|

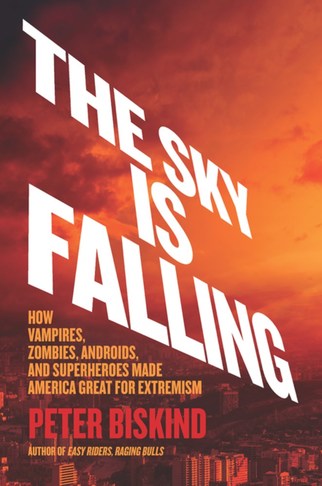

The Sky Is Falling: How Vampires, Zombies, Androids, and Superheroes Made America Great for Extremism Peter Biskind | 256 pages | New Press | Sept. 11, 2018 | ISBN 9781620974292 | $26.99 During the 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, commissioned a study to better target the kinds of voters Trump would need to reach to win the election. According to an interview Kushner later gave to Forbes magazine, he learned that Trump voters were most likely to be fans of AMC’s zombie drama The Walking Dead, a show about rugged individualists struggling to beat back hordes of rampaging zombies that constantly breach their border walls after the total collapse of the federal government. Consequently, the Trump team bought air time during the broadcast. It was neither the first nor the last time that The Walking Dead—a rural-themed show with the formal structure of midcentury cowboys-and-Indians movie—has been viewed as a conservative drama. As I wrote in my Knowing Fear a decade ago, horror is almost by definition structurally conservative since it revolves around breaches of the status quo.  But this incident helped to inspire cultural critic and journalist Peter Biskind to look into the question of whether genre movies and TV shows helped to pave the way for what he calls an era of unprecedented political extremism in the United States by denigrating unifying institutions and celebrating ideologies formerly associated with the fringe of American life. His analysis is simplistic, and I believe he is wrong to imagine that art creates culture. Instead, the balance is more precarious, with art and culture feeding one another. The Walking Dead did not open America to Trump but it did reflect the cultural forces that he exploited. Biskind opens The Sky Is Falling with a superficial, if not entirely incorrect, examination of the politics of the past seventy years—a period that starts long enough in the past that it forms a sort of mythical golden age but one that is close enough that the children of the 1950s are still around to wax nostalgic about their childhoods. Biskind imagines that the 1950s were a tranquil period when extremism had been cast out of American life, and he skips over the turbulent 1960s and 1970s—a time of violence and extremism—to paint a picture of contemporary partisanship as the most painful outbreak of internal hostility since the end of World War II. He remembers that extremists existed even in the 1950s, but he misdiagnoses the reason for their exile from power. It is not that their ideas held no truck; it was that the centrists in both parties had temporarily come together to foster stability against a bigger threat than political differences: The Soviet Union. As that threat receded, internal divisions reemerged. Biskind never quite defines what he means by “extremism,” with his definition floating at times between communism and fascism on one hand and the “extremism” of Hillary Clinton and George W. Bush on the other. Sometimes “extremism” is for him revolutionary, and other times it is any belief that prioritizes individual action over collective government responses. The biggest problem in Biskind’s analysis—and all of those that follow from a nostalgia for the 1950s and 1960s—is that the postwar period of consensus lasted only about twenty years. That’s twenty years out of America’s more than 250. That’s twenty years set against the fifty years since it ended. It is nostalgia for a blip, an anomaly, a brief moment when the devastation of war left America in a position that simply could not be sustained. To imagine it as not just ideal but normal is to mistake one’s childhood for the Golden Age. Biskind is 78. His adolescence and young adult years just happen to coincide with this period of presumed glory. I would also be remiss if I did not mention that Biskind limits his analysis primarily to science fiction, horror, and “adventure” films (meaning action movies, otherwise not paranormal), all of which are targeted to a young male audience. Were he to devote the same effort to female-coded genres such as romance, for example, or even to comedy, I am sure that he would arrive at a different set of conclusions. Part of the apocalyptic tone he decries is simply part and parcel of the genre. It is perhaps telling that the notes to the book scrupulously cite current events to news articles but contain virtually no references to popular or scholarly critical analysis of film or television, or any works of media, film, or cultural theory. Biskind believes, like many cranky old grandfathers, that television shows and movies can be classified into liberal, centrist, and conservative narratives and that they are sending secret political messages to indoctrinate audiences into extremism. For him, science fiction can be broken down into these three themes, of which liberal and conservative are the most prominent. When aliens are benevolent, it’s a liberal movie. When they attack, it’s a conservative one. When the narrative focuses on science, it’s liberal. When it focuses on law enforcement or the military, it’s conservative. I think that Biskind oversimplifies and projects political clichés onto cinematic clichés. In his introduction, he unintentionally reveals the truth—what he sees as politically liberal or conservative is really a question of tolerance. When a movie or TV show sympathizes with characters who aren’t straight white men, he brands it as liberal. When it expresses fear of characters who aren’t straight white men, he claims it for conservatism. The “politics” he sees is really a question of how we perceive the “Other.” In the 1950s and 1960s, the “Other” had a racial and a national dimension, and often a sexual and gendered one, but today we have added political affiliation to the characteristics that count as “Other.” If these themes map to current liberal/conservative divides, it is because of the polarization we now experience in regard to the categories of straight, white, and male taking on added political weight through conservatives claiming them as synecdoche for their worldview. Biskind’s analysis of the deep themes of horror is similarly blinkered. Preferring politics to the underlying social and epistemological facets of the monster—the subject of so much academic work—he says, bluntly, “In the same way that savages are just savages in mainstream shows, so too are monsters just monsters.” The only exception is when they are political. That’s just not right. It so happens that I was once an expert in this field and carefully researched this subject. As I discuss in my book Knowing Fear, there are both culturally liberal and conservative themes in speculative fiction film and literature, but these rarely map neatly onto the faux-liberalism and faux-conservatism passing under the brands of the Democratic and Republican parties, whose inconsistent positions, born of expediency and cash payments, are only approximately aligned to traditional ideological divisions. I should hope that conservatism isn’t so morally bankrupt that, as Biskind asserts, its adherents actively root against doctors because they want to see the military blow up any perceived threat, or that liberalism isn’t so threadbare as to root against police and soldiers as automatic agents of evil. He rails against “leftist” science fiction movies of the past thirty years for convincing audiences that corporations are oppressive and capitalism is evil, as though the early science fiction classic Metropolis didn’t feature workers rising up against evil and corrupt industrialists in 1927. For Biskind, however, the demonization of American economic and political institutions, or the depiction of their incompetence and failure, is a symptom of Modern Times. Biskind forgets that the idea of subversive narratives or stories where American institutions fail are not unique to our era. Alfred Hitchcock used to showcase them every week on his Alfred Hitchcock Presents. What differed in the past is that the CBS network used to make Hitchcock deliver a milquetoast spoken epilogue facetiously claiming that the subversive ending the viewer just saw was undone by a stroke of fate, restoring order. But CBS (and later NBC) didn’t do that because of a commitment to centrism but because of expediency—TV was regulated heavily then, and heavily dependent on sponsors who needed mass audiences not to be offended, so keeping on the government’s and corporations’ good sides meant upholding “decency” and the most inoffensive of common values. Where commercial needs were less important—like in pulp fiction novels and magazines—a very different story emerges. Try reading some midcentury pulp fiction sometime, or even the collection of stories Hitchcock put out that CBS would not allow him to film for TV. Modern narratives aren’t an expression of a new extremism as much as they are the kinds of stories that would always have been told on TV and not just in magazines and paperback novels if the regulatory state hadn’t used its control of the airwaves to minimize them. Claiming particular government policies, born of political expediency and corporate profit-mongering, are an expression of what is essentially the General Will rubs me the wrong way. But there is a core that remains to Biskind’s argument. He is right that entertainment reflects culture and helps to shape audience attitudes. He is also right that modern entertainment seems to give a more prominent place to apocalyptic scenarios, post-apocalyptic survival narratives, and stories that represent a lack of faith in either government or humanity. But I don’t think that it is reducible to a facile formula born of a particular partisan divide that has had its current form only since the late 1990s. America has always had an apocalyptic streak—look at the regular occurrence of end of the world cults—and it has always hosted arguments between those who want to expand the social contract to greater numbers and those who would restrict it to fewer people. The darkness in modern genre fiction reflects, yes, a lack of hope and concern about the future. But it is also the ruthless result of corporate forces that pick particular narratives because they sell well, generate buzz, and produce sufficient spectacle to keep audiences coming back. The end of the world is the natural end point of the blockbuster mentality. The stakes kept going up from that first shark attack in Jaws, and now only the end of existence can satisfy jaded audiences that expect ever greater stakes to titillate them. Beyond the overbearing effort to render all entertainment partisan, Biskind’s writing style tends to undermine his case. Biskind has been writing about pop culture for a long time, so surely he realizes that his own prose is studded with clichés and the tired detritus of last year’s conventional wisdom. Why else use the trite descriptor “interchangeable Chrises” to describe Evans, Pratt, Hemsworth, and Pine, except that it was a cliché in movie reviews a year or two ago? Why else refer to the supernatural as “the supe world” except that some teenager on Snap Chat did? Why use “POTUS” in place of “president” except to sound au courant with Washington-speak? He lards his prose with adjectives to make quite clear to the reader which movies and TV shows he loves, and which he doesn’t. But his desire to show off his superior taste undercuts his analysis by making it seem that works he favors are by definition healthier and more acceptable than those he dislikes for aesthetic reasons. His chapters, roughly thematic but overlapping in content a bit too much, tend to break down into plot summaries strung together by thin, impressionistic arguments based on the author’s tastes. He claims, for example, that science fiction films no longer engage in the awe and wonder of exploration, but he doesn’t back that up. Yes, Alien was a scary film that saw space as horror, but plenty of 1950s films found terrible frights in space, too. To make the argument work, Biskind needed data to quantify whether themes and plots have really changed, and how much. I get the feeling that one could cherry-pick a different set of films and TV shows and produce exactly the opposite conclusions from those Biskind offers. A dull chapter on the Left Behind series seems out of place since Biskind’s book is not about books, and the halfhearted movie versions had almost no traction outside of evangelical circles, which hardly needed the films to become right-leaning. Overall, Biskind is too rigorous in his effort to politicize films and TV shows, particularly since he chooses not to use any sort of quantitative data to justify his subjective readings, which tend to revolve around only a handful of properties: Lost, The Walking Dead, Game of Thrones, and inexplicably True Blood foremost among them. It’s true that movies and TV series reflect the culture in which they are created. But they are also art, which means that they have more than one potential reading and a certain degree of ambiguity that allows for their narratives to be applied and reapplied in new and different ways. At one point, Biskind seems amazed that The Hunger Games could be read as both right- and left-leaning. Biskind expresses his own discomfort at the fact that Black Panther (2018) “seems initially to come from the left” because of its diversity but its lead characters is “more like Donald Trump” because of his African version of American exceptionalism. The latter half of that sentence was a popular alt-right meme earlier this year, and Biskind simply can’t hold it in his head that art can contain different meanings and possible interpretations. Despite this, The Sky Is Falling has some provocative ideas and offers an interesting, if flawed, argument for popular entertainment as reflection and driver of political discourse. If you can set aside the stylistic tics and the more strident efforts to slot every media product as part of the current liberal/conservative divide, there are elements of the book worth reading and arguments worth hearing. Ultimately, Biskind raises a difficult question: To what extent do the stories that we tell ourselves drive us to live up to the values those stories depict? And does that mean that the people who tell those stories have a moral obligation to consider the consequences of the themes they explore? When Rod Serling wrote a drama about a bomb on board an airplane, he was horrified to discover that someone watching the show on TV used it as a template for calling in a bomb threat, one of the first such threats against an airplane. He was so shaken that he vowed never to write another drama outlining an original crime that some future criminal might imitate. It is worth considering whether Hollywood should consider the degree to which the stories they present might drive audiences in unwelcome directions, and what they should do about it.

32 Comments

Pops

8/9/2018 11:08:50 am

Very interesting post. It’s true that art and entertainment have many interpretations that don’t hold true for everyone. Biskind’s book has some flaws but I also agree that the core principle of his work has something to say. Biskind is over 70 years old so I bet he holds nostalgia that his time was the best or reasonable so it would be a good thing to keep that in mind while reading his book. I believe the biggest flaw is that Biskind ignores the complexity of art, culture, media, entertainment, and politics so he can weave a simplistic narrative. Other than that, his book does have some thought provoking analysis.

Reply

Machala

8/9/2018 12:48:22 pm

I'm slightly younger than Biskind, but age must have fogged his memory of the 50's, because it certainly doesn't jibe with my recollections.

Reply

Machala

8/9/2018 12:52:41 pm

Speaking of Conservatives....

Aaa

8/9/2018 11:31:47 am

Speaking of unprecedented political extremism I wonder if this blog will also mention what happened to Tommy Robinson and Alex Jones. Those of us who lived in former Soviet Union find such cases all too familiar. What next for Alex Jones if he still does not shut up? Mental hospital and heavy drug dosages?

Reply

An Anonymous Nerd

8/9/2018 06:37:45 pm

Reply

Americanegro

8/9/2018 08:46:27 pm

"Professor Herbst fails to notice a glaring difference, however: The police were hunting the Socialists, whereas the Libertarians, though contrarians to a degree, weren't hunted by the police. They were legal and accepted."

Aaa

8/10/2018 03:25:58 am

_It isn't really Mr. Colavito's thing. He's addressed some of Mr. Jones's bunk a time or two.__

An Anonymous Nerd

8/11/2018 11:57:15 pm

[_It isn't really Mr. Colavito's thing. He's addressed some of Mr. Jones's bunk a time or two.__

Mrs Grimble

8/12/2018 12:58:46 pm

"I know little of Tommy Robinson".

An Anonymous Nerd

8/12/2018 02:13:07 pm

[ In short, he's a grifter and a scammer who is taking the American right-wing for a ride. ]

Americanegro

8/9/2018 01:38:43 pm

Like Biskind and "extremism" you're mixing two different meanings of "conservative". Might as well add a third: the universe itself is conservative because of conservation of energy.

Reply

8/9/2018 01:57:32 pm

WWII devastated the global economy and left America in a position of power.

Reply

Machala

8/9/2018 02:54:29 pm

" We are speaking here of the 1950s when government efforts to sanitize media were at their height. "

Americanegro

8/9/2018 03:24:26 pm

I hope that during my lifetime we can retire the term "witch hunt" as applied to McCarthy. If the Russians had a spy in the Manhattan Project (Fuchs, not Oppenheimer) is it really a stretch to think they had a few in the other parts of gummint?

A.Rose

8/9/2018 11:59:34 pm

"...There have always been partisan divides. ..."

Shane Sullivan

8/10/2018 01:57:18 am

A. Rose, you might want to look up John Stuart Mill. And Jeremy Bentham. And Francis Hutcheson. And Hierocles. And Mozi.

Americanegroo

8/9/2018 02:52:21 pm

Truck.

Reply

8/9/2018 03:01:51 pm

What exactly are you arguing here? We aren't talking about the Soviet Union's media but America's, so it isn't relevant. The Third World wasn't economically important then, either.

Reply

Americanegrotusi

8/9/2018 03:14:30 pm

"What exactly are you arguing here? We aren't talking about the Soviet Union's media but America's, so it isn't relevant. The Third World wasn't economically important then, either."

Machala

8/9/2018 05:48:19 pm

"In the 1950s, government regulated media more heavily than they do today. They also launched campaigns to "clean up" the media. Remember the anti-comic book hearings of the 1950s?" 8/9/2018 08:10:18 pm

I know it wasn't government-regulated. The whole point is that government used the threat of regulation, public bullying, etc. to accomplish regulation, but such efforts broke down in later decades when official regulatory powers declined in the wake of free speech court cases and publishers became less willing to play along with government requests.

An Anonymous Nerd

8/9/2018 07:51:53 pm

Based upon this review, I guess the best word to describe the argument of this book is "exaggerated."

Reply

GodricGlas

8/9/2018 10:46:33 pm

Once when I was in a used CD rom store, many, many years ago, I found the complete Monty Python’s Flying Circus collection (A&E) sitting on the shelf and I picked it up for a sweet deal.

Reply

G

8/9/2018 11:02:04 pm

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=ut82TDjciSg

Reply

"rational skeptics"

8/10/2018 01:22:50 am

Jesus christ, what's with all these "skeptic" forums and comment sections being taken over by batshit crazy right-wingers and religious nuts? Are Alex Jones and Jordan Peterson now considered "rational skeptics"?

Reply

G

8/10/2018 01:33:48 am

This is way more than a “skeptic-forum”.

Reply

G.Glas

8/10/2018 01:40:03 am

No! Wait!

Americanegro

8/10/2018 02:50:25 am

Have you considered using one pseudonym consistently?

GodricGlas

8/10/2018 09:47:24 pm

That’s probably a good idea.

The most stupid thing ever invented

8/10/2018 05:58:14 am

A historical humanoid Christ by second century Christians

Reply

Indeed

8/10/2018 06:05:05 am

That story of Jesus Christ crucified "by Pilate"

Reply

An Anonymous Nerd

8/12/2018 02:48:55 pm

According to National Geographic Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed