|

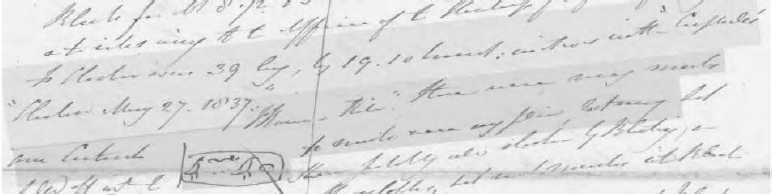

Yesterday I presented the first half of my review of Scott Creighton’s new book The Great Pyramid Hoax (Bear & Company, 2017), a book that takes a chapter from his previous 2015 book The Secret Chamber of Osiris and expands it to ten times its original size. Stripped of context and purpose, this inflated chapter becomes mostly unreadable as a book, an incomplete indictment of the “quarry marks” in the relieving chambers of the Great Pyramid that Creighton never bothers to give much in terms of purpose. Aside from a few vague assurances that discrediting these marks would leave the Great Pyramid’s builder uncertain, he never uses that assertion to build a case for anything, nor does he suggest, as he did in his previous book, that the Pyramid is anything but an Old Kingdom construction. If one were not already a reader of Scott Creighton’s books, I imagine this now volume would seem dry and pointless. As we move in to the back two-thirds of the book, Creighton attempts to marshal evidence to support the tentative hypothesis that he proposed in the first section of the book. It remains unconvincing. One chapter argues that the three red splotches photographed by Rudolph Gantenbrink’s robot at the top of one of the Queen’s Chamber “air” shafts in 1993 are orthographically dissimilar to the quarry marks in the Kings’ Chamber relieving chamber, thus indicating that the relieving chamber marks were made later. There are too many problems to count here: (a) The marks in the air shaft have only tentatively been identified and are not certain, so orthography can’t be determined. (b) Since we don’t know what the characters were, we can’t conclude that the project “required” the same writing style on every stone for “efficiency.” Etc. etc. Next, Creighton attempts to show that Vyse was lying about having discovered quarry marks showing Khufu’s name. His argument is again circumstantial: Vyse’s journal of March 30, 1837 records his initial impressions: “In Wellington’s chamber, there are marks in the area of the stones like quarry marks of red paint, also the figure of a bird near them, but nothing like hieroglyphics.” Creighton takes this to mean that the cartouches were not present, not that Vyse reconsidered his opinion after more careful viewing and analysis. Following this, he introduces into evidence a confusing bit of hearsay. After Zecharia Sitchin accused Vyse of forgery, a man named Walter M. Allen of Pittsburgh claimed in 1983 that his elderly relatives had told him that his great-grandfather, Humphries Brewer, was one of Vyse’s companions and believed that some of the “faint” quarry marks had been repainted and “some were new.” This testimony is suspect since it is both third-hand (Allen’s account of elderly people’s memories of something someone might once have said decades after the fact about an event from more than a century earlier) and conveniently timed after Sitchin created a controversy. While Allen made his claims verbally in 1983, a written version was not published until Sitchin himself did so in 2007, after Allen was conveniently dead. At that time, Sitchin presented a log book recording Allen’s conversations with his elderly relatives. Allen claimed that these notes were written in 1954, which even if true would not make the claims within them true, if for no other reason than for the same reasons Creighton attributes to Vyse: potential motivation to support some preexisting idea at odds with the facts. Indeed, the suggestion that the marks were too faint to clearly see actually argues against Creighton’s claim that Vyse could not possibly have overlooked the marks on his first survey of the relieving chambers. Brewer’s name does not appear in Vyse’s records, and Creighton explains that this is because Vyse tried to expunge any record of him to hide the forgery. At the same time, he says that he might have found Brewer’s name in photographs of Vyse’s notebooks, but he said that it was impossible to tell because of Vyse’s bad handwriting. He declined to cite the page or provide a copy of the relevant words to let readers judge for themselves, despite having provided the same evidence for other excerpts of the journals. He says only that the name appears in the “relevant” section of the 600+ page journal. One might ask why he declined to share proof, but I fear the answer is probably clear. Creighton devotes enormous space to trying to prove that Allen’s notes are not a forgery—but a forgery of what? They are secondhand recollections of what someone supposedly had read in now-lost papers ages ago. Even so, Creighton argues that the notes must be correct because they contain details a forger would not have readily known: the existence of Prussia (really?), the geographical extent of the Austrian Empire (has he seen a map?), and the fact that a certain Mr. Raven was part of the discussion of the quarry marks. Not to put too fine a point on it, but if the text were a forgery, it could have been forged from entries for May 1837 in Vyse’s book Operations Carried on at the Great Pyramid, where Vyse states that Raven was left alone at the pyramid while he was away, between the time of the discovery of the quarry marks in one chamber (entry for May 9) and when Vyse’s team signed a statement attesting to the accuracy of the copies made from them (entry for May 19). Thus a forger might have thought to finger him as fabricating some of them, even if the chronology doesn’t work out perfectly for the uppermost chamber. This isn’t to say the text is a forgery, only that Creighton’s argument for their authenticity doesn’t follow absolutely from the written evidence. If the text is not a forgery, it still only proves that Brewer suspected Raven of manipulating the quarry marks while Vyse was away. His next piece of evidence is the fact that one of Vyse’s assistants, the man who drew copies of the marks, signed two of twenty-four drawings on the wrong side, thus “proving” that they were made before the quarry marks were painted onto the wall in a different and/or incorrect direction. He claims that an analysis of photographs of the paint suggest that the signs were written left-to-right and while the blocks were upright, in contravention of Egyptological consensus, a consensus he doesn’t seem to be able to cite or discuss with sources outside other fringe books’ summaries. Creighton, who likes to cite the Graham Hancock website forum, discussed these claims on the board in 2014 and received extensive criticism from Martin Stower, which made no impression on him. Weirdly, the book then returns to repeat the same material from earlier about Vyse’s journal—because he is lightly rewriting a chapter from his last book, mostly point for point—and Creighton makes it sound like it was the result of careful sleuthing that he found the document. It shouldn’t have taken much effort. It’s held in a museum and listed online in its holdings. It’s not hiding. In the journal, Creighton finds that Vyse made several attempts at copying the cartouches of Khufu, each time getting some of the details wrong until he finally made a correct copy. Creighton instead reads this as progressive efforts to draft a fake cartouche to forge, with the final details—specifically three horizontal lines in the circle within the cartouche—hastily added at the end to “fix” the spelling of Khufu due to late-breaking discoveries elsewhere at Giza that month. Creighton, recapping his last book without mentioning the fact, says that the following lines from the journal prove that Vyse ordered his henchman to fabricate Khufu’s cartouche, and he claims it as a new discovery despite having published the same text in his 2015 book: The chamber was 39 long, by 19.10 broad: as it was within “Campbell’s Chamber May 27, 1837.” “For Raven & Hill.” These were my marks from cartouche to inscribe over any plain, low trussing. This doesn’t make much sense as written, and for good reason. In 2015, Creighton wasn’t sure of many word readings and scattered question marks throughout his transcript. They’re all gone now even though the text isn’t any clearer. (He concedes the point a few pages later.)

I’m not confident in many of his readings because the provided photo isn’t sharp enough to confirm them. The words “For Raven & Hill” more closely seem to read “H Raven & Hill,” which are the words actually painted in the chamber. The words “low trussing” do not seems to appear in the photograph he provided, though I cannot read the squiggle in their place. (Vyse did not use the word “trussing” in his published work.) For that matter, the word Creighton reads as “inscribe” seems to have a loop at the start rather than Vyse’s distinctive dotted “i.” Regardless, though, the meaning seems to be that Vyse was recording a dedication of “H Raven & Hill” painted in the chamber along with the existing cartouche that he had copied into his notes. Creighton reads this instead as orders to forge a cartouche, too. Because he does not transcribe the surrounding lines, Creighton left out too much of the context to support his reading of the line he claims to be a smoking gun. Frankly, even if we accepted all of Creighton’s evidence at face value, it would mostly suggest that Vyse’s team tried to make some markings easier to read by repainting them and Brewer thought they did so bad a job that it essentially made them into new figures. I don’t think this is what happened, but there are many interpretations of the evidence short of intentional forgery that Creighton failed to consider. The final chapter simply repeats all the previous chapters’ arguments, which themselves had already been restated in summaries at the end of each chapter. These, in turn, were recycling material from The Secret Chamber of Osiris. A lot of this book is repetition and recycling. Worse, there are consistency errors as the author brings up points for later discussion that vanish, and repeats earlier points as though presenting them for the first time. Overall, the book is downright uninteresting. It has nothing new to say to readers of his earlier book. It is obsessed with minutiae to the exclusion of context, arguing for a forgery without establishing a compelling motive and by making assumptions about “secret” texts that Vyse must first have found and somehow chose not to report, even though such a discovery would itself have been cause for celebration. (Not to mention confirmation of the inscriptions in the Pyramid.) Creighton’s argument asks us to share his own ignorance about the political, social, cultural, and archaeological contexts in which Vyse operated, and it expects readers to come to the book already accepting the notion that there is no other reason to believe the pyramids to be of dynastic Egyptian origin except for the quarry marks found within them.

21 Comments

Martin Stower

9/23/2016 12:53:35 pm

I find it encouraging that you’ve spotted what the “Raven & Hill” reference really is. I take it that others will do likewise, or at least spot the quotation marks, which are surely obvious even in a poor quality image of Vyse’s near impenetrable handwriting. Funny how they escaped his various listed helpers, “handwriting experts” included.

Reply

Only Me

9/23/2016 01:48:38 pm

Relevant photo from the discussion. Fellow readers, look for H Raven & Hill above Martin.

Reply

Only Me

9/23/2016 01:36:37 pm

After this, I can safely say Creighton is in the bantamweight division of fringe authorship.

Reply

Jean Stone

9/23/2016 02:53:06 pm

This whole thing puts me in mind of the original Stargate movie with Daniel presenting his arguments for, essentially, ancient aliens, including criticizing Vyse and I remember the novelisation actually expanded that argument. Wonder which fringe source they got it from. I also wonder if any people were inspired into fringe-y beliefs from that film. Not that it was new in its use of those elements, but what is in this field anyways?

Reply

Martin Stower

9/23/2016 09:17:43 pm

Year of the original was 1994, which suggests that they got it direct from Sitchin, as not so many had repeated the claim by then.

Reply

David Bradbury

9/23/2016 03:01:21 pm

Any readers live near Aylesbury?

Reply

Martin Stower

9/23/2016 08:05:00 pm

That’s the one. I examined it in 1998. Could do with a return visit.

Reply

Martin Stower

9/23/2016 03:16:08 pm

Concerning Creighton’s suggesting that the name “Brewer” appears in the manuscript journal, when he presented the relevant image (now missing) on GHMB, it was cropped to such an extent that the word was barely shown adequately and all and any context which might help us determine if it is a name was excluded. Vyse would typically write “Mr. Brewer” and the names of those who took part in the operations (as Brewer allegedly did)—Hill, Raven, Perring, Brettell—appear many times and not just once.

Reply

Only Me

9/23/2016 07:29:53 pm

One of the participants on the post you linked to included this gem:

Reply

Martin Stower

9/23/2016 08:16:34 pm

“These were my marks from cartouche to inscribe over any plain, low trussing.” Such a natural thing to say! About as convincing as the messages people hear when they listen to records played backwards.

Reply

Martin Stower

9/24/2016 03:39:54 pm

Considering this again, I gather that since he gave this an outing in his last book, he’s spotted the quotation marks—which makes it all the more odd that he fails even now to understand the implications of their presence.

Reply

Martin stower

9/25/2016 10:10:47 am

“. . . Creighton argues that the notes must be correct because they contain details a forger would not have readily known . . .”

Reply

Peter Robertson

9/26/2016 05:56:46 am

Mr Colavito, you finish your 'review' with the following comment:

Reply

Martin Stower

9/26/2016 12:41:40 pm

Not sure why you’ve included the URL of this page. Were you planning to post this elsewhere?

Reply

Peter Robertson

9/26/2016 12:59:30 pm

Thank you Mr Stower. But my question was directed towards Jason and I am sure he is more than able to speak for himself.

Martin Stower

9/26/2016 01:29:45 pm

For Peter Robinson:

Reply

Martin Stower

9/26/2016 02:00:13 pm

Robertson, Robinson . . .

Reply

Peter Robertson

9/27/2016 06:33:54 am

Mr Colavito,

Reply

Peter Robertson

9/27/2016 06:44:10 am

If he now has an entire book on the subject with even more evidence to present then I, for one, will most certainly be taking a look at it. And I say that because, in the first place, I tend not to form my reading list on the opinions of others and especially not when those opinions are at a complete variance from my own experience.

Reply

Martin Stower

9/27/2016 10:04:27 am

Wow, Mr Robertson, you seem pretty zealous (in Scott Creighton’s cause) yourself.

Reply

Chris Aitken

10/2/2016 08:39:35 am

I'm just going off the cuff here, as I'm no expert. But it always amazes me how people can't seem to except that people simply evolved. In the case of The Great Pyramid it seems obvious that a) It was built by and ascribed to the correct individual. b) This structure is really the apex of pyramid development in ancient Egypt. There's plenty of evidence of previous failed attempts. Also, since this practice reached a pinnacle at this juncture...there's really nothing as great afterwards...there was one smaller black pyramid built afterwards, but the romans stripped it...thereafter burials moved to the valley of the kings. Basically, pyramids became too ridiculous and expensive, and despite the clever traps became beacons for bandits.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed