|

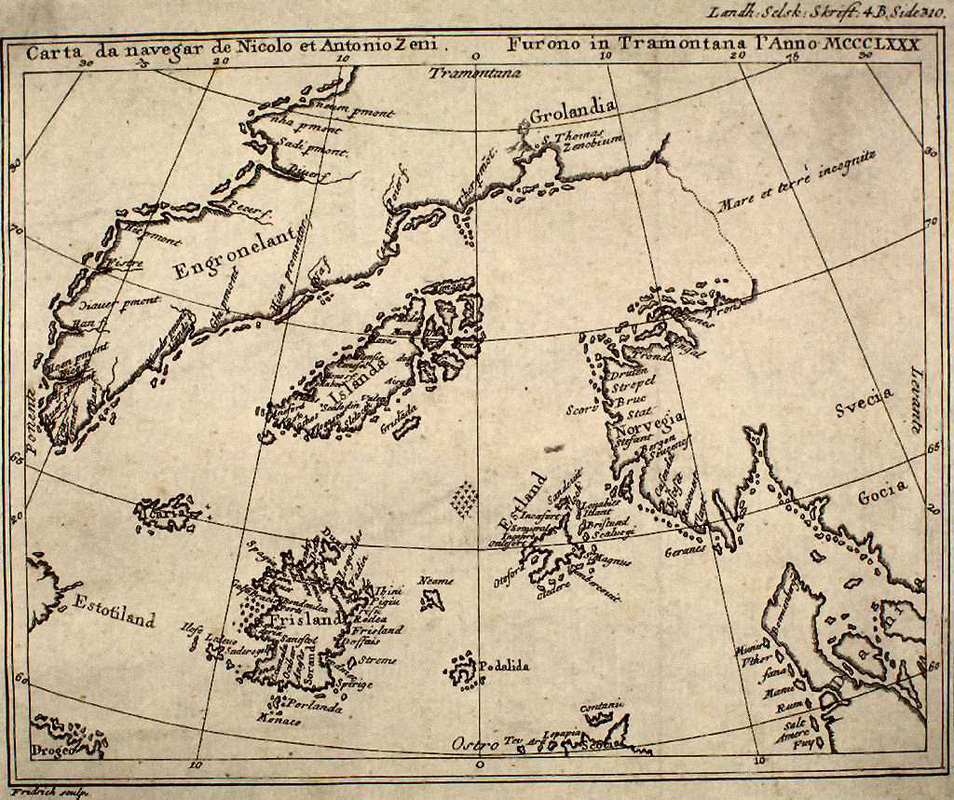

After Europeans realized that Christopher Columbus had discovered new lands, not a new path to Asia, as he had claimed, national jealousies helped inspire a range of claims that other European groups had made the same journey earlier and should be granted pride of place. Many these claims are familiar: Irish monks under Saint Brendan, Welsh explorers under Prince Madoc, and the Norse. The last on that list had the virtue of also being true. In 1558, a Venetian named Nicolò Zeno published a book and an accompanying map claiming that his ancestors, Nicolò and Antonio Zeno, brothers of the naval hero Carlo Zeno, had made voyages of equal importance to Columbus, and a century earlier to boot, earning Venice a place at the pre-Columbian table and a triumph over its rival Genoa, home to Columbus. The book supposedly summarizes the correspondence of the two brothers about their adventures—correspondence which was conveniently destroyed before scholars could examine it when the younger Nicolò Zeno tore the original manuscripts to pieces. Oddly, the book freely mixes supposed quotations from the letters and first person narration by the later author, all cast in the same first-person voice, as though one writer took on three personalities. According to the younger Nicolò’s book, one of the Zeno bothers (also called the Zen or Zeni), Nicolò, sailed to England in 1380 (which is true) and became stranded on an island called Frisland (which is not true), a non-existent North Atlantic island larger than Ireland. In the book, the elder Nicolò claims to have been rescued by Zichmi, a prince of Frisland. Fortunately for him, everyone he meets speaks Latin. Nicolò invites his brother Antonio to join him in Frisland, which he does for fourteen years (Nicolò dying four years in), while Zichmi attacks the fictitious islands of Bres, Talas, Broas, Iscant, Trans, Mimant, and Dambercas well as the Estlanda (Shetland) Islands and Iceland. Later, after Nicolò had died in 1394, an expedition lost for twenty-six years arrives and reports having lived in a strange unknown land filled with ritual cannibals, whom they taught to fish. In fact, rival island groups fought a war in order to gain access to the travelers and learn the art of fishing. Worse, despite being the arctic “they all go naked, and suffer cruelly from the cold, nor have they the sense to clothe themselves with the skins of the animals which they take in hunting.” Antonio Zeno is still there and joins Zichmi on a voyage to the west in search of these strange lands. They encounter a large island called Icharia, whose residents’ speech Zichmi understands. Finally, they travel to Greenland, where Zichmi remains with a colony while Antonio returns to Frisland. On the surface of it, the story seems ridiculous—any survey of the Atlantic admits many of the islands are fakes (though defenders suggest Nicolò the younger misread references to Icelandic settlements as referring to islands since Iceland is called Islande)—but it was one of the most successful hoaxes in the history of exploration. The sixteenth century mapmakers Orelius and Mercator reportedly used it as a source, and Sir Martin Frobisher took it with him on his voyage to the Arctic. One part of the reason for this is that the Zeni were real people, and they really did undertake voyages in the north. There was a foundation on which the younger Nicolò drew in fabricating the story. The other reason for the success is the infamous Zeno Map. Before we look at the map, let’s stipulate the Zeni narrative as presented in 1558 is a hoax. The real Nicolò Zeno (the elder) had been a military governor in Greece from 1390-1392 and was on trial in Venice in 1394 for embezzlement. He lived until at least 1402, despite having “died” in Frisland in 1394. The map seen above was for a long time considered the most important chart made in the 1390s, showing the North Atlantic in stunning accuracy for its day, despite the appearance of several islands that simply do not exist. Of particular note is the accuracy of the shape of Greenland, better than any other fourteenth century chart. Of course, no copy of the map exists prior to its appearance in Nicolò Zeno’s 1558 book. But even from the first, there were several troubling issues. For one thing, the map showed latitude and longitude, something not included on medieval maps. Some dismissed these as a later interpolation. Second, the accuracy of the map varies wildly from land to land. Greenland’s shape is highly accurate, while Iceland’s shape is very much inaccurate. Frisland—which does not exist—has been identified with the Faroe Islands, but only at the cost of sacrificing any claim to the map’s tremendous accuracy, since the two lands look nothing alike. Martin Frobisher, in exploring the Arctic in 1577 in search of the Northwest Passage, relied on the hoax map, and as a result of its mistaken latitudes—listing Greenland’s south tip at 65 degrees instead of 60, he mistook Greenland for Frisland--twice!—in 1577 and again in 1578, and extolled how accurately the map of Frisland matched the coast he reached, which was really Greenland! John Davis, on his subsequent trip to the Arctic in search of the same Northwest Passage, at least recognized that the Zeni map’s Frisland did not match the coast he found, so he claimed to be the discoverer of the new island of Desolation. Sadly, it was again Greenland, which he completely misunderstood because he was using a hoax map to guide him. The island of Desolation, which never existed, was then placed on Hondius’ great chart of the world and the Molyneux Globe. The fictitious passage between Desolation and Greenland was named Frobisher’s Strait, and Henry Hudson though he found it when he sailed up the east coast of Greenland at 63 degrees, believing himself still south of Greenland proper. Also, when Spitzbergen was discovered, it was mistaken for part of Greenland for the same reasons! Modern scholars, having researched the map, concluded that it is derived from a haphazard compilation of earlier charts, including Olaus Magnus’ Carta marina (1539), printed in Venice; Cornelius Anthoniszoon’s Caerte van Oostlant (1543); and derivatives of Claudius Clavus’ early map of the North (c. 1427), including Greenland, which appears nearly identical in shape and orientation on the Clavus-derived 1467 map of Nicolaus Germanus as its counterpart on the Zeno map. Many believe that the younger Nicolò Zeno faked the voyage of his ancestors to help give Venice a prior claim to the discovery of the New World, older than that of Genoese rival Columbus. Some still hold that Zeno merely garbled his ancestors’ real-life voyage to the north, exaggerating or misreporting real events. The weight of evidence is that the Zeno affair is yet another episode in the chronicle of fake history passed off as the real thing.

But here’s the takeaway: How can we be expected to believe, as alternative writers would have it, that Europe possessed secret maps of America and Atlantis dating back a thousand years or more if they couldn’t manage to determine whether Frisland actually existed?

3 Comments

2/20/2013 01:50:22 pm

Zeno wasn't the first to have Greenland swing across the North Atlantic like that. There was a lot of uncertainty about the northern extent of Greenland and of Norway. Several maps show Greenland coming all the way around to connect to Northern Russia with variations of the name Greenland place in two or even three places in the North. I suspect part of the problem was the ice pack. Europeans had a great deal of trouble believing there was no land up there and that sea ice could cover that much space. It was a common belief that sea ice had to spread out from a coast and wouldn't form on open water. It just made sense that there had to be land beyond the ice. Greenland was finally detached from Northern Europe in the late 1550s when the first Westerners rounded Norway, reached the White Sea, and attempted to push on China. The idea of North Polar continent continued to hang on until the middle of the Nineteenth Century.

Reply

Frank Marr

2/28/2014 03:00:34 am

As an indepdendent US pensioner who has read scores of not well-known books across the libraries of the US that verify the Zeno Brothers voyages throughout all the Americas - they're out of print or stolen by Anglo-centric liars.

Reply

Heike Kubasch

7/4/2015 09:48:42 am

I agree with your arguments; however I should point out that Friesland is a province of the Netherlands as well as being an area in Germany. Many of the islands in the North Sea, such as Spiekeroog were originally occupied by the Friesans. So that is origin of the name "Frisland."

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed