|

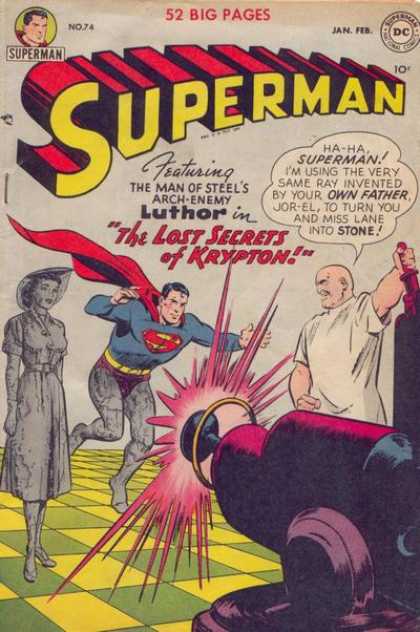

I could have planned this better. I should have started this review on Wednesday to do it in three parts. But since Ancient Aliens tonight plans an episode on “Aliens and Superheroes,” I will take advantage of what author Christopher Loring Knowles, following Jung, refers to as “meaningful coincidence” (synchronicity) to finish my review of Our Gods Wear Spandex today, despite the length of the resulting review. Chapter 5 This chapter is a very brief, very superficial overview of what Knowles describes as the nineteenth century, but which includes material ranging from Napoleonic Egyptomania to the renewed Egyptomania of the 1920s. He lists, in opinionated form, very brief highlights of imperialism, Egyptology, radical politics, and the rise of spiritualism. Then the chapter ends. Chapter 6 This chapter provides a brief overview of nineteenth century occult organizations and secret societies. The chapter could use some editing since Knowles states that it is about the rise of nineteenth century societies, but then devotes half its space to the Rosicrucians and the Freemasons, both of which predated the Victorians by quite some time. In discussing Freemasonry, Knowles says that “many” believe the organization is Templar in origin, and he devote half his discussion of the Masons to a potted history of the Templars. He concludes the chapter by asserting that Christian Science, Mormonism, and Transcendentalism all had “important links” to Freemasonry, and through it to Egyptian mystery religions. In the case of the Transcendentalists, the connection to Masonry is that Emerson gave a lecture at a Masonic Temple. His sources are again Graham Hancock and Robert Bavual, and also Michael Howard’s The Occult Conspiracy (1989), a fringe conspiracy book. Chapter 7 This chapter aims to cover the “Victorian occult explosion,” which he takes to begin with Bulwer-Lytton’s The Coming Race (1871), a claim that notably fails to understand either Victorian fantastic literature (growing out of the eighteenth century Gothic, itself steeped in the occult) and Victorian occult interests, developing out of spiritualism decades before Bulwer-Lytton. Knowles oddly refers to the novel as Vril, a title it attained only later, and it is evident that he has chosen to read the book as a monument of science fiction largely because first the Theosophists and then esoteric Nazism seized upon the mystical substance of vril from the novel, not due to its inherent popularity beyond occult believers. (Bovril, for example, takes its name from the novel.) Without stating a source or evidence, Knowles asserts that The Coming Race changed science fiction and led directly to the X-Men as the first example of a novel about a “super-race.” He writes that “it is difficult to overstate Bulwer's influence on his time. Using the conceit of science fiction, he pioneered the concept of a super-race whose powers far exceed those of ordinary men.” Bulwer’s book may have been the most popular, but there was an entire genre of earlier stories of fantastic and powerful races that lived underground or on remote islands, many derived from the nonfiction claims of John Cleves Symmes, Jr. and Jeremiah N. Reynolds on the civilizations within the hollow earth. So prevalent were these claims in the first half of the 1800s that Pres. John Quincy Adams signaled his support for an American expedition into the hollow earth before Andrew Jackson quashed the idea. The great lover Casanova wrote a five-volume novel about a fabulous underground race, while the pseudonymous Capt. Adam Seaborn’s 1820 novel Symzonia in which the hollow earth houses a utopian high-tech society. In short, Bulwer-Lytton was neither first nor unique. His book is remembered only because of Helena Blavatsky’s use of it, which is of course the lens through which Knowles views the era. Knowles takes the fictional Vril Society as fact based on a naïve reading of Morning of the Magicians, as summarized by later writers. He next gives a potted history of Theosophy, in which he describes Helena Blavatsky in glowing terms as “one of the first to bring Eastern mysticism to the West.” This neglects all the work of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century Orientalists, not to mention the Eastern synthesis of Schopenhauer. In the first half of the nineteenth century, there was a widespread belief that the East—particularly Hinduism—preserved the oldest traces of the pure Aryan religion, and therefore many in the era studied Eastern ideas. Blavatsky was a late entry, a gross popularizer of what academia had already processed and (largely) discarded. Knowles describes Blavatsky’s Isis Unveiled as her magnum opus, though that title more properly belongs to the longer and more intellectually sustained Secret Doctrine. I’m not sure he knows what magnum opus means. Knowles correctly understands the influence of Theosophy on popular culture, as well as Blavatsky’s indiscriminate use of fictional and nonfiction sources (she claimed science fiction writers were receiving channeled messages from beyond), but here the weakness of Knowles’s slipshod methodology is evident. He wants us to accept the idea that Secret Doctrine creates a precedent for “super-powered beings” in the form of the Ascended Masters, but he offers nothing to support this. What makes them super-powered? How are they similar to superheroes? He does not engage with the primary sources except once—all of his claims come from biographies of Blavatsky except for a single paraphrase of Blavatsky’s claims about Bulwer, which I suspect he actually got from a citation in one of the biographies. He doesn’t provide any examples or evidence from Blavatsky’s own work, nor does he address the darker side of Theosophy, including the racism encoded in its root races. The chapter concludes with a few paragraphs about the Golden Dawn that offer no information beyond a membership roster of fantasy writers. If this chapter was meant as an argument, it failed to make one. Chapter 8 At this point, my interest in the book has waned. There isn’t much by way of argument. In this chapter, Knowles provides potted sketches of Nietzsche, Aleister Crowley, Harry Houdini, and Edgar Cayce (!), and claims them all as precursors to the superheroes. No argument is made, least of all for why these men are connected to superheroes, and instead Knowles devotes space to speculating on the connection between Egyptologists Mark Lehner and Zahi Hawass and Edgar Cayce, suggesting a hidden occult agenda. Chapter 9 With this chapter we enter a new section of the book, devoted to pulp fiction—arguably a more important source for comics. He starts with Victorian pop culture and falsely claims that Spring-Heeled Jack was “the first detective character with a secret identity,” created in 1867. All of that is wrong; he was a folklore being, considered a monster, and had been appearing in person since 1837 and in literature (as a terror) since 1840. Following this, Knowles acknowledges but does not analyze “down market literature,” Poe, Doyle, Verne (whose science fiction he implies was derived from secret Freemason knowledge), Wells, and Stoker. He has no system to his choices, and he leaves out such essential figures for understanding the rise of the pulps as H. Rider Haggard, whose Allan Quartermain is arguably the template for much pulp adventure fiction. Chapter 10 Knowles attributes the rise of the pulps to Prohibition, claiming that they gave voice to “forbidden expression.” But this applies at best to a very narrow group of pulp magazines—not to the broader category, whose bestselling titles were Westerns, romances, and (of all things) railroad stories. Knowles myopically sees only adventure, detective, and shudder pulps as the hallmarks of the publishing category. He name checks Doc Savage and the Shadow among other pulp figures, and notes their direct inspiration on comic book figures, but attempts to limit their influence by claiming these figures as “dangerous” rather than wholesome, not fit to be “new gods.” He then gives an overview of science fiction and horror pulps, name checking Buck Rogers and H. P. Lovecraft, but making no argument about them other than to claim the government tried to destroy the pulps, pushing readers to comics. Chapter 11 In this chapter, Knowles profiles pulp authors and claims that they contributed to the future of comics by combining heroism with “ancient mysteries,” again failing to note H. Rider Haggard’s long shadow in this specific (and highly myopic) view of pulp adventure. He admits to being baffled as to why the Chinese were often cast as villains (the Yellow Peril escapes him) as he profiles Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, H. P. Lovecraft, and a few others. For his profile of Lovecraft, he relies on Kenneth Grant—the “magick” practitioner—to argue Lovecraft had extensive connections to the occult, and fringe writer Tracy Twyman to argue he was really writing about the Nephilim. His discussion of various authors focuses on their involvement in various occult groups, but he offers no examples of connections from primary sources, nor does he make an argument about the purpose (or lack thereof) of using occult themes. Chapter 12 Now we move into a new section, devoted to superheroes. He outlines the history of comics, but dismisses the Phantom as superhero antecedent (“essentially a circus-costumed version of Tarzan”). Chapter 13 This chapter posits that superheroes are savior figures and asserts that they are new forms of the “old gods” of mythology. However, since previous chapters failed to establish a direct continuity of paganism from Egypt to the pulps, it’s hard to agree with his conclusion that superheroes weren’t merely inspired by mythological heroes but are an occult manifestation of deity from the pre-Christian unconscious. He lists several comic magician-heroes and compares them to medieval magician figures like Merlin, as though their creators weren’t drawing on such imagery in making their wizards. Chapter 14 This chapter looks at figures like Captain Marvel and Superman as Jewish Messiah figures. He correctly notes the use of mythological allusions (particularly those inspired by Theosophy or The Golden Bough) in many superhero comics, but he also occasionally overreaches, especially in implying, without evidence, that such characters as Hawk-Man were not modeled on ancient myths for entertainment purposes but somehow were designed to embody these myths as part of a hidden occult revival. Knowles never explicitly says but seems to want us to believe that an ineffable zeitgeist based on occult influences dictates which heroes become popular based on how they embody ancient gods. Chapter 15 This chapter briefly reviews the Silver Age but barely makes an argument except for the commonplace observation, presented as revelation, that the heroes of the time reflected cultural fascination with Big Science and the military-industrial complex. Much of the material is drawn directly from Comic Book Nation (2001) by Bradford W. Wright, a much better book, which I have read and actually have on my bookshelf next to me as I write this. Chapter 16 I’ll be damned if I follow this chapter. Knowles discusses the golem, the monstrous mud creature of Jewish folklore (though he wrongly claims the creature was first described in 1847 instead of in the Talmud), and tells us that Batman is a golem because he, too, is a protective avenger fueled by rage. He then drops the claim and talks about the psychedelic Bat-adventures of the 1950s and ties it to the 1960s goofiest fantasy sitcoms like I Dream of Jeanie. “During the Sixties, monsters and myths resurfaced as a part of the popular mind, and an unprecedented Dionysian explosion capped off the decade.” He neglects the role of “Monster Culture”—the revival of Universal Horror—in those years, arguably a bigger influence on pop culture than Batman’s encounter with Bat Ape. So broad is Knowles’s view of the golem that he can lump in the Hulk and Daredevil alongside Dirty Harry. It would take a full article just to deconstruct this chapter, but since Knowles engages neither in close textual criticism nor in historical investigation into the influences and origins of any of these characters, his claim is simply an assertion, provided without support. Chapter 17 This chapter likens female superheroes to the Greek mythic Amazons and warrior goddesses like Athena. Wonder Woman is explicitly modeled on such myths, so this is not a revelation. The chapter lists female heroines’ greatest hits, but makes no broader argument. Chapter 18 In this chapter Knowles suggests that teams of superheroes like the Justice League reflect “the Brotherhood archetype” rather than a marketing gimmick. He does not defend this assertion, taking it as a given that we believe that archetypes spontaneously influence human history. He merely lists various superhero groups and their history. Chapter 19 Knowles makes the interesting observation that mad scientist figures are substitutes for wizards in earlier myths, and he suggests that Lex Luthor was modeled on Alesiter Crowley. But he can’t help but overreach: He claims that a checkerboard floor on the cover of Superman #74 represents a Masonic Lodge (?!) and that Lex Luthor’s ray gun on that cover is a secret phallus to represent Crowley’s bisexuality. Chapter 20 Your enjoyment of this chapter’s potted biographies of comics creators depends on how much you agree with its thesis: Given the magical history of superheroes and comic books, it's no accident that some of the most influential comics creators have had a strong interest in mythology and the occult. In fact, there is a definite evolution at work in the process by which the comics incorporated the occult. It starts with a naïve fascination (Jerry Siegel), gives way to intentional mythologizing (Jack Kirby), develops into a systematic understanding (Alan Moore), and finally evolves into a new kind of religion best exemplified by Alex Ross. After profiling many comics creators, Knowles concludes that Ross’s Kingdom Come series is the most important for understanding the transformation of superheroes into almost literal gods. It is unclear, though, that he is differentiating between their function within comics and how fans (or the general public) treat them outside of the stories. Here is the key sentence: “If Ross did not set out intentionally to reintroduce the ancient gods and goddesses to a modern audience, then we must seriously contemplate whether some other supernatural force was working through him to do so.” One could (as I have in the past) equally argue that horror monsters like vampires have taken on the qualities of pagan deities and, within modern horror stories (and especially their Gothic romance cousins), function akin to pagan gods. This would seem to undermine the unique qualities Knowles wishes to ascribe to superheroes and instead imply that old stories, plots, and characters are continuously recycled. I guess it’s possible to suggest that pagan gods are plotting their resurrection “not in the spaces we know, but between them,” but Knowles wants to see a secret stream of paganism that operates independently of individuals, a sort of living Akashic Record in what he calls our “collective consciousness.” We really need much more evidence to even begin to entertain this. Chapter 21 This chapter meditates on why comics are popular and says nothing original; in fact, it may even make the reader a little less informed by taking Alan Moore literally in asserting that “The gods of magic in the ancient cultures … are also the gods of writing.” Knowles want us to read this as an invocation of the power of magic and divinity, while Moore meant it as a paean to the power of storytelling. Chapter 22 The conclusion makes many observations and assertions that require evidence to support, evidence the preceding chapters failed to provide. He claims that the decline of religion sent audiences to comics and to Star Wars for “salvation” from modern problems—apparently missing the religious revival of evangelicalism. He asserts that comics’ superpowers, as depicted in movies, will make the young demand superpowers of their own in a technologically-derived “totally new human reality.” Thus, he says, Kingdom Come provides a moral compass to follow in navigating “transhumanism.” He hopes technology will let us understand occult science better, and thus to see new relevance in ancient myths. Overall, the book was superficial, poorly-researched, and overly broad in its claims. Knowles asserted many things, supported almost none of them, and talked around his actual theme, one that was heavily implied but unstated: that there is some supernatural force that continuously resurrects pagan pantheons and acts through artists. You’ll recognize the claim, of course. It comes directly from Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine: Our best modern novelists, who are neither Theosophists nor Spiritualists, begin to have, nevertheless, very psychological and suggestively Occult dreams […] [T]he clever novelist seems to repeat the history of all the now degraded and down-fallen races of humanity. Our Gods Wear Spandex failed to prove its case because it didn’t really have one. There were many ways to approach such a topic. The most obvious would be to chronicle the use of mythological themes in comics with a deep reading and analysis of primary source texts, to interview surviving artists about their influences, and to compare superhero uses of these tropes to the appearance of myth in other genres (horror and sci-fi come to mind). Knowles’s approach was a non-approach, a series of disconnected chapters that vaguely talked around some broader themes, drawn largely from secondary sources, and without any attempt at methodology. Past and present are mixed together as though stories never developed but simply emerged fully formed from some Jungian repository of archetypes. It was, in short, a mess.

32 Comments

Greg Little

8/22/2014 04:07:54 am

Jung didn't term it "meaningful synchronicity." Synchronicity is a meaningful coincidence. Two (at least) events occur in time and space that appear to be unconnected by causality, but they are connected by meaning.

Reply

8/22/2014 04:10:19 am

My fault. I meant to write "meaningful coincidence." I'll fix it.

Reply

Greg Little

8/22/2014 04:11:28 am

Kudos!

spookyparadigm

8/22/2014 06:18:37 am

Wait.

Reply

8/22/2014 06:27:21 am

I'd give you the last point if he didn't spend so much time defining the pulps by the type of paper used to print them. You're absolutely right that most will think of adventure, but it was really up to him to acknowledge his definitions and his choice of focus.

Reply

spookyparadigm

8/22/2014 06:34:14 am

I suspected as much, but I just wanted a platform to note my tired-ness of poor understandings of pulp AND the contradictory impulse against people who are hyper-literal in their definitions. :)

Clint Knapp

8/22/2014 06:29:02 am

Glad I'm not the only one completely baffled by such rigorous leaning on Kingdom Come. It's a great book, and Ross's art is legendary, but Jesus... that was 1996. Hardly anywhere close to anything even remotely resembling the origin of mythological connection in comics.

Reply

EP

8/22/2014 06:56:42 am

"Hardly anywhere close to anything even remotely resembling the origin of mythological connection in comics."

Clint Knapp

8/22/2014 06:21:08 am

Stop! Hold the phone. Didn't he just spend all that time arguing the occult importance of the super-race that lead to the X-Men? Then how can he complain the Silver Age was all about Big Science? The X-Men were one of the most influential creations of the Silver Age!

Reply

8/22/2014 06:31:56 am

Knowles lists the X-Men as one of the "Brotherhood" groups, which he sees as separate from the Silver Age individual heroes. The latter are "science" heroes, though some are golems, and... well, I guess he has a classification scheme. He also says the X-Men are an "unconscious expression of Lee's deep-seated feelings of Jewish persecution." I guess Lee either agreed or never read the book since he wrote a blurb for the back cover.

Reply

Clint Knapp

8/22/2014 06:42:31 am

Oh, I'm sure there was some degree of Lee's feelings toward anti-Semitism; that's why Magneto's powers are the reason he is a concentration camp survivor.

spookyparadigm

8/22/2014 06:38:49 am

To be fair, much of the industry decided to see their future through Moore's infamous "bad mood" as he put it. So I can't really blame some of them taking the opposite tack and following his mystical impulses.

Reply

8/22/2014 06:46:13 am

He's given one page (in my epub edition) that summarizes his career with almost no analysis. He notes Morrison's claim to be in contact with space aliens and calls his work "pure prestidigitation."

spookyparadigm

8/22/2014 06:47:35 am

If that's all a book on comics and occultism has to say about The Invisibles, yeah, ok.

spookyparadigm

8/22/2014 06:51:16 am

Let me amend that. One could make a point, as Clint does above for Kingdom Come, that if one is tracing a secret history, that's way too recent for the historical. Fair enough.

EP

8/22/2014 06:53:04 am

"Yeah, ok" should be the subtitle of any future hypothetical biographical study of Knowles.

EP

8/22/2014 06:54:24 am

Jay-Z is Nyaralhotep. Everyone knows that. 8/22/2014 06:55:40 am

Here's the whole of his discussion of "The Invisibles":

Clint Knapp

8/22/2014 07:44:07 am

That's a shame. The Invisibles, was a good book, and a more lucid revelation of the weird side of the fringe and how they work than anything I've seen out of Knowles yet.

EP

8/22/2014 06:49:53 am

"Verne (whose science fiction he implies was derived from secret Freemason knowledge)"

Reply

Kal

8/22/2014 07:21:47 am

What an no Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles or Transformers, or Voltron or Space Battleship Yamato (StarBlazers), or Macross (Robotech), in this book? All of them had comics and TV shows in the 70s and 80s and all were not just cult hits. They had superheres and villains, even a monster planet, and dimension hopping alien bad guys.

Reply

EP

8/22/2014 07:26:01 am

I want a book on the Zoroastrian themes in Thundercats! Christopher Knowles, get on it!

Reply

spookyparadigm

8/22/2014 07:34:16 am

You clearly haven't googled

EP

8/22/2014 07:52:42 am

Why do you keep trying to hurt me, man? :)

Only Me

8/22/2014 11:20:27 am

@spookyparadigm

Shane Sullivan

8/22/2014 07:43:06 am

“If Ross did not set out intentionally to reintroduce the ancient gods and goddesses to a modern audience, then we must seriously contemplate whether some other supernatural force was working through him to do so.”

Reply

Lucas

8/22/2014 07:43:58 am

William Whiston has Hollow Earth ideas. He is before Verne.

Reply

EP

8/22/2014 07:55:31 am

Given that the Greeks believed in the periodicity of *everything* celestial, they are to be expected to have assumed periodicity of comets on general principle.

Reply

me

8/22/2014 11:42:57 am

Christ if returning HAS to wear spandex...too?

Reply

EP

8/22/2014 11:49:11 am

Either . or Only Me trolling me. (I mean myself, not himself.)

Reply

Duke of URL

8/24/2014 06:26:43 am

<sarc>Thank you SO much.</sarc>

Reply

EP

8/23/2014 06:03:44 am

"nor does he address the darker side of Theosophy, including the racism encoded in its root races."

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed