|

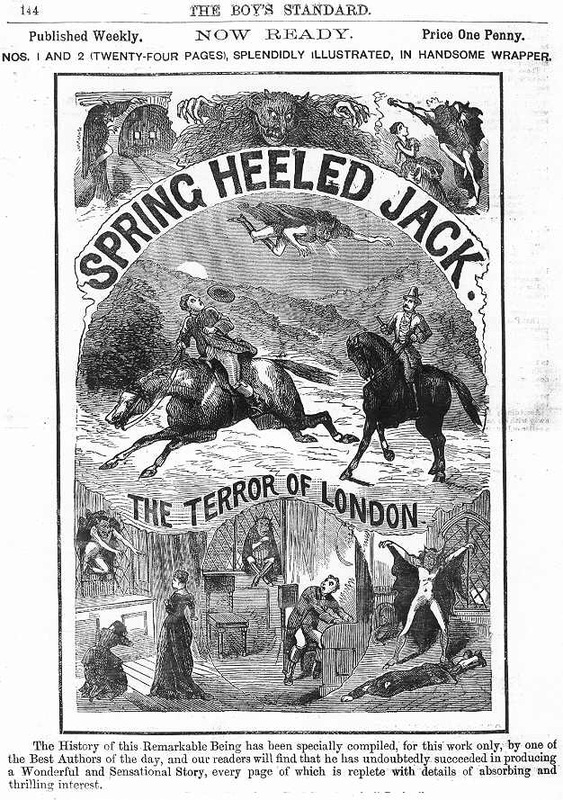

This October, Destiny Books will publish John Matthews’s new book, Spring-Heeled Jack: From Victorian Legend to Steampunk Hero, but the subtitle belies that actual contents of the book, which focus on trying to prove that Jack was actually a modern psychical eruption of ancient mythology, a sort of Freudian return of the repressed in the form of a cri de coeur of liberty and nature against the tyrannical forces of urbanization, industrialization, and centralization. Personally, I think it overreaches. Spring-Heeled Jack was the collective name for a large number of disparate sightings of a terrifying figure variously described as ghostly or diabolical in form who would jump out and scare Londoners from the 1830s down to the 1870s. (The last sighting supposedly happened in 1904.)

Matthews’s book is heavily padded with newspaper articles, which take up much of the text, and consequently there is surprisingly little in terms of analysis for the length of the book. In what analysis there is, Matthews begins to discuss his belief that the legendary terror was a modern eruption of ancient mythology. His discussion is marred with the usual errors of writers not entirely familiar with the Gothic tradition they seek to explicate. For example, he alleges that Charles Dickens invented the use of ghosts in Christmas stories with his Christmas Carol (1843). Dickens was writing in a long tradition of Christmas ghost stories, which began as oral storytelling and by Dickens’ day had seen decades of published Christmas ghosts. Matthews compares the story of Spring-Heeled Jack to Victorian beliefs in ghosts and the supernatural, and he suggests that there is a connection between the character and the popularity of the Jack-in-the-Box, where the Jack was often considered to be a representation of the devil. (Compare the toy’s French name, the “boxed devil.”) Chris Upton had suggested the same thing in writing for the BBC several years ago, and many writers on Jack the Ripper have offered similar thoughts. It is not an unreasonable argument. Less impressively, fringe historian Andrew Collins once proposed that Spring-Heeled Jack, the Jack-in-the-Box, and Jack Frost are all reflexes of a mythical Lord of Misrule named Ak. Matthews doesn’t endorse this theory wholesale (or is even aware of Collins’s claims), but he agrees that the Spring-Heeled Jack is connected to the Lord of Misrule. He notes that Jack appeared in Punch and Judy shows in place of the devil for a time, and Punch was a sanitized form of the Lord of Misrule. This is somewhat debatable; Punch is an Anglicized form of Pulcinella, an Italian stock character of uncertain origin. His connection to the Lord of Misrule is often asserted (as on Wikipedia) but is not universally agreed. The character contains aspects of trickster figures, but to call him a survival of them is a bit like claiming Bugs Bunny is a survival of the ancient Trickster god. Inspired perhaps, but not really a survival in the literal sense. This is also the problem with an additional portion of the writer’s analysis. He goes on to argue that Spring-Heeled Jack is a conglomeration of medieval and antique folklore, including tales of devils and demons, pagan nature deities, and ghosts. He further posits that the widespread use of the name Jack for various fictional figures, from Jack the Giant Killer to Jack Frost to Jack-o’-Lantern (and let’s add Jack Sprat for good measure) is not merely due to the moniker “Jack” being the early modern equivalent of “average Joe” due its ubiquity but rather a deep and mystical connection to ancient myth and legend. By making this claim, he then associates Spring-Heeled Jack with Jack of the Green, better known as the Green Man (though that name was coined in 1939). Here he considers the decorative motif of the vine-covered man found in medieval and modern stonework to be the same as the garland-covered May Day character. So, even though this mythic nature figure is not particularly old in his familiar form—the tradition derives from the May Day festivals of the 1500s and 1600s—Matthews views the Jack of the Green as a direct lineal descendant of pagan nature gods. As such, he makes a quite unsupportable connection between the Celtic and/or Druidic nature deities and Enkidu, the wild man of the Epic of Gilgamesh. He also wrong calls the epic “Sumerian” (it is Akkadian in its standard epic form) and ascribes it to 700 BCE, though it dates back at least a thousand years earlier. There is no connection between Enkidu and Celtic lore that we know of except that both represent the wild aspects of nature. Matthews also falsely alleges that the Green Man figure is tied to the loss of forests that he believes accompanied the building of cathedrals in the Middle Ages due to the amount of scaffolding needed for the construction! According to Matthews, stonemasons carved Green Man figures into churches like Rosslyn Chapel to appease pagan gods whose forests had been destroyed. Good to know that all the farmers who ever leveled a forest are dwarfed by the needs of a single cathedral! Needless to say, this quasi-mystical view of the Green Man, so Victorian in its claims, is not supported by mainstream views. He has a lot more supposed influences on Jack, from Robin Hood to Lucifer to what seems to be Margaret Murray’s imagined witch-cult in Western Europe, but there isn’t really much of a point in continuing on in analyzing Matthews’s claims. He seems unaware that the argument he is making is not factual but polemical: He believes that industrialization cut human beings off from nature, just as city-based governing authorities (secular and religious) curtailed traditional human liberties, and therefore the collective unconscious rebelled against the evils of city life by resurrecting ancient pagan nature gods in quasi-diabolical form. This is an unprovable claim, and one that rests on the ideological claim that industrialization and urbanization are bad and an organic granola country lifestyle is a unique good. It also overreaches in that every cultural expression can be said to reflect, often unconsciously, at some level the culture in which it emerged, but some specific evidence is needed to show that there were direct connections beyond merely existing in its own culture. Here Matthews fails. He has no direct evidence, only comparisons of tropes and types, some of which—if not most—are likely coincidence.

29 Comments

Alaric Shapli

7/31/2016 10:22:32 am

"The character contains aspects of trickster figures, but to call him a survival of them is a bit like claiming Bugs Bunny is a survival of the ancient Trickster god." Heh- many years ago, I wrote a school paper making exactly this claim.

Reply

Denise

7/31/2016 01:25:13 pm

Interesting regarding the deforestation of England. Other than widespread agriculture I have always posited that a percentage of the issue was the need to keep up navel ships to run the empire.

Reply

Weatherwax

7/31/2016 11:38:35 pm

James Burke mentioned in one of the Connections episodes that the British Navy was concerned about the amount of wood glassmakers were using. And of course charcoal production was always a problem. (Most people used charcoal instead of firewood).

Reply

David Bradbury

8/1/2016 03:16:32 am

It wasn't that most people used charcoal instead of firewood- charcoal was produced by a time-consuming and thus quite expensive process. Before the invention of coke, though, charcoal was the best fuel for reaching the temperatures necessary to melt metals.

Denise

7/31/2016 01:30:29 pm

Oh yeah thanks for the info about the prolification on the name Jack used for various supernatural figures/forces. I always wondered if it was a coincidence or some actual connection existed that I couldn't find.

Reply

Zach

7/31/2016 02:38:17 pm

Jason, I might be mistaken, but wasn't it said that spring-heeled jack's attacks were sexual in nature or that they were implied to be? I don't know if John Matthews points this out, but I would assume if that was the case, that spring-heeled jack was always a fictional projection of the suppressed sexual nature of the Victorians and their conservative views.

Reply

7/31/2016 03:25:02 pm

According to Matthews, one of the later accounts seem to describe a rape in which the victim described the attacker as Jack. The first wave of sightings involved no actual crimes. I didn't analyze all the accounts myself, so I can only go by what he said.

Reply

Kal

7/31/2016 03:06:47 pm

The name John is also called Jack.

Reply

Denise

8/1/2016 03:16:59 pm

Jack or Jacques was also the nickname of James. The first "Union Jack " aka the Kong's Colors (not the current flag of the UK) was called that because it created after Scotland and England were united under James V of Scotland after Elizabeth I death. The combination of the cross of St. George and St. Andrew on the flag were credited to this event, and Jack was in reference to James.

Reply

Denise

8/1/2016 03:20:48 pm

I really wish there was an edit function here... I meant the King's Colors.

orang

7/31/2016 05:32:10 pm

how about the Bojack Horseman

Reply

Only Me

7/31/2016 05:39:31 pm

I agree that Matthews seems to have overreached. Since it's been over 110 years since the last alleged sighting of Spring-heeled Jack, I take this to mean he was around for a short time, but didn't have the staying power of other legends.

Reply

TheBigMike

7/31/2016 09:45:48 pm

Frankly I found the Spring-heeled Jack episode of he Fox show Houdini & Doyle to be more plausible than Matthew's assertions.

Reply

Denise

8/1/2016 03:10:20 pm

Yeah the street scenes are waaay too clean. But still fun show.

Reply

David Bradbury

8/1/2016 03:19:36 am

The Amazon page about the book doesn't make it clear how far back before Spring-Heeled Jack the author has gone in the investigation of apparitions. There were quite a few earlier in the 1830s, and the reference point for press reports seems to have been, not any "Jack" but the Cock Lane Ghost of 1762:

Reply

David Bradbury

8/1/2016 08:50:00 am

"Jack of the Green, better known as the Green Man (though that name was coined in 1939)"

Reply

gdave

8/1/2016 12:06:31 pm

Per Wikipedia, "Lady Raglan coined the term "Green Man" in her 1939 article "The Green Man in Church Architecture" in The Folklore Journal."

Reply

8/1/2016 01:55:59 pm

When I read that the term dated to 1939, I checked Frazer's "Golden Bough," which usually has at least a mention of every name, but he only gives "Jack-in-the-Green," "Little Leaf Man," "Green George," and "the May King," so I figured it must be correct.

Reply

Pop Goes the Reason

8/1/2016 02:09:16 pm

The Green Man is a reasonably common pub name in England, mostly it seems in the south. Many of these pubs date back to the early 19th century and some well beyond that.

David Bradbury

8/1/2016 02:22:30 pm

It's complicated. Nathaniel Hawthorne gives the context neatly in "The May-Pole of Merry Mount":

David Bradbury

8/1/2016 02:55:09 pm

Oops- forgot to mention the Green Knight (as in Sir Gawain and...)

gdave

8/2/2016 02:22:53 pm

Clearly the figure Lady Raglan refers to as "The Green Man" pre-dates her article by centuries - but the question is, did she coin the term to refer to this figure?

Reply

gdave

8/2/2016 02:24:12 pm

Sorry - the above was a reply to David Bradbury's reply including a Nathaniel Hawthorne link.

David Bradbury

8/2/2016 03:39:41 pm

Yes, that's why I put "It's complicated". It's actually even more complicated than I thought, because Lady Raglan was using the term "green man" specifically to refer to a type of architectural decoration, and I can well believe that she was the first to do that, regardless of the many earlier uses in other contexts [note how the introductory paragraph of the Wikipedia article begins with the words "A Green Man Sculpture"- it really needs rewriting or retitling because the sculpture-type is not the dominant use of the term].

Zach

8/1/2016 12:10:21 pm

After looking up some more information on Spring-Heeled Jack, I actually came across a couple other sources (outside of his wikipedia entry) that says his earliest appearance was in 1837. Not to get too ahead of myself, but it should be considered how that was the year where Queen Victoria came to power, marking the official beginning of the Victorian period. It would be interesting to find out what other urban legends involving ghostly figures were appearing in England just around that same time. This is just my guess, but if there are any, I bet they would share some key characteristics in their legends, that not only could be similar to Spring-Heeled Jack, but would also reflect the emerging Victorian era beliefs of the time.

Reply

David Bradbury

8/1/2016 02:27:03 pm

As I posted above, there were various manifestations of "ghostly" figures in the 1830s, well before Victoria's accession. Typically they preyed on young women out alone, and one 1836 case illustrates a reason why: a "ghost" which tried to scare two men had three of its ribs broken by them.

Reply

David Bradbury

8/2/2016 03:47:44 pm

Rummaging a bit further, it looks as if there would easily be enough early 19th century ghost scams to fill a substantial book. One from Collingham, Yorkshire, in February 1834, sounds like an early episode of Scooby Doo, complete with cowardly hounds- the "ghost" in that case being a man with a speaking-trumpet, employed to lead the authorities away from poachers.

Reply

Bob Jase

8/1/2016 03:41:22 pm

For a good non-woo book about jack and his ilk see https://www.amazon.com/Spirits-Industrial-Age-Impersonation-Spring-heeled/dp/1499268777/ref=sr_1_12?ie=UTF8&qid=1470080424&sr=8-12&keywords=springheeled+jack

Reply

Alaric Shapli

8/2/2016 07:13:46 pm

Thanks! Got it for my Kindle. Fascinating read- it's particularly interesting to see how a lot of the things that seem so completely weird to us about SHJ as a folkloric figure actually make perfect sense in context.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed