show where real scholars comment on these issues rather than "alternative" and "fringe" types.

John Panneton

7/7/2015 11:03:54 am

Women produce only few large aggs and must spend years of their lives growing embryos with in their bodies and then nurturing the resulting babies.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed