|

Opposable Thumbs: How Siskel & Ebert Changed Movies Forever Matt Singer | Putnam | Oct. 2023 | 352 pages | ISBN: 9780593540152 | $29 Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert spent so long reviewing movies on television that, when Siskel died in 1999, I could not remember a time when I hadn’t watched them. They started their first review program six years before I was born (I’m 42), and as far back as I can remember, I can still picture my parents tuning in to hear about the newest movies—movies that, for the most part, they would only see on rented VHS tapes, months later. I tended to prefer Ebert to Siskel, not for any dramatic reason except that my local paper carried Ebert’s print reviews but not Siskel’s, so I felt like I understood his thinking more. Even when I was a teenager, Siskel & Ebert was still appointment viewing, and I recall setting extra time on the VCR to record the show when the local ABC affiliate’s sports coverage pushed it to odd hours of afternoon or overnight and we weren’t sure exactly when it would start. But over the years that followed, though a succession of hosts and format changes, hearing people talk about movies seemed increasingly less important, and I didn’t make extraordinary efforts to keep up with Ebert & Roeper or whatever the now-forgotten successors called themselves. I enjoyed Roger Ebert’s writing—he taught me something of how to effectively criticize—and I continued to read his reviews until his 2013 death, but the movies no longer felt important. After Ebert died, I mostly stopped reading movie reviews, and, frankly, I paid very little attention to movies. They are, today, just another form of media content, a TV episode of double length.

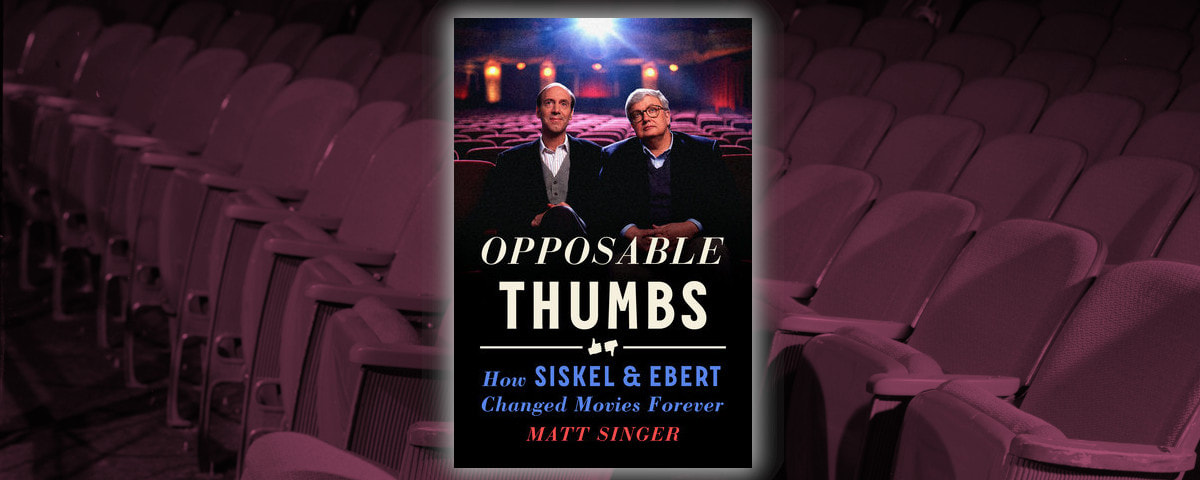

Matt Singer’s Opposable Thumbs: How Siskel & Ebert Changed Movies Forever tries to recapture some of the interest and impact that TV’s most prominent movie reviewers had in their heyday. It’s a breezy, nostalgic tour through a fading memory of a time when movies shaped culture and critics could shape movies. But Singer struggles mightily with the most basic question about the book, the same one Siskel and Ebert asked of movies: Why should I care? As I read Opposable Thumbs, I couldn’t help but think of Matt Singer as Gloria Swanson and his book as Norma Desmond, crying out, “I am big! It’s the pictures that got small!” In today’s world of Peak TV and franchise films designed to stream six weeks after their theatrical debut, trying to resurrect the greatness—not of movies, but of critics of movies—is a bit like trying to sell a history of Amtrak to passengers on a jetliner, or of Ma Bell to iPhone users. Opposable Thumbs bills itself as a joint biography of Gene Siskel, the longtime film critic for the Chicago Tribune, and Roger Ebert, the Pulitzer Prize-winning film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times. The pair became forever conjoined in the public mind because of the series of near-identical film review shows they hosted first on PBS and then in syndication, originally with Tribune Entertainment and later for Buena Vista Television, a division of Disney. However, the book focuses much more heavily on Ebert than Siskel, for reasons both personal and practical. Singer had both a personal and professional relationship with Ebert, whom he deeply admired, while Siskel left very little personal writing behind and his family provided next to nothing that might tell us something about his personal life. Opposable Thumbs is an enjoyable collection of anecdotes that will put a smile on the face of readers who recall with affection waiting to hear what the bickering critics would say about some hotly anticipated new release. It’s a time capsule from an era before the internet, and especially before social media, when one might still feel like hearing someone’s opinion was vital and exciting rather than exhausting. The 1980s and 1990s were the peak of “infotainment,” when happy talk ruled the airwaves and everyone lied about how wonderful every new product was. As Singer deftly notes, virtually no one other than Siskel and Ebert honestly said on air that a lot of media was utter crap. It was refreshing. But Opposable Thumbs runs its handful of insights into the ground. The book is organized around chapters that follow a rough chronology, but that chronology occurs mostly at the beginning and end of each chapter. In the middle are an exhausting maelstrom of anecdotes drawn from across the critics’ decades of working together, haphazardly strewn about and sometimes repeated multiple times. The same phrasing, the same points, and the same assertions recur with numbing frequency. The chaotic collection of stories follows no fixed chronology, and their atemporal placement saps any sense of narrative momentum from Opposable Thumbs. (Michelle Howry, the Putnam editor who oversaw the book, should have used a much stronger hand to cull the repetition and shape a narrative from the anecdotes.) There is no actual story, no real drama, no forward momentum, only a constant cycle of two men doing the same thing the same way until one of them died still doing the same thing the same way. This is not the kind of book in which the author took any great pains to dig up material that the families of the two critics wouldn’t want to see in print, which limits its utility even as a history of Siskel & Ebert. (The closest we get are previously published anecdotes about the critics’ love of big boobs and efforts to rig their schedules to be the one to interview sexy women.) Indeed, Singer is unabashedly a cheerleader for Siskel and Ebert, each of whom he considers (as we hear dozens of times in the book) the “kindest, bravest, warmest, most wonderful human being I've ever known in my life.” No, wait… That’s the Manchurian Candidate. Singer considers them the greatest, smartest, most important, most influential, and most famous movie critics who ever lived. You know that because he says it approximately one hundred times. By the time you’ve finished Opposable Thumbs, you’ll be as brainwashed into believing it as Frank Sinatra in Candidate, simply through sheer repetition. Look, I liked Siskel & Ebert, and its stars were certainly were major celebrities of the late twentieth century (especially on the talk show circuit), but arguing that it was the TV equivalent of an Enlightenment salon or that the two critics were great philosophers is a stretch—especially with so little to back it up. For example, Singer credits Siskel and Ebert with being the first nonfiction pair to bicker on television, to whose influence he attributes all of cable news and sports coverage. But Siskel and Ebert weren’t the first twosome to garner high ratings for fighting and insulting each other on TV. That dishonor is more typically awarded to Gore Vidal and William F. Buckley, Jr., who scored boffo ratings for their acrimonious but erudite ABC News debates during the 1968 election season, culminating in Buckley calling Vidal “queer” on air. Their shockingly large audience during the political conventions convinced other networks to turn to “debate” instead of reporting over subsequent election cycles, and the outgrowth of the shift was, yes, interest in having a Vidal/Buckley-style oil-and-vinegar pairing to review movies. Singer, a movie critic by trade, seems less fluent in the history of television. Much of the book’s research is similarly thin—primarily drawn from readily available newspaper and magazine articles, YouTube videos, and interviews with some of the people who worked with the critics that Singer seems to have done little to fact-check. Surely, we needn’t rely on anecdotes to estimate Siskel and Ebert’s salaries. Contracts must survive. As best I can tell, Singer either received no cooperation from PBS or Disney, or else made very little use of any surviving archival materials. Only a few press releases, concept art sketches, or production notes are mentioned, so most of the material in the book is anecdotal, of the “so-and-so says” variety. Perhaps it is symptomatic of the gradual switch to poorly preserved electronic communication that less material survives to document Siskel & Ebert than remains from the 1950s, the period I worked on for my forthcoming biography of James Dean. But if I could view Dean’s weekly pay stubs and even his phone bills from seventy years ago, surely something must survive to document two decades of a major TV show that was still on the air in living memory. I can see two versions of this book that could have worked brilliantly. Singer might have written it as a carefully modulated comedy, crafting an amusing and humorous story about two bickering mismatched antagonists who became accidental celebrities and learned to love each other. (As Singer notes, many at the time thought of Siskel & Ebert as a nonfiction sitcom--The Odd Couple, but incidentally about movies.) I would have approached it as a tragedy, tracing the rapid rise and long decline of Siskel & Ebert as symptomatic of the fracturing of the media landscape and the collapse of movies as a defining cultural force. Siskel and Ebert styled themselves as Roman emperors with their thumbs up/thumbs down voting, but they were late imperial rulers, presiding over the decline and fall of the movie industry’s cultural cachet. Writing the book this way requires a sense of tragedy—in the Greek sense, building toward catharsis—that doesn’t sit well with Singer’s love of Siskel and Ebert. So, we have a half-formed book that tries to be a comedy but can’t quite escape the tragedy, and somehow manages to make movies all but irrelevant to a book about movie critics. The anecdotes collected in Opposable Thumbs are often charming, humorous, and exasperating in equal measure, but with little structure to organize or contextualize them, the book becomes less than the sum of its parts. It’s fun to dip into and enjoy the nostalgia value, but I came away knowing little I did not know before and never feeling like I gained any real insight into Siskel, Ebert, or the movies. Gene Siskel once proposed a test for a movie’s value: “Is this film more interesting than a documentary of the same actors having lunch?” We might just as profitably ask whether a book is more interesting than having lunch with its subjects. Sadly, since neither Gene Siskel nor Roger Ebert is still alive to have lunch, Opposable Thumbs escapes an honest answer to that question.

6 Comments

Joe Scales

10/30/2023 09:52:30 am

I too preferred Ebert's point of view. Siskel's point of view was always, "I would have done this... or written that... or not done this, or that..." Then when he'd pick on Ebert, Ebert would get so defensive he'd spoil the movie.

Reply

Kent

10/30/2023 02:48:29 pm

Roger Ebert famously wrote a book on rice cookers. That's not an anti-asian slur it was about the actual kitchen appliance that one cooks rice in.

Reply

Philosopher obvious

10/31/2023 10:36:45 am

I had to look up Plato's Retreat and Sandstone. Joe Kent continues to be a bottomless source of sexual esoterica.

Reply

Joe Scales

11/2/2023 11:23:49 am

He's the one that hates jews, you imbecile.

Kent

11/4/2023 05:52:41 pm

You said "bottomless".

Pacal

11/10/2023 04:31:37 pm

I found Siskel and Ebert to be entertaining. However what we saw on TV was Film Criticism reduced to the simplest and lowest common denomenator. Nor particularily insightful or deep. The thumbs up and thunbs down approach sums it up quite nicely. Dedtailed truly interesting insight into film was simply not there. What we got was two guys in a bar talking about film in the most superficial manner. It was very entertaining but hardly serious in any real sense.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed