|

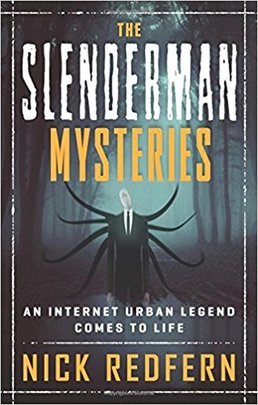

THE SLENDERMAN MYSTERIES Nick Redfern | 2018 | 288 pages | New Page Books | ISBN: 978-1-63265-112-9 | $15.99 In 2009 a man named Eric Knudsen created photo art of a thin, mysterious supernatural man in a suit, and he posted these photo illustrations to Something Awful, where they became the fodder for countless online stories of a creature soon known as Slender Man, sometimes stylized as Slenderman. In this, it was not entirely different from the fictitious Blair Witch of 1999, or the Cthulhu Mythos of H. P. Lovecraft’s fiction. In each case, a fictitious creation came to be embraced as “real” by fans who should have known better. The story of Slender Man is important, however, because in 2014 two 12-year-old girls lured a third into the woods in Waukesha, Wisconsin and stabbed her 19 times in an effort to impress the Slender Man. The victim survived, but the perpetrators were found not guilty by reason of insanity. Each was sentenced to decades in a mental health facility. The incident undercuts the collective “fun” to be had from pretending a fictitious thing was real. This dark chapter in the otherwise mostly unremarkable history of the Slender Man character hangs over Nick Redfern’s new book, The Slenderman Mysteries (New Page, 2018), and it cuts against his usual tone of slightly uninterested good humor. Redfern dutifully but briefly reports the story in his introduction before reveling rather obscenely in its gory details in chapter 6 and letting the story shape the second half of the book in unsettling ways. Here, though, he merely calls it “extremely disturbing,” and lets the incident pass mostly as a curiosity on the road to the “fun,” which for him is the question of whether Slender Man, like the incorporeal thought entities called egregores in Victorian magician Éliphas Lévi’s (fake) occult mythology, is really some sort of sentience called into being from human desire, the internet’s growing consciousness, or a supernatural realm: More and more people are following, and arguably even worshiping and devoting their lives to, the Slenderman as he becomes ever stronger and more physical in our world. Where did he come from? What does he want from us? What are the many witnesses to the Slenderman telling us? Is there just one creature, or are we looking at multiple Slendermen? How can we stop him from terrorizing and torturing us? Can we stop him? Or has he become an unstoppable, unbeatable nightmare?  These questions are inappropriate, both because the fiction has had terrible real-world consequences and because by any objective measure the Slender Man has no physical reality, and no will or desire. To lay the issue out at the most basic level, the Slender Man’s influence is no different than, say, an Islamic State suicide bombing manual. The Islamic State may have goals and desires, but the manual does not, even though its readers are inspired to kill from reading it. The manual is just a piece of media; it did not make them do it, nor does it have any independent power of action beyond that of the authors who wrote it and the readers who consume it. Slender Man is little different, except that he has a vaguely anthropoid form, which allows his consumers to attribute to him motives and desires that simply are not there. This is why Redfern’s first chapter, tracing the well-established chronology of the Slender Man’s early history, from the first photo illustrations to the earliest fiction written about him. But near the end of this chronology, Redfern notes than in November 2009, irresponsible Coast to Coast AM host George Noory (a colleague of Redfern’s on Ancient Aliens) played host to a number of callers who claimed to have encountered the Slender Man. But Redfern is uninterested in establishing the truth of these claims, perhaps because Coast to Coast is such an important station of the cross on the fringe publishing circuit: Some might suggest that the people who phoned in to Coast to Coast AM were hoaxers. Maybe they were, maybe they weren't. But it doesn't really matter. If enough of the Coast to Coast AM audience believed what they were hearing, then that collective and combined belief would have gone a significant way toward ensuring that the Tulpa version of the Slenderman would soon be up and running. A tulpa? Yes, of course. The author has a habit of dropping in people and concepts without explanation before reversing course at a later point and circling back to explain them. Redfern devotes the next chapter to discussing the term, which he introduces at first as a Buddhist concept. The tulpa as we know it today, and as he is using it, is a theosophical concept from the 1920s—not even a century old!—in which thoughts can manifest in forms that influence the physical world. It is a garbling of the Tibetan Buddhist concept of sprulpa and/or tulku, whereby celestial beings and some humans can create astral bodies or spiritual manifestations. Theosophists applied this to the generation of three types of “thought-form,” an astral projection of the thinker, the embodiment of a spirit or deceased soul, or the manifestation of an emotion. But Hollywood misunderstood even this, and episodes of shows like The X-Files (“Arcadia,” Mar. 7, 1999 and “Home Again,” Feb. 8, 2016) and Supernatural (“Hell House,” Mar. 30, 2006 and “#thinman, Mar. 4, 2016) expanded the tulpa concept to include the involuntary manifestation of a monstrous being, basically by necromancy. In the case of Supernatural’s “Hell House,” which is most directly relevant here, the imaginary action involved a fake internet legend of the fictitious killer Mordechai Murdoch coming to life as a ghostlike and violent monster simply because enough people believed in him, and some magic squiggles were painted on the walls, since in the show’s world symbols have power regardless of whether the writer understands them. While Supernatural did not invent the claim of involuntary tulpa creation--authors as diverse as Sylvia Browne and Michael Grosso used it in the 1990s and early 2000s, though not with the mass media angle--it surely popularized it. Here, Sam and Dean Winchester, the monster hunters, discuss tulpas: Sam: So there was an incident in Tibet in 1950. A group of monks visualized a golem in their heads, then meditate on it so hard, they bring the thing to life out of thin air. Compare this to Redfern’s words alleging that a May 2014 Coast to Coast AM broadcast mentioning Slenderman was responsible for the stabbing that occurred a few hours after the show ended: That Coast to Coast AM has such a phenomenally massive number of listeners may also have had a bearing on how and why the Slenderman controversy reached its terrible peak only a handful of hours after the show aired. More listeners equals more believers. More believers equals a more powerful, dangerous, and corporeal Slenderman. In the current book, Redfern has compressed the entire history of tulpas into an assumption of belief, even though his working thesis of the Slender Man is ripped almost verbatim from “Hell House.” However, in the first half of the book Redfern treats the modern myth of the tulpa as though it is a genuine and ancient form of sorcery, going so far as to say that “All too often they have a disturbing habit of running riot and turning against their creators.” This is less an ancient mystical tradition than a claim made by Alexandra David-Néel, a Belgian-French Buddhist in her 1929 book Magic and Mystery in Tibet, where basically the same claim appears (and which Redfern later quotes): “Once the tulpa is endowed with enough vitality to be capable of playing the part of a real being, it tends to free itself from its maker’s control. … Sometimes the phantom becomes a rebellious son and one hears of uncanny struggles that have taken place between magicians and their creatures…” Tighter editing would have eliminated the redundancy of summarizing and then quoting the same material. Evaluating the accuracy of this report is problematic because there is so little information in English that isn’t written by New Agers. I searched several academic databases and found nothing. It’s interesting, though, that the information David-Néel gives is recounting rollicking legends—basically ghost stories—rather than pointing to articles of faith. That said, she claimed to have created her own evil tulpa, which haunted her for a long time. Given that no one else could confirm the existence of this supposedly partially corporeal creature, the most parsimonious explanation is that she had convinced herself of a fantasy. I’m also concerned that her account of the tulpas seems to stand behind every other, with little or no effort to replicate her research. Redfern accepts her claim at face value and suggests that Slender Man is also a creature called into being by internet belief. Citing Vice.com as his source, Redfern wrongly concludes that the tulpa was largely unknown outside of occult circles until 2009, the same time that Slender Man emerged, a coincidence he sees as significant. However, as we saw, The X-Files and Supernatural had popularized the tulpa--Supernatural more than any other—among the same internet geeks who birthed Slender Man and who engaged in what Vice.com said was a group effort among 4chan members to create tulpas as imaginary friends. It’s important to note a very important difference: Before Hollywood took over, a tulpa was typically created intentionally through specific magical rituals and for specific purposes. (Redfern very briefly notes this in the conclusion.) Afterward, there was an explosion of books in which a tulpa became any kind of psychic projection, called into being by the will to believe. This seems more of a reflection of the postmodern view of religion as a collective construct (or the common science fiction/fantasy trope that ghosts and gods exist only because of those who believe in them) than a genuine Tibetan tradition. Redfern tries to support the reality of manifesting spirit beings by citing people who claim to have encountered them. In one case he literally tells us that the encounter took place while the viewer was in a “state of semi-sleep,” making quite clear that the most likely explanation is a waking dream. I’ve had them myself, so I understand how they can seem quite real. Weirdly enough, Redfern later quotes occult researcher Ian Vincent to the effect that the tulpa is a modern, bastardized, misunderstood concept with little connection to Buddhism, but he lets this slide by without comment. As with much of the Redfern oeuvre, the accounts are presented at face value, with little critical analysis, in service of a thesis—that Slender Man is something like a tulpa—that is stated in the conditional tense (“…may have…” “…might…”) so that the author never quite commits to the thesis, lest he be accused of making a claim his surface-level research can’t support. And yet, the reader is clearly meant to take this suggestion seriously, for as the book progresses, Redfern delves ever deeper into the opinion of occultists that the Slender Man has achieved sentience through the magical power of belief. He moves away from tulpas to enter into the realm of ceremonial magic, particularly the strain of evidence-free magical thinking that claims H. P. Lovecraft was in subconscious contact with transdimensional supernatural entities and therefore the Cthulhu Mythos was in some sense “real.” This is, of course, the view of Kenneth Grant, but the fact remains that it is rank speculation born of a belief in the power and efficacy of magical rituals, even if Redfern declares chaos magic to be a “very plausible explanation” for how the Slender Man might become real. Redfern, however, feels that it is highly significant that Grant used Lovecraft for magic, while Slender Man’s creator, Eric Knudsen, claimed to have been partially inspired by the atmosphere of Lovecraftian horror in developing the first Slender Man photo illustrations and their accompanying captions. This is testimony not to channeled power from the spirit world but to the pervasiveness of Lovecraftian fiction among those inclined to the weird. Lovecraft, after all, turned to Éliphas Lévi’s work on the occult and magic in crafting his own tales of dark powers, so there is a perfectly material explanation for how egregores translated from Lévi to both Lovecraft and modern occultists and then to Slender Man, whose creator and advocates drew on both. But for Redfern this is not nearly as good a story as imagining that egregores or tulpas are real. It is this defiant desire to absolve the actual human proponents of Slender Man’s ersatz mythology of responsibility for their own actions that leads Redfern to some inexcusable efforts to portray the stabbings committed by those preteen girls in Wisconsin as the result of supernatural forces. In the sixth and seventh chapters, Redfern dwells in almost prurient detail on the lives of the girls who stabbed their friend in Slender Man’s name, essentially exploiting the mental illness of the ringleader in order to promote an irresponsible allegation that the girls were involved with a real supernatural entity. The chapters are a condensation of Beware the Slenderman, a 2017 HBO documentary that dealt more seriously with the fallout and important lessons of this crime. Here, though, Redfern strip-mines to documentary for nuggets of sensationalist garbage he can spin into supernatural proof. For example, one girl claimed to have dreamed of Slender Man at the age of three, which was before the character’s creation. Rather than explain that as a child’s fantasy, or a faulty memory of visually similar characters like the Gentlemen from Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1999) or Pale Man from Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), Redfern declares this to be “eye-opening” proof of Slender Man’s reality. He also does his math wrong. The girl was twelve in 2014, so she was three nine years earlier, in 2005 or 2006, not 2000 as Redfern alleges. This becomes more maddening when Redfern acknowledges similar situations that have occurred in pop culture, such as Pan’s Labyrinth, but calls them “synchronicities” that suggest a supernatural reality rather than, as is much more likely, pop culture drawing on earlier weird and occult literature and in turn influencing those who consume it. Because he doesn’t give this serious consideration, a chapter devoted to scaremongering summaries of various teenagers’ acts of violence and vandalism in the name of Slender Man, violent videogames, and other media products rings both false and exploitative, a moral panic (an important phrase never once appearing in the book) that Redfern accepts as legitimate without interrogating the underlying meanings and motives. These aren’t bonkers money-grubbing adults like the cast of Ancient Aliens whose choices are ripe for exploitation because they chose to exploit themselves; these are disturbed children who ought not to be used to sell supernatural snake oil. When Redfern ends a description of alcoholism and suicide among Native American youths on the Pine Ridge Reservation with the gleeful words “You know what—or, rather, who—is coming” before trying to claim Slender Man (or its Native interpretation, Tall Man Spirit) as a cause rather than a symptom of the complex psychological and socioeconomic issues involved, it, frankly, angered me. What makes it worse is that Redfern’s many chapters giving litanies of similar stories are almost entirely summaries of newspaper articles and web chatter, with virtually no original analysis—or even much of a point—to justify exploiting damaged children. This is merely copy-and-paste rubbernecking. To his credit, Redfern understands this, though he immediately chooses to discount the objection: Blaming such tragic events on the actions of a supernatural entity that we cannot fully prove exists is as reckless as it is, for many, both unbelievable and inappropriate in the extreme. While it’s all too easy to see evil in every corner, more often than not that evil comes from us, not from murderous monsters. Others, though, and particularly those who have encountered the faceless beast close up, might disagree with that particular point of view. Given the sheer fear that such encounters generate, it’s easy to see why some might suggest that the Slenderman has indeed manipulated people to commit violent, murderous attacks. Maybe it has done exactly that. Having his cake and eating it, too, Redfern wants credit for recognizing that his book is offensive and exploitative, while still engaging in that offensive exploitation. You can’t have both. Near the end of the book, Redfern approaches Slender Man ass-backward, looking for older myths and legends that have some similarities to the ersatz story of Slender Man. Instead of understanding that the modern Slender Man fakelore draws on elements of older stories, he wrongly tries to argue that unrelated and largely different myths are actually Slender Man himself. Thus, the incongruity of arguing that the Pied Piper of Hamelin, who had a face and spoke, is also the silent, faceless Slender Man. Similarly, he falls into the trap of backward attribution, collecting ex post facto accounts from Waukesha, Wisconsin of people meeting dark shadows in the woods, Slavic immigrants’ imported tales of the vodyanoy (a frog-monster better known to me as the Polish wodnik), and stories of actual unsolved child murders from the area in order to claim that Slender Man is behind them, implicitly absolving the girls of their actions. Oddly, Redfern is happy to attribute any story, even those of UFO lore, involving tall men in black to Slender Man but seems ignorant of the American Puritan forms of Satan made famous as the Black Man of the woods in Hawthorne’s Scarlet Letter and “Main Street” and in Lovecraft’s fiction. The allusions to the Black Man are, as should be obvious, an influence on the dark, tall, evil figures of pop culture. Perhaps the Black Man is too sophisticated for Redfern’s thesis. Here is Hawthorne describing him in The Scarlet Letter: “How he haunts this forest, and carries a book with him, — a big, heavy book, with iron clasps; and how this ugly Black Man offers his book and an iron pen to everybody that meets him here among the trees; and they are to write their names with their own blood. And then he sets his mark on their bosoms!” But, really, isn’t that the Slender Man with an analog internet? Redfern is suitably impressed that some people described “perfectly” (ha!) the Slender Man before its 2009 creation, though by “perfectly” he means three things: tall, wearing a suit or coat, and having no face. This, he feels, is beyond the realm of possibility if Slender Man were not real, since he has apparently forgotten pop culture characters like Charlton Comics’ (now DC’s) The Question (created 1967) or Dick Tracy’s The Blank (created 1937), both of whom answer to the same description. The remainder of the book recounts various modern individuals’ alleged encounters with creatures that resemble Slender Man, from the last few years when the meme was well-known. Even Redfern notes that many such encounters occur when the victim is falling asleep, though he discounts the fact that this is the time associated with waking dreams. He also compares the Slender Man to Lovecraft’s night-gaunts, which is strange since those creatures were basically flying stingrays and look nothing like a dark man in a suit hanging out in the woods, which was more Nyarlathotep’s thing. At the most basic level, Redfern is trying to force comparisons into a box that doesn’t quite fit since it is built on the shaky foundation of the Slender Man being the prototype of ancient evil rather than a modern fiction.

The book ends with a series of rhetorical questions designed to leave the reader with the impression that Redfern has said something about the Slender Man, when he has not. It is symptomatic of the failures of the book, which in the end is a superficial collection of other fringe writers’ views wrapped in salacious anecdotes and irresponsible speculation in the form of “just asking questions.” This reaches the heights of ridiculousness when Redfern speculates that Slender Man is actually an Agent Smith figure because we live in a simulated Matrix-like universe. If that is the case, he is a terrible secret agent of the Machines. The Slenderman Mysteries suffers from the typical weaknesses of a Redfern effort. It is overwritten, with sentences spiced with redundancies and the same ideas repeated more than once. It is chock-a-block with block quotes, many of excessive length, held together with the thinnest of connecting thoughts. It relies nearly exclusively on other fringe books and websites, as well as selectively excerpted magazine and newspaper articles, with hardly a hint of research in scholarly sources. I’m sorry, but chaos magicians and Coast to Coast AM are not reliable sources, nor are their conclusions based on anything like verifiable evidence. In many cases, they don’t even understand the history of their own claims, and when we add Redfern summarizing and repeating these speculations, we merely add another layer of garbling and confusion. Even the original interviews Redfern conducted are less than illuminating, talking to chaos magician Ian “Cat” Williams and “paranormal pastor” Robin Swope, neither of whom contribute anything of value not already in the published literature on the subject. Redfern has not quite mastered the idea, laid out decades ago by Lawrence E. Spivak, that interviews are most illuminating when the interviewer challenges the subject with opposing views. In the end, the book boils down to a bunch of fantasists trying to parse the hairline differences between egregores, transdimensional entities, tulpas, thought-forms, and archetypes without ever once bothering to discern whether there is reason to attribute any reality to the Slender Man beyond the universal human tendency to displace acts of evil onto outside forces and ritually purify the perpetrators of their sins. No one involved wants to admit that preteen girls are less than innocent, and so a tulpa becomes a more reasonable explanation than the idea that children can harbor serious mental illnesses and even amorality or evil.

68 Comments

Nick Redfern

3/6/2018 09:56:58 am

If I were to get into a debate on all this, I just know I would be doing it for the next week. Maybe more. And for various reasons I don't have time anymore to endlessly argue and debate here throughout the day as I could in the fun days of last year and earlier years. As much as I enjoy a good online argument/rant here at this blog for hours at a time, time's now against me. So, I'll sum things up like this:

Reply

Gunn at Risk

3/6/2018 10:15:47 am

I tell it as I see it, too. Let's not forget the very real Devil angle in all this, gentlemen...the evil twisting and lying and harm, which is his specialty:

Reply

A Buddhist

3/8/2018 08:56:15 pm

Satan is a better sort than YHVH your god in terms of not killing: http://dwindlinginunbelief.blogspot.ca/2009/01/who-has-killed-more-satan-or-god.html

E.P. Grondine

3/6/2018 11:38:31 am

“Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn't go away.” ― Philip K. Dick

Reply

Nick Redfern

3/6/2018 02:02:57 pm

OK, I'm back for about 45 minutes, so a few quick replies:

E.P. Grondine

3/6/2018 11:18:25 pm

Like I said, Nick, it's all a lot of fun until the bodies start piling up:

E.P. Grondine

3/7/2018 10:18:10 am

Hi Nick -

Bob Jase

3/6/2018 12:24:31 pm

Some people will believe anything.

Reply

I KNEW THE FAMILIES INVOLVED.

3/6/2018 01:47:45 pm

HOPE YOU ENJOY THE MONEY YOU MAKE OF THE TRAGIC GIRL'S STORY, YOU HEARTLESS BASTARD.

Reply

Nick Redfern

3/6/2018 02:09:00 pm

Huh? What the fuck are you talking about??? I told the story of how the attack / stabbing by the girls occurred, the court case, the questioning by the police etc in a timeline style.

Machala

3/6/2018 02:33:11 pm

Nick Redfern said:

Pacal

3/6/2018 04:33:17 pm

"Money? In the field of writing paranormal books? Are you serious? Don't make me laugh. If there is only one thing me and Jason CAN agree on it's that if you want to earn good money do NOT write on the world of the paranormal!"

Pacal

3/6/2018 04:18:43 pm

"I do fully believe in the thought-form concept."

Reply

BigNick

3/6/2018 04:38:08 pm

It's actually the biggest load of nonsense. I write Santa's name on gifts for my kids at christmas, but millions of kids believe in Santa. You can't completely disprove aliens, ancient or otherwise, but to me this is clear evidence that this whole Tulsa thing is b.s. disprovable b.s.

Nick Redfern

3/6/2018 06:36:21 pm

All I can tell u for sure is that me and my friends in the field of paranormal writing do not generate much of an income. We do it because we want to.

Nick Redfern

3/6/2018 06:39:56 pm

Bignick: You say "this whole Tulsa thing is b.s.disprovable b.s." I doubt the people of Tulsa would agree. You mean Tulpa NOT Tulsa. Geeeeezzz...

BigNick

3/6/2018 06:41:42 pm

But if we all believe you make lots of money, shouldn't that make it real? I'm not mocking your stupid theory, I'm trying to understand.

BigNick

3/6/2018 06:56:00 pm

Autocorrect got me twice today.

Nick Redfern

3/6/2018 10:29:04 am

I have about 30 minutes before it really is time for me to move on, but here's the situation: (1) what you call "twisting" is actually me giving my honest views that others may significantly disagree with. (2) I don't lie. People may not agree with what I say and I may have some seriously weird beliefs (I certainly do), but that's not lying. (3) I don't do "harm."

Reply

3/6/2018 10:53:48 am

I believe that Gunn (Bob Voyles) was referring to the Devil, not you, as lying and twisting.

Reply

Bob Jase

3/6/2018 03:49:18 pm

If thoughts created actual beings then wet-dreams would have caused the world to collapse under the weight of beautiful imaginary women centuries ago.

Gunn at Risk

3/6/2018 06:39:45 pm

Thank you. Yes, I, was referring to Satan, the evil angel who revolted against his own Creator. Like millions of Christians worldwide, I believe in good angels and bad angels. God leads the good angels and Satan leads the bad angels. Spiritual warfare is constantly taking place all around us. These spirit beings either try to harm us, or they try to intervene on our behalf, depending on which master/Master they serve.

A Buddhist

3/8/2018 09:06:08 pm

Gunn at Risk:And yet according to your own scriptures, YHVH lying spirits, evil spirits, and killing spirits to people. 3/6/2018 06:50:42 pm

BN: No, of course that won't work, that's the craziest thing I have heard in a long time! When people try and create a thought-form they are trying to create some form of "life," not to supernaturally print wads of cash!

Reply

Jane Smith

3/7/2018 11:38:40 am

Mr. Redfern, "...whatever you, me, or anyone else believes" should be "whatever you, I, or anyone else believes". "...me and Jason" should be "Jason and I". "...me and my friends" should be "my friends and I". "...me giving my honest reviews" should be "my giving my honest reviews". You are welcome.

Reply

Nick Redfern

3/7/2018 11:59:00 am

Who the hell cares how a few words appear in a comment box? No-one says "My friends and I." Maybe the cast of Downton Abbey.

Stickler

3/7/2018 12:08:42 pm

If you said that to I IRL me would punch you in your face.

Nick Redfern

3/7/2018 12:17:01 pm

Stickler: Have at it!

A Buddhist

3/8/2018 09:09:36 pm

Jane Smith: Fellow lover of proper grammar, I salute thee.

Nick Redfern

3/9/2018 09:35:41 am

A Buddhist: My point is this:of course good grammar is required in a book or an article. But, when you're just responding to a blog post, it doesn't really matter if I write "u r" vs. "you are." Etc etc.

A Buddhist

3/9/2018 07:40:53 pm

Mr. Redfern: That is certainly your right. But I, who find writing so difficult, strive never to have written something that is not grammatically perfect. To do otherwise would be to turn my effort into a travesty of virtuous striving.

Stickler

3/9/2018 09:44:09 pm

Since you can't control the past, why don't you "strive never to write blah blah" instead? I understand that "to have written" takes place in the present, but The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ, Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line, Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.

Nick Redfern

3/6/2018 11:06:05 am

Jason, maybe we are, but perhaps we just dont see them for what they are. Or most people don't.

Reply

Americanegro

3/6/2018 02:06:41 pm

Is Nick Redfern the guy who talks about hitting people? Anyway The Bunnyman could beat the Devil and Slenderman in a fight because The Bunnyman is real.

Reply

BigNick

3/6/2018 03:36:21 pm

I think Nick Redfern is the guy that married Joanie Caucus.

Bob Jase

3/6/2018 03:51:23 pm

"because goatman has an ax."

Clete

3/6/2018 12:10:38 pm

Jason, really, two Nick Redfern mentions in less than a week. I mean, it seems that a lot of the fringe community is no longer doing much, but surely someone out there is doing something more than publishing "The Slenderman Mysteries".

Reply

Only Me

3/6/2018 01:04:53 pm

The X-files episode, "X-Cops" (February 20, 2000), played on a similar theme to the tulpa.

Reply

Jesus Christ

3/6/2018 02:33:08 pm

God Bless You, Only Me

Reply

That's It

3/6/2018 02:34:33 pm

We have a believer in the pseudo history of the gospels attacking the pseudo-history of Nick Redfern

Jesus Christ

3/6/2018 02:35:41 pm

I am the King of the World

Watch Out

3/6/2018 02:38:00 pm

Only Me is protected by the Blog Owner and will delete messages.

Only Me

3/6/2018 02:51:17 pm

If I'm "protected" and your comments are going to be deleted, why are you wasting your time?

Reply

David Bradbury

3/6/2018 02:54:15 pm

The idea of supernatural beings created and fuelled by human belief goes back at least to A.E. van Vogt's "The Book of Ptath" (1943)- with Pterry's Gods being a later satirical variant.

Reply

David Bradbury

3/6/2018 02:56:03 pm

Oops- the words "in fiction" should go after "beings" there.

Shane Sullivan

3/6/2018 01:26:37 pm

I remember tulpas being the subject matter in an episode of Disney Channel series So Weird when I was a kid. That was where I first heard the word.

Reply

Machala

3/6/2018 01:55:45 pm

As always, Jason, an interesting revue. This is one that I'm not forming any opinions on until I've had the opportunity to read Mr. Redfern's book en total, which I'm going to try to do, at first opportunity. In the mean time, I am enjoying reading the commentary.

Reply

A Buddhist

3/8/2018 09:14:44 pm

Dhammapada:

Reply

Tulpas "R" Us

3/6/2018 03:31:43 pm

Jason it would be cool to see a review of something you enjoyed or think is highly rated. Would be interesting along with your other critiques.

Reply

Jim

3/6/2018 03:59:45 pm

No worries, I have it on good authority, The Shadow has already taken care of the thin man.

Reply

BigNick

3/6/2018 04:23:46 pm

Wasn't this Tulsa thing the plot to Rise of The Gaurdians?

Reply

Kal

3/6/2018 04:29:09 pm

Tulpahs are an old concept from the 20s, possibly older, and tall evil figures have been around since at least then.

Reply

Bob Jase

3/6/2018 05:00:32 pm

The song was inspired by the film.

Reply

Jane Smith

3/7/2018 05:23:38 pm

Mr. Redfern, You are a professional writer. Your grammar should be perfect.

Reply

Machala

3/7/2018 07:00:05 pm

Ms. Smith,

Reply

Jane Smith

3/8/2018 02:05:02 pm

Dear Machala, Thank you for your courteous and well thought-out email. I am concerned with the destruction of the English language. Why is using correct grammar such a huge and inconvenient task? Why isn't it second-nature? If it is a little more difficult, why aren't others worth it? Ideas gain credibility when expressed well, and lose credibility when they aren't. They are also easier to understand and a joy to read. I try to speak and write correctly as a courtesy to others. It shows that I value and respect them. I didn't expect to start a discussion, and am surprised at the reaction against good grammar. (But then, I was one of those oddballs who diagrammed sentences for fun)

Machala

3/8/2018 03:11:19 pm

Ms.Smith,

Nick Redfern

3/8/2018 09:36:57 am

No, not for when I'm quickly writing a few comments at a blog and juggling my day job. People can figure it out.

Reply

Joe Scales

3/8/2018 10:40:15 am

Day job? Oh right... ghost-busting is for nighttime.

Clete

3/8/2018 10:43:34 am

You finally have a day job, well good for you. As for your writing and research, I can now use a phrase that would apply. Don't quit your day job.

Nick Redfern

3/8/2018 10:50:43 am

No, not that kind of day job you mean. Writing is my day job. I strictly work 9-5 Monday to Friday writing the books, articles, etc. I don't work evenings or evenings. So that's what I mean by my day job: regular hours. I always call it my day job because for me that's exactly what it is.

Reply

Joe Scales

3/8/2018 02:22:56 pm

Writing? If it were properly labeled as fiction, then certainly you could consider that sort of writing a job. Otherwise, it's better described as a number of other things. Scamming, swindling, misleading, cheating, faking, hoaxing, deceiving, fooling, lying... well, those are some that quickly come to mind.

Reply

Nick Redfern

3/8/2018 02:55:47 pm

Dead wrong. I don't lie. I don't fake. I don't hoax. I don't swindle. But I have been hoaxed myself and I have been lied to. I doubt there is anyone in paranormal research who hasn't been hoaxed or lied to on at least a couple of occasions.

E.P. Grondinw

3/9/2018 04:56:02 pm

Hi Nick -

Nick Redfern

3/8/2018 10:52:15 am

I meant "evenings or weekends."

Reply

Nick Redfern

3/8/2018 10:56:27 am

And that's what I meant in this thread about me not bothering about my grammar being perfect in a blog comment. Writing is my day job, and as I work 9-5, Mon-Fri on the books etc it means I sometimes I have to race thru these comments so I'm not forced to work evenings etc.

Reply

Jane Smith

3/8/2018 07:15:50 pm

Machala, I agree with you. Language certainly does change. I don't think I would like to plow through an original Chaucer. I, too, love words. Language is powerful because we use it to transmit ideas. It's also available to everyone. Helen Keller is a good example. Besides diagramming sentences for fun, I also devoured the thesaurus. My favorite word was sesquipedalian. Ah, was I ever that young?

Reply

Amanda

3/24/2018 10:12:31 pm

I hate to admit this, but I've been a member of Something Awful for years and was around for Slenderman's creation. He was created to troll a site that posted "real" paranormal photos. The Slenderman photos were by far the best submitted to the thread and other goons fleshed out the story beyond what the original poster had written. From there it spread to other sites.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed