|

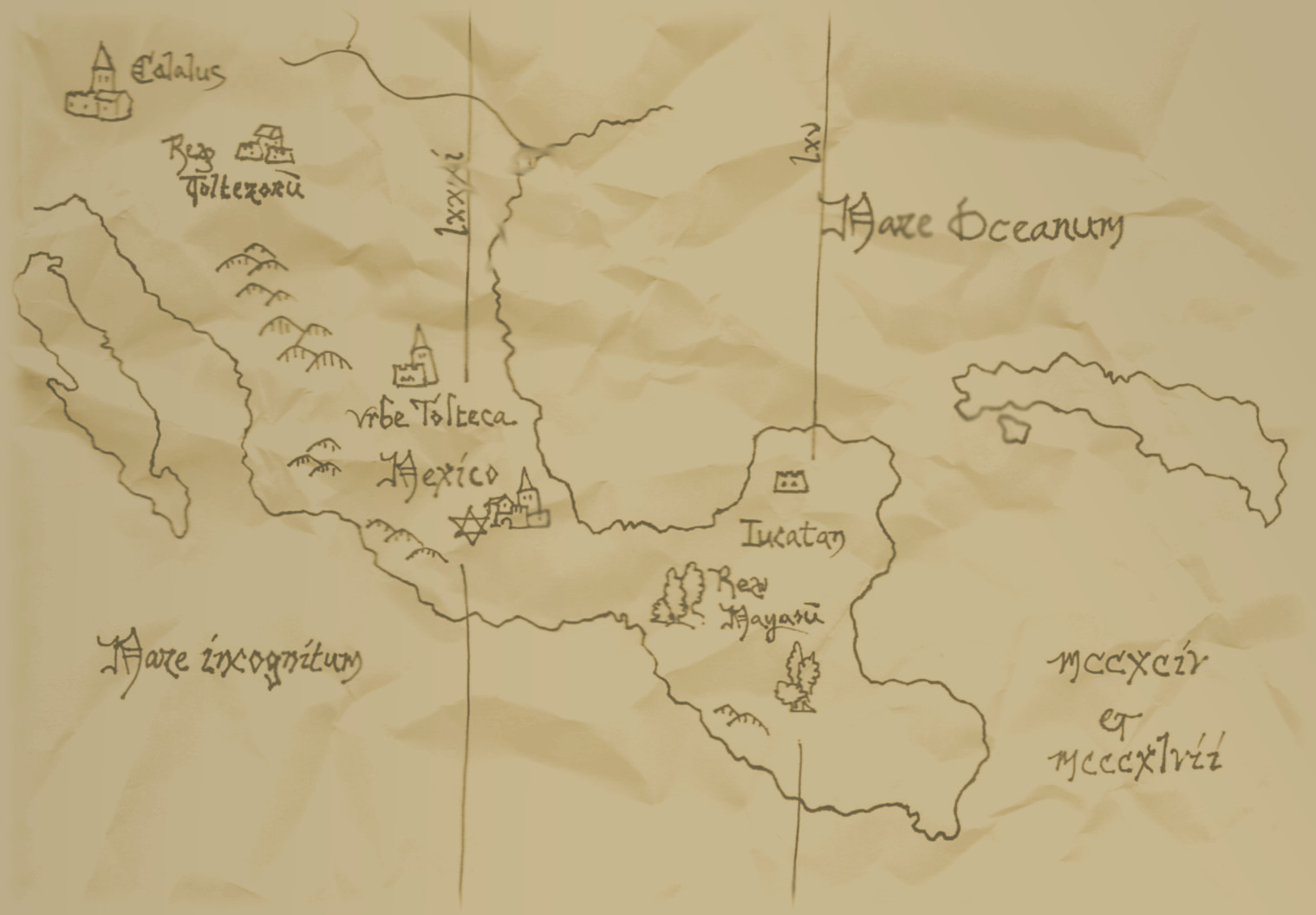

Let me tell you a story. It begins at a used book store, which recently received a consignment of materials from an old man who had traveled widely and collected a number of unusual books. When he died, his kids donated most of them without cracking the spine. After a researcher into the mysteries of the Knights Templar acquired one of these books, he found within a several sheets of paper. They were handwritten notes from the 1980s, detailing research conducted in a private library in Edinburgh. According to the notes, the old man, when younger, had made a copy of an unusual map found in a handwritten journal dating back to the 1500s. That map, in turn, said in a Latin inscription that it was itself a copy of a medieval original composed sometime in the late 1300s. Unfortunately, the owner of the map in Edinburgh refused to allow it to be photographed or photocopied, citing its fragility, nor would he sell the map. Consequently, only this copy is available to review. Templar researchers were excited to discover that it records Templar visits to ancient Mexico in 1294 and 1347, just the times when ancient Mexican sources (Chimalpahin) and Icelandic sagas (Skáholt Annals) claimed that the “Men of the Temple” had traveled to the New World. As I assume you figured out, this map is one I drew in less than ten minutes last night, based on numbers and “facts” taken from Eugène Beauvois’s 1902 article proposing a Templar invasion of Mexico. I also threw in a few intentional errors to ensure no one would mistake it for real. But the fact is that there is no way to distinguish between my fake map and the one that Zena Halpern and Scott Wolter claim is a copy of a copy of copy of an original, especially when combined with an unproveable story that sounds just truthful enough to make the gullible want to believe.

The latest twist, as I understand it, is that there is allegedly a real 1700s map from which the version shown on television this week was allegedly copied. It wouldn’t really make much difference. I thought I’d talk a little about the strangely similar stories that underlie the promulgation of fake (or at least dubious) documents. The closest analogy to the supposed Templar map of Oak Island is the Zeno Map, an infamous hoax from the sixteenth century. The map, which depicts Greenland and some imaginary islands, proved controversial from the start. The only copy of it shown to the public was an admitted fake. The author of the hoax, Nicolò Zeno the Younger, alleged that he had found a medieval map in his family archives, but it was decayed to the point that he had to redraw it himself: “Of these parts of the North it occurred to me to draw out a copy of a navigating chart which I once found that I possessed among the ancient things in our house, which, although it is all rotten and many years old, I have succeeded in doing tolerably well” (folio 47, trans. Fred W. Lucas). The author simply expected us to trust that he had used no modern knowledge of geography, nor any contemporary maps, to fill in the gaps in the rotten chart (the Italian word used implies crumbling decay)—and indeed to accept that such a map existed at all. The accompanying description of the Zeno Brothers’ medieval voyage the author admits to having reconstructed from memory from documents that he had destroyed. This pattern repeats itself time and again in fringe history, where we see this template repeated. Consider, for example, Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon. Smith similarly claimed to have discovered old documents, in this case golden tablets, which no one but him was allowed to see. (He used methods better employed by cartoon characters to keep his friends and enemies from seeing them.) He produced a “translation” of the plates with the help of magic lenses and then asked his followers to accept that the translation represented the unseen originals. The translation, in turn, saw itself scrutinized to tease out hidden details of history. Helena Blavatsky followed this template perfectly as well. Like Smith, she claimed to produce a translation of forbidden documents that uncouth eyes might never see. Hers were ancient texts from a lost civilization, the Stanzas of Dzyan, which she allegedly discovered in a monastery in Asia. Once again, we are asked to accept this on her word, the original documents being unseen in a language unknown. James Churchward duplicated the template as well, making nearly identical claims for his Naacal tablets, which allegedly told the story of Mu. A similar story played out with the so-called Tulli Papyrus, an allegedly ancient Egyptian document that has never been seen in public. The text, supposedly written in hieratic, was allegedly “transcribed” into hieroglyphics because the owner wanted too much money for the original. The “transcription” was then translated into English in 1953 and revealed a UFO encounter in ancient Egypt. The public is asked to accept on faith that the original text really exists, and not that the hieroglyphic transcription was simply back-formed from an English original. So why would anyone trust that unseen originals actually exist, much less change their beliefs about the world as a result? The answer in many cases is an excess of trust, but to a degree there is seeming precedent for the discovery of lost documents in translation. The Emerald Tablet of Hermes claims to be an ancient text, though it is believed to be medieval and Arabic in origin, and it was widely accepted as ancient down to the modern era despite being known only in Arabic and Latin translation. The Book of Enoch was lost for centuries before it was rediscovered in Ethiopia in Ge’ez translation. The difference, of course, is that no one doubted that there once had been an ancient original, and excerpts from a Greek version had long been known from their preservation in the work of George Syncellus. Similarly, the Second Book of Enoch was long known only in Slavonic translation but scholars accept that it is a translation from a lost Greek original. (In 2009 Coptic fragments were found, helping to confirm that there was an underlying original used for both translations.) We could offer many other examples, but perhaps the closest analog to the discovery of unseen ancient texts in the fringe history tradition is the discovery and loss of an Arabic text of extraordinary influence on both fringe history and the Romantic movement. Murtada ibn al-‘Afif composed a history of Egypt around 1200. In 1584, a copy was made, and somehow every other copy in existence was lost or destroyed. This copy, the last in existence, ended up in France, in the library of Cardinal Mazarin, where in 1665 a French scholar named Pierre Vattier translated it into French. The original was lost, and only the French translation survives. For three centuries after that, no one knew anything about the author (he was only identified in the 1970s), and there was no Arabic original remaining to back up the French (and later English) translation. The book was hugely influential among the Romantic and Gothic authors (Shelley wouldn’t stop reading it until a friend threw it out the window), and it served as a source and justification for the Curse of Tutankhamun, and an inspiration for Lovecraft’s Necronomicon—another book that (fake) legend said survived only in Latin translation from a lost Arabic original. “The Arabic original,” Lovecraft said, “was lost as early as Wormius’ time, as indicated by his prefatory note; and no sight of the Greek copy—which was printed in Italy between 1500 and 1550—has been reported since the burning of a certain Salem man’s library in 1692.” While Murtada’s book offers an astonishingly close parallel to the fabulous lost documents we are asked to accept on faith, there are key differences: Contemporary accounts by others demonstrate that the Arabic text once existed, but even if we lacked that, the translation that Pierre Vattier produced contained details and stories that were unknown to Europe in his day, but which exactly match (often verbatim) stories from other Arabic texts such as the Khitat of al-Maqrizi or the Akhbar al-zaman demonstrate that there was a genuine text Vattier was working with. The more doubtful modern documents lack this kind of context and confirmation—parallel texts, credible witnesses, extant fragments, records of their prior existence, etc. This is not to say that they can’t be authentic, only that they have a much higher burden of proof to overcome since there is nothing to support their claim to legitimacy.

29 Comments

Time Machine

11/19/2016 11:38:31 am

>>. Smith similarly claimed to have discovered old documents<<

Reply

Peter Geuzen

11/19/2016 11:46:37 am

The picture in Wolter's blog is presumably the 1700s variant from Halpern and not a copy of it. The version in the show was clearly a scan or photocopy. It would be easy enough to secure blank paper from the 1700s by ripping the end paper out of a period book. The line weight and bleed could be checked for the type of pen or quill or whatever used, and the ink soak itself could be chemically tested. The ink is the hardest thing to fake, and as a result I believe is what has been used to prove other maps as fakes. Nonetheless maybe results of ink testing are non conclusive. Otherwise, pretty much looks like a fake for all the other reasons you clearly note.

Reply

11/19/2016 01:07:23 pm

It might be similar to the case of the Vinland Map, which many have argued began as a genuine mappa mundi to which Vinland was later added by a hoaxer. On the other hand, there really isn't anything on this Oak Island map that is really impossible for the late 1700s (save, perhaps, the accuracy of the longitude), so I'm not sure what it would prove in the first place.

Reply

Peter Geuzen

11/19/2016 01:30:05 pm

If its 1700s paper and 1700s ink proven by legit tests, then exactly what you've said is partly what Halpern/Wolter will argue. If they convince the gullible that it's a 1700s thing (even if made up) then they are at least part way down the road to 1179, while also trying to counter argue the longitude point and anything else like hooked Xs. It's somewhat like a forged painting; find an old canvas and use old paint and fabricate provenance, except in this case it's a copy, not an original that represents the forgery which makes it that much harder to prove, especially with the mistakes like the longitude. They only need some people to be fooled to further their cause, not everybody.

Only Me

11/19/2016 12:54:18 pm

"...we are asked to accept on faith..."

Reply

Time Machine

11/19/2016 01:44:36 pm

"Faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen"

Reply

Kathleen

11/19/2016 02:50:54 pm

I find myself agreeing with the quote of TM. (!)

Tom

11/19/2016 01:03:46 pm

Here is a point for the fringe to consider, the Catholic Church had established representatives (up to the level of Bishop) in both Greenland and Iceland well before 1179 so any maps dating to 1179 might well have been prepared those representatives of the church for local mainland trading purposes and the Templars merely obtained a copy from English or Scandinavian traders

Reply

David Bradbury

11/19/2016 02:24:56 pm

Yes of course. Fitting a fake into a real historical background is a key part of the process.

Reply

John

11/19/2016 01:47:22 pm

The real truth about all history of mankind is that we are eternally doomed to untruth.

Reply

Time Machine

11/19/2016 02:04:07 pm

>>we are eternally doomed to untruth<<

Reply

John

11/19/2016 02:28:44 pm

Time Machine,

Not the Comte de Saint Germain

11/19/2016 02:44:35 pm

All these forgeries and possible forgeries remind me of the Mar Saba letter, which is supposedly an early modern copy of a previously unknown letter by Clement of Alexandria, discovered in the 1970s by Morton Smith. It is very possible that Smith actually forged the letter himself, although we can't be sure.

Reply

Time Machine

11/19/2016 03:20:57 pm

Morton Smith was a homosexual and the letter implies Jesus Christ's teaching of the Kingdom of God was associated with homosexuality.

Reply

Time Machine

11/19/2016 03:42:07 pm

Morton Smith claimed he found the Mar Saba Letter in 1958

Time Machine

11/19/2016 03:49:51 pm

http://www.jesusgranskad.se/strobel2.htm

Dan

11/19/2016 08:50:28 pm

Jason's map is going to show up in some new fringe book that claims a "discovery" of the Templars in Mexico in like two years.

Reply

Peter Geuzen

11/19/2016 09:21:19 pm

Firstly, I'm not sure if this has been mentioned, not having the time to read all comments or Wolter's filtered blog. If we are looking at 1500ish for semi accurate longitude and since this map 'copy' is 1700s what if Halpern/Wolter simply say someone added longitude (and latitude) in the interim to whatever generation copy this is, and that it was likely not on the original (which of course doesn't exist). Problem solved for them, in their minds. Look for it in her book and in Wolter's arguments.

Reply

Jim

11/19/2016 11:23:05 pm

This might mean a delay in the release of her book. I wonder if any were pre ordered.

Reply

Jim

11/20/2016 12:06:42 pm

1500ish is out, the French never used Paris as a prime meridian until the year 1667 !

Reply

John (the other one)

11/19/2016 09:39:47 pm

I just went to Wolter's blog which is annoying as hell to navigate. That is very clearly an old page from a book. You can even see a hole where some of the binding material went through the paper at one time. The edges are darkened as one would expect in an old book, even 75 years old, there is chipping along non-spine edge because the book was likely made of shitty paper so someone would be fine tearing apart the thing.

Reply

John (the other one)

11/19/2016 09:41:45 pm

2nd look not so sure about that hole.

Reply

Jim

11/19/2016 10:21:42 pm

Check out the various shapes and renditions of the letter D, they are all over the map ! (pun intended)

Jim

11/19/2016 10:41:58 pm

The hooked x seems to be two arcs crossed as opposed to two slashes and the L next to it has a slightly rounded elbow, both seem out of place compared to the other Roman Numerals. But perhaps I am just being nitpicky.

Mike Morgan

11/19/2016 10:36:00 pm

Nice touch on the map, Jason, in keeping with the period theme by incorporating the "Hooked X®" in the dates and Mexico as well as using a starting flourish to get the ink flowing on many of the other letters. Kudos to you. Did you also dig up a quill pen to use?

Reply

Time Machine

11/20/2016 12:33:04 am

>>Eugène Beauvois

Reply

Time Machine

11/20/2016 12:37:05 am

It was Johan Reinhold Forster in 1784 who first identified "Zichmni" in the Zeno narrative with Henry Sinclair

Reply

Jojo

11/21/2016 08:29:08 am

The only "Templars" in Mexico were the Knights of Calatrava and Santiago that lorded over the natives after the time of Cortes. What is interesting is that both Pizarro and Cortes were related descendants of the family of Henry the Navigator who in turn had strong ties to the Comyn family of Scotland. Even all the b.s. you read about Rosslyn Chapel being associated w/ the KT is not true. William Sinclair was, by many accounts a Knight of Santiago. There is a strong identification between Scots nobles of that period and Santiago de Compostela also coincidentally the land of Queen Scota...The name James in Scots nobility is referring to Santiago.

Reply

Bob Jase

11/21/2016 12:51:22 pm

The Necronomicon is hardly a fake - why I have at least six completely different versions of it and all are equally real.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed