|

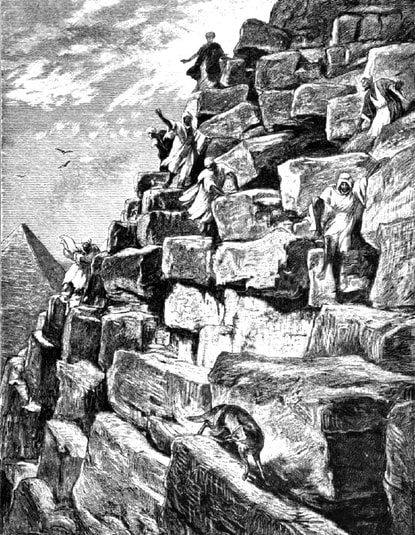

A little while back, I wrote about the so-called “Exposure at Vienna,” when in 1884 Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria developed a scheme to expose the American medium Harry Bastian as a fraud. I wrote about that because I had learned of the upcoming release of Greg King and Penny Wilson’s new book Twilight of Empire, about Rudolf’s suicide. On a whim, I wrote to St. Martin’s Press, the publisher of the book, and they kindly provided me with an advance copy, which I am now reading. My initial glance at the book was a bit disappointing in that the authors summarized Rudolf’s entire life in a few pages before moving on to the denouement, and they seem, from what I have read in the first half of the book, to have painted him as a mostly unmitigated villain. The truth is that his life was closer to a supervillain’s origin story, a brilliant potential undone by tragic flaws and the indifference of the world around him, until the final, mad, murderous end. Imagine blue skies gradually filling with storm clouds. I will have more to say about this when I review Twilight of Empire, but I don’t believe one can really evaluate the end of Rudolf’s life without understanding what came before. Anyway, in doing my background reading in preparation for reviewing the book, I found that Rudolf had made an interesting journey to Egypt, where he encountered the pyramids and temples, and which helped develop the skepticism that led to his attack on Bastian a few years later. Since this adventure is given all of half of one sentence in Twilight, it might well be one worth telling in full. Plus, it gives me a chance to show off that I can use more primary sources in a blog post than King and Wilson did in the entire chapter on Rudolf’s life prior to Mayerling—a life they seem to condense down to its worst anecdotes to better cast Rudolf in villainous light. Before we begin, you might want to read Rudolf’s own account of his time in Egypt, which I have posted in my Library. On February 9, 1881, Rudolf set off from Vienna on a months-long excursion to Egypt and the Holy Land, with the object visiting the usual tourist spots, doing some hunting, and conducting a goodwill tour of the Ottomans’ Asian and African possessions. The unspoken undercurrent of the trip was Austria-Hungary’s occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, an Ottoman province, under the terms of the Congress of Berlin. At the same time that Rudolf was chatting up the Khedive and other Ottoman officials and generally making a good impression, the Austrian government signed a treaty approving the annexation of Bosnia at a future date. Rudolf is silent on the diplomatic import of his vacation in the book he wrote about it, Travels in the East (1881, English trans. 1884), but it is likely not coincidental that an Austrian archduke toured the Ottoman Empire only weeks before the annexation treaty was signed. Before leaving on the trip, Rudolf planned ahead to make use of the adventure for scientific and literary purposes. He hired an illustrator, Franz Xaver von Pausinger of Salzburg, twenty years his senior, to travel with him and document the sights. He also wrote to the eminent German Egyptologist Heinrich Karl Brugsch, who was that year made a pasha by the Ottoman Khedive. Rudolf had met Brugsch, 32 years his senior, at the 1878 Vienna Exposition, and he had heard good things about Brugsch from his father, the Emperor, who employed his services when he had toured Egypt for the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal, when, because of rank and precedence, as the highest ranking European monarch, he had had the privilege of following the Empress Eugenie’s yacht through the canal at the opening. Brugsch had taken Emperor Franz Joseph on a climb to the top of Khufu’s pyramid, and Franz Joseph had almost no reaction. Brugsch recalled jokes that his ministers made, but nothing from the emperor. In a letter to the Empress Elizabeth, Franz Joseph merely recalled that the Bedouin guides who helped him climb up tended to leave their shirts open, and that must be why “English women so happily and frequently like to scale the pyramids” (trans. Alan Palmer). Twelve years later, Rudolf wired Cairo to ask Brugsch to assist him, and Brugsch, out of a job thanks to politics, and in hope of gaining new luster for his reputation, dutifully accepted. Brugsch’s great friend, the even more eminent Egyptologist Auguste Mariette, had just died on January 19, and Brugsch harbored hopes that he might succeed Mariette as the Director of Antiquities at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. This was not to be. Mariette had, on his death-bed, arranged for Gaston Maspero to take over to retain French primacy in Egyptology. Brugsch later fumed about the slight in his 1894 autobiography, appalled that nationalism should triumph over the bonds of friendship and scholarly qualification: “The Egyptian government and the Khedive let themselves be intimated, and my own person which, according to the intention and the declaration of the Viceroy himself, alone possessed the right of succession, was pushed back for the sole reason that I had the honor to be a German, and only as such to displease the great nation” (trans. George Laughead Jr. and Sarah Panarity). This latest snub came on the heels of French orders to fire most of the staff of the School of Egyptology, in the name of cost-cutting. By comparison, Rudolf’s patronage seemed to flatter Brugsch’s sense of self-importance. The prince, he later wrote, “understood how to recognize my humble services.” Rudolf’s active mind flitted from subject to subject as his yacht, the Miramar, wound its way down the Adriatic. Many later writers thought this evidence of an undisciplined, inconsistent mind, but Rudolf was all of 22 years old. Rigorous consistency comes later. At Corfu, he rhapsodized about The Odyssey and imagined himself in Greek times. Landing in Egypt, he studied the fellahin with an anthropologist’s eye for detail, but a dilettante’s inability to care for much beyond the surface. He was much more at home discussing natural history, writing with an expert’s command of the details of wildlife and environmental conditions. Egypt was strange and exotic and practically overwhelming in its infinity of new sights and sounds. Reading his memoir, I was struck by the way passages relating awestruck wonderment contrast forcefully with vigorous but numbingly routine accounts of endless, bloody hunting. It seemed as though anytime that Rudolf began to ponder the timeless mysteries of Egypt, he pushed aside deeper thoughts to go on yet another hunt. In reviewing his memoir in 1885, English Egyptologist and novelist Amelia B. Edwards noted that the Crown Prince seemed coldly indifferent to the value of life: … it is neither intelligible nor admirable that any man, prince or peasant, should systematically slay every living thing, no matter how common, how harmless, or how abundantly bagged on former occasions. Nor is the slaying the worst part of it. We read again and again of birds and beasts severely wounded, tracked by their blood, and yet escaping to die in lingering agony. All this is told without a word of regret, except for the trophy that is lost. She was hardly the only observer to notice the strange combination of intellectualism and reckless indifference. Willoughby Verner, the ornithologist, recalled that two years earlier, in 1879, he had met the Crown Prince as Rudolf passed through Gibraltar on the Miramar. Rudolf had struck up a conversation about ornithology, his pet subject, and quickly befriended Verner. The yacht, Verner recalled, was stacked with cages filled with trapped animals, and even more skinned or stuffed ones. Verner approvingly cited Rudolf’s tales of killing adult bird to steal their chicks, and of other monstrosities visited on animals. Verner himself preferred to eat what he killed, but displaying it was the next best thing. At one point, near Cadiz, Verner suggested that he and the prince jump overboard to swim in shark-infested waters, which Rudolf eagerly did, to the horror of his government minders, who chased after them with armed gunmen at the ready to secure the prince’s return. Rudolf considered the whole thing a “capital joke,” but Rudolf’s thrill-seeking and risk-taking had become problematic for the Empire. Verner said that one of the minders had confessed to him that Rudolf had forgotten “the immense value his life was to the empire.” In Egypt, Rudolf’s body count was shockingly large, and hundreds of pages of his two-volume memoir detail every animal he killed in painful detail. In this, he was hardly different from the other royal hunters, who would fell whole zoos’ worth of animals in staged hunts. The only real difference is that Rudolf preferred to kill in the wild rather than have animals provided for the kill. Early on in his sojourn in Egypt, he details the elaborate preparations for a hunt and the “melancholy discovery” that farmers were attempting a harvest where he wanted to hunt. Numerous labourers—very poor and scantily clad fellaheen, though some of them of most striking appearance— were working under the direction of an overseer robed in long full garments, and wielding a scourge made of thongs of rhinoceros hide. This worthy approached me with much dignity, and made a long speech accompanied with much gesticulation. I made out with some difficulty that he desired that I should leave the ground.

To describe the Pyramids of Ghizeh would be to repeat a task already done over and over again. They belong to the domain of guide-books and the most beaten tracks of travellers. The tombs of dynasties of hoar antiquity have sunk to the level of a Rigi, and the insignificant names of the Western tourist desecrate the venerable stones. A trip to the Egyptian Museum was equally unimpressive. Rudolf dutifully looked at the artifacts, but recommended that readers consult a guidebook instead. One thing caught his attention: some artifacts that did not match the lessons he had absorbed from his readings and challenged his understanding of the division between pagan Antiquity and Christian modernity: “Some Christian mummies from the early days of Christendom interested me very much, as, until I saw them, I had no idea that mummies of this kind existed.” However, once the prince took to the Nile and was freed, temporarily, from the eye of officialdom and the pressures of representing the Monarchy, his attitude changed, and the cruise upstream on the steamer Feruz produced “glorious never-to-be-forgotten days” that ranked among his happiest, surrounded by “the magic charm of a thousand years of ancient civilization.”

When not forced to perform the role of imperial representative (when his whole body would stiffen in artificial formality, as Brugsch noted with a Prussian’s keen approval), Rudolf found himself fascinated less with the buildings of Egypt than with the very idea that there were other cultures that worshiped other gods and had other values different from those of the oppressive Catholicism of Austria. Brugsch wrote that “he revealed his grasp of science in the eagerness with which he listened to my daily discourses on ancient Egyptian history, geography, mythology, architecture, etc. His remarks, which he interposed here and there, were to the point, and comparisons with other branches of the history of the peoples of Antiquity or of modern times showed the expert who was sure of his subject.” Brugsch was flattered that Rudolf let him talk largely uninterrupted. Entertainment was different in those days. Rudolf was quite taken when Brugsch led him into the burial chamber of Seti I, where he showed him the fabulous hieroglyphic inscriptions and translated them for Rudolf. The prince was deeply moved. “The mystic strain which runs through the dogmas of this religion of thousands of ages past is very interesting,” he wrote, “and the gorgeous wealth of description marks these doctrines as belonging to a southern, and especially an Oriental cultus.” After explorations of several more pyramids and a climb to the top of the Great Pyramid, Rudolf left Egypt on March 24 for Palestine, where he caught a fever. His doctors ordered him to return to Austria, and his impending and dreaded wedding to Stephanie of Belgium. After the wedding on May 10, the imperial couple moved into a castle in Prague, and in what was surely a sign of things to come, Rudolf devoted the first months of his marriage not to his wife but to writing about hunting and travel. He sent a handwritten note to Brugsch asking the Egyptologist to come help him write about Egypt. Brugsch accepted, and moved into the imperial residence in Prague where Rudolf and Stephanie had just set up their household only weeks earlier. Rudolf would wander into Brugsch’s bedroom most nights around midnight to smoke cigars and talk until around three in the morning about “science and art, politics and religion.” One can only imagine what Stephanie thought, but it speaks to a man who desperately wanted someone to talk with who wasn’t a government flunky or a secret spy for his father, or a woman. He considered women ornamental, largely because aristocratic women were trained to basically be sentient topiary. These conversations were not merely idle chatter; they were part of a growing resolve on the prince’s part to assert himself into government. After finishing the book, he wrote his father a lengthy memorandum on the problems of the Empire, echoing the problems and issues he discussed with Brugsch, one of the few people in his circle who would not report their conversation back to the imperial palace. The Emperor did nothing with the report, thinking nothing of his son’s opinions. He was the same man who, after reading the opening of one of Rudolf’s books, asked if Rudolf had written it himself. How he found the time to perform official duties, write thousands of pages, spend whole weeks hunting, and also bed a new woman every few days is simply beyond my comprehension. During the period when he wrote his travelogue, Rudolf had descended into an almost an obsession with writing. Every moment not given over to official events was spent in scientific study or in writing, much to the detriment of his new marriage. The pattern would repeat for the remaining years of his life. In his final years, the prince’s staff would complain to journalists that they were asked to work at all hours to help Rudolf edit and prepare his manuscripts for publication, since the “energetic” prince had conceived a mania for his writing that saw him working in the dead of night through the dawn. During the composition of his masterwork, The Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in Word and Picture, the journalist M. Jokai resented being called to an editorial meeting in the dead of winter at 7 A.M., required by Court etiquette to appear in full evening dress. No wonder later writers said Rudolf suffered from exhaustion. Brugsch and Rudolf worked on the book every day for a month, and Brugsch’s essays and notes for Rudolf ended up used verbatim in Rudolf’s book, sometimes for pages at a time, always prefaced as the words of “my friend.” When Rudolf’s book was published late that autumn, he sent Brugsch a copy with a handwritten inscription: “To the faithful guide and teacher in the land of the Pharaohs, the helpful collaborator, in grateful friendship! Rudolf.” It was around this time that Rudolf developed an interest in exploring and debunking the paranormal, and it is tempting to see a connection between his conversations about religion ancient and modern and his growing belief that all spiritualities were equally false. The mentalist Stuart Cumberland gave Rudolf a reading in the 1880s, and he later recalled that Rudolf came across as deeply read but distracted, a dreamer and an artist. An author writing as the Count de Soissons in 1903 speculated that Rudolf’s thoughts “may have been infected with scepticism” by this time in his life. Others were certain he had become an atheist. “I want knowledge,” Rudolf had written in a teenage essay, and his scientific and even occult investigations proved it, even as he indulged in what a British diplomat gently called “success” in the pursuit of female companionship. His grandson said Rudolf had at least 30 illegitimate children. Brugsch was too much of a monarchist—in favor of both the German and Austrian varieties, having married an Austrian woman—to say a bad word about Rudolf, whom he seems to have openly admired, and whose virtues he likely exaggerated. But the portrait he paints is one that allows us to read between the lines, and to see that Rudolf was both brilliant and troubled, using his charm and surprising depth of knowledge to hide what seems like untreated manic depression. It is always dangerous to speculate on a historical figure’s mental health, but the polarizing descriptions of Rudolf—brilliant but unfocused, lethargic but energetic, charming but bitter, self-important but self-destructive—are less the result of bias in the primary sources than the contradictory nature of a young man who needed help that the Victorian world was ill equipped to provide. The seeds of his destruction were all there in embryo even as a very young man. After he turned 30 in January 1888, he began a downward spiral that accentuated all of his worst tendencies, though in my mind the effort to place the blame for this decline on specific external causes misses that long period where his depression and rage had festered before exploding in his last year, and especially his final six months

6 Comments

Americanegro

10/17/2017 01:56:51 pm

"Sentient topiary"! You can has cheezburger! :)

Reply

Hal

10/17/2017 11:35:51 pm

Incredible, brilliant, most important and best blog ever. Nothing, and that means nothing, could possibly be more meaningful and relevant in today's world. Everyone in the world should be required to read this one blog story. All other websites should be taken down and all books burned except for you know who.

Reply

Only Me

10/18/2017 01:44:46 am

You forgot to include a link to your website, Hal. Thanks in advance for sharing it so I can see why you think so little of it in comparison to this one.

Reply

Only Me

10/18/2017 01:50:38 am

Is there a particular reason why the authors chose to portray Rudolf as bad? I'm trying to understand if this is playing to the old "troubled youth leads to bad end" trope or if there's something more.

Reply

10/18/2017 07:02:56 am

Well, he did enter a murder-suicide pact with his mistress, so there's that. As I will discuss in my review, the authors have adopted the views of twentieth century Freudians, largely without criticism or critique, thanks to their reliance on midcentury secondary sources, and they seem to have a rather Manichean view that if the teenage mistress was a deluded innocent, then Rudolf must consequently be the opposite. Good and evil are rarely so clear-cut.

Reply

Only Me

10/18/2017 11:49:46 am

Thanks. I'll certainly keep my eye out for that review. Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed