|

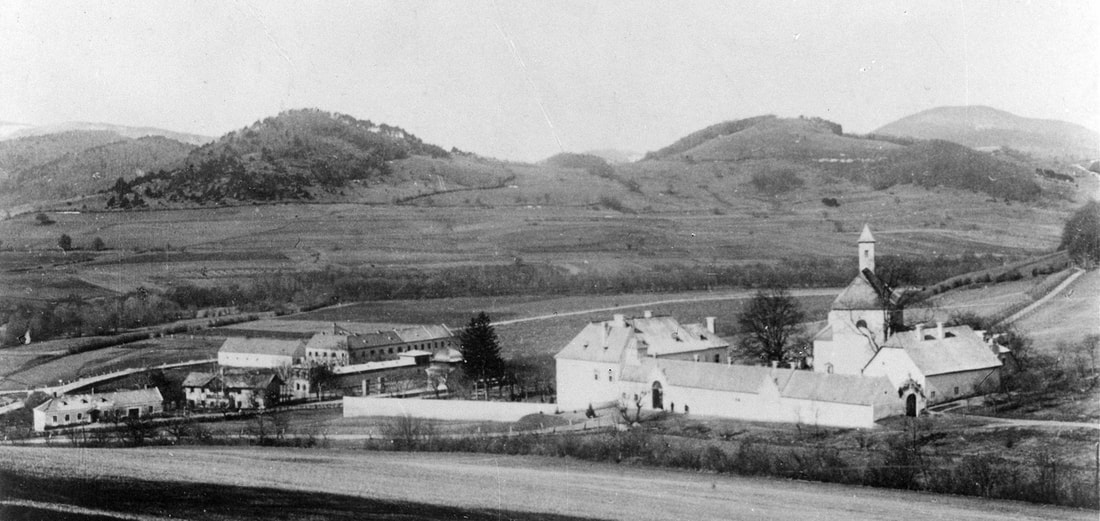

TWILIGHT OF EMPIRE: THE TRAGEDY AT MAYERLING AND THE END OF THE HABSBURGS Greg King and Penny Wilson | 352 pages | St. Martin’s Press | 2017 | ISBN: 9781250083029 | $27.99 On a cold winter’s night at the end of January 1889, the heir to Europe’s most illustrious throne murdered his teenaged mistress, sat for hours with her naked corpse, and then put a bullet through his own head. The shock caused by the death of Crown Prince Rudolf, heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was so great that nearly 130 years later, many still cannot believe that Rudolf would take his own life, despite his repeated and professed desire to do so. Twilight of Empire: The Tragedy at Mayerling and the End of the Habsburgs, the new book by Greg King and Penny Wilson set to be released on November 14, explores Rudolf’s actions at his hunting lodge of Mayerling and reconstructs the end of the young prince’s tragic life. However, the authors ultimately exhume Rudolf’s corpse in a literary reenactment of the infamous Cadaver Synod, in which Pope Stephen VII propped up the rotten bulk of Pope Formosus’s dead body for a parody of a trial. They spin a conspiracy that is logically inconsistent, and driven more by a visceral dislike of Rudolf than a clear-eyed evaluation of facts.

I am both the best and worst person to review this book: the best because few general readers will have read so many of the same sources used as the foundation of this volume to recognize exactly how the authors have combined undigested chunks of ancient speculation at face value, or to have read so much of the history of the Habsburgs; the worst because I don’t share the authors’ loathing of Rudolf. There is irony here, in that I agree with the authors’ admittedly unoriginal conclusion that Rudolf was manic depressive and that his untreated mental illness led to his decline and ultimate demise. But the rest of the story is unsupportable unless you believe depression to be a moral failing that makes a man into a monster. Rudolf was no monster, at least not by comparison with his peers. He did not commit mass genocide like his father-in-law, Leopold II of Belgium. He did not order assassinations or engage in systemic cruelty like the Russian tsars. Nor was he a sadist like his cousin Otto, nor a spousal abuser like his uncle Karl Ludwig. He was neither anti-Semitic like many aristocrats, nor an unreconstructed elitist like nearly all of them. He did not even try to justify his actions in the name of God or ghosts like the crowned heads of Europe. He was, however, like most royals of his era, an unfaithful husband to a wife he was forced to marry against his will, and he was in the end a murderer who entered into a folie à deux with a deluded teenager and killed her, with her blessing, because he was afraid to die alone. Indeed, he had asked friends and family of both sexes to die with him and settled on the uncomfortably young Mary Vetsera, age seventeen, only because all the others had, quite sensibly, said no. I came to Rudolf’s story backward, following much the same path as King, who began with Franz Ferdinand and found himself drawn backward to Rudolf. Around the turn of the century, I read Frederic Morton’s Thunder at Twilight (1989) about the assassination of Franz Ferdinand and became enchanted with the diverse and vibrant panorama of Viennese life. I therefore sought out Morton’s previous book, A Nervous Splendor (1979), about Rudolf. Morton’s novelistic style made the Habsburgs seem human, and at the time, as a young man possessed of teenage angst, I saw some of myself in the doomed prince. Although it has been nearly twenty years since I read most of the books published in English on Rudolf, I remember them well. I haven’t thought much about Rudolf in the intervening years, especially not after I turned 30 and outlived the young prince. It became more difficult to see things from his point of view once I was older than he ever was, but I still remember what it was like to be young. Our authors do not.

To give but one example, after World War I, when Rudolf’s letters were published in a multivolume set (which our authors failed to consult, to their detriment), early reviewers pointed to hypocrisy between Rudolf’s views on Austria and Germany. Rudolf held that Austria-Hungary was an indispensable empire, “because the territory that we occupy cannot vanish.” Yet he staunchly mocked German imperial pretensions, claiming that Germany was nothing but a country united at gunpoint. Vienna’s Arbeiter Zeitung thought this evidence of Rudolf’s inconsistency, but beneath the surface you see the underlying logic: Rudolf opposed Germany because it was a military state; he supported Austrian unity as a federation of peoples in free association. The logic is not about national cohesion but a soft form of liberal democracy, albeit one under the strict guidance of an enlightened monarch. Another example of Rudolf’s “inconsistency” surrounds his private atheism, vocal distrust of the Catholic Church, but dislike of policies or actions that would deprive the common folk of the consolation of religion. This is less an inconsistency than a recognition of the value of faith in making bearable lives that political and economic conditions had rendered, basically, bleak. Our authors don’t spread their gaze much beyond Vienna, but had they done so, they would have found an empire of severely discontented peasants as a result of the uneven distribution of resources and wealth that Rudolf saw and understood needed to change. Once Franz Joseph allowed emigration, these peasants, including my great-grandparents, departed in droves for America, driven out while the aristocrats dined on golden plates. In criticizing Rudolf’s intellect and attempting to cast him as a dilettante masquerading as an intellectual, our authors fail to realize that the criticisms they repeat, often nearly verbatim, from middle twentieth century books, are the result of a particular bias among the authors they base their book upon. I was genuinely surprised to find that they did not read Rudolf’s collected letters, and the mentions they make to imperial archives appear to be, as best I can tell from the end notes, entirely composed of quotations published in other books. Despite my best efforts, I could find no evidence that the authors made use of any material from the Vienna archives not previously published. This is a book that summarizes other books, a literature review masquerading as a dissertation. Part of this seems to be because the authors are not credentialed experts in Austrian history, or the nineteenth century, or Great Power politics; rather, they are self-styled “experts” in “royalty,” working as writers and editors for Majesty Magazine, Royalty Digest, and other aristocratic fetish publications I have never heard of. Here is the one King edits. King has written popular biographies of royals and socially prominent Americans, and Wilson seems to be best known as his coauthor.

I am a friend of the French, and have a deep affection for their country. We are enormously indebted to France as the fountain-head of all the liberal ideals and institutions of our continent, and in every supreme crisis, when great thoughts begin to manifest themselves in acts, she is our example and leader. What is Germany, however, except an overgrown Prussian soldateska and a purely military State? How did Germany utilize the year 1870? Merely to add a Kaiser to her host of petty kings and princelets! She has to pay for a much larger army than before; and visions of unity and empire – fostered and drilled into the people by soldiers, policemen and rigid bureaucrats, and supported by partly spontaneous, partly incalculated patriotism — hover before the points of her bayonets. (trans. in The Living Age, 1922) The fuller quote shows that Rudolf was not merely knee-jerk opposed to Germany but rather opposed the vision of empire it represented, an authoritarian centralization that differed from his own, albeit ephemeral and undeveloped, liberal conception of a federated Austrian commonwealth. This is not to say that Rudolf was a savant. He grossly underestimated Wilhelm II of Germany, for example, and falsely imagined that Otto von Bismarck was conspiring, perhaps with Russia, against Austria. But it shows that he had reasons. This gets to a larger issue: In the middle twentieth century, when most of the books on Rudolf were written and published, the aftermath of the World Wars had made certain political views all but unthinkable. Totalitarianism had given any monarchical rule a bad name, and the collapse of Europe’s empires had given the idea of supranational government a bad name. Our authors live in a world without context, so they fail to understand that the midcentury biographers evaluated Rudolf in the light of their particular political moment. How else to explain our authors sniffing contemptuously at Rudolf’s genuinely prescient insight at the age of fifteen (!) that Europe’s monarchical system was bound to collapse in the next general war unless it could accommodate democratic aspirations? The young Rudolf wrote: Monarchy stands as a mighty ruin, which may remain from today until tomorrow but which will finally disappear altogether. It has stood for centuries and as long as the people could be blindly led as well. Now the end has come. All men are free, and in the next conflict the ruins will come tumbling down. (qtd. In Oscar Mitsi’s 1928 biography) How, precisely, are we to fault Rudolf for actually predicting what really did happen when the long peace broke into the first general war since Napoleonic times and the work begun with the French Revolution finally toppled all of the authoritarian thrones? Rudolf feared this outcome his entire life, and his plans for the future of the Monarchy are strikingly modern. He wanted to see an Austria-Hungary expanded into a federated state, of sorts, with more local control within an imperial framework. His successor, Franz Ferdinand, had much more concrete plans along similar lines, but then Franz Ferdinand knew he was living in the last days of Franz Joseph and needed concrete plans for the future. Our authors see this as inconsistent, that liberal ideals cannot coexist with centralized monarchical government, but that is a failure of modern imagination. It was certainly a possibility in the nineteenth century, which had the example of the federated Holy Roman Empire and its enlightened Habsburg emperors to draw upon. And it is returning today in the supranational federation of the European Union, which has, by fits and starts, tried to establish a stronger centralized executive authority for the same reasons. It is really only the bipolar postwar moment of the Cold War that made the idea of alternative political arrangements look both weak and foolish. Our authors, who have thought less deeply on the subject than Rudolf, fault him for casting about for solutions to problems they will never have to solve. But I have wasted far too much space explaining the authors’ limited view of Rudolf’s politics. More troubling are the authors’ evaluation of Rudolf’s emotions. Here, as in their political analysis, they are largely beholden to middle twentieth century views from books by the likes of Crankshaft, Haslip, Barkeley, Morton, and other names familiar to me. The trouble is that midcentury evaluations were tainted by Freudianism (ironic since Freud lived and worked in Habsburg Vienna) and focused on Freud’s pet obsessions: sex and death. Our authors repeat midcentury judgments uncritically and never challenge the Freudian perspectives of the twentieth century worldview. This leads them to dismiss the majority of Rudolf’s life in a few pages, skipping over his adventures traveling around the world, his prodigious literary output, his efforts to debunk the supernatural, and even giving short shrift to his testy relationship with Wilhelm II. Instead, they posit that his life was a sexually-driven Oedipal psychodrama culminating in a conspiracy. There is no real evidence that Rudolf saw sex as central to his life. He treated sex like a modern rock star on tour—a series of inconsequential affairs used for physical relief and entertainment value, but ultimately little more than a distraction from the real work of life. This is not to justify Rudolf’s hundreds of mistresses or dozens of illegitimate children, or the real pain it caused his wife; it only means that his frequent dalliances were not the focus of his life. If anything, his attitude was like that of Donald Trump, who famously said that when you’re a celebrity you can do anything. “The silly goose thinks I adore her,” Rudolf once said of a mistress, according to the Countess Marie Larisch’s memoir, “and so I can do anything I like with her.” Before last year, that might have seemed terrible. King and Wilson offer a conspiracy theory to explain the suicide at Mayerling. Normally, I would not share the culmination of a book, but since not a whit of it is original, merely a compilation of preexisting conspiracy theories, I spoil nothing by sharing it. It goes like this: Rudolf, in pain from a gonorrhea infection, zonked out on morphine and cocaine, and suffering from a manic episode, conspired with the Hungarian independence movement to use the occasion of a Parliamentary bill in Budapest that would have made German the command language of the joint Austro-Hungarian armed forces to launch a coup against his father that would split the Empire and see the Magyars make Rudolf king. Having rendered his wife sterile by gonorrhea, Rudolf sought an annulment from the Pope so he could marry a Magyar and father a Hungarian dynasty. When the language bill unexpectedly passed, the coup collapsed, and Rudolf told his pregnant mistress Mary Vetsera he had no choice but to follow the Emperor’s demand to break off his affair with her because the Emperor suspected that she was actually his own illegitimate daughter and therefore Rudolf was committing incest with his own sister. After a drunken argument, Rudolf tried to dismiss Mary, who stripped naked and refused to go, prompting him to murder her. Hours later, he killed himself after ordering all evidence of the conspiracy destroyed.

The authors say that this is the most plausible explanation of events, and the one that best fits the facts. It is, quite frankly, ridiculous. However, parts of their analysis are true, and the rest are old rumors. To take the points in order from best established to most speculative: Rudolf’s gonorrhea has been the consensus conclusion since Dr. Albert Wiedmann came to that understanding by studying Rudolf’s medical prescription records half a century ago. Our authors present it as a revelation, but it is not new information. Rudolf’s depression was known even in his lifetime, and suspicions of manic depression surfaced in the 1940s, though John T. Salvendy’s 1988 book Royal Rebel, which psychoanalyzed Rudolf, disputed the claim. Our authors treat their conclusion of “Bipolar I” disorder (their preferred specific diagnosis) as a new discovery, but under the older name of manic depression we find the same claim going back seven decades. Before that, under the name of hereditary madness, Gribble made the same argument of genetic failing in 1914. I have found references to manic activity in accounts by friends and colleagues—his tendency to show up in the middle of the night for hours-long chats, his weeks of round-the-clock writing binges, etc.—but not enough evidence exists to make a conclusive diagnosis. The rumor that Rudolf wrote to the Pope about an annulment dates back to the weeks after Rudolf’s death, but no correspondence to or from the Pope has ever been discovered, so far as I know. Supposedly the Emperor had it destroyed after the Pope forwarded the letter to him. Versions of the rumor are popular enough, and never refuted by the Vatican, that some version might have occurred. The speculation that Franz Joseph suspected Rudolf of incest has nothing to recommend it other than a rumor that the Emperor had a liaison with Mary’s mother Helene Vetsera decades earlier, a rumor that has never been proved and for which no conclusive evidence exists. For the rumor to be true, Franz Joseph would have had to have been involved with Helene in 1870, without anyone noticing, when all of his other dalliances managed to attract obvious attention. Worse, it posits that Franz Joseph thought nothing of his ex-lover sexually pursuing his own son, since Helene was in love with Rudolf and made a grand show of it before pushing her daughter on to him. This conspiracy theory appears in Francis Gribble’s 1914 biography of Franz Joseph, where it is dismissed. But more to the point: Rudolf had spent a year with Mary Vetsera; surely if incest and humiliation were Franz Joseph’s concern, he would have mentioned this earlier and not, as the authors believe, in an argument in public in the imperial box at the Vienna state opera house just before Rudolf’s death. Helene Vetsera would have been in a position to know, and surely she wouldn’t have been so perverse as to purposely arrange for her daughter to have congress with her own brother. To this I will add another minor point: If either Rudolf or Franz Joseph wanted to be rid of Mary Vetsera because she “knew too much,” surely either had the loyalty and assistance of enough military, police, and other flunkies that her death could have been arranged quietly. If dictators today can make unwelcome people “disappear,” surely the Austrian monarchy could have managed the trick. This leads to the next point: That Mary Vetsera was the victim of murder, not a suicide pact. Regardless of the hours between the couple’s deaths, Mary Vetsera was not a murder victim so much as a willing participant in a murder-suicide. She left suicide notes. Murder victims tend not to leave notes about their impending murders. Though forgeries were in circulation in the 1890s, the originals on Rudolf’s Mayerling stationary were uncovered in an Austrian bank vault a few years ago. There is no doubt she planned to die. Finally, we must address the most important of these points: that Rudolf died because of the failure of his coup to seize the Hungarian throne. This is another old story, for Francis Gribble reports it in his 1914 biography of Franz Joseph. It originates from Marie Larisch, Rudolf’s illegitimate cousin, who wrote a 1913 tell-all memoir to seek revenge on the Habsburgs, whom she felt treated her poorly because she had facilitated Rudolf’s affairs. When questioned about her allegation, she sheepishly conceded that “I have no first-hand knowledge of the matter. I only repeat what I was told” by Archduke Johann Salvator, who conveniently died in a boating accident after renouncing his titles and fleeing to South America. On the surface of it, the claim seems to contradict everything Rudolf said he stood for. The man who called Austria-Hungary an indispensable bulwark against Russian and German expansion now wished to break it to bits; the liberal who wanted greater democracy conspired against the liberal government in Budapest; the opponent of nationalism sided with Magyar supremacists; the Habsburg patriot wished to undermine the dynasty. To evaluate the claim would require discussion far more extensive than I care to offer here. Suffice it to say that a conspiracy that would have been widespread enough to stand a chance of succeeding is unlikely to have resulted in no surviving evidence of its existence. It’s true that some in Hungary had proposed making Rudolf a titular king within Austria-Hungary, like the kings of Bavaria within the German Empire, and Rudolf might even have loosely talked of doing so as a way of prompting his father to devolve some political power onto him. However, taking a military command language bill in parliament as the path to coup seems unusual. It is possible, of course, that such a conspiracy existed; but Rudolf might also have merely been working to install a new Hungarian prime minister loyal to him to create a power center for himself within the Dual Monarchy’s ramshackle government. Our authors place much of the weight of conspiracy on one of Rudolf’s four suicide notes, in which he ended a message in Hungarian to a Hungarian friend with a blessing on “our beloved fatherland.” Our authors quote the line differently—“our beloved Hungarian fatherland”—and there is no satisfactory answer for the discrepancy. The shorter version was first published in 1889; the longer in the 1970s. The original exists, but because I have never seen it in facsimile or manuscript—nor, apparently, have the authors—I cannot say which is correct. Our authors take the line to be an acknowledgement that Rudolf was plotting to be king of Hungary, but since Austria-Hungary was a real union of two sovereign states, in which only the Habsburgs themselves held joint citizenship, Rudolf’s phrasing could equally well be a merely conventional acknowledgement of his friend’s nationality. They also suspect that Rudolf shaved his beard to appear more Hungarian, but photos show that he routinely switched among different types of facial hair quite regularly. It is evidence of nothing. But to go on would be an exercise in futility. Our authors are single-mindedly interested in Rudolf’s sexuality, so they don’t engage in any of the literature that looks beyond that, including academic articles that have plumbed intriguing depths, such as the question of whether Rudolf modeled his suicide on that of Ludwig II, a relative and confidant, which if true undermines our authors’ thesis that Rudolf became trapped by his failed coup and acted impetuously. Ultimately, Twilight of Empire is a recycling of old material mostly already present in Gribble’s remarkably frank 1914 book, to which they add nothing but to accept conspiracy theories that Gribble had rejected as improbable. In that respect, their book is not an improvement. (Gribble, though, was a conspiracy theorist of a different kind, thinking the prince murdered.) Structurally, the text is a mess, with a biographical section following multiple retellings of the suicide, lingering on graphic and bloody details, some of which are repeated three or more times. The authors’ analysis—which is really just a summary of rumors current no later than 1914, with a bit of extra sexual prudery, compared to Gribble’s laissez faire attitude toward extramarital imperial sex—is confined to a few pages at the end. The book is neither biography, nor investigation, nor narrative history. It seems to have a muddled purpose. The book’s subtitle, promising that Rudolf’s death foretold the end of the Habsburgs, is a lie. Rudolf’s death created the conditions that led to Franz Ferdinand’s assassination, and it likely encouraged Franz Joseph to stay on the throne long after he might otherwise have abdicated, but the dynasty had dozens of heirs and might have continued on indefinitely if the Great War had not intervened. The Habsburgs are still alive today, though of little consequence. Ultimately Twilight of Empire is the kind of book that should not be written: an unimaginative and unoriginal summarization of better books, produced by remarkably incurious authors who forgo primary sources and original research for the confident certainty that they have solved a great mystery that no other investigator could. It could have been a good book, but like Rudolf’s life, it is but squandered potential that causes us to think wistfully of what might have been.

20 Comments

Only Me

10/24/2017 11:09:31 am

You answered my earlier question about King's and Wilson's motivations. Thanks for the review!

Reply

Faux Schumann

10/24/2017 12:11:06 pm

Personally, I feel a strong connection with Ludwig II of Bavaria, sharing his feelings of living in the wrong times and a love for romanticism.

Reply

Naughtius

10/24/2017 01:42:28 pm

Hi, Jason. Just wondering if you ever read this article or any on the same theme.

Reply

10/24/2017 01:49:26 pm

It wasn't just the Habsburgs. The European royals were all horribly inbred because of their desire for dynastic marriages. The Habsburgs were the worst of them, though, because they steadfastly forbade marriage outside the pool of "equal" families, a pool which inevitably shrank over time. It was Franz Ferdinand's refusal to marry within this pool that indirectly led to the Sarajevo assassination, for he had gone there because, operating as a military officer and not a royal, the governor would treat his wife as an equal, not an inferior.

Reply

Naughtius

10/24/2017 02:26:44 pm

That's interesting, but when you say "indirectly led" do you mean that he would not have went if invited as royalty? 10/24/2017 02:53:21 pm

No, he would have had to as a government official. But the specific arrangements of their parade route, tour, etc. were put in place because he wanted to have his wife there and standing alongside him, instead, as in Vienna, of having to stand behind all the higher-ranking officials.

Mary C Baker

10/24/2017 03:24:11 pm

"posits that Franz Joseph though nothing of his ex-lover sexually pursuing his own son, since" *thought*

Reply

Americanegro

10/24/2017 03:42:26 pm

I fail to see the issue.

Reply

Americanegro

10/25/2017 12:07:47 am

Oh, a typo. I meant I see no issue with a son boning a father's ex-girlfriend. Nor do I think it should be mandatory. And I certainly wouldn't object to the invocation of the Levirate Law.

Reply

Giorgio Tsoukalos

10/25/2017 04:51:12 pm

Seems that Jason can't take any criticism at all! Jason you are a pathetic loser.

Reply

10/25/2017 05:27:35 pm

No, it's just that you're a fake and it can be defamatory to post vulgar material under someone else's identity.

Reply

Weatherwax

10/25/2017 05:57:25 pm

"Once Franz Joseph allowed emigration, these peasants, including my great-grandparents, departed in droves for America"

Reply

dennis nayland-smith

10/29/2017 05:24:48 pm

a violinist of more than one note - one hopes.

Reply

10/28/2017 06:07:28 am

Try to given a good interesting old story. this most famous story. nice post. that is real life story (true Story).

Reply

GEET

10/29/2017 04:39:58 pm

Great review. This made me interested to learn more. I will purchase this book when it's released. Thank you Jason.

Reply

Roxana

12/14/2017 01:49:48 pm

It's really very simple. Rudolf was a troubled young man with poor heredity, worse upbringing and an unhealthy lifestyle. His health had been deteriorating for some years before his death and he had at various times actively sought a companion for suicide. Taking advantage of a besotted teenager was despicable. Even more despicable was the fact he didn't immediately follow her into death. There was no conspiracy, no motive other than his mental and emotional issues.

Reply

1/28/2018 10:01:46 pm

Jason,

Reply

Elxana

2/4/2018 08:47:32 pm

Actually Rudolph was an abusive husband according to Princess Stephanie who describes classic abusive controlling behavior.

Reply

Roxana

2/19/2018 02:27:49 pm

Having read Twilight of Empire for myself I must agree with Jason's judgement though I do not share his respect for Rudolf's supposed abilities, lost princes are always miracles of enlightenment.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an author and researcher focusing on pop culture, science, and history. Bylines: New Republic, Esquire, Slate, etc. There's more about me in the About Jason tab. Newsletters

Enter your email below to subscribe to my newsletter for updates on my latest projects, blog posts, and activities, and subscribe to Culture & Curiosities, my Substack newsletter.

Categories

All

Terms & ConditionsPlease read all applicable terms and conditions before posting a comment on this blog. Posting a comment constitutes your agreement to abide by the terms and conditions linked herein.

Archives

July 2024

|

- Home

- Blog

- Books

-

Articles

-

Newsletter

>

- Television Reviews >

- Book Reviews

- Galleries >

- Videos

-

Collection: Ancient Alien Fraud

>

- Chariots of the Gods at 50

- Secret History of Ancient Astronauts

- Of Atlantis and Aliens

- Aliens and Ancient Texts

- Profiles in Ancient Astronautics >

- Blunders in the Sky

- The Case of the False Quotes

- Alternative Authors' Quote Fraud

- David Childress & the Aliens

- Faking Ancient Art in Uzbekistan

- Intimations of Persecution

- Zecharia Sitchin's World

- Jesus' Alien Ancestors?

- Extraterrestrial Evolution?

- Collection: Skeptic Magazine >

- Collection: Ancient History >

- Collection: The Lovecraft Legacy >

- Collection: UFOs >

- Scholomance: The Devil's School

- Prehistory of Chupacabra

- The Templars, the Holy Grail, & Henry Sinclair

- Magicians of the Gods Review

- The Curse of the Pharaohs

- The Antediluvian Pyramid Myth

- Whitewashing American Prehistory

- James Dean's Cursed Porsche

-

Newsletter

>

-

The Library

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

-

Ancient Texts

>

- Mesopotamian Texts >

-

Egyptian Texts

>

- The Shipwrecked Sailor

- Dream Stela of Thutmose IV

- The Papyrus of Ani

- Classical Accounts of the Pyramids

- Inventory Stela

- Manetho

- Eratosthenes' King List

- The Story of Setna

- Leon of Pella

- Diodorus on Egyptian History

- On Isis and Osiris

- Famine Stela

- Old Egyptian Chronicle

- The Book of Sothis

- Horapollo

- Al-Maqrizi's King List

- Teshub and the Dragon

- Hermetica >

- Hesiod's Theogony

- Periplus of Hanno

- Ctesias' Indica

- Sanchuniathon

- Sima Qian

- Syncellus's Enoch Fragments

- The Book of Enoch

- Slavonic Enoch

- Sepher Yetzirah

- Tacitus' Germania

- De Dea Syria

- Aelian's Various Histories

- Julius Africanus' Chronography

- Eusebius' Chronicle

- Chinese Accounts of Rome

- Ancient Chinese Automaton

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Fragments of Panodorus

- Annianus on the Watchers

- The Watchers and Antediluvian Wisdom

-

Medieval Texts

>

- Medieval Legends of Ancient Egypt >

- The Hunt for Noah's Ark

- Isidore of Seville

- Book of Liang: Fusang

- Agobard on Magonia

- Book of Thousands

- Voyage of Saint Brendan

- Power of Art and of Nature

- Travels of Sir John Mandeville

- Yazidi Revelation and Black Book

- Al-Biruni on the Great Flood

- Voyage of the Zeno Brothers

- The Kensington Runestone (Hoax)

- Islamic Discovery of America

- The Aztec Creation Myth

-

Lost Civilizations

>

-

Atlantis

>

- Plato's Atlantis Dialogues >

- Fragments on Atlantis

- Panchaea: The Other Atlantis

- Eumalos on Atlantis (Hoax)

- Gómara on Atlantis

- Sardinia and Atlantis

- Santorini and Atlantis

- The Mound Builders and Atlantis

- Donnelly's Atlantis

- Atlantis in Morocco

- Atlantis and the Sea Peoples

- W. Scott-Elliot >

- The Lost Atlantis

- Atlantis in Africa

- How I Found Atlantis (Hoax)

- Termier on Atlantis

- The Critias and Minoan Crete

- Rebuttal to Termier

- Further Responses to Termier

- Flinders Petrie on Atlantis

- Amazing New Light (Hoax)

- Lost Cities >

- OOPARTs

- Oronteus Finaeus Antarctica Map

- Caucasians in Panama

- Jefferson's Excavation

- Fictitious Discoveries in America

- Against Diffusionism

- Tunnels Under Peru

- The Parahyba Inscription (Hoax)

- Mound Builders

- Gunung Padang

- Tales of Enchanted Islands

- The 1907 Ancient World Map Hoax

- The 1909 Grand Canyon Hoax

- The Interglacial Period

- Solving Oak Island

-

Atlantis

>

- Religious Conspiracies >

-

Giants in the Earth

>

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

- Fossil Teeth and Bones of Elephants

- Fossil Elephants

- Fossil Bones of Teutobochus

- Fossil Mammoths and Giants

- Giants' Bones Dug Out of the Earth

- Fossils and the Supernatural

- Fossils, Myth, and Pseudo-History

- Man During the Stone Age

- Fossil Bones and Giants

- Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man

- American Elephant Myths

- The Mammoth and the Flood

- Fossils and Myth

- Fossil Origin of the Cyclops

- History of Paleontology

- Fragments on Giants

- Manichaean Book of Giants

- Geoffrey on British Giants

- Alfonso X's Hermetic History of Giants

- Boccaccio and the Fossil 'Giant'

- Book of Howth

- Purchas His Pilgrimage

- Edmond Temple's 1827 Giant Investigation

- The Giants of Sardinia

- Giants and the Sons of God

- The Magnetism of Evil

- Tertiary Giants

- Smithsonian Giant Reports

- Early American Giants

- The Giant of Coahuila

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Giants

- Index of Giants

- Newspaper Accounts of Giants

- Lanier's A Book of Giants

-

Fossil Origins of Myths

>

-

Science and History

>

- Halley on Noah's Comet

- The Newport Tower

- Iron: The Stone from Heaven

- Ararat and the Ark

- Pyramid Facts and Fancies

- Argonauts before Homer

- The Deluge

- Crown Prince Rudolf on the Pyramids

- Old Mythology in New Apparel

- Blavatsky on Dinosaurs

- Teddy Roosevelt on Bigfoot

- Devil Worship in France

- Maspero's Review of Akhbar al-zaman

- The Holy Grail as Lucifer's Crown Jewel

- The Mutinous Sea

- The Rock Wall of Rockwall

- Fabulous Zoology

- The Origins of Talos

- Mexican Mythology

- Chinese Pyramids

- Maqrizi's Names of the Pharaohs

-

Extreme History

>

- Roman Empire Hoax

- American Antiquities

- American Cataclysms

- England, the Remnant of Judah

- Historical Chronology of the Mexicans

- Maspero on the Predynastic Sphinx

- Vestiges of the Mayas

- Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

- Origins of the Egyptian People

- The Secret Doctrine >

- Phoenicians in America

- The Electric Ark

- Traces of European Influence

- Prince Henry Sinclair

- Pyramid Prophecies

- Templars of Ancient Mexico

- Chronology and the "Riddle of the Sphinx"

- The Faith of Ancient Egypt

- Remarkable Discoveries Within the Sphinx (Hoax)

- Spirit of the Hour in Archaeology

- Book of the Damned

- Great Pyramid As Noah's Ark

- Richard Shaver's Proofs

-

Ancient Texts

>

-

Alien Encounters

>

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

- Fortean Society and Columbus

- Inquiry into Shaver and Palmer

- The Skyfort Document

- Whirling Wheels

- Denver Ancient Astronaut Lecture

- Soviet Search for Lemuria

- Visitors from Outer Space

- Unidentified Flying Objects (Abstract)

- "Flying Saucers"? They're a Myth

- UFO Hypothesis Survival Questions

- Air Force Academy UFO Textbook

- The Condon Report on Ancient Astronauts

- Atlantis Discovery Telegrams

- Ancient Astronaut Society Telegram

- Noah's Ark Cables

- The Von Daniken Letter

- CIA Psychic Probe of Ancient Mars

- Scott Wolter Lawsuit

- UFOs in Ancient China

- CIA Report on Noah's Ark

- CIA Noah's Ark Memos

- Congressional Ancient Aliens Testimony

- Ancient Astronaut and Nibiru Email

- Congressional Ancient Mars Hearing

- House UFO Hearing

- Ancient Extraterrestrials >

- A Message from Mars

- Saucer Mystery Solved?

- Orville Wright on UFOs

- Interdimensional Flying Saucers

- Poltergeist UFOs

- Flying Saucers Are Real

- Report on UFOs

-

US Government Ancient Astronaut Files

>

-

The Supernatural

>

- The Devils of Loudun

- Sublime and Beautiful

- Voltaire on Vampires

- Demonology and Witchcraft

- Thaumaturgia

- Bulgarian Vampires

- Religion and Evolution

- Transylvanian Superstitions

- Defining a Zombie

- Dread of the Supernatural

- Vampires

- Werewolves and Vampires and Ghouls

- Science and Fairy Stories

- The Cursed Car

-

Classic Fiction

>

- Lucian's True History

- Some Words with a Mummy

- The Coming Race

- King Solomon's Mines

- An Inhabitant of Carcosa

- The Xipéhuz

- Lot No. 249

- The Novel of the Black Seal

- The Island of Doctor Moreau

- Pharaoh's Curse

- Edison's Conquest of Mars

- The Lost Continent

- Count Magnus

- The Mysterious Stranger

- The Wendigo

- Sredni Vashtar

- The Lost World

- The Red One

- H. P. Lovecraft >

- The Skeptical Poltergeist

- The Corpse on the Grating

- The Second Satellite

- Queen of the Black Coast

- A Martian Odyssey

- Classic Genre Movies

-

Miscellaneous Documents

>

- The Balloon-Hoax

- A Problem in Greek Ethics

- The Migration of Symbols

- The Gospel of Intensity

- De Profundis

- The Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolf

- The Bathtub Hoax

- Crown Prince Rudolf's Letters

- Position of Viking Women

- Employment of Homosexuals

- James Dean's Scrapbook

- James Dean's Love Letters

- The Amazing James Dean Hoax!

- James Dean, The Human Ashtray

- Free Classic Pseudohistory eBooks

-

Ancient Mysteries

>

- About Jason

- Search

© 2010-2024 Jason Colavito. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed